Signalment:

5-month-old, female, mixed-breed dog (

Canis familiaris).This puppy, purchased in Texas, but living in Indiana at presentation, was evaluated for chronic respiratory

distress (present since purchase at 8 weeks of age) and a 2-month history of progressive neurologic dysfunction.

Littermates had responded to antibiotic therapy for

Bordetella infection, but this puppys respiratory condition had

not improved. Serum titers were positive for canine distemper virus. Radiographically, the lungs had a diffuse

interstitial pattern. A cerebral mass was detected in the frontal/parietal lobes by magnetic resonance imaging.

Histologic evaluation of a biopsy specimen of the cerebral mass resulted in a diagnosis of granulomatous amebic

encephalitis. The dog died about 36 hours after the cerebral biopsy procedure and was presented for necropsy

examination.

Gross Description:

Gross lesions were found in the brain and thoracic cavity. A friable, dark-brown to tan, 1.3 cm in

diameter, roughly spherical mass extended from the dorsal aspect of the right frontal lobe of the cerebrum into the

thalamus. The thymus was atrophied. Both lungs were over-expanded, firm, and mottled tan to red-brown.

Indistinct, pale gray to tan, coalescing nodules, 1 to 3 mm in diameter, were evident in cross-section.

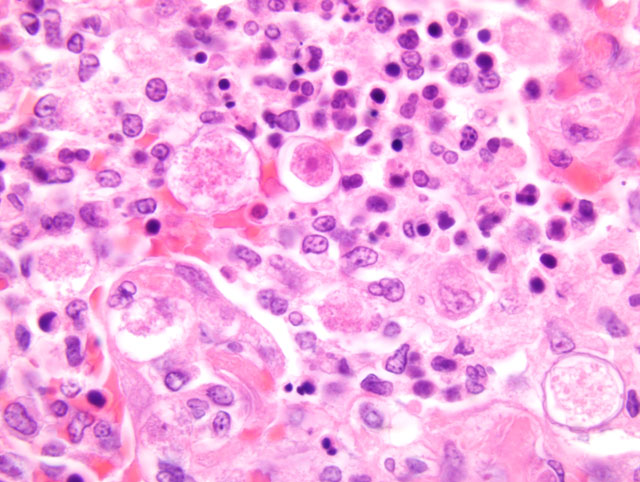

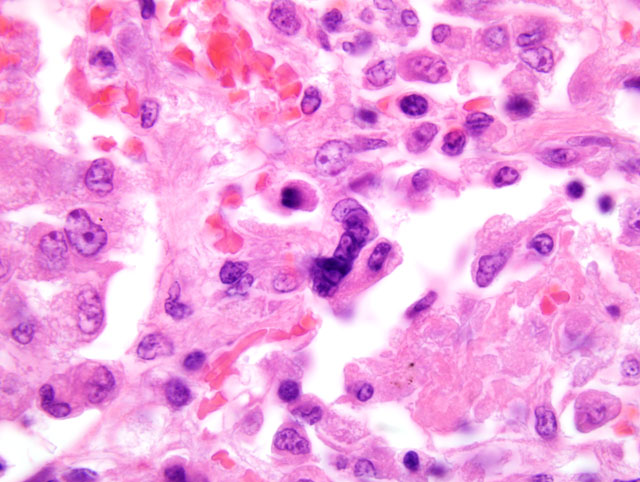

Histopathologic Description:

The submitted sections of lung are representative of the pulmonary lesions.

Individual and coalescing, poorly demarcated nodules (up to 2 mm in diameter) of granulomatous inflammation

were scattered through the pulmonary parenchyma. The centers of the nodules had undergone amorphous to

fibrinoid necrosis with scanty hemorrhage. Alveolar spaces in necrotic (central) and viable peripheral zones of the

nodules were partially filled with neutrophils, macrophages, fibrin, and numerous amoebic trophozoites with fewer

cysts. Trophozoites were spherical to ovoid, ranged from 7 to 19 μm in maximal dimension (mean, 14 μm), and had

a large nucleus with a prominent karyosome and abundant vacuolated cytoplasm. Encysted amoebae had

amphophilic cyst walls, 1-2 μm in thickness, with space between the exocyst and endocyst.

Where granulomatous inflammation extended to the visceral pleura, overlying mesothelial cells were hypertrophied.

Between nodules of granulomatous inflammation, the lung was congested and edematous with increased numbers of

alveolar macrophages. Eosinophilic inclusions were observed in the cytoplasm (and less commonly in the nucleus)

of bronchiolar epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages; these were labeled immunohistochemically with antibody

to canine distemper virus. In other sections (not a feature in the submitted section), sloughed bronchiolar epithelial

cells had large amphophilic intranuclear inclusions that were labeled immunohistochemically with antibody to

canine adenovirus.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Multifocal granulomatous pneumonia with intralesional amebic

trophozoites and cysts.

