Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 12, Case 2

Signalment:

10-year-old, male neutered domestic cat, feline (Felis silvester catus).

History:

This animal was referred to the veterinary clinic for weakness and abnormal vocalizations. At the clinical examination, severe paleness of the external mucosae, asthenia and peritoneal blood effusion were detected. Complete blood count and clinical chemistry

showed severe anemia and increased liver enzymes. On ultrasound examination the liver appeared moderately enlarged in size, with a coarse granular texture and slightly rounded margins. Liver biopsies were performed during laparotomy for histological examination.

Gross Pathology:

At laparoscopy, it was referred that the liver appeared enlarged and on the surface there were multifocal dark-red lesions continuously draining blood (consistent with hemorrhages).

Laboratory Results:

Complete blood count revealed many abnormal values, including WBC 19,30 x10^3/ul , Reference Intervals (RI) 5,00-11,00); RBC 4,65 x10^6/ul (RI 5,00-10,00); MCH 17,80 pg (RI 12,50-17,50); MCHC 36,90 g/dl (RI 29,00-36,00); RDW 22,70 % (RI 13,00-17,00); HCT 22,50 % (RI 24,00-45,00); lymphocytes 8,40 % (RI 20,00-55,00); monocytes 5,10 % (RI 1,00-4,00); eosinophils 17,50 % (RI 0,00-12,00); MPV 10,00 fl (RI 12,00-17,00). Clinical chemistry showed creatine kinase 928,50 U/l (RI < 250,00); AST 94 U/l (RI 0 – 57); cholesterol 251,90 mg/dl (RI 56 – 241,00), glucose 34,27 mg/dl (RI 61 – 155,00); BUN 12 mg/dl (RI 13 – 31); iron 76,77 ug/dL (RI 110,00 - 169,00).

