Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 1

August 23rd, 2017

CASE II: MU1165314 (JPC 4065317).

Signalment: Two and a half-year-old, female, Charolais bovine, (Bos taurus).

History: This cow had a 1 month history of waxing and waning fever, malaise and nasal discharge, with epiphora and bilateral corneal opacity. Clinical signs regressed with dexamethasone treatment. She progressed to sloughing of the skin on the nose, teats, anus, vulva and coronary bands. She was euthanized due to quality of life issues. There was no history of contact with sheep.

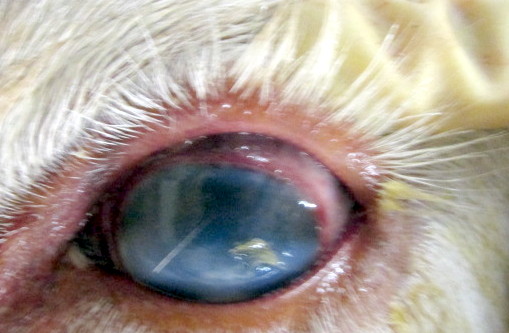

Gross Pathology: This animal was an adequately fleshed, minimally autolyzed white adult female bovine of 500 Kg body weight. The nasal planum was crusted and ulcerated, with red underlying tissue. There was separation of the coronary bands that affected all coronary bands. All teats are covered by crusts, revealing red tissue beneath. Externally both corneas are cloudy and mottled, with reddening of the conjunctiva and milky fluid in the anterior chambers. The corneas became cloudy after fixation and sections of the eye revealed severely increased corneal thickening and exudate in the anterior chamber and behind the lens. The vitreous was cloudy as well.

Lymph nodes associated with the mammary gland, head, neck, and thorax were enlarged to 3-5 times expected volume. There were oral ulcers, particularly on the sides of the thickest part of the tongue and little mucosa remains on the dental pad. The anterior third of the esophagus was uniformly dark red and the wall approached 1 cm in thickness. The abomasal mucosa in 1-1.5 cm thick and the abomasal mucosal folds are thereby accentuated. Punctate ulcers were evident in the mucosa.

Incision of the fixed globes revealed a thickened cornea, with rust red areas of vascularization, and coagulation of exudates in the anterior chamber and vitreous, causing their partial to complete opacity.

Gross Morphologic Diagnosis: None provided.

Laboratory results: Multiple tissues and swabs were positive for herpesviral sequences that were identified as sheep-associated malignant catarrhal fever virus by sequencing. The same samples were negative for sequences of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus, bluetongue, BVD and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus. NVSL testing was declared negative for foot and mouth disease virus.

