Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 10, Case 2

Signalment:

2-month-old, male-intact, French bulldog, Canis familiaris, dogHistory:

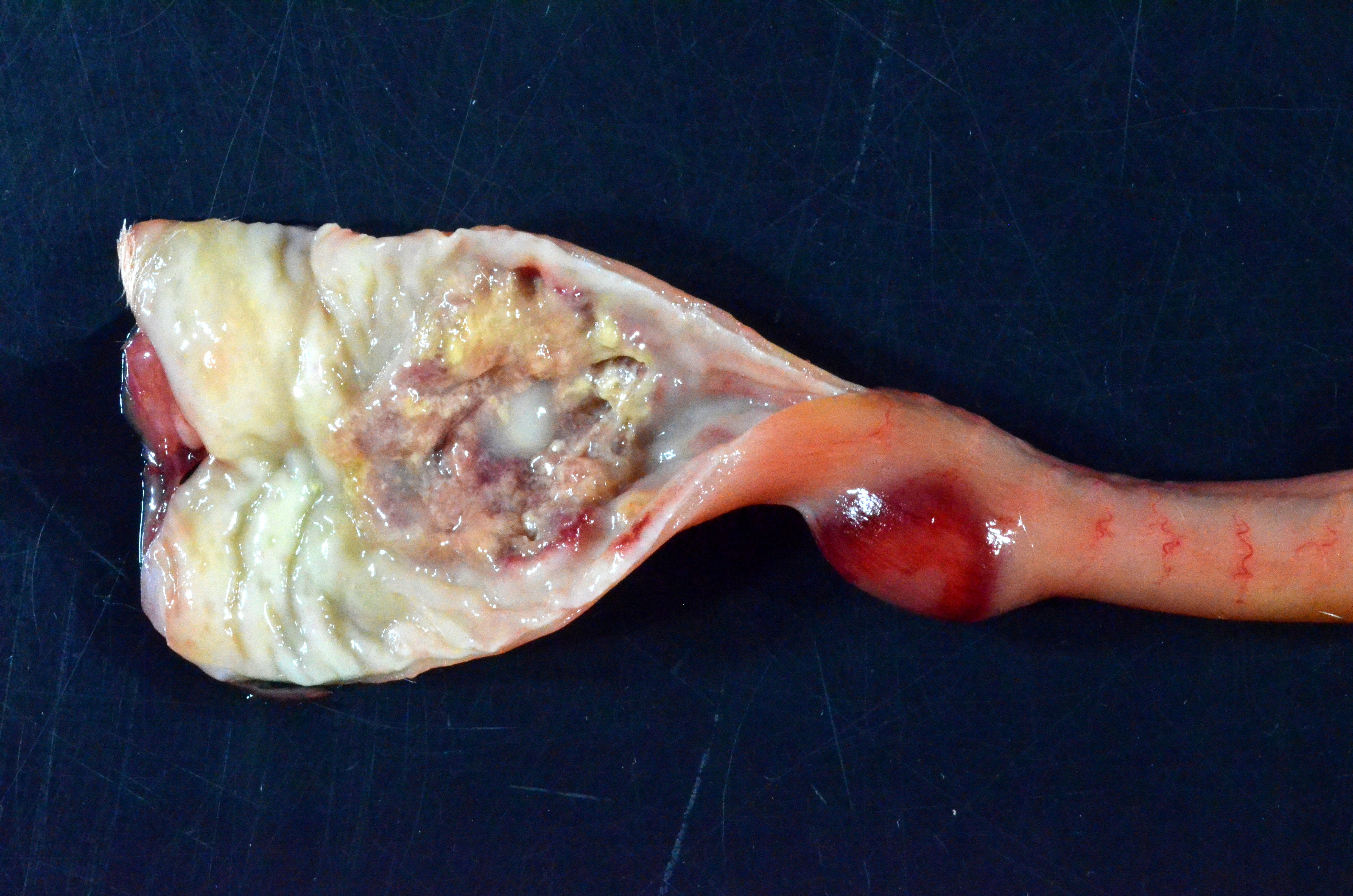

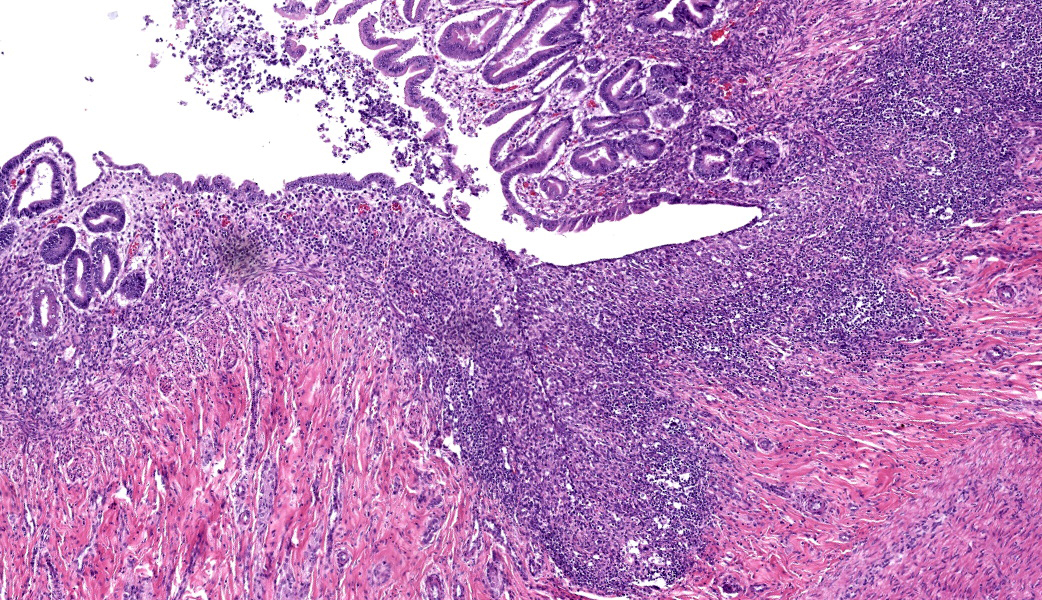

Gross Pathology: The subcutis is diffusely expanded by up to 1 cm of gelatinous, translucent, pale yellow material (edema).On the serosal surface of the distal colon are two, 10 x 15 x 4mm, ovoid, expansile, targetoid (pale pink center surrounded by a hyperemic rim) foci, located 15mm apart and approximately 2cm orad from the anus. The corresponding colonic mucosa of these foci is friable thickened up to 8 mm thick, with an irregular corrugated mucosal surface that is mottled tan to brown, with a central area of pasty, white exudate (pus, ulceration and necrosis).

Laboratory Results:

Parvovirus antigen SNAP test: negative (premortemFecal culture: negative for Salmonella sp., C. difficile, C. perfringens.

Pan-fungal PCR (through UGA) negative

Oomycete PCR (through UGA), positive for Pythium spp.

Microscopic Description:

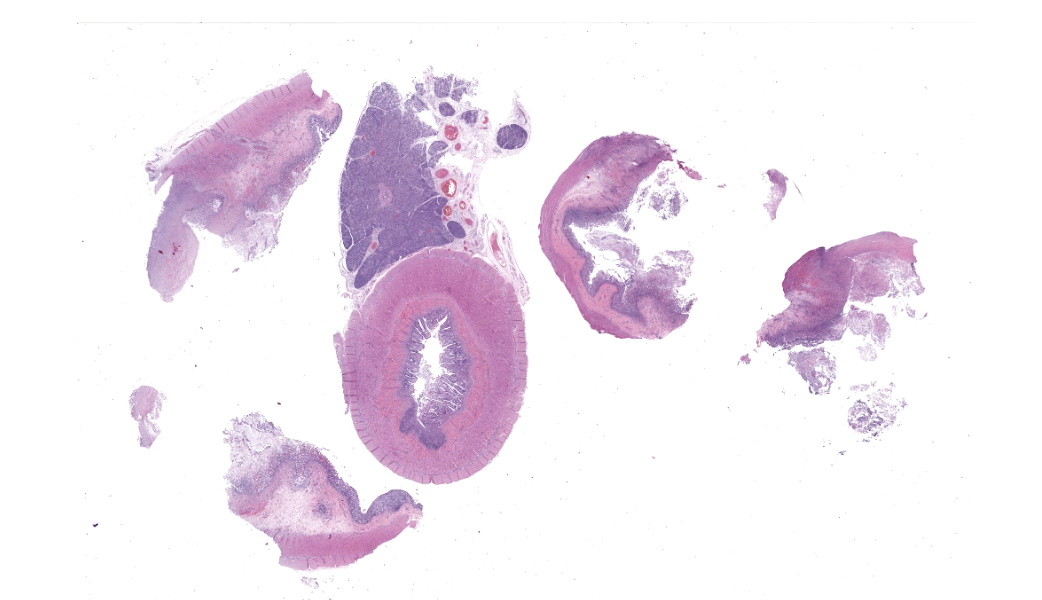

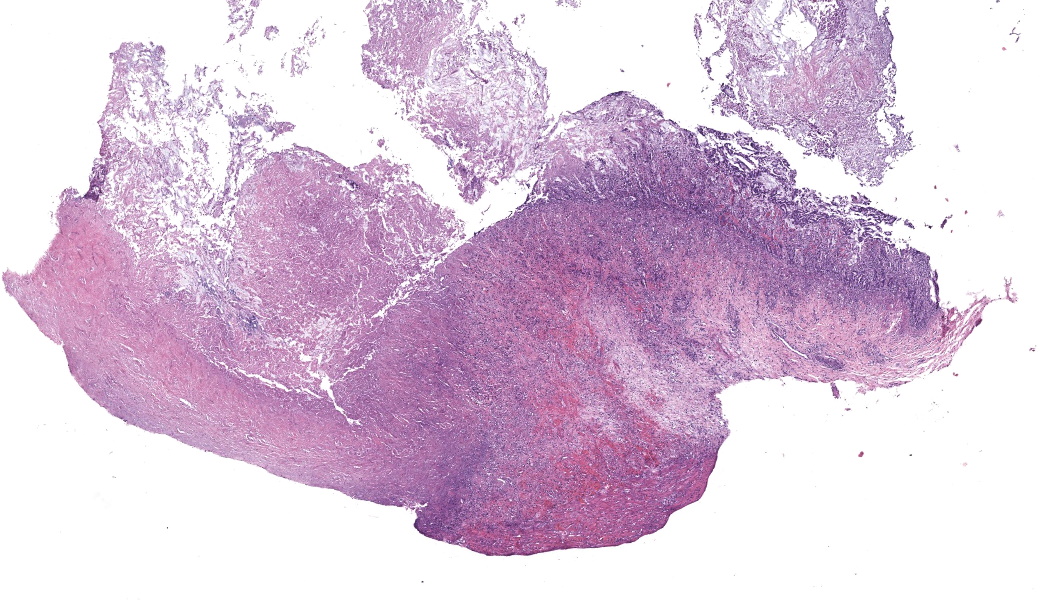

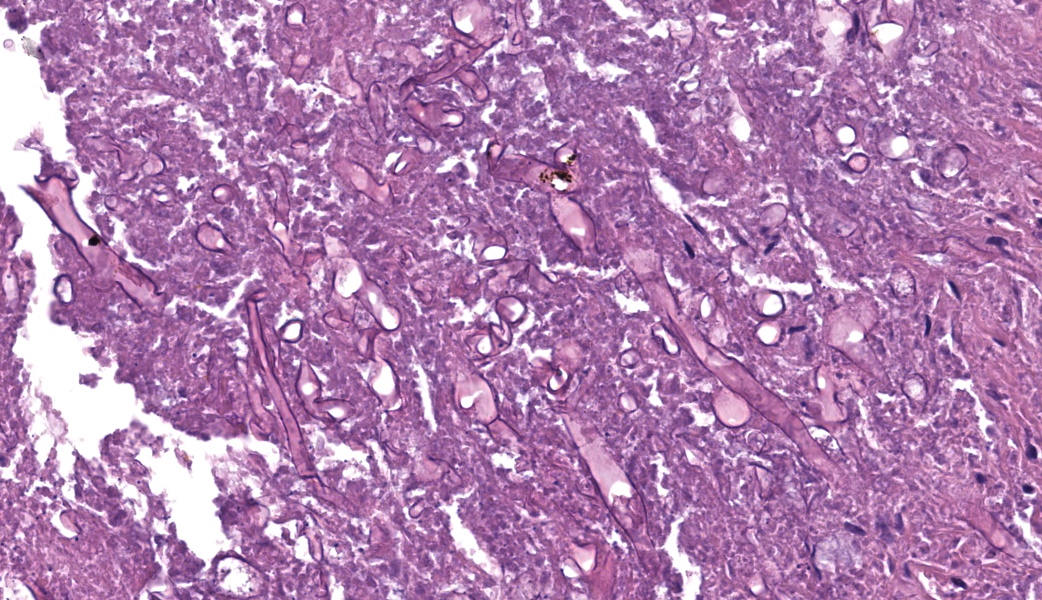

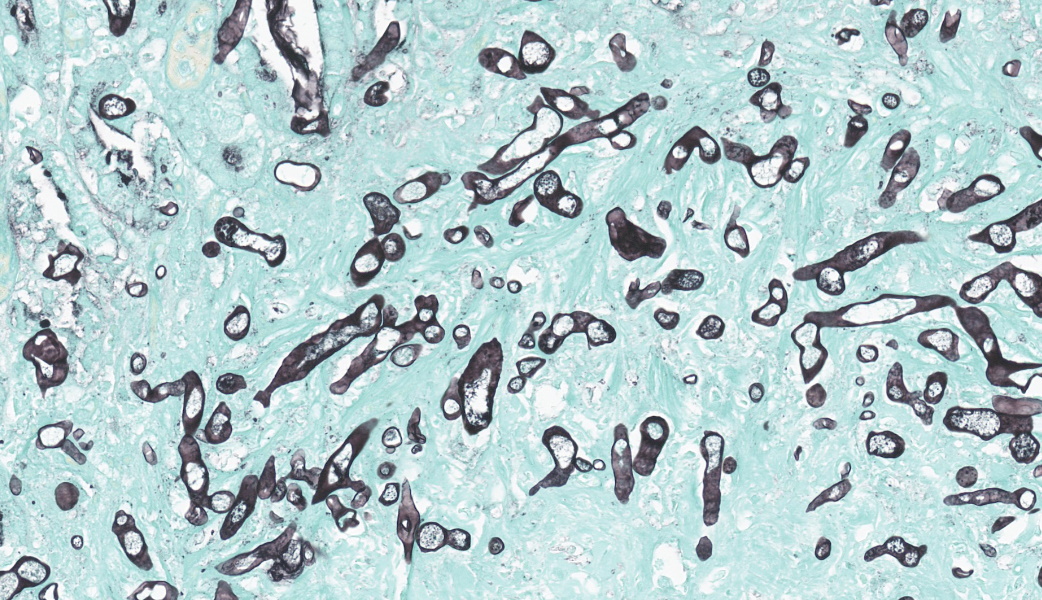

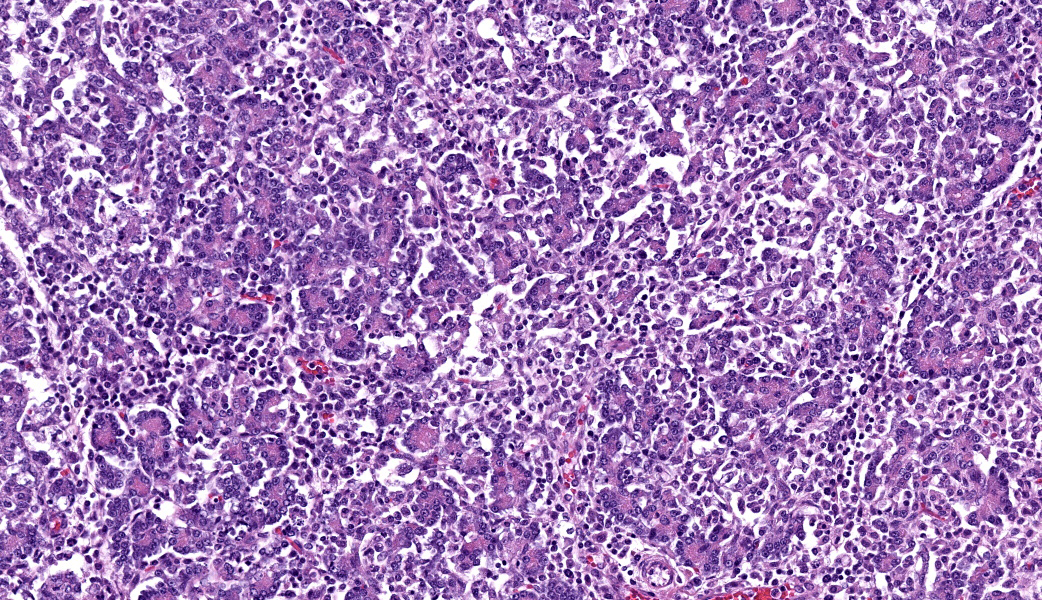

This slide consists of three sections of segmentally ulcerated and necrotic colon and one section of less severely affected duodenum with attached pancreas. Within the colonic sections the mucosa is segmentally necrotic with loss of cellular architecture and replacement with amorphous to fibrillary eosinophilic material (fibrin, proteinaceous exudate), scattered karyorrhectic debris, and frequent 4 to 9 um wide, hyphal elements that have 1um wide, bright eosinophilic cell walls that are nonparallel, and demonstrate irregular, non-dichotomous, lateral branching and rare septation. The underlying submucosa, muscular layers, and occasionally the serosa (transmural), are infiltrated by the previously described hyphal structures, scattered karyorrhectic debris, mixed, swollen leukocytes (neutrophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes, and rare eosinophils), and extravasated erythrocytes (hemorrhage). The intestinal wall is variably necrotic, with loss of cellular detail and loss of differential staining. Medium sized arteries within the submucosa frequently contain dense mats of hyphal structures, with individual hyphae present within the vessel walls. In segments of mucosa adjacent to the completely ulcerated regions, fibrin thrombi are frequently