Signalment:

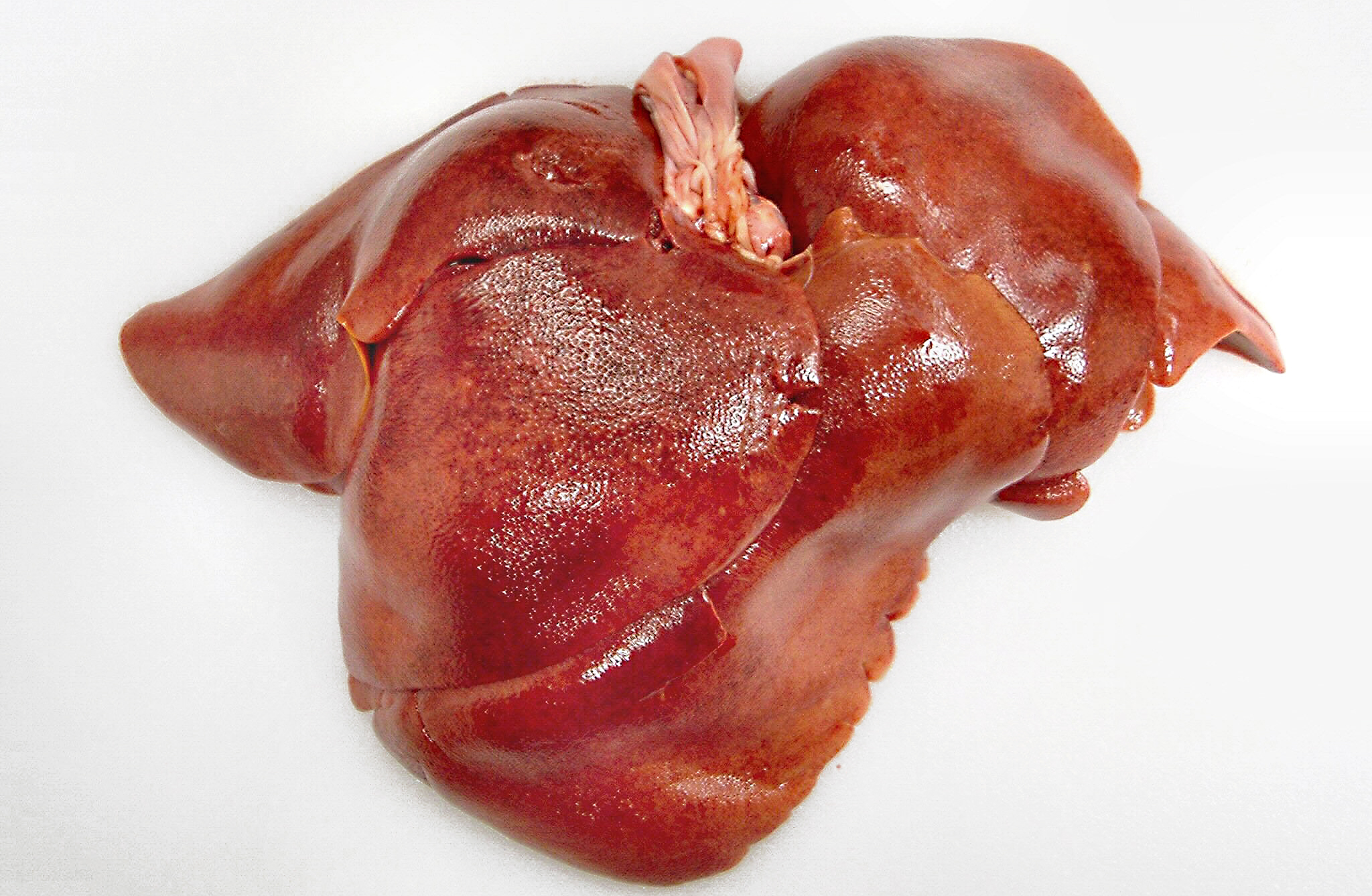

Gross Description:

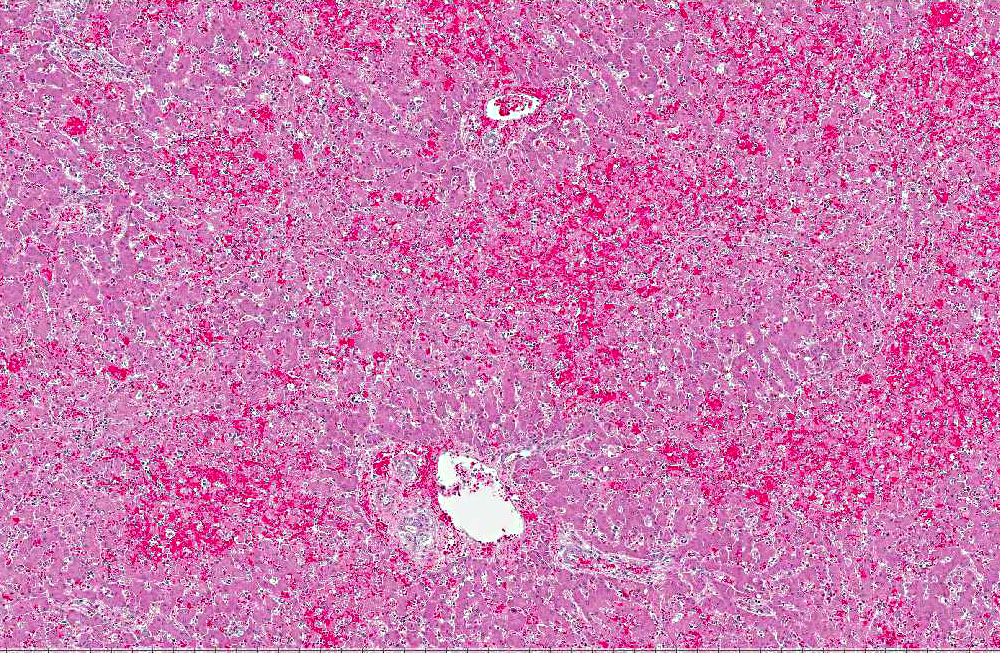

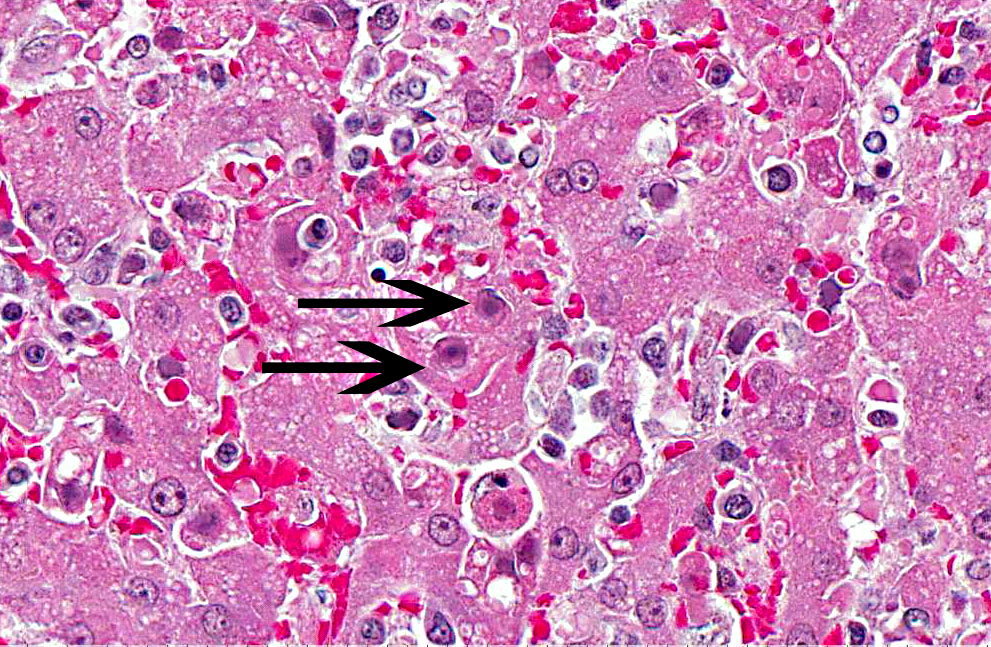

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Infection with CAV-1 in canids can range from subclinical infection to severe clinical infection leading to death.(3,5) In domestic dogs, infectious canine hepatitis is an uncommon clinical disease due to the routine vaccination of domestic dogs. However, there are sporadic individual cases and outbreaks of infectious canine hepatitis in unvaccinated domestic dogs.(1,2,3,5,7) In the wild canid population, subclinical infection with CAV-1 is most likely widespread due to the high incidence of neutralizing antibodies against CAV-1 in this population.(4,6,9)

