Signalment:

Gross Description:

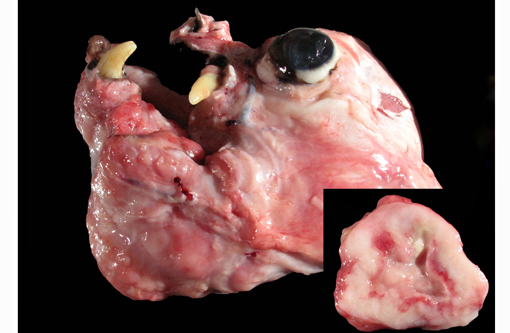

The lungs were diffusely mottled, tan to dark red and crepitant. There were multifocal, round, tan, slightly raised nodules ranging from pinpoint to 4 mm diameter throughout all lung lobes, but affecting less than 1% of the pulmonary parenchyma. One pedunculated tan nodule was present on the right caudal lobe. On cut section the pulmonary nodules were tan.

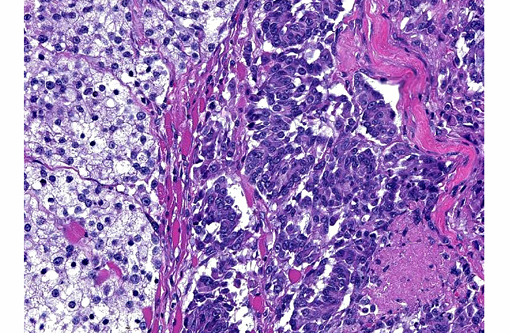

Histopathologic Description:

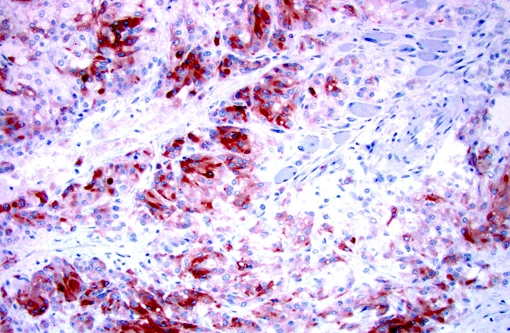

Immunohistochemistry for Melan-A, S100, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin were prepared at the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Less than 2% of neoplastic cells within the periphery of each lobule had strong intracytoplasmic immunopositivity and less than 10% of the neoplastic cells throughout the mass had weak to moderate intracytoplasmic immunopositivity for Melan-A. Approximately 50% of the neoplastic cells had weak intracytoplasmic immunopositivity for Chromogranin A. The neoplastic cells were immunonegative for S100 and Synaptophysin.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In dogs, malignant melanomas are the most common oral tumor and have variable breed and gender predilection.(3,7-9) These tumors are often heavily pigmented and grossly appear black; however, in some cases, these tumors are variably pigmented or completely unpigmented (amelanotic), and appear grossly white.(3,7,8) The degree of pigmentation does not indicate biologic behavior or aid in prognosis.(3,8) Malignant melanomas often metastasize, with the regional lymph nodes being the most common site, but also commonly spread to distant sites (ex. lung) through the blood and lymphatics.(3,9) Histologically, the cell morphology of malignant melanomas can range from round/polyhedral/epithelioid cells to spindloid cells to mixed (a combination of the two)(3,8); however, one defining histologic feature of the these tumors is often junctional activity(4), which can be seen as tumor infiltration crossing between the basal epithelium of the mucosa and the submucosa.Â

Most often, well-differentiated round/polygonal/epithelioid cell melanocytic tumors with abundant pigmentation are easily diagnosed; however, amelanotic and spindloid appearing tumors are quite often diagnostically challenging. Special stains [Fontana-Masson, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA)], immunohistochemistry, and/or electron microscopy can be used to aid in the diagnosis of amelanotic tumors.(1,3,5,7,8,10) Amelanotic melanomas are generally immunopositive for tryrosinase-related proteins 1 and 2 (TRP-1 and TRP-2), Melan-A, melanocytic antigen PNL2, HMB-45, microphthalmia transcription factor (MiTF), S100, tyrosine hydroxylase, tyrosinase, and vimentin(3,5,7-10); however, according to Smedley et al. PNL2, Melan-A, TRP-1 and TRP-2 as a group provide the most diagnostic information for canine oral amelanotic melanomas.Â

In human medicine, melanocytic tumors are often further classified allowing for integration of morphology, location, and biologic behavior; however, this classification system is not currently applied in veterinary medicine.(8) According to Eyden et al., while not currently a subclassification of malignant melanoma, neuroendocrine differentiation is a rarely seen variant. The three currently reported human cases of this variant had predominantly epithelioid cell morphology, variable pigmentation, and immunopositivity either in the primary tumor or metastases for both melanocytic and neuroendocrine markers. Ultrastructurally, the assessed cases (2 of 3) revealed neuroendocrine granules and no melanosomes.(6) Although electron microscopy was not performed on the current case, the cell morphology, architecture, and immunophenotype are consistent with an amelanotic melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation; which has currently not been reported in dogs.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Nuclear atypia and mitotic activity is directly correlated with prognostic behavior in melanomas at all locations. Immunohistochemistry has recently been evaluated as an additional prognostic tool. Ki67, a protein expressed only in growth and mitotic phases of the cell cycle, is considered a measure of tumor growth fraction and its expression has been correlated with outcome in canine melanomas comparable to nuclear atypia and mitotic index.(2) Additionally, immunodetection of RACK1, a protein expressed at high levels in melanocytes, may be a specific marker aiding in not only identifying melanomas but also offering progonostic value as its expression is also consistently correlated with nuclear atypia and mitotic index.(4)

References:

1 Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:387-402.

2. Bergin IL, Smedley RC, Esplin DG, Spangler WL, Kiupel M. Prognostic evaluation of Ki67 threshold value in canine oral melanoma. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):41-53.

3. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Toronto: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007:29-30.

4. Campagne C, Jule S, Alleaume C, et. al. Canine melanoma diagnosis: RACK1 as a potential biologic marker. Vet Pathol. 2013;50(6):1083-1090.

5. Choi C, Kusewitt DF. Comparison of Tyrosinase-related Protein-2, S-100, and Melan A Immunoreactivity in Canine Amelanotic Melanomas. Vet Pathol. 2003;40:713-718.

6. Eyden B, Pandit D, Banerjee SS. Malignant melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of three cases. Histopathology. 2005;47:402-409.

7. Gelberg HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, and peritoneal cavity. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:329.

8. Head KW, Cullen JM, Dubielzig RR, et al. Histological Classification of Tumors of the Alimentary System of Domestic Animals. Schulman FY, ed. 2nd series, Vol.10. Washington, DC: AFIP, CL Davis foundation, and WHO; 2003:33-35.

9. Ramos-Vara JA, Beissenherz ME, Miller MA, et al. Retrospective study of 338 canine oral melanomas with clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical review of 129 cases. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:597-608.Â

10. Smedley RC, Lamoureux J, Sledge DG, Kiupel M. Immunohistochemical Diagnosis of Canine Oral Amelanotic Melanocytic Neoplasms. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):32-40.