2. Histiocytic alveolitis with eosinophilic cytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions.

Lab Results:

Frozen lung specimens were submitted to Dr. Visvesvara at the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) for identification of the amoebae. The lung was positive by immunofluorescence and realtime

PCR for

Acanthamoeba spp., and negative by both tests for

Balamuthia mandrillaris and for

Naegleria fowleri.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Escherichia coli were isolated from the lung by bacterial culture. The lung and spleen

were positive by immunofluorescence for canine distemper virus, and negative for canine adenovirus, herpesvirus,

and parvovirus. No virus was isolated from the lung, spleen or brain.

Condition:

Canine distemper; Acanthamoeba sp.

Contributor Comment:

Canine distemper viral infection may have resulted in immunosuppression that

predisposed this puppy to other infections. Acanthamoebiasis was considered the most important of these and the

cause for granulomatous encephalitis and pneumonia. Amoebae were not detected in tissues other than brain and

lung. However, the puppy also had histologic evidence of pulmonary infection with canine adenovirus and oral

candidiasis.

Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and

Naegleria species are the free-living amoebae that have been associated with

encephalitis and disseminated infection in dogs and humans.(2) In histologic sections, recognition of nuclear

features, such as the prominent karyosome and lack of peripheral chromatin, is useful in distinguishing amebic

trophozoites from macrophages. In this case, the presence of cysts in addition to trophozoites in infected tissues

tended to eliminate

Naegleria from the differential diagnosis, but definitive diagnosis of

Acanthamoeba infection

was based on immunofluorescence and PCR results (performed on lung specimens). Some reported canine cases of

acanthamoebiasis have had granulomatous encephalitis and pneumonia (1), and it has been proposed that pulmonary

infection is the result of inhalation or aspiration of the organism from water with hematogenous extension to the

brain. However, amebic encephalitis has also been recognized in a dog with widely disseminated acanthamoebiasis

in which no organisms were detected in the lungs.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Lung: Pneumonia, pyogranulomatous, multifocal, severe, with necrosis and many amebic

trophozoites and few amebic cysts.

2. Lung: Pneumonia, bronchointerstitial, diffuse, moderate, with alveolar histiocytosis, type II pneumocyte

hyperplasia, viral syncytia, and few bronchiolar and histiocytic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic viral inclusion

bodies.

Conference Comment:

Like several others evaluated in recent WSC sessions, this case demonstrates the

importance of searching for an underlying cause of immunosuppression upon the identification of an opportunistic

pathogen. In this case, the extensive pyogranulomatous nodules in the lung were clearly evident to conference

participants as the predominant lesion. Following description of the most striking lesions, the conference moderator

encouraged participants to carefully examine the remainder of the lung; closer examination, beyond cursory

subgross perusal, reveals diffuse bronchointerstitial pneumonia attributed to canine distemper virus infection. Slide

variation is present, and the characteristic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic viral inclusions are rare in

some sections, underscoring the utility of molecular diagnostics (e.g. immunohistochemistry) as employed in this

case. Additional microscopic findings noted by conference participants include multifocal hypertrophy of the

pleural mesothelium, and in some sections, small aggregates of extracellular and intrahistiocytic coccobacilli

(consistent with the bacterial culture results reported by the contributor).

Conference attendees compared and contrasted cases I and II of this conference, and continued the discussion of

pathogenic free-living amoebae, as summarized in the conference comment for case I. This case differs from case I

by the presence of numerous cyst forms, the walls of which are Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive. Additionally,

systemic acanthamoebiasis is associated almost exclusively with immunosuppression, as noted above, whereas

balamuthiasis occurs in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts. Primary amebic encephalitis

caused by

Naegleria fowleri is not associated with immunocompromise. Interestingly,

Acanthamoeba keratitis is a

disease of immunocompetent humans associated with corneal trauma or improper contact lens hygiene, and carries a

far better prognosis than does

Acanthamoeba encephalitis.(3)

We thank Dr. Christopher Gardiner, Consulting Parasitologist for the AFIPs Department of Veterinary Pathology,

for reviewing this case.

References:

1. Bauer RW, Harrison LR, Watson CW, Styer EL, Chapman WL: Isolation of

Acanthamoeba sp. from a

greyhound with pneumonia and granulomatous amebic encephalitis. J Vet Diagn Invest

5:386-391, 1993

2. Dubey JP, Benson JE, Blakely KT, Booton GC, Visvesvara GS: Disseminated

Acanthamoeba sp. infection in a

dog. Vet Parasitol

128:183-187, 2005

3. Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS: Free-living amoebae as opportunistic and non-opportunistic pathogens of humans

and animals. Int J Parasitol

34:1001-1027, 2004