Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 19

30 January, 2019

CASE I: 08-36807 (JPC 4048498).

Signalment: Female, Soft-shelled Turtle (Apalone ferox, formerly Trionyx ferox), Unknown age (adult)

History: Found dead in an aquarium

Gross Pathology: Multifocal hyperkeratotic and raised circumscribed lesions on the skin of ventral neck and ventral body (plastron) were observed on gross examination. The carcass was found in a fair to poor body condition. Liver was enlarged and pale. Intestines had watery grayish green contents. There was accumulation of hard dry excreta in the distal large intestine (coprostasis). Several developing ova were seen in the coelomic cavity. Stomach was empty. No other grossly visible lesion.

Laboratory results: Several tissues were positive for ranavirus by PCR.

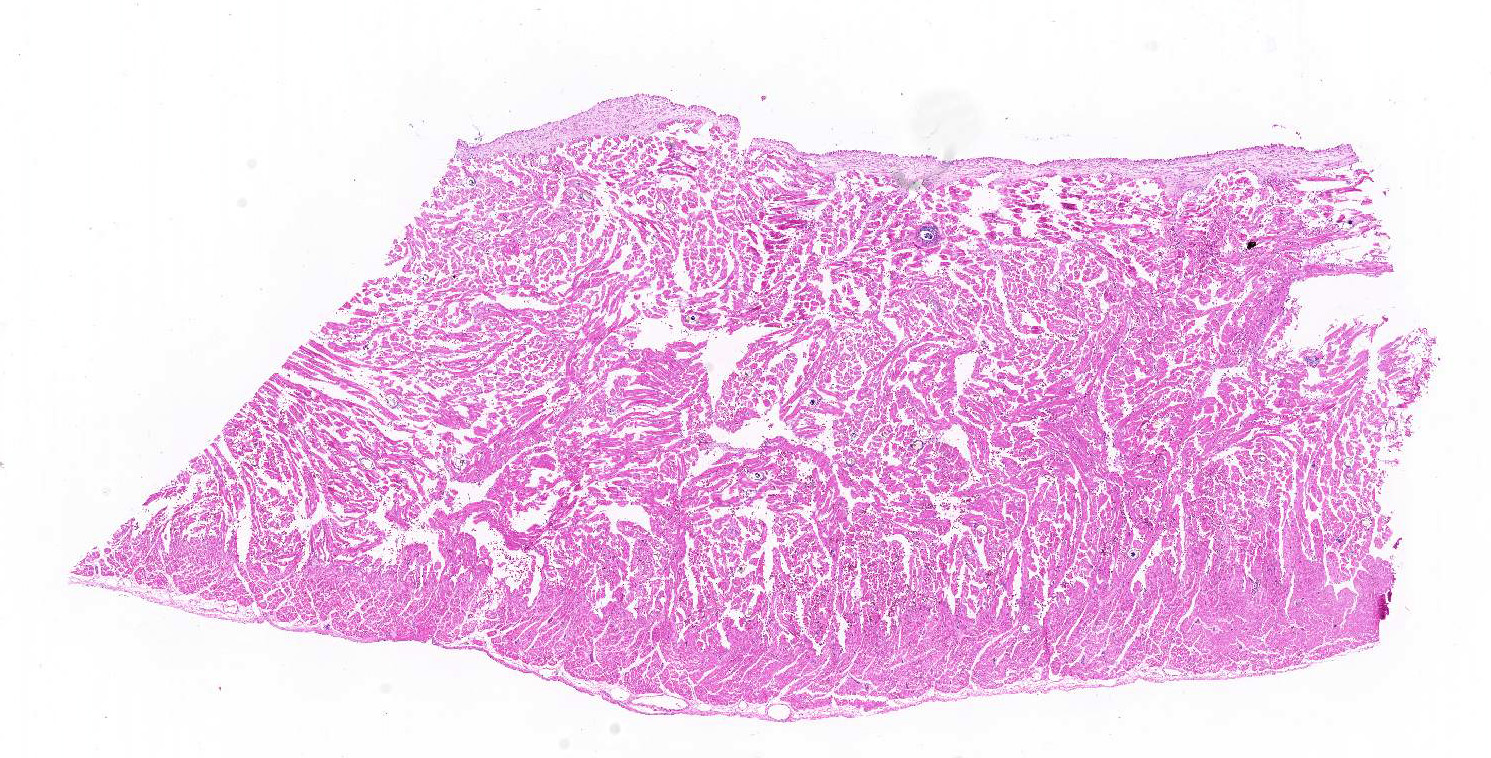

Microscopic Description:

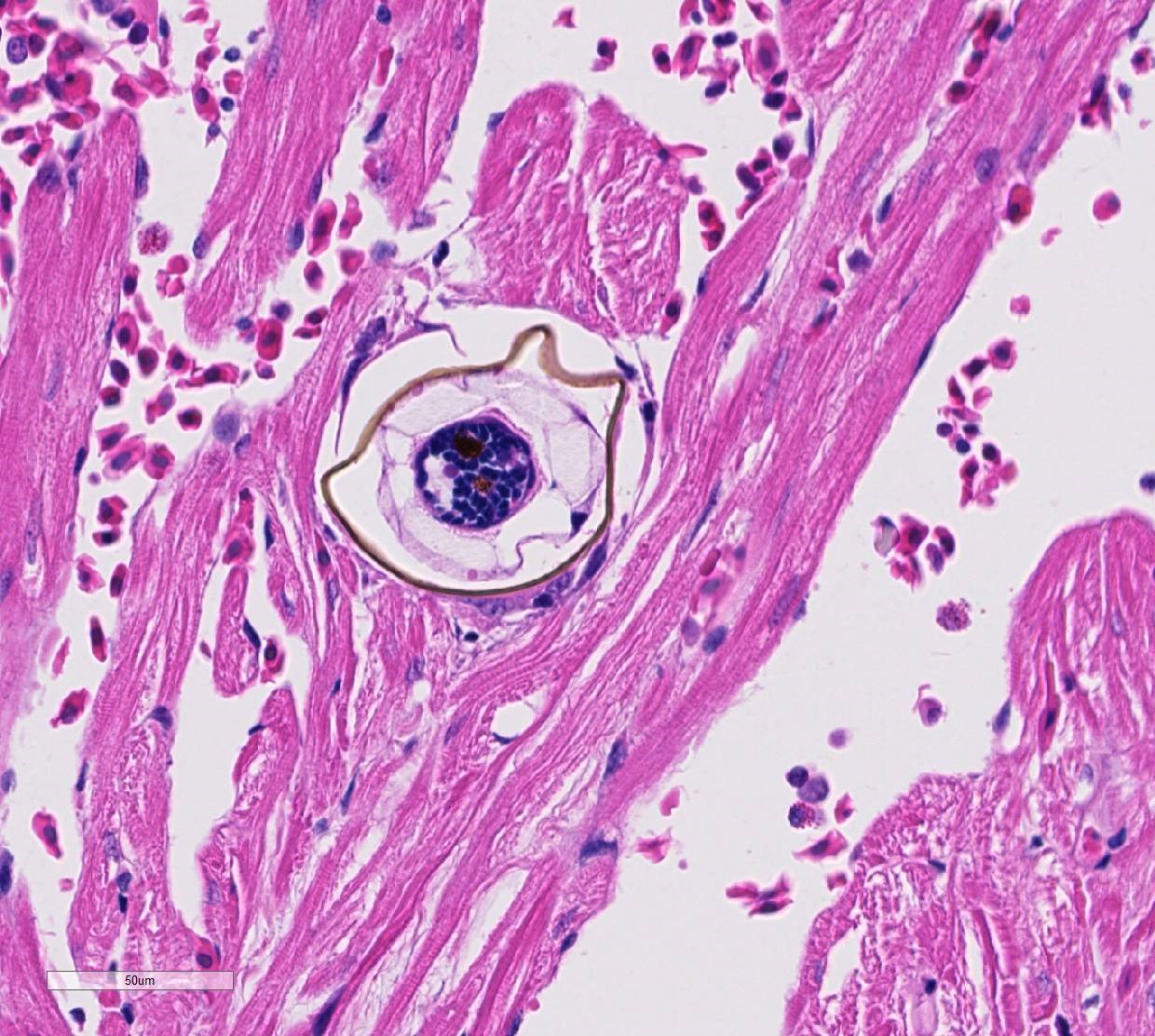

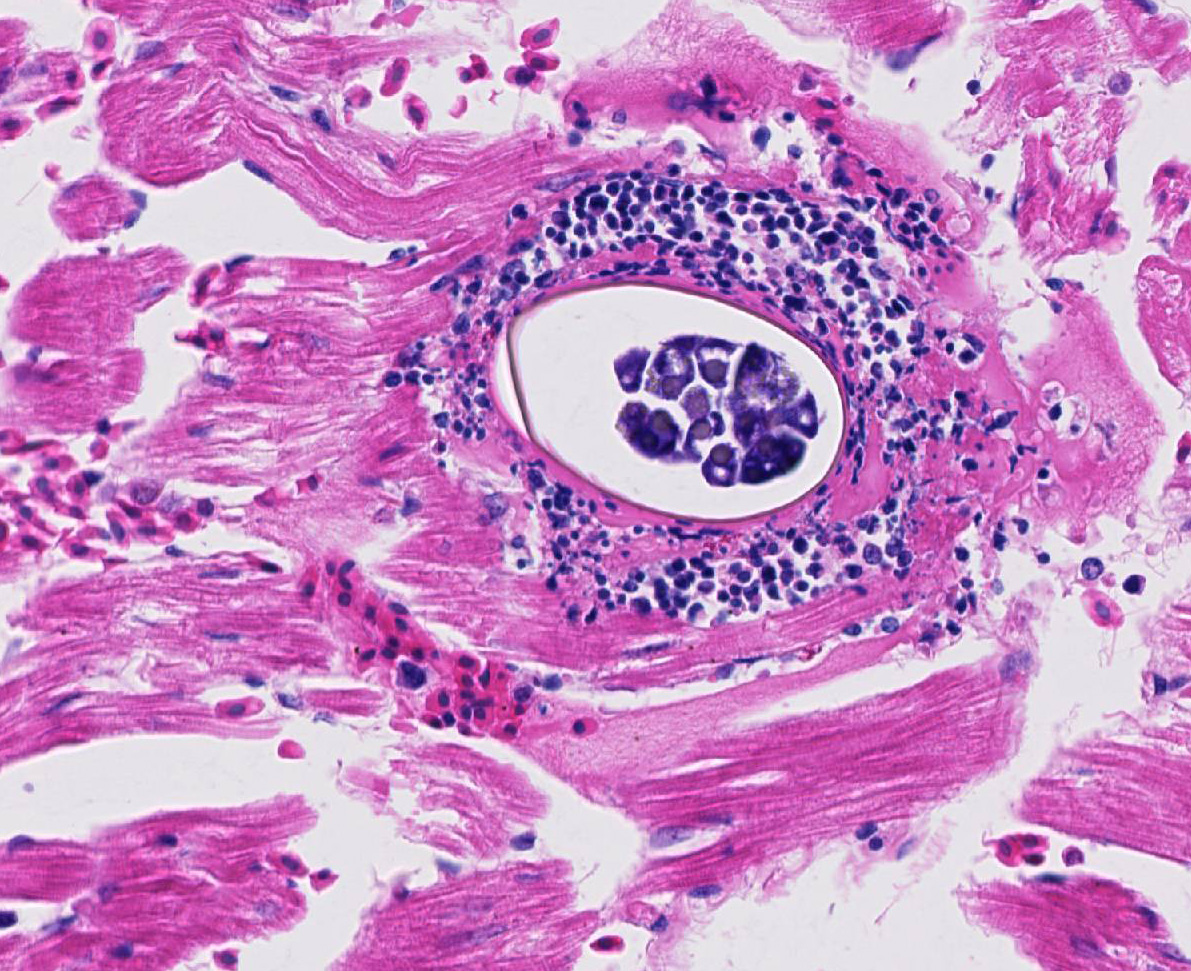

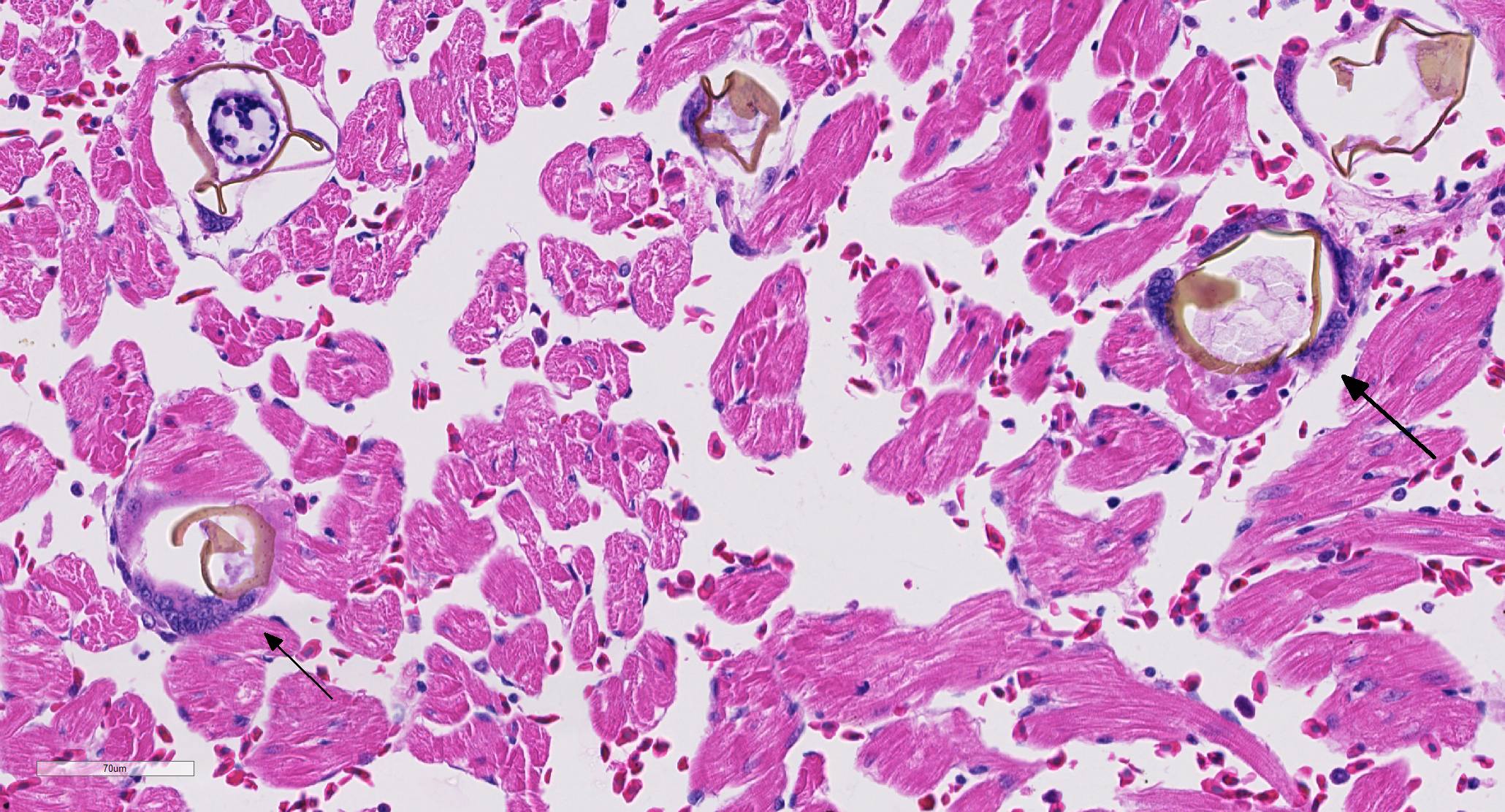

Several myocardial fibers of the sections of heart were disrupted by parasite eggs measuring up to 100x50µm in size. The eggs had 2-3 µm in diameter yellowish refractile often fragmented wall and occasionally contained 2-4 µm in diameter blue round aggregates (miracidium). On the walls of few of these eggs were 5-7 µm in length projecting lateral spines. In some areas, the eggs were surrounded by multinucleated foreign body type giant cells. The eggs were diffusely disseminated in several tissues including the intestines, spleen, liver, kidney and thyroid gland (sections not included). Within vascular lumens in some sections of the heart and liver were about 150 to 300 µm in size adult trematodes. Sections of skin had deep dermal focally extensive areas of necrosis surrounded by moderate amount of collagen