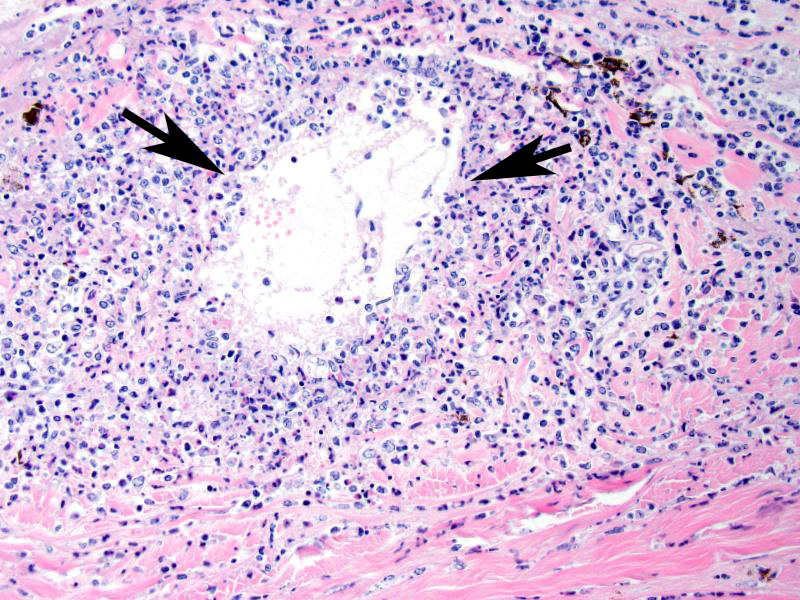

Microscopic Description (limited to the eye): Nearly every segment of the eye is inflamed or secondarily altered in this animal, with variability in the severity of inflammation between sites . Pink fibrillar edema fluid is present in the anterior chamber. There is pronounced edema of the corneal stroma, with attenuation, vacuolation and loss of the keratinocytes. Intense mixed, predominantly lymphocytic infiltration occurs in the limbus and extends into the cornea, as well as the conjunctiva and sclera. Small thin-walled blood vessels occur in the peripheral corneal stroma, and, beyond this, single file leukocytes align along the stromal fibers. Neutrophils contribute substantially to the population in the more central cornea. The iris and ciliary bodies also contain numerous lymphocytes, macrophages and intermixed neutrophils that exfoliate freely into the anterior and are adhered to the endothelial layer at the back of the cornea. The filtration angle is also filled with similar cells. The fibers of the vitreous are separated by fluid and leukocytes and there choroid is similarly affected. Scleral vessels and extraocular muscle and adventitia have less extensive infiltrates. Lymphocytes are visible in the walls of a few muscular vessels at the base of the iris in some sections.

Similar perivascular lesions (not shown) were associated with ulcerations were found in the skin, tongue, abomasum and in the brain, lung, kidney, heart and adrenal. Lymph nodes were enlarged, with hyperplastic cortical tissue and hemorrhages.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnoses: Eye: Severe lymphocytic vasculitis and perivasculitis, uvea and cornea, with corneal edema, erosion and vascularization.

Contributors Comment: Malignant catarrhal fever is caused by a rhadinovirus that cause polysystemic disease of cattle, bison, various deer and other ruminants (2). Most cases in cattle affect animals in the 8-24 month age range and have a mean duration of 71 days. Cattle surviving acute MCF have chronic lesions in medium caliber vessel and cornea, comprised of arteriopathy with variable recanalization. Microscopic lesions throughout the body are characterized microscopically by vasculitis. Anterior and posterior synechiae, edema and eventual fibrosis of the corneal stroma, and perforating ulcers and staphyloma are other common ocular lesions.

MCF-related rhadinoviruses have now known to be extremely variable in genetic sequences (3). OvHV-2 had some alleles that varied over 60% in genetic composition. Translation of 9.5 polypeptides revealed only 49% amino acid identity. However, the clinical signs of MCF in cattle from viral isolates originating sheep, bison, reindeer and cattle, as related to viral genotype, did not reveal differences.

Ocular disease is consistently present in the head and eye form but milder lesions can occur in other forms as well (6). In one study, there was no correlation between the degree of corneal edema at first examination and lethal disease outcome. Corneal edema began at the limbus in natural cases, and corneal erosion was common (5). Keratinization of the corneal epithelium, pyknosis and cytoplasmic vacuolation of epithelial cells were observed (4). Corneal perforations occurred and chronic scars common. The corneal edema and uveitis improved in all surviving cattle. Posterior segment disease was frequently present, but difficult to detect to the alterations in the anterior segment (6).

A review of lesions spontaneously occurring MCF-like disease in exotic hooved stock involved cases in 15 moose, 1 roe deer and 1 red deer. Frequent gross findings involved the eye and included conjunctivitis, corneal opacity and fibrin clots in the anterior chamber. Although OvHV-2 caused some cases, CpHV-2 caused others. Most cases occurred in farmed animals and zoos (1). The microscopic appearance of lesions was similar to those in cattle. Additional novel rhadinoviruses have been described in exotic hooved stock and cervids. (1) Pigs also develop ocular lesions resulting from MCF (2).

JPC Diagnosis: Eye: Panuveitis and vasculitis, lymphoblastic and necrotizing, diffuse, severe with ulcerative keratitis and corneal edema, Charolais, bovine.