present within lamina propria vessels. The necrotic luminal surface is lined by dense sheets of ovoid, bright eosinophilic, 5 x 5 to 5 x 8 um structures with a thin cell wall, and irregular, pale eosinophilic, internal vacuoles (zoospores), as well as loosely clustered dark basophilic, 1 to 2 um diameter, round structures (bacteria).The section of duodenum demonstrates multifocal ulceration down to the submucosa, with replacement by fibrin and swollen leukocytes. Clusters of the previously described yeast structures are present within the fibrinous, luminal exudate. Villi are diffusely, markedly blunted (crypt: villous ratio ~ 1:1), fused, and the lamina propria is markedly expanded by densely packed mixed leukocytes, that include mainly lymphocytes and histiocytes, with fewer multinucleated giant cells, plasma cells, and granulocytes.

The interstitium of the pancreas is moderately to markedly expanded by dense streams of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and rare, fragmented neutrophils.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Colon: Fibrinonecrotizing and ulcerative, granulomatous and neutrophilic, transmural colitis, multifocal to segmental, severe, acute on chronic, with fibrin thrombi, intralesional hyphae, and intraluminal zoospores, and coccobaccili

- Duodenum: Lymphoplasmacytic and fibrinonecrotizing duodenitis, moderate to marked, chronic, segmental with villous fusion, blunting, and intraluminal zoospores

- Pancreas: Lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic pancreatitis, marked, multifocal to coalescing

Contributor's Comment:

This case represents a florid case of intestinal pythiosis. The etiologic agent of pythiosis in mammals is Pythium insidiosum, which causes cutaneous, intestinal, and occasionally upper respiratory infections in a wide variety of species. P. insidiosum is an aquatic oomycete (clade Stramenopila/ heterokonts, class Oomycetes, order Pythiales, family Pythiaceae), with many of its closest relatives being plant pathogens that are the cause of what is colloquially known as “root rot”. Pythium spp. are closer relatives to algae than fungi, and care should be taken to not miscategorize these organisms into the kingdom Fungi.These water molds, unsurprisingly, preferentially grow in aquatic, warm environments. The preferable temperature range for growth ranges from 34 to 36C (93 to 97F) but growth is still possible in temperatures up to 45C (113F).2 Historically, the distribution of this organism has been limited to tropical and subtropical environments, and in recent years (starting in 2003) increasing numbers of cases have been reported in higher latitude regions, such as Northern California and the Chincoteague national wildlife refuge in Virginia.1,5,6 Speculation about the cause for the expansion in the geographic range of this organism includes the adoption of environmental modifications such as rice field flooding in Northern California.1