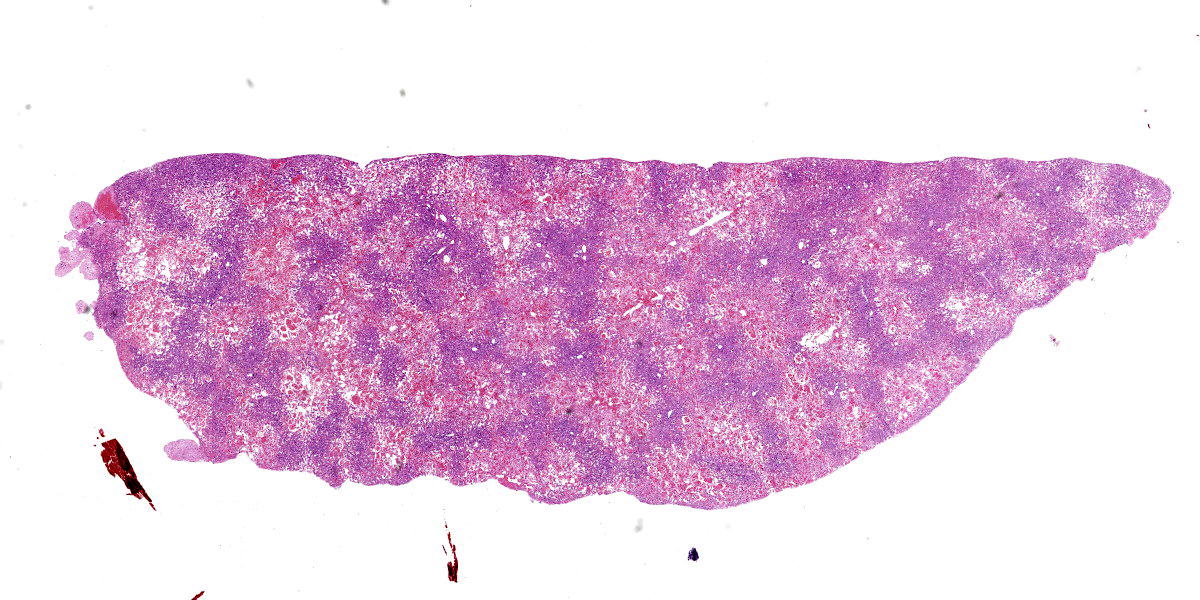

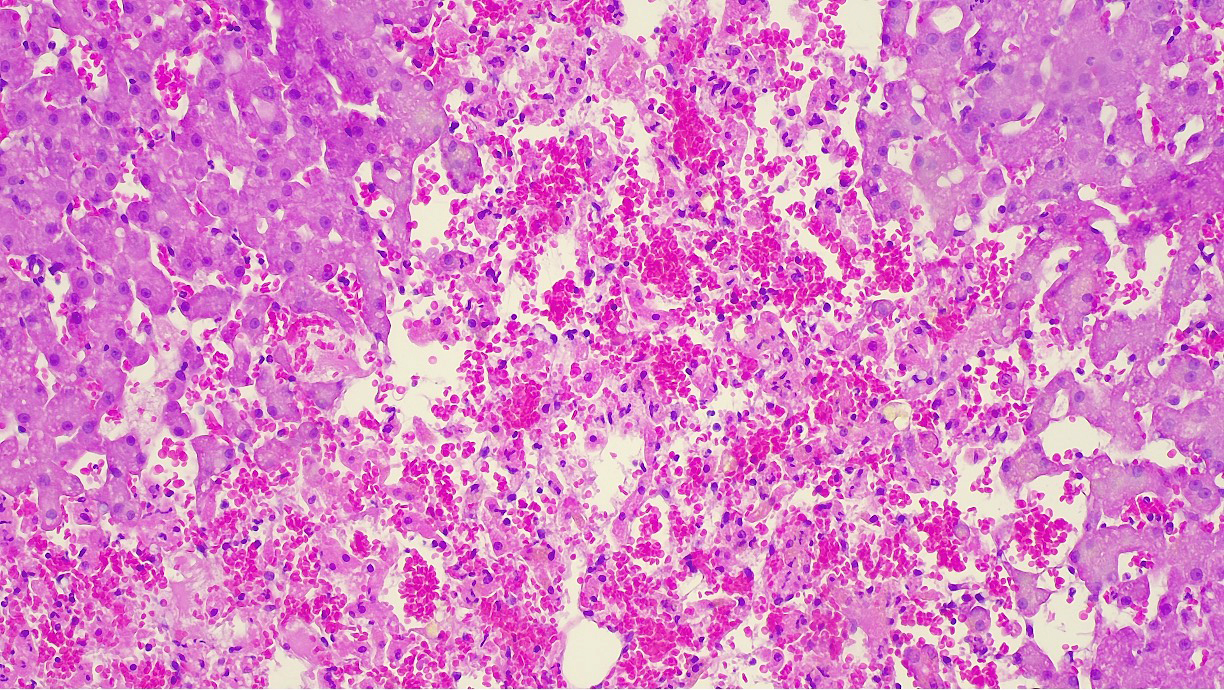

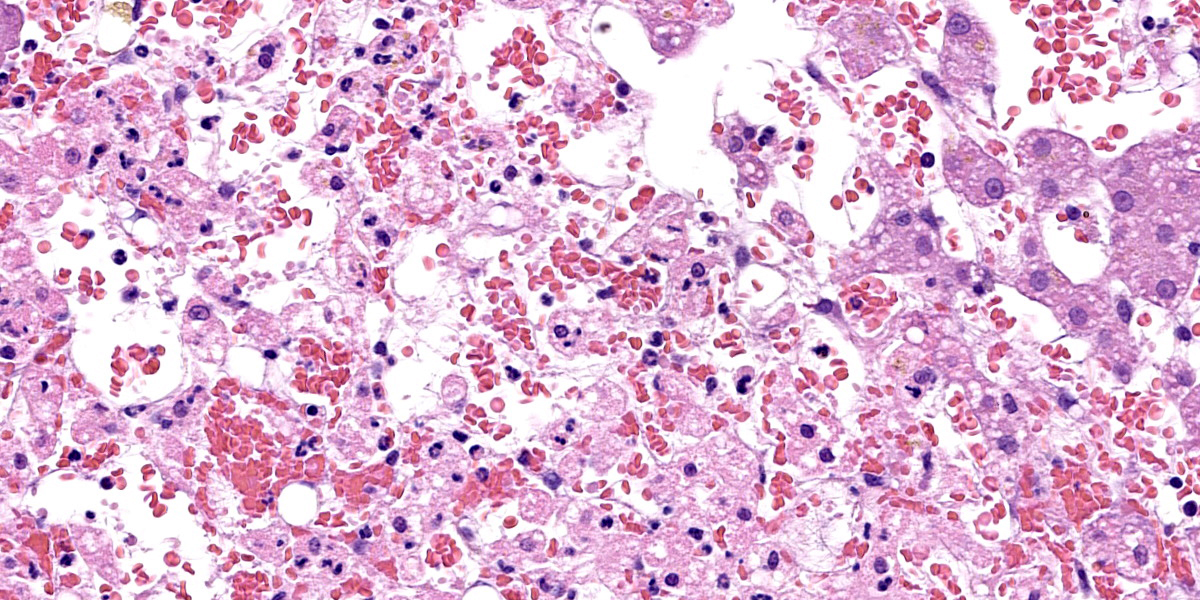

Microscopic Description:

Liver: approximately 70% of the liver parenchyma is affected by multifocal to coalescing areas of moderate to marked sinusoidal dilatation of variable dimensions, irregular in shape and randomly distributed. Occasionally in these areas, loss of endothelial demarcation is evident. Admixed with the dilated sinusoids and lacunae there are extravascular erythrocytes (hemorrhages), meshwork of eosinophilic, amorphous and fibrillar material (fibrin and necrotic debris), few cytoplasmic and nuclear fragments of hepatocytes (hepatocytes necrosis and loss) and rare neutrophils characterized by variable pyknosis, karyolysis and karyorrhexis. In unaffected areas the hepatocellular cords are irregularly distributed and there is loss of lobular architecture. Immediately adjacent to these areas the hepatocytes show mild to moderate atrophy. In the rest of the section, the hepatocyte cords show irregular radial organization and mild thickening (2-3 layers) and hepatocytes are diffusely characterized by large cytoplasm containing mild to moderate amounts of optically empty microvacuoles (vacuolar degeneration with mild steatosis). The hepatocytes show frequent binucleation and occasional mitoses (hyperplasia). Furthermore, multifocally the blood lacunae extend to the subsurface and here the hepatic capsule is covered by a small amount of fibrin mixed with scant extravascular erythrocytes. Small hemorrhages are evident diffusely in the subcapsular-capsular tissue. In addition, multifocally there is a mild hyperplasia of the lining mesothelium which is occasionally is distributed over two layers.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Sinusoidal lacunae (blood-filled), multifocal to coalescing and random, moderate with heptacellular necrosis, loss, and atrophy with multifocal mild fibrinous perihepatitis, hemorrhage, and multifocal mild mesothelial hyperplasia.

Contributor’s Comment:

This case represents an unusual lesion that was not matching any specific entity. One disease that was discussed as possible part of the diagnosis was hepatis peliosis which is what this case was submitted as.

Hepatis peliosis is an uncommon condition of the liver characterized by the presence of numerous blood-filled cystic spaces. These cystic spaces may be lined by endothelial cells (phlebectatic form), therefore indicating sinusoidal dilatation associated also with reticulin alterations.6 Conversely, in the parenchymal form the cystic spaces are formed by necrosis of the hepatocytes and endothelial lining that can therefore be absent multifocally.6 In both cases, grossly, the lesions are characterized by multifocal dark-red areas, variably sized, irregular, and well-circumscribed.6 These lesions are evident on the surface and deeply into the liver tissues, but superficial severe bleeding is usually not described.

In our case, a parenchymal form was considered as more suitable because of the detected necrosis.

Usually, hepatis peliosis is not associated with clinical alterations linked to liver dysfunction, whereas in our case an increase in liver enzymes and anemia were observed. For this reason, a primary necrotizing hepatitis with unusual and marked cystic sinusoidal dilation could not be ruled out as a diagnosis.

Hepatis peliosis has been reported in cattle,11 dogs,8,12 and cats.3 Its pathogenesis is still unknown. In human medicine, this lesion is associated with the intake of some drugs and infections such as Bartonella henselae and B. quintana.1 In humans and lab animals, increases in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been implicated in lesion development.14 In addition, B. henselae infection notably leads to activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) which can induce a pro-angiogenic response in the host via VEGF and IL-8.10 In dogs, hepatis peliosis has been described in one case following diphacinone2 intoxication and in another case with B. henselae infection.9 In cats, this condition is relatively common in elderly subjects (particularly the phlebectatic form) and it seems that there is not a clear association with B. henselae infection.4 In cattle, a specific form of hepatis peliosis has been described in animals poisoned by Pimelea plants.13

In conclusion, this is an unusual case in which both necrosis and marked dilation of blood spaces (hepatis peliosis-like lesions) were detected. No additional analysis for infectious diseases or toxins were conducted for this case.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Comparative Biomedicine and Food Science, Viale

dell’Università 15, 35020, Legnaro (PD), Italy; https://www.bca.unipd.it/

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Sinusoidal dilation and hemorrhage, centrilobular, diffuse, severe, with hepatocellular atrophy and necrosis and multiple subcapsular hematomas.

JPC Comment:

We thank the contributor for submitting this interesting case. Many conference participants weren’t initially sure what to make of the presentation, with the centrilobular to midzonal distribution of the necrosis leading some to consider a toxicant. We agree that hepatis peliosis is a excellent differential for this case; however, under the careful eye (and immense expertise) of Dr. Cullen, we were able to arrive at a slightly different diagnosis however.