fibers occasionally infiltrated by few to several lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. There were no other remarkable lesions.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Heart: Myocarditis, Granulomatous, mild to moderate with trematode eggs and occasional intravascular trematodes consistent with Spirorchid sp.

Granuloma, diffuse moderate to marked disseminated in several organs with trematode eggs and intravascular trematodes (spirorchid), Disseminated Spirorchidiasis.

Contributor’s Comment: Intravascular trematodes (blood flukes) are reported in mammals, birds, reptiles and fish.5 Various species of intravascular spirorchid trematodes, including Learedius learedi, Carettacola hawaiiensis, Hapalotrema dorsopora and H. postorchis are reported in turtles. Specific species identification was not made in the current case. Adult spirorchids inhabit the circulatory system of infected hosts. Eggs may be observed in almost every tissue in the body including the brain, heart, lung, liver, spleen, urinary bladder, shell and slat glands; and may initiate mild to severe granulomatous inflammation. Infected animals may show debilitation, edema of the limbs, and secondary bacterial infections and death. Diagnosis is usually made at necropsy or upon identification of parasites in tissue sections.2 Serology may be useful in evaluating exposure to the infection, although it may not reflect worm burdons.5 Microscopic lesions reported in turtles infected with spirorchids include vasculitis (lymphoplasmacytic endarteritis), thrombosis, perivascular hemorrhage, granulomatous cystitis, enteritis, pneumonitis, hepatitis, meningitis, encephalitis, and cirrhosis.2,4 Remarkable vasculitis was not seen in this case. Coprostasis and poor body condition could be associated to intestinal infection with consequent maldigestion and malabsorption.

