Signalment:

During diagnostic workup, there was mild C5-C6 disc protrusion noted on cervical myelogram. On post-contrast T1 weighted MR images, there was meningeal enhancement spinal cord through C1 and ventral to the brain stem and pons, as well as faint contrast enhancement in the cerebellum. On cerebellomedullary cistern cerebrospinal fluid aspirate cytology there was a severe mixed pleocytosis. Neospora and Toxoplasma PCR and serology, Cryptococcus latex agglutination, and bacterial cultures were all negative. Thoracic radiographs were unremarkable. Serum biochemistry findings were mild hyperglobulinemia and moderately elevated ALT and AST.

Therapeutic interventions included clindamycin, fluconazole, cytoarabine, and prednisolone at an immunosuppressive dose. The tentative clinical diagnosis was meningoencephalitis of unknown origin with concern about fungal disease or GME. The dog was discharged from the hospital 5 days after admission. During the following 2 weeks, the patient re-presented for weight loss, muscle wasting, and progressive ataxia leading to tetraparesis. The patient arrested shortly after presentation to urgent care in lateral recumbency and respiratory distress.

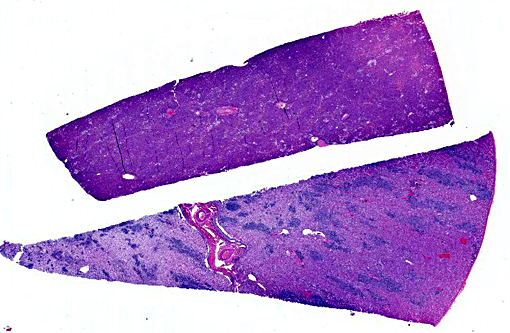

Gross Description:

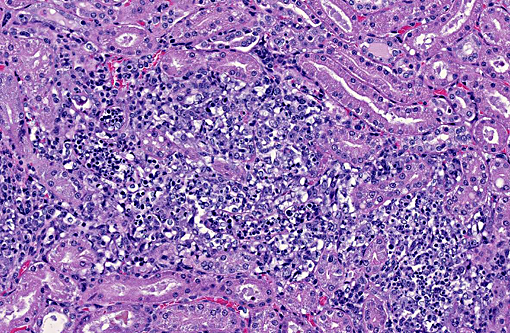

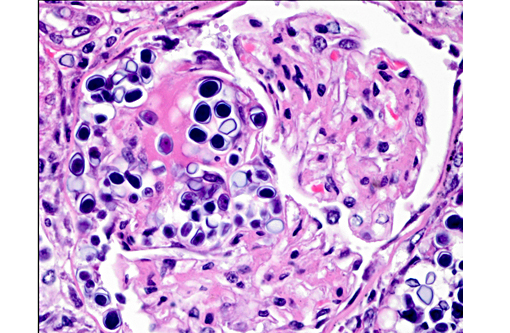

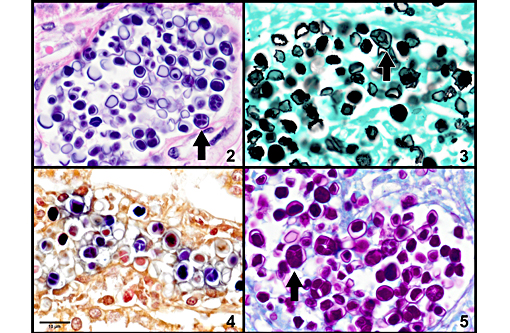

Histopathologic Description:

Of additional interest, sections of liver are provided, demonstrating organisms in sinusoids, multifocal hepatocellular necrosis, dystrophic mineralization, hydropic degeneration, and occasional portal tracts effaced by Prototheca sporangia and granulomatous inflammation. Hepatic lesions are variable and clusters of organisms are not captured in all sections.

In tissues not included for conference material, multifocal to coalescing perivascular and random granulomatous inflammation with organisms is present throughout the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, mesentery, lymph nodes, lung, myocardium, and meninges.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Ubiquitous in moist environments, Prototheca spp. are found in slime flux of trees, a variety of freshwater environments, soil, animal waste lagoons, and in great abundance in sewage.(7,9) Despite their relative ubiquity, disease in mammals is rare. The two known pathogenic species are Prototheca zopfii and P. wickerhamii. Previously reported mammalian species infected include cattle, dogs, cats, and humans.(4) In cattle, P. zopfii is reported to cause severe mastitis, due to ascending infection from environmental contamination.(6) In humans, three clinical forms of protothecosis are recognized: systemic infection, bursitis, and cutaneous lesions most commonly.(8) In cats, only the cutaneous form is reported, and presumed to be due to trauma. In dogs, systemic dissemination is most commonly reported. Organs frequently infected include the intestinal tract, liver, kidney, heart, eyes, and central nervous system.(4)

