Signalment:

3-year-old male Australian shepherd (

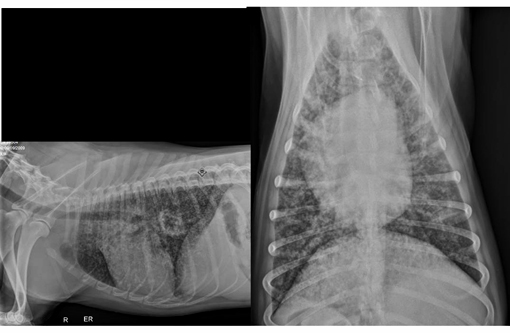

Canis lupus familiars), canine.A three-year-old male Australian Shepherd presented to the University of Florida Emergency Service for coughing, right hind-limb lameness, and a fever which did not respond to antibiotic therapy. He was adopted two months prior to presentation from a breeder in Illinois with no history of prior illness. He lives at home on a farm with several other adult dogs. They are primarily outdoor dogs and have free access to two acres. Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient became febrile and started coughing. He was placed on Baytril, chloramphenicol and prednisone, however his cough did not resolve. He was then taken to a specialist and prescribed fluconazole. Physical examination revealed harsh lung sounds bilaterally, right hind limb lameness with no neurological deficits, enlarged right popliteal lymph node, dry non-productive cough, and elevated temperature (temp 104.3). Thoracic radiographs were obtained and revealed diffuse miliary interstitial pulmonary pattern bilaterally. Owner elected for humane euthanasia.

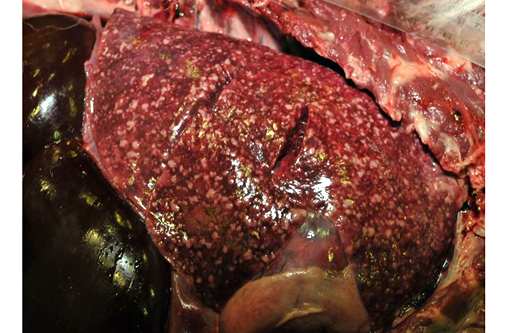

Gross Description:

LUNGS: The lungs are diffusely mottled light tan to dark red and contain toonumerous-to-count light tan, irregular, firm, granulomatous nodules in all lung fields. The granulomas range in size from 0.2 x 0.1 x 0.1cm to 5.0 x 2.5 x 2.5cm (left caudal lung lobe). The granulomas are slightly raised above the parenchymal surface and extend throughout all cut surfaces. There are only 2-3 of these larger than 5 mm diameter. The remaining parenchyma is diffusely dark red, wet, and heavy. All sections float low in formalin.

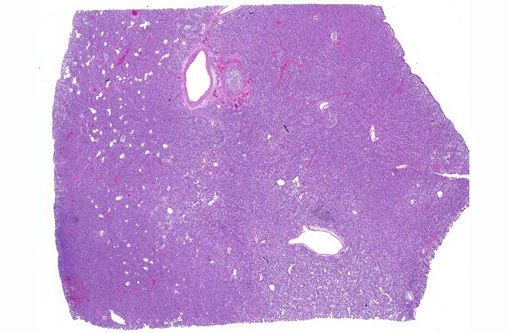

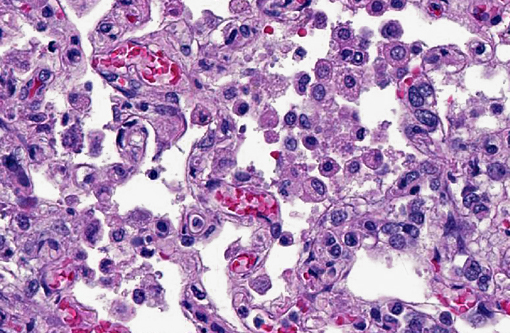

Histopathologic Description:

Lung: The alveolar capillaries are diffusely congested and there is lightly eosinophilic, homogenous material within 95% of the alveolar air spaces (alveolar edema). Approximately 40% of the lung parenchyma is effaced by pyogranulomatous inflammation. The interstitium is disrupted by numerous large, multifocal to coalescing pyogranulomas that are composed of a central area of necrotic debris and degenerate neutrophils, surrounded by a layer of macrophages and occasional multinucleated giant cells admixed with and surrounded by abundant degenerate neutrophils. Within the granulomas are numerous intracellular and extracellular 8-15 μm diameter argyrophilic round yeast with a 2-3 μm thick clear to basophilic, refractile capsule and a central, basophilic, granular nucleus (GMS stain). Yeasts frequently exhibit broad-based budding. There is mild to moderate, multifocal perivascular edema surrounding large vessels.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Granulomatous interstitial pneumonia, chronic, diffuse, severe, with fungal organisms consistent with

Blastomyces dermatitidis, lung.