Contributing Institution:

The University of Georgia, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathology, Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Laboratory. Tifton, GA 31793, http://www.vet.uga.edu/dlab/tifton/index.php

JPC Diagnosis: Heart, ventricular myocardium: Trematode eggs, intravascular and intrahistiocytic, with mild multifocal cardiomyocyte degeneration.

JPC Comment: The superfamily Schistosomatoidea contains intravascular flukes in three families – Sanguinocolidae, Schistosomatidae, and Spirorchidae.

Schistosomes are grossly visible flukes which cause disease in a wide range of birds and mammals. These parasites have separate genera but the male and female are joined throughout much of their extended life cycle (ranging from 3-30 years). They feed on blood cells and globulins, which are digested in a blind digestive tract with residua regurgitated into the host’s circulation.1 In humans, schistosomiasis (Bilharzia) affects millions of people with up to 200 million on prevention annually.3 The most widespread and pathogenic human schistosomes are S.mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium. S. mansoni and S. japonicum live within mesenteric veins, and their eggs are trapped within intestinal walls, resulting in acute bloody diarrhea, and chronic, hepatosplenic granulomatous disease and fibrosis. The eggs of these two flukes are excreted in the feces. S. haematobium lives within the venous plexi adjacent to the urinary bladder resulting in urinary bladder ulceration and hematuria, and chronically in proliferative and fibrosis lesion of the urinary bladder, and less commonly, ureters. Its eggs are excreted in the urine.1

The family Spirorchiidae, parasites of turtles include 16 recognized genera, and the flukes live within the cardiovascular system. Eggs of these parasites lodge within all organs of the body, forming microgranulomas (as seen in this slide.) The life cycle of spirorchid flukes of freshwater turtles involves a pulmonate snail; that of marine turtles is largely unknown, although a common species of blood fluke, Learedius learedi, has been identified in the limpet Fissurella nodosa.6

Of particular current interest is how the lifecycle of blood flukes is completed at all, without direct access of female flukes to intestinal (or in some cases) urinary bladder. Eggs are laid directly into the bloodstream, and form microgranulomas within tissues. Over the last decade, researchers in the area of human schistosomiasis have begun to unravel the way that flukes and their eggs exploit the immune system to get into the external environment.3 After egg shell components facilitate endothelial adhesion within intestinal vessels, the microgranuloma surrounding the egg actually facilitates the translocation process from intestinal vessels, through the lamina propria and mucosal epithelium and ultimately into the intestinal lumen. The importance of the immune system has been demonstrated by the low fecal egg counts seen in infected immunosuppressed mice; recent research has also focused on the importance of the intestinal microbiome as well. It is likely that a similar process occurs within Spirorchis-infected turtles as well.3

The moderator discussed an upcoming paper (currently in press) which identifies a fatal outbreak of spirorchid parasites in black pond turtles from Thailand.

References:

1. Gryseels, B. Schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2012; 26:383-397.

2. Jacobson, ER. Parasites and parasitic diseases of reptiles. Spirorchiidae In: Jacobson (Edit). Infectious diseases and pathology of reptiles. Color atlas and text. 2007; 583-584. Taylor and Francis CRC press.

3. Schwartz C, Fallon PG. Schistosoma “eggs-iting the host: granuloma formation and egg excretion. Frontiers in Immunol 2018;

4. Wolke RE, Brooks DR, George A. Spirorchidiais in Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta): Pathology. J Wildl Dis 1982; 18 (2): 175-185.

5. Work TM, Balazs GH, Schumacher JL, Amarisa M. Epizootiology of spirorchiid infection in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in Hawaii. J Parasitol 2005; 91(4): 871–876.

6. Yonkers SB, Schneider R, Reavill DR, Archer LL, Childress AL, Wellehan JFX. Coinfection with a novel fibropapilloma-associated herpesvirus and a novel Spirorchis sp. in an eastern box turtle in Florida.