The specific pathogenesis of disseminated canine protothecosis is not well studied, largely due to the limited number of cases. Infection is thought to occur by ingestion, and penetration of the colonic mucosa, at which point severe hemorrhagic colitis and diarrhea are often the first clinical findings.(4) Much less frequently, neurologic disease is the first reported finding.(7) Systemic infection occurs through hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination to multiple organs, where colonization, necrosis, and granulomatous inflammation are associated with myocardial collapse, acute renal failure, hepatic failure, blindness due to chorioretinitis and uveitis with retinal detachment, as well as varying presentations of neurologic disease.(2,4,7) Protothecosis is associated with therapeutic or pathologic immune system impairment in both dogs and humans.(7,8) With or without immunosuppression, there may be numerous organisms in tissue sections with relatively mild inflammation. Greater numbers of ruptured, empty theca are associated with much more severe pyogranulomatous reactions.(1)

Many aspects of this case are fairly characteristic for systemic canine protothecosis, including reported immunosuppression. However, the diagnosis made at necropsy was unexpected, due to the local arid climate, and rarity of protothecosis in such environments. Travel history was more thoroughly investigated after necropsy findings, and the dog was reportedly in the Southeastern US from late December to early January.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, multifocal, moderate, with mild glomerulonephritis and numerous endosporulating algae.

2. Liver, hepatocytes: Degeneration and necrosis, multifocal, random, mild, with mineralization.

3. Liver, hepatocytes: Glycogenosis, multifocal, mild.Â

Conference Comment:

Protothecosis is typically observed as disseminated disease in dogs while it is also reported in cows, but as an important cause of mastitis. P. zopfii is most often associated with disseminated disease while P. wickerhamii usually associated with cutaneous infections.(3) The disseminated presentation in this case and the timeline of travel, development of urinary symptoms and subsequent neurologic signs would make for an interesting diagnostic exercise in detecting an immunosuppressive disorder and acquired Prototheca infection and correlating it with development of clinical signs.Â

Prototheca is one of the few pathogens which uniquely reproduce by endosporulation. The infective unit of these endosporulators is the endospore, which when implanted in tissues, grow into much larger sporangia. As a part of the maturation process of sporangia, endospores are produced and discharged effectively reinitiating the cycle. The other endosporulators of veterinary significance include: Rhinosporidium seeberi, Chlorella sp., Coccidioides immitis, and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis.Â

In this case, the hepatocellular glycogenosis was attricuted to the immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids noted in the clinical history. The cause for the random hepatocellular necrosis and mineralization was not evident.Â

References:

1. Cheville NF, MacDonald J, Richard J. Ultrastructure of Prototheca zopfii in bovine granulomatous mastitis. Vet Pathol. 1984;21:341348.

2. The Uvea: Canine ocular protothecosis. In: Dubielzig RR, ed. Veterinary Ocular Pathology, A Comparative Review. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2010:278.

3. Ginn PE, Mansell JL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders;2007:711-712.

4. Greene CE, Rakich PM, Latimer KS. Protothecosis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006:659665.

5. Haenichen T, Facher E, Wanner G, Hermanns W. Cutaneous chlorellosis in a gazelle (Gazella dorcas). Vet Pathol. 2002;39(3):386389.

6. J+�-�nosi S, Ratz F, Szigeti G, Kulcsar M, Ker+�-�nyi J, Lauk³ T, et al. Review of the microbiological, pathological, and clinical aspects of bovine mastitis caused by the alga Prototheca zopfii. Veterinary Quarterly. 2001;23(2):58-61.

7. Lane LV, Meinkoth JH, Brunker J, Smith SK II, Snider TA, Thomas J, et al. Disseminated protothecosis diagnosed by evaluation of CSF in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2012;41(1):147152.

8. Lass-Fl+�-�rl C, Mayr A. Human Protothecosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):230242.

9. Pore RS, Barnett EA, Barnes WC, Walker JD. Prototheca ecology. Mycopathologia. 1983;81:4962.

10. Pressler BM. Prothecosis and chlorellosis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:696-701.

11. Retovsky R, Klasterska I. Study of the growth and development of Chlorella populations in the culture as a whole: Basophilia and oxido-reduction relationships in Chlorella cells. Folia Microbiologica. 1961;6:127135.

12. Taniyama H, Okamoto F, Kurosawa T, Furuoka H, Kaji Y, Okada H, et al. Disseminated protothecosis caused by Prototheca zopfii in a cow. Vet Pathol. 1994;31(1):123125.