Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 16

January 24th, 2018

CASE IV: WSC 2017-2018 Case I (JPC 4100648).

Signalment: Adult, male, African green monkey, Chlorocebus sabaeus, primate.

History: This monkey was in a study to determine the efficacy of a therapeutic drug for treating pneumonic plague. All of the monkeys in this study were exposed to a lethal dose of aerosolized Yersinia pestis. Once an individual animal began displaying clinical signs, twice daily treatments were initiated with either a placebo (control group) or the therapeutic drug (experimental group). This monkey was in the experimental group and it developed clinical signs necessitating euthanasia on Day 15 after bacterial challenge. Note: All of the control animals died on Day 4 or Day 5.

This monkey was part of a research project conducted under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facility where this research was conducted is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and adheres to principles stated in the 8th edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

Gross Pathology: There were multiple fibrous adhesions between the left testis and the inner lining of the scrotum. In the areas of adhesion, numerous oval white nodules, measuring 1-2 X 2-3 mm, were located in the connective tissues over the tunica albuginea of this testis and within the surrounding scrotum. There were several fibrous adhesions between the right middle lung lobe and the mediastinum and between the right inferior lung lobe and the thoracic wall. An approximately 1 cm diameter firm nodule was palpated within the middle of the right inferior lung lobe.

Laboratory results: None provided.