Conference Comment: There was significant slide variation in this case. Additional morphologic diagnoses generated by conference participants included conjunctivitis, keratitis, and episcleritis depending on the plane of tissue sectioned.

Malignant catarrhal fever is caused by infections with the MCF virus group of ruminant Gammaherpesviridae (which are known as Rhadinoviruses in older texts).3 Of the pathogens in the MCF virus group, 6 are associated with clinical signs: Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 (carried by wildebeest) and 2 (carried by hartebeest), Ovine herpesvirus 2 which is endemic in domestic sheep, Caprine herpesviruses 2 (endemic in domestic goats) and 3 (affects white tailed deer and red brocket deer), and Ibex MCF virus which is carried by Nubian ibex and produces disease in bongo and anoa. 5 However, most natural outbreaks are due to Ovine herpesvirus 2 in sheep or Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 in African wildebeest.

MCF is characterized by marked T-lymphocyte hyperplasia which was prominent in conference discussion. 5 In the slides examined numerous lymphoblastic cells were present in various portions of the eye with prominent mitotic figures. The pathogenesis of MCF is presumed to start with infection of large granular lymphocytes that are subsequently transformed by the gammaherpesvirus. In fact, the OHV-2 genome has been detected in CD8+ T cells which are the predominant cell present in the perivascular inflammation. The pathogenesis of this disease is unclear, and although the invasive T cells are most likely cytotoxic T lymphocytes or T-suppressor cells the mechanism they use to cause such marked vasculitis has not yet been identified.5

Conference participants briefly reviewed various terms used to classify ocular inflammation such as: endophthalmitis (inflammation of the uvea, retina, and ocular cavities), panophthalmitis (inflammation of all of the ocular structures, including the sclera), anterior uveitis (inflammation of the ciliary body and iris), posterior uveitis (inflammation of the ciliary body and choroid), panuveitis (inflammation of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid), and chorioretinitis (inflammation of the choroid and the retina).7

In addition, these slides contained nice examples of the tapetum lucidum which is not commonly seen in microscopic sections. The conference moderator noted that in cats and dogs the tapetum is cellular and has a brick-like appearance; whereas in ruminants and horses, it contains more fibrous connective tissue with fibroblasts arranged linearly. Pigs were specifically mentioned because they are lacking a tapetum lucidum.1

Acute severe bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) and mucosal disease was mentioned as a differential. However, MCF usually affects multiple organs that are not involved in mucosal disease like liver, kidney, bladder, eye, and brain. Also, MCF produces lymphoid hyperplasia whereas lymphoid tissue in BVDV infections is atrophic.5

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory

University of Missouri

References:

1. Bacha WJ, Bacha LM. Color Atlas of Veterinary Histology. 3rd ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2012:268.

2. Li H, Gailbreath K, Flach EJ, et al. A novel subgroup of rhadinoviruses in ruminants. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:3021-3026.

3. OToole D, Li H. The pathology of malignant catarrhal fever, with emphasis on ovine herpesvirus 2. Vet Pathol. 2014; 51: 437-452.

4. Russel GC, Scholes SF, Twomey DF, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity of ovine herpesvirus 2 in samples from livestock with malignant catarrhal fever. Vet Microbiol. 2014;172:63-71.

5. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2.6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:131-136.

6. Vikøren T, Li H, Lillehaug A, et al. Malignant catarrhal fever in free ranging cervids associated with OVHV-2 and CPHV-2 DNA. J Wildlife Dis. 2006;42:797-807.

7. Wilcock BP, Njaa BJ. Special senses. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1.6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:446.

8. Whateley HE, Young S, Liggitt HD, et al. Ocular lesions of bovine malignant catarrhal fever. Vet Pathol. 1985;22:219-225.

9. Zemlji? T, Pot SA, Haessig M, et al. Clinical ocular findings in cows with malignant catarrhal fever: ocular disease progression and outcome in 25 cases (2007-2010). Vet Ophthalmol. 2012;15:46-52.