As the contributor notes, the diagnosis of hepatis peliosis involves disruption of the reticulin framework. Such changes were notably absent on our reticulin stain. In addition, Masson’s trichrome highlighted centrilobular fibrosis which was suggestive of a more chronic lesion. Moreover, hepatis peliosis changes should reflect a random distribution, whereas the distribution of necrosis in the submitted sections was repeatable and specific in this case. For these reasons, we do not favor the contributor’s diagnosis and prefer a diagnosis of chronic sinusoidal outflow issues (i.e. dilation and congestion).15,16

An important ruleout for centrilobular necrosis is hypertension secondary to chronic passive congestion (right-sided heart failure), veno-occlusive disease, or thrombosis of the vena cava (e.g. Budd-Chiari syndrome).15,16 Though the contributor did not report cardiac lesions in this cat, the hypereosinophilia noted on bloodwork is an interesting (if non-specific) finding that could hint a Dirofilaria infection – heartworm has been described in cats in northern Italy.7 Thrombosis of the vena cava and veno-occlusive disease are both rare in cats.5 Mechanistically, the progression of hepatocyte loss to fibrosis accentuates portal hypertension (and hypoxia) with subsequent atrophy and necrosis of remaining hepatocytes. An interesting ancillary feature of this case was numerous erythrocytes within the space of Disse. Conference participants felt that this likely reflected both endothelial damage and increased sinusoidal pressure. Erythrocyte extravasation may be encountered in cases with and without impairment of venous outflow however.15

Lastly, we briefly discussed the idea of a toxin in this case. There are several features that do not fit with acute intoxication, however. Histologically, atrophy, congestion, and fibrosis are not consistent with a single intoxicating event despite the presence of hepatocyte necrosis. The low AST on this cat’s bloodwork also argues against this. Absent the other clinical data and history in this cat, a chronic intoxication with an acute disruption could present in this manner.

References:

- Ahsan N, Holman MJ, Riley TR et al. Peliosis hepatis due to Bartonella henselae in transplantation: a hemato-hepato-renal syndrome. Transplantation. 1998;65(7):1000-1003.

- Beal MW, Doherty AM, Curcio K. Peliosis hepatis and hemoperitoneum in a dog with diphacinone intoxication. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 2008;18(4):388-392.

- Brown PJ, Henderson JP, Galloway P, O'Dair H, & Wyatt JM. Peliosis hepatis and telangiectasis in 18 cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 1994;35(2):73-77.

- Buchmann AU, Kempf VAJ, Kershaw O, Gruber AD. Peliosis hepatis in cats is not associated with Bartonella henselae infections. Veterinary Pathology. 2010;47(1):163-166.

- Cave TA, Martineau H, Dickie A, Thompson H, Argyle DJ. Idiopathic hepatic veno-occlusive disease causing Budd-Chiari-like syndrome in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2002 Sep;43(9):411-5.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:258-352.

- Grillini M, et al. Evidence of Dirofilaria immitis in Felids in North-Eastern Italy. Pathogens. 2022;11(10):1216.

- Inoue S, Matsunuma N, Ono K, Hayashi T, Takahashi R, Goto N, Fujiwara K. Five cases of canine peliosis hepatis. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi ((The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science). 1988 Apr;50(2):565-7.

- Kitchell BE, Fan TM, Kordick D et al. Peliosis hepatis in a dog infected with Bartonella henselae. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2000;216(4):519-523.

- Kempf VA, Lebiedziejewski M, Alitalo K et al. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in bacillary angiomatosis: evidence for a role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in bacterial infections. Circulation. 2005;111(8):1054-1062.

- Onda H, Kaneda Y, Ito Y, Wakabayashi T. Peliosis hepatis: a specific lesion in the bovine liver. Acta Patholigica Japonica 1982; 32(6), 1053-1058.

- Sapierzy?ski R. Peliosis hepatis-like lesion in a pekingese dog. A case report. Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 2007;10(1):43-46.

- Seawright AA. Phlebectatic peliosis hepatis in Australian cattle. Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 1984;26(3):208-213.

- Wong AK, Alfert M, Castrillon DH et al. Excessive tumor-elaborated VEGF and its neutralization define a lethal paraneoplastic syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(13):7481-7486.

- Kakar S, Kamath PS, Burgart LJ. Sinusoidal dilatation and congestion in liver biopsy: is it always due to venous outflow impairment? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Aug;128(8):901-4.

- Kakar S, Batts KP, Poterucha JJ, Burgart LJ. Histologic changes mimicking biliary disease in liver biopsies with venous outflow impairment. Mod Pathol. 2004 Jul;17(7):874-8.