Intestinal infection typically occurs through ingestion of contaminated water. Though typically not seen in tissue sections, this case included abundant intraluminal zoospores, which are the infective stage of this organism.2 Motile zoospores are produced asexually from the bulbous sporangia formed at the terminal ends of the organism’s hyphae.4 Sexual reproduction resulting in oogonia also may occur, but the size of the intraluminal structures in this case was not consistent with oogonia, which measure 23 to 30 microns in diameter.4 Oogonia/ oospores, unlike zoospores, can persist in sub-optimal environmental conditions and may survive for months to years.1

Infection of the digestive tract is the most common form of pythiosis in the dog; infections of young, large-breed dogs are most commonly reported, but have also been reported in female and small-breed dogs.1,5 Digestive tract pythiosis has also been reported in small ruminants, and horses.2,11 Cutaneous pythiosis occurs in dogs, horses, cats, humans, cattle, as well as a number of exotic species.1,7 Additionally, rhinofacial pythiosis (“bullnose”) has been reported in sheep in Brazil.2

The intestinal form of pythiosis typically involves segmental thickening with associated ulceration of any portion for the gastrointestinal tract wall, from stomach to colon with variable enlargement of associated lymph nodes.11 Occasionally a distinct mass-like lesion composed of granulomatous and fibrous tissue will form; necrotic coagula known as “leeches” or “kunkers” can be embedded within the granulation tissue.11 Histologically, intestinal infections consist of mural to transmural pyogranulomatous inflammation with concurrent lymphadenitis, lymphangitis, and in severe cases, peritonitis. Eosinophils, though not a prominent feature in this case, are frequently present in addition to pyogranulomatous inflammation; this is presumably due to a Th2 shifted immune response that has been associated with documented increased serum concentrations of Il-4, Il-5, and IgE.9 In contrast to the presently discussed case, hyphal structures (as described above) are frequently difficult to discern with hematoxylin and eosin staining alone, and silver staining is often needed for visualization of the organism.11 PAS staining is frequently poor to entirely ineffective due to lack of chitin production by the organism.11

The histologic lesions of intestinal pythiosis are not unique, and differential diagnoses based on histology include Lagenidium spp. (another oomycete), as well as a number of fungi, including zygomycetes, most notably Conidiobolus spp., and Basidiobolus spp.2,11 Culture, serology, or molecular techniques (PCR, as used in this case) are needed for definitive diagnosis; interestingly, some panfungal PCR tests have been reported to amplify Pythium spp., likely due to the reliance on amplification of the internal transcribed spacer region, which is a pan-eukaryotic, non-coding segment of DNA.8

Unfortunately, intestinal infection with this organism can frequently be fatal. Treatment with antifungal agents is largely unsuccessful; it has been hypothesized that this may be due to the lack of ergosterol (the target of -conazole drugs) in oomycete cytoplasmic membranes.9 Surgery to remove infected tissue is frequently the treatment of choice, and various immunotherapies have also been pursued with mixed success.9

Contributing Institution:

University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, Anatomic Pathology servicehttps://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/hospital/support-services/lab-services/anatomic-pathology-service

JPC Diagnoses:

- Colon: Colitis, necrotizing and pyogranulomatous, subacute, multifocal, severe, with numerous hyphae, zoospores, and hyphal vascular invasion.

- Duodenum: Duodenitis, ulcerative, subacute, multifocal, moderate.

- Pancreas: Pancreatitis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, subacute, diffuse, marked, with acinar atrophy.

JPC Comment:

This was a truly phenomenal case of pythiosis and conference participants felt spoiled with how visible the hyphae and zoospores were on the slide. Oomycetes usually are much more challenging to find and tend to appear as “hyphal ghosts” from The Great Beyond, only visible with use of special paranormal photography...or a GMS stain. A classic entity, the contributor of this case provided an exceptional write-up on Pythium insidiosum and other major differentials in this case.Conference discussion largely focused on a review of oomycete characteristics, most of which were covered by the contributor, as well as a few interesting facts about them that were not in the contributor’s write-up. For one, infective Pythium insidiosum zoospores display chemotaxis towards animal hairs, intestinal mucosa, and wounded tissue. How neat is that? Pythium is also equipped with some impressive virulence factors that enable it to cause death and destruction regardless of it ends up in the intestinal tract or in the skin. Its cell wall components include cellulose and β-1,3-glucan. Beta-glucan, in particular, can be a target for host immune cells. 3.10 Despite these being literal components of its own cell wall, Pythium comes equipped with a glucan 1,3-beta glucosidase, which breaks down β-1,3-glucan. While that may seem a bit counterintuitive, glucan 1,3-beta glucosidase acts as a virulence factor for Pythium by breaking down β-1,3-glucan from the cell wall, allowing the pathogen to dampen the host’s immune responses and enable it to invade tissues.3,10 This enzyme is identified as an “immunodominant” protein and is upregulated by Pythium during infection, suggesting it plays a key role in both disease progression and in triggering host immunity.10