When a susceptible dog is oronasally exposed to CAV-1, the virus localizes in the tonsils and travels to the regional lymph nodes.(5,8) The virus then traverses the lymphatic system to the thoracic duct where the virus enters the blood. After the dog becomes viremic, CAV-1 is disseminated to the tissues at which point the virus is shed in body secretions. The viremia usually lasts 4 to 8 days postinfection. During viremia, the hepatocytes and the vascular endothelial cells of many tissues are the prime targets for CAV-1 replication. Severe widespread hepatic and vascular damage, which may result in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), often result in death in dogs that do not mount an adequate neutralizing antibody response. Dogs that respond with a high neutralizing antibody response by day 7 postinfection often recover from the disease. Dogs that demonstrate a partial neutralizing antibody response can develop chronic hepatitis. Dogs with a high neutralizing antibody titer before infection can develop mild or inapparent disease. In dogs that do recover from clinical illness with infectious canine hepatitis, the virus localizes in the kidney 10 to 14 days postinfection leading to secretion of the virus in the urine that can last 6 to 9 months.Â

The gross lesions of ICH are consistent with what one would expect considering the cellular tropism of CAV-1. The liver is slightly swollen with sharp edges, turgid, and friable with fine yellow mottling throughout the liver.(8) The gallbladder is often edematous with occasional intramural hemorrhages. There are serosal hemorrhages in the small intestine and stomach. The lymph nodes are enlarged and congested with hemorrhages. The lungs may contain hemorrhages with occasional hemorrhagic pneumonia in the caudal lung lobes. There may be hemorrhage infarcts in the cortices of the kidneys. The brain and the medullary cavity of the long bones may also contain hemorrhages.Â

The microscopic lesions of ICH also coincide with the cells CAV-1 infects. In fatal cases of ICH, the liver is the organ with the predominate lesions. The liver contains centrilobular to midzonal necrosis with dilated sinusoids filled with blood in the areas of necrosis.(8) There can be extension of the necrotic foci from one centrilobular area to another isolating the portal area. There is often a sharp distinction between the foci of necrosis and the normal liver in the periportal areas. The periportal hepatocytes are often normal, but can have increased apoptotic cells or be swollen and vacuolated. The leukocytic infiltrate is mild and surrounds the necrotic focus. The infiltrating leukocytes consist of neutrophils and mononuclear cells. Many of the Kupffer cells throughout the liver are necrotic. Intranuclear inclusion bodies can be seen in the intact hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and macrophages. The microscopic lesions in the other affected organs consist of hemorrhage due to the widespread endothelial damage, which may lead to DIC. Intranuclear inclusion bodies can be seen in the endothelial cells, renal tubular epithelial cells, lymphoid follicles, red pulp of the spleen, and macrophages throughout the body.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Historically, CAV-1 is synonymous with fox encephalitis, described in 1933,(6) and Rubarths disease, described in 1947.(9) CAV-1 can affect dogs, foxes, wolves, coyotes, and bears.(5) Common lesions include hepatitis, anterior uveitis with corneal edema, and interstitial nephritis. Chronic changes seen in animals that survive the initial infection include hepatic fibrosis, interstitial fibrosis, glaucoma, and/or phthisis bulb.(5)

References:

2. Decaro N, Campolo M, Elia G, et al. Infectious canine hepatitis: An old disease reemerging in Italy. Res Vet Sci. 2007;83(2):269-273.

3. Decaro N, Martella V, Buonavoglia C. Canine adenoviruses and herpesvirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2008;38(4):799-814.

4. Gese EM, Schultz RD, Johnson MR, et al. Serological survey for diseases in free-ranging coyotes (Canis latrans) in Yellowstone National Park. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33(1):47-56.

5. Greene CE. Infectious canine hepatitis and canine acidophil cell hepatitis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:42-47.

6. Green RG, Shillinger JE. Epizootic fox encephalitis. IV. The intranuclear inclusions. Am J Hyg. 1933;18:462481.

7. Grinder M, Krausman PR. Morbidity-mortality factors and survival of an urban coyote population in Arizona. J Wildl Dis. 2001;37(2):312-317.

8. Pratelli A, Martella V, Elia G, et al. Severe enteric disease in an animal shelter associated with dual infections by canine adenovirus type 1 and canine coronavirus. J Vet Med B. 2001;48(5):385-392.

9. Rubarth S. An acute virus disease with liver lesion in dogs. (Hepatitis contagiosa canis). Acta path. microbiol. Scand. 1947;69 (Suppl).

10. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed, vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:297-388.

11. Thompson H, OKeeffe AM, Lewis JCJ, et al. Infectious canine hepatitis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 2010;166(4):111-114 .