2. Granulomatous lymphadenitis, multifocal, severe, with fungal organisms consistent with

Blastomyces dermatitidis, cranial mediastinal, tracheobronchial, and right popliteal lymph nodes.

Condition:

Blastomyces dermatitidis

Contributor Comment:

Blastomyces dermatitis is a dimorphic, saprophytic fungus most commonly associated with the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.(6) The primary route of infection is inhalation, with young male dogs of hunting and working breeds most commonly affected.(3) Clinical signs follow physiologic dysfunction of the affected tissue and infection is frequently associated with underlying immunosuppression.(3) Although

Blastomyces dermatitidis does infect both dogs and humans and is therefore considered zoonotic, infection is thought to originate from inhalation of spores from the soil.(6) No cases of direct transmission from animals to humans have been reported; however, dogs are up to 10 times more likely to acquire infections and are considered a sentinel species.(4) Due to its aggressive pathologic nature and potential of infection by inhalation, culture of the organism is not recommended due to the risk of transmission to staff.(5)

Infection begins with the inhalation of mycelial fungal conidia from contaminated soil. Following inhalation, conidia undergo nonspecific phagocytosis and killing mediated by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), monocytes, and alveolar macrophages. The infection is most commonly self-limiting; however, in select cases the primary infection is not eliminated and conidia are converted to the yeast phase at body temperature.(3) The yeasts are encapsulated by a thick cell wall and are more resistant to phagocytosis and killing. Local replication occurs via asexual budding and systemic dissemination via hematogenous and lymphatic routes is common.(2) Dissemination to multiple organ systems has been reported including cutaneous, ocular, CNS and bone.(2)

Although 85% of fungal pneumonia is reported to be attributed to blastomycosis, other differentials for fungal pneumonia should be considered and include:

Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans and

Aspergillosis. Differentiation and definitive diagnosis is best determined by the combination of geographic location, clinical presentation and histopathologic findings.(6)

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, granulomatous, diffuse, severe, with patchy type II pneumocyte hyperplasia.

Conference Comment:

Despite examining multiple sections, repeating fungal stains and consulting with the JPC Department of Infectious Disease, we were unable to definitively demonstrate the double-contoured, broad-based budding yeast of

Blastomyces in the submitted slides. The clinical history, gross findings and histologic lesions are all consistent with

Blastomycosis; thus we dont dispute the contributors diagnosis and rather attribute it to the variation that comes with cutting hundreds of slides.Â

Blastomycosis is one of the dimorphic fungi, whose transition from the mycelial form, known as conidia, to the yeast form is thermally dependent and takes place in tissue where temperature exceeds 37

oC. Conidia are readily phagocytosed by neutrophils and macrophages while yeast are more resistant, thus this conversion enables its pathogenicity. Also facilitating infection is the appropriately-named surface protein BAD-1 which mediates adhesion to host cells and modulates the inflammatory response by suppression of TNF-α production.(3)

While the lung is the most commonly affected site, Blastomyces dermatitidis can cause a disseminated infection where lesions are commonly found in lymph nodes, eyes, skin, subcutaneous tissues, bones and joints.(3) It is also one of the listed causative agents of granulomatous disease associated with hypercalcemia. The mechanism behind hypercalcemia has not been proven; however, it is suspected the population of macrophages produce 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol. Also known as calcitriol, it is the active form of vitamin D which increases calcium uptake from the gastrointestinal tract.(5)

References:

1. Arceneaux KA, Taboada J, Hosgood G. Blastomycosis in dogs: 115 cases (1980-1995). J Amer Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213(5):658-664.Â

2. Bateman BS. Disseminated blastomycosis in a German shepherd dog. Can Vet J. 2002;43(7):550552.

3. Caswell J. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:641-642.

4. Cote E, Barr SC, Allen C, Eaglefeather E. Blastomycosis in six dogs in New York state. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;210:502-504.

5. Ferguson DC, Hoenig M. Endocrine system. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan & Prasses Veterinary Laboratory Medicine Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:301.

6. Legendre A. Blastomycosis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2006:569-576.