Pythium also sports virulence factors such as has heat shock protein 70, chaperone proteins, enolase, elicitins, and urease. Much like it does in mammalian cells, heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) and other chaperone proteins protect Pythium from damage by binding to and stabilizing stress-induced misfolded proteins, preventing their aggregation and degradation and facilitating proper folding. HSP70 is induced under stressful conditions, such as heat (mammalian body temperature is pretty spicy if you’re an oomycete), cold, infection, and inflammation. Another virulence factor, enolase, is primarily a glycolytic enzyme that catalyzes a crucial step in glycolysis to generate ATP. Enolase is also considered an immunodominant antigen.

Elicitins are proteins that are secreted by oomycetes, especially in those that infect plants, but are also seen in Pythium insidiosum and have dual functions. Elicitins can act as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to trigger host defense responses, or they can act as virulence factors by manipulating host defenses. They also act as sterol carriers, binding and transporting sterols that are essential for their growth and invasion. The dual role of elicitins makes their function context-dependent and varies based on the host and specific oomycete.

Lastly, the P. insidiosum urease, Ure1, hydrolyzes urea to produce nitrogen, which aids the organism’s survival. Fun fact: P. insidiosum’s urease shares similarity with the virulence factor urease, URE1, of Cryptococcus neoformans. In cases of pythiosis, urease is striding to the forefront as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target because humans, as well as many domestic species, do not produce their own form of this enzyme.

References:

- Berryessa, N., Marks, S., Pesavento, P., Krasnansky, T., Yoshimoto, S., Johnson, E. and Grooters, A.. Gastrointestinal Pythiosis in 10 Dogs from California. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2008;22:1065-1069.

- Carmo PMS, Uzal FA, Riet-Correa F. Diseases caused by Pythium insidiosum in sheep and goats: a review. JVDI. 2021;33(1):20-24.

- Chechi JL, Franckin T, Barbosa LN, Alves FCB, Leite AL, Buzalaf MAR, Delazari Dos Santos L, Bosco SMG. Inferring putative virulence factors for Pythium insidiosum by proteomic approach. Med Mycol. 2019;57(1):92-100.

- De Cock AW, Mendoza L, Padhye AA, Ajello L, Kaufman L. Pythium insidiosum nov., the etiologic agent of pythiosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1987 Feb;25(2):344-9.

- Fischer JR, Pace LW, Turk JR, Kreeger JM, Miller MA, Gosser HS. Gastrointestinal Pythiosis in Missouri Dogs: Eleven Cases. JVDI. 1994;6(3):380-382.

- Jara M, Holcomb K, Wang X, et al. The Potential Distribution of Pythium insidiosum in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2022;8.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Chapter 6 - Integumentary System In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Volume 1 (Sixth Edition): W.B. Saunders, 2016;509-736.

- Meason-Smith C, Edwards EE, Older CE, et al. Panfungal Polymerase Chain Reaction for Identification of Fungal Pathogens in Formalin-Fixed Animal Tissues. Veterinary Pathology. 2017;54(4):640-648.

- Mendoza L, Newton JC. Immunology and immunotherapy of the infections caused by Pythium insidiosum. Med Mycol. 2005;43(6):477-486.

- Rujirawat T, Patumcharoenpol P, Lohnoo T, Yingyong W, Kumsang Y, Payattikul P, Tangphatsornruang S, Suriyaphol P, Reamtong O, Garg G, Kittichotirat W, Krajaejun T. Probing the phylogenomics and putative pathogenicity genes of Pythium insidiosum by oomycete genome analyses. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4135.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Chapter 1 - Alimentary System In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Volume 2 (Sixth Edition): W.B. Saunders, 2016;1-257.e252.