CASE 3: T18-6702 (4152981-00)

Signalment:

1-year-old, Female, German shepherd, dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The dog exhibited neurological signs, had difficulty in walking, was not able to swallow, was drooling saliva, and was apparently blind. Encephalitis was suspected on clinical grounds; the dog was euthanized, and the carcass was submitted for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

On external examination, it was noted that the dog was found in a poor body condition. Upon opening the carcass, the submandibular lymph nodes were moderately to markedly enlarged. Extensive multinodular mass that involved mediastinal lymph nodes and adjacent left side lungs was present in the thorax. The mass apparently compressed the adjacent thoracic esophageal segment. A small area of creamy exudate consistent with inspissated pus was present on cut surface, while grayish white surface was evident in the remaining nodular growths when cut. Right side lung was adhered to the diaphragm and the parietal pleura by moderate fibrous growth. Intestines had loose contents. There was a focal brainstem hemorrhage adjacent to cerebellum. There was no other grossly visible lesion.

Laboratory results:

Brain was negative for rabies.

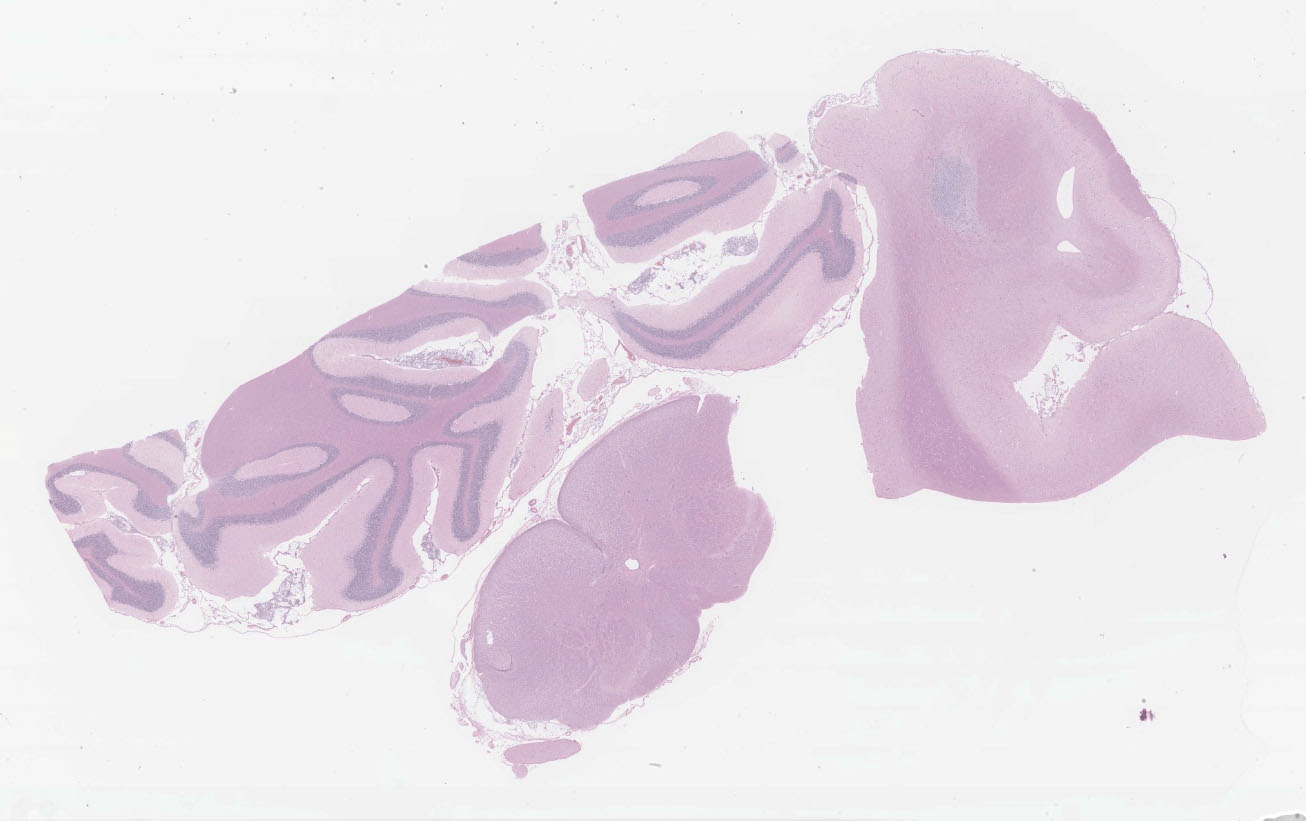

