Signalment:

Gross Description:

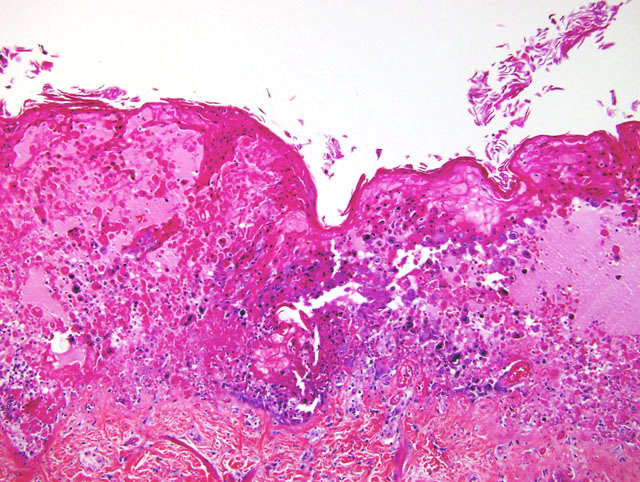

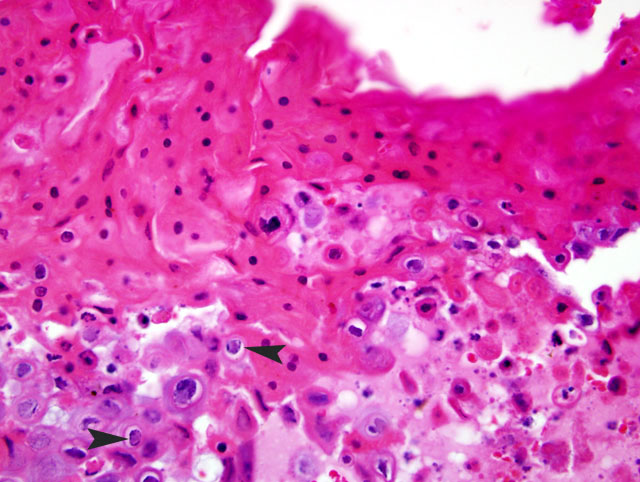

2. Diffuse necroulcerative and hemorrhagic gastroenterocolitis

3. Multifocal splenic, hepatic, and renal necrosis and hemorrhage

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Simian Varicella Virus (SVV) is a naturally occurring herpes virus of Old World Primates characterized by fever, vesicular skin lesions, hemorrhagic ulceration throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and multifocal hemorrhagic necrosis of the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and endocrine organs.4,6 SVV is responsible for sporadic epizootics in biomedical research facilities.1-3,5-8,10 Simian Varicella is antigenically related to Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) in man; the two viruses must be distinguished from one another through PCR (serology from this animal was negative for VZV by PCR and nested PCR). Both SVV and VZV demonstrate a high incidence of asymptomatic or mild disease with seroconversion in immunocompetent animals. A colony survey performed at the WaNPRC demonstrated a 20% incidence of SVV antibodies within M. nemestrina.

The reason for overt clinical disease in these two animals remains unclear. Both VZV and SVV may induce symptomatic disease with immunosuppression; VZV is an important pathogen in man post TBI and chemotherapy. It is hypothesized that the stress of new animal introductions into an established housing room may have precipitated viral shedding in seropositive animal(s). Despite normal blood profiles, the TBI animals may not have been fully immunocompetent, and thus more susceptible to systemic disease.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Natural transmission is primarily through inhalation and/or direct contact with infected skin lesions. The virus is disseminated throughout the body during a transient viremia that clears by day 11 post-infection. SVV DNA has been detected within B and T cells, but not monocytes.4 The virus becomes latent in the neural ganglia, although infectious virus has not yet been recovered from these sites. This could indicate an unknown intermediate stage between acute infection and latency. SVV DNA has been identified in cervical, trigeminal, thoracic and lumbar ganglia, but not in the brain, liver or lung tissues of naturally infected monkeys.4

Clinical signs, which occur 10-15 days following inoculation, usually consist of a skin rash starting in the inguinal area and becoming generalized over the course of 48 hours, developing into macules, papules, and vesicles. Areas of the skin affected include the face, thorax, and abdomen, but not the palms or soles.4 Symptoms begin to subside by day 14 post-infection. Lesions can range from mild and easily overlooked to severe infection resulting in pneumonia, hepatitis, and death. Reactivation following latency may occur spontaneously or in response to immune suppression or stress months to years after the initial infection.4

References:

2. Dueland AN, Martin JR, Devlin ME, Wellish M, Mahalingam R, Cohrs R, Soike KF, Gilden DH: Acute simian varicella infection. Clinical, laboratory, pathologic, and virologic features. Lab Invest 66:762-773, 1992

3. Gard EA, London WT: Clinical history and viral characterization of Delta herpesvirus infection in a Patas monkey colony. In: Viral and Immunological Diseases in Nonhuman Primates, p. 211-212. Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York, NY, 1983

4. Gray WL: Simian varicella: a model for human varicella-zoster virus infections. Rev Med Virol 14:363-81, 2004

5. Mahalingam R, Traina-Dorge V, Wellish M, Smith J, Gilden DH: Naturally acquired simian varicella virus infection in African green monkeys. J Virol 76:8548-8550, 2002

6. Roberts ED, Baskin GB, Soike K, Gibson SV: Pathologic changes of experimental simian varicella (Delta herpesvirus) infection in African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops). Am J Vet Res 45:523-530, 1984.

7. Schmidt NJ, Arvin AM, Martin DP, Gard EA: Serological investigation of an outbreak of simian varicella in Erythrocebus patas monkeys. J Clin Microbiol 18:901-904, 1983

8. Treuting PM, Johnson-Delaney C, Birkebak TA: Diagnostic exercise: vesicular epidermal rash, mucosal ulcerations, and hepatic necrosis in a cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Lab Anim Sci 48:384-386, 1998

9. van Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carstens EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB: Virus taxonomy: the classification and nomenclature of viruses. In: The Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2000

10. Wenner HA, Abel D, Barrick S, Seshumurty P: Clinical and pathogenetic studies of Medical Lake macaque virus infections in cynomolgus monkeys (simian varicella). J Infect Dis 135:611-622, 1977