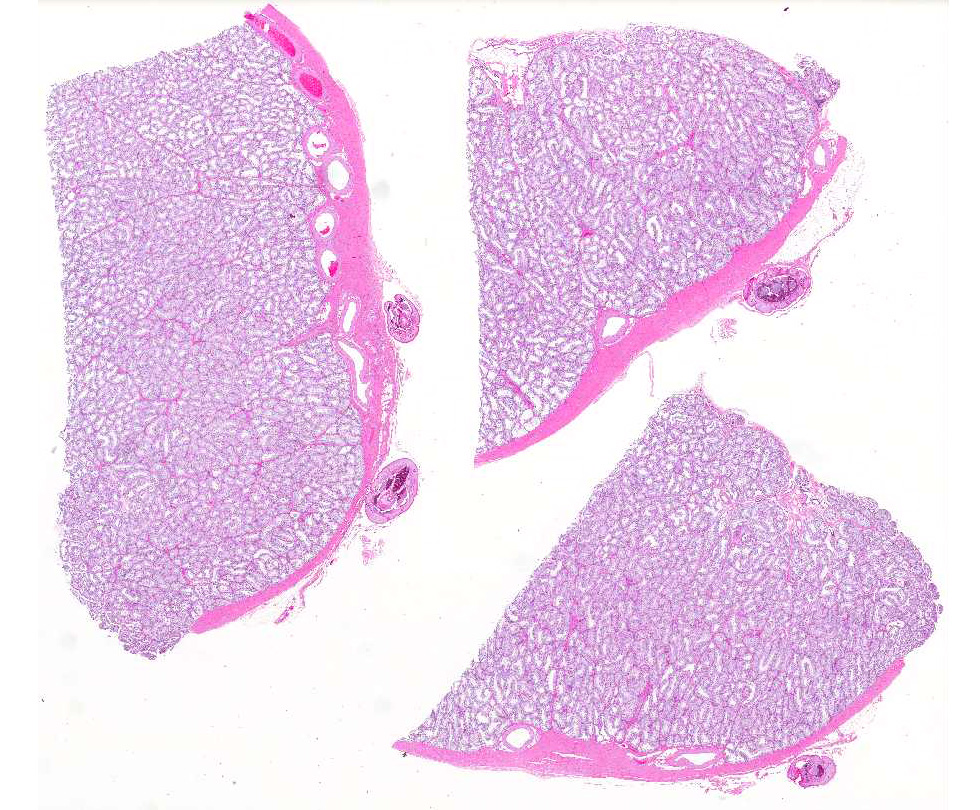

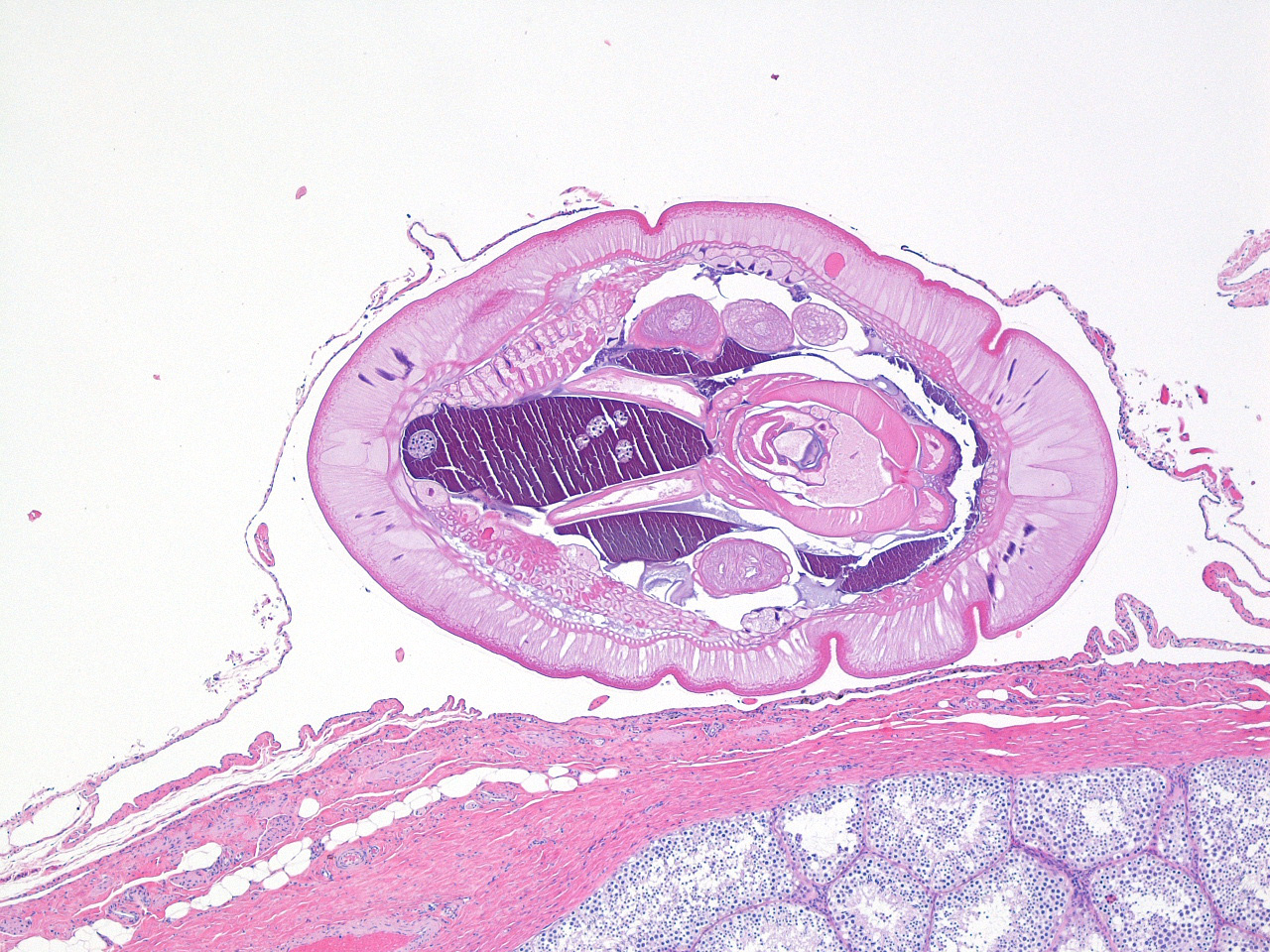

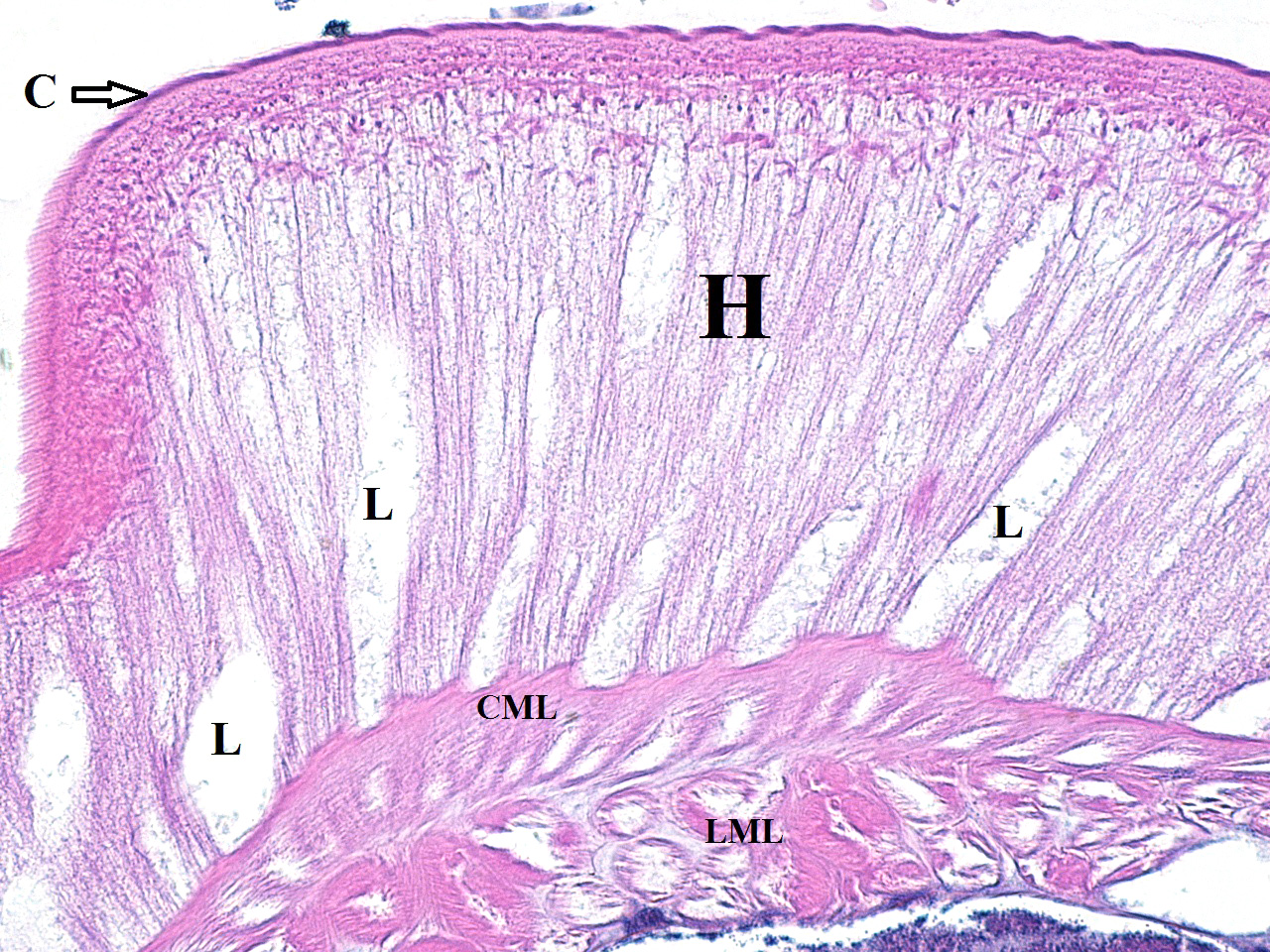

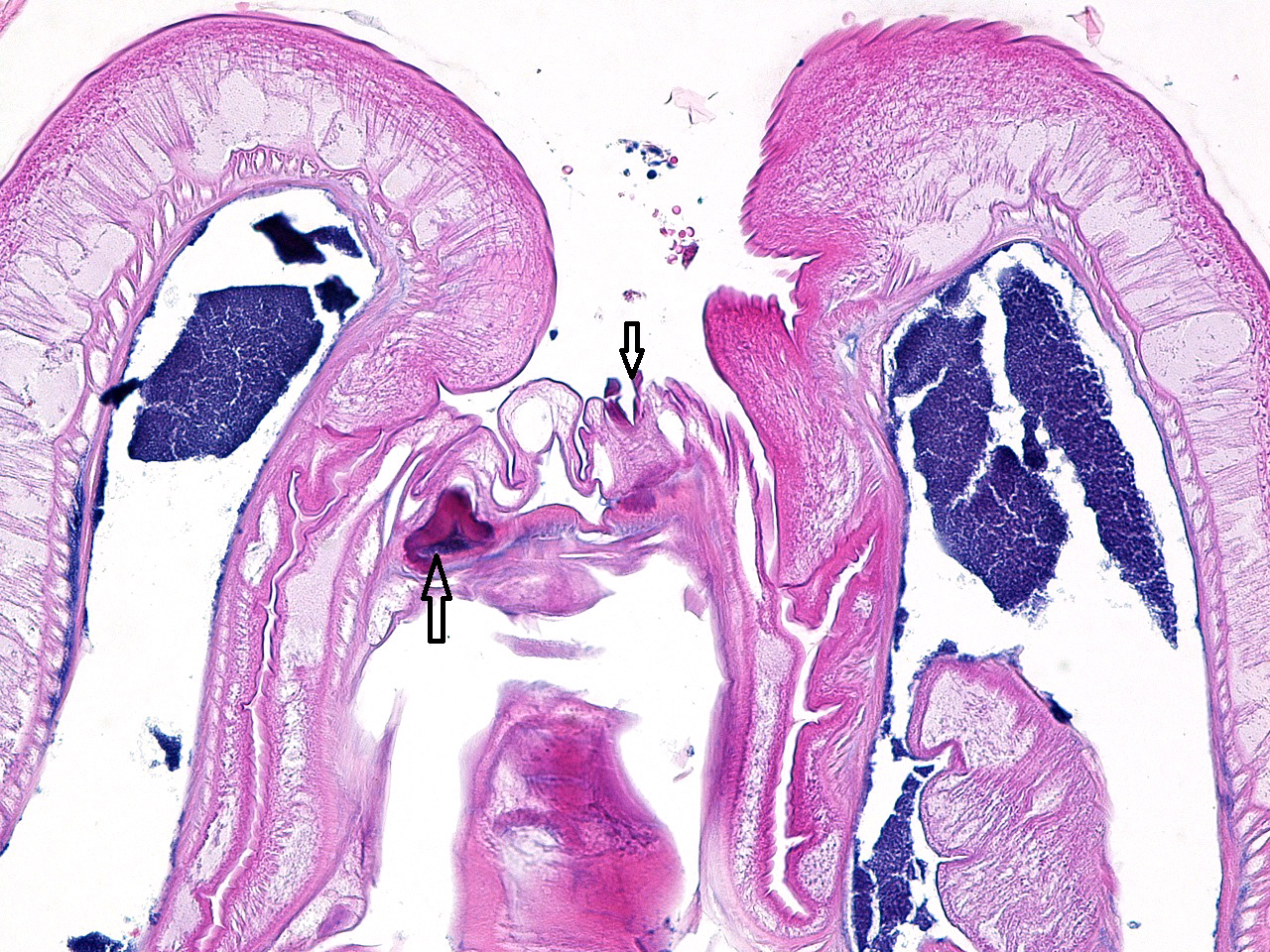

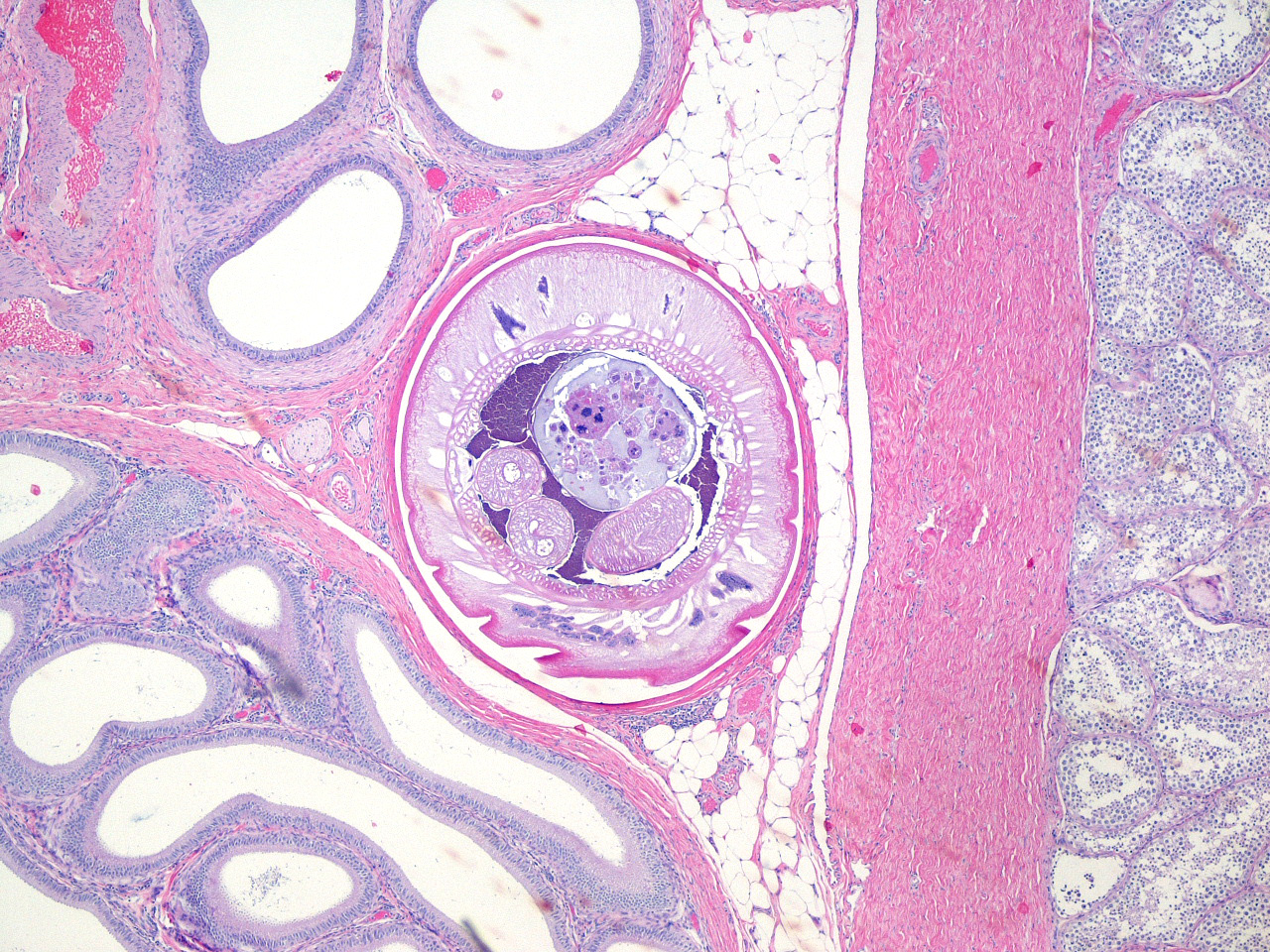

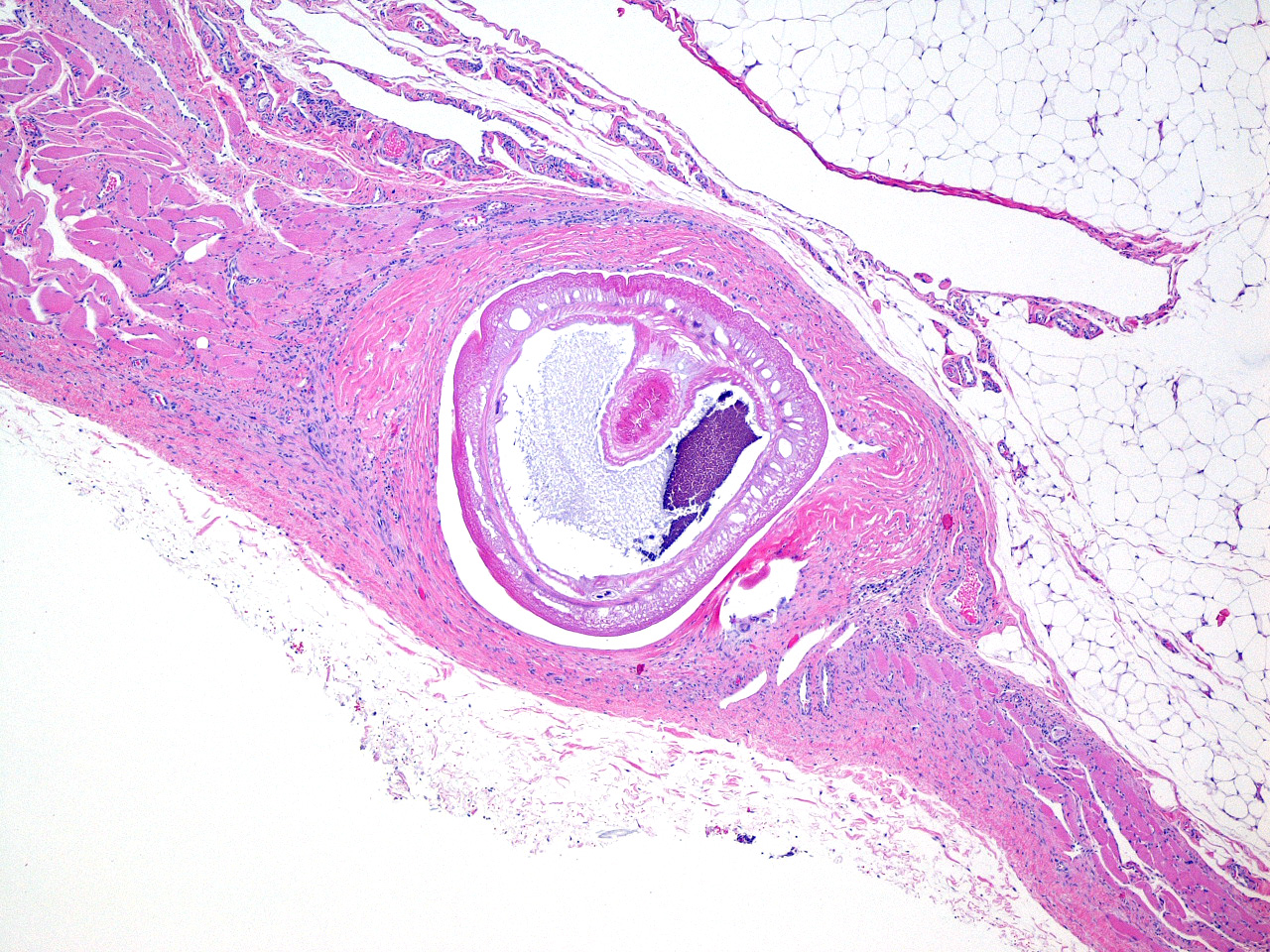

Microscopic Description: Testis (3 sections): Adjacent to the tunica albuginea, within the tunica vaginalis, there are four sections of a metazoan parasite measuring 1.5–2.5 mm in greatest diameter. The parasites have a cuticle, a wide hypodermis (100-200 µm thick) containing multiple lacunae, and two layers of muscle (circular and longitudinal) that border a pseudocoelom. In one section of the parasite, there is a retracted proboscis with spines. In other sections, the pseudocoelom contains oval muscular structures, measuring <100 X <200 µm, which have peripheral muscles and a central canal; these are consistent with lemnisci. Neither a digestive tract nor mature eggs are evident. Multifocally, the tunica vaginalis is fused with the tunica albuginea which results in the parasites being encysted.

In other tissue sections (not present on the scanned slide), the parasites reside in pseudocysts present in the left epididymis and the wall of the scrotum.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Testis/tunica vaginalis; multiple encysted larval acanthocephalan parasites

Contributor’s Comment: The anatomic features of the parasites in this monkey that are characteristic of the phylum Acanthocephala include: (1) a cuticle; (2) a thick hypodermis; (3) a pseudocoelom; (4) the lack of a digestive tract; (5) a proboscis with spines; and (6) the presence of lemnisci (pleural of lemniscus).4,5 No other types of parasites have lemnisci.5

As adults, Acanthocephelans are parasites of the intestinal tract of vertebrate hosts and different species have been reported in all classes of vertebrates (i.e. fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals).4 The adult worm everts it spiny proboscis and this is used for attachment to the host’s intestinal wall. This proboscis is responsible for the common names for Acanthocephalans: “thorny-headed” or “spiny-headed” worms.4,5 Lacking a digestive tract, the worms absorb nutrients through their body wall and the channels (lacunae) in the hypodermis probably aid in transporting absorbed nutrients.4

Adult female worms produce eggs, each containing a larva called an acanthor,2,4 which are passed in the feces of the host. The larvated eggs are ingested by an invertebrate intermediate host (usually an arthropod) in which the parasites develop and encyst at a stage called a cystacanth.2,4 Usually, the life cycle is completed when the definitive host ingests the infected intermediate host and the cystacanths are then released and develop into adults in the intestines of the definitive host.

However, cystacanths can occasionally use vertebrates as paratenic hosts.2,4,5 This occurs when a cystacanth-infected intermediate host is ingested by a vertebrate that is not a final host species; the cystacanths then encyst in the tissues of the paratenic host without any further maturation. The parasites in this monkey are consistent with cystacanths and the monkey is a paratenic host. A full necropsy was performed on this monkey and the only locations that these parasites were found were in the connective tissues around the left testis and epididymis. These parasites were deemed to be incidental findings of no clinical significance. The lung lesions noted grossly in this animal were areas of subacute to chronic inflammation attributable to the experimental bacterial challenge.

This African green monkey originated from a semi-feral colony on the island of St. Kitts in the Caribbean. The monkeys on St. Kitts are believed to have descended from escaped or intentionally-released “pets” on slave-trading ships in the 1600’s.1 They became established on the island (as well as the Caribbean islands of Nevis, Anguilla, Saint Maarten, and Barbados) and their population increased to a level so that their crop-raiding tendencies caused them to be described as a “pest species” on St. Kitts as early as 1700,1 where they are still considered to be an invasive pest.

The species of Acanthocephala in this monkey was not determined. However, the monkey most likely had plenty of opportunities to be exposed to potential intermediate hosts on St. Kitts before it was brought to the United States. Adult acanthocephalans in the genus Prosthenorchis have been reported in a variety of New World primates (NWPs) and cystacanths of these parasites have also been found encysted in the peritoneal membranes of NWPs.2,6 However, it is unlikely that the parasites in the monkey of this report are a species of Prosthenorchis because NWPs do not occur on St. Kitts. It is interesting to note that feral pigs are present on St. Kitts; this suggests the possibility that the parasites in this monkey might be cystacanths of the “thorny-headed worm” of pigs: Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus.

Note: Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

JPC Diagnosis: Testis, tunica vaginalis: Multiple encysted acanthocephalans, African green monkey (Chlorocebus sabaeus), primate.

Conference Comment: Acanthocephalans were first described by Italian author Francesco Redi in 1684. The name “Acanthocephala” (which is derived from the Greek akanthos, thorn and kephale, head) was coined by scientist Joseph Koelreuter in 1771 but not formalized until 1809. Acanthocephalans are simple parasites that lack many internal organs for increased efficiency. For instance, they lack a mouth or gastrointestinal tract, and the adult stages of the parasite live in the intestines of their host where they uptake nutrients that have been digested by the host. Thorny-headed worms have marked variation in size from species to species depending on the host and can reach up to 65 centimeters in length (Gigantorhynchus gigas). In addition to their physical size, there is variation in the size of many of their adult cells. Polyploidy is common with some species having up to 343n. Finally, some species of thorny-headed worms have an interesting life cycle and have been referred to by some as “body snatchers”. Generally, Acanthocephalans begin their life cycles within invertebrates, such as earthworms or crustaceans that live near water systems. When these invertebrates are infected, the thorny-headed worms cause the invertebrates to go towards the light (i.e. surface of the water or soil), where they will inevitably be eaten by a definitive host and allow for continuation of the life cycle.3

Contributing Institution:

US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases

Pathology Division

Fort Detrick, MD

http://www.usamriid.army.mil/>

References:

- The History of the St. Kitts Vervet Monkey. www.stkittsheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Vervet-Monkey-article.pdf.

- Bowman DW. Helminths. In: Bowman DW, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014; 227-229.

- Crompton D, Thomasson W, Nickol BB. Biology of the Acanthocephala. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1985:27.

- Eberhard ML. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Bowman DW, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 10th ed. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014; 430.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC; Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1999.

- Strait K, Else JG, Eberhard ML. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif SD, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Academic Press; 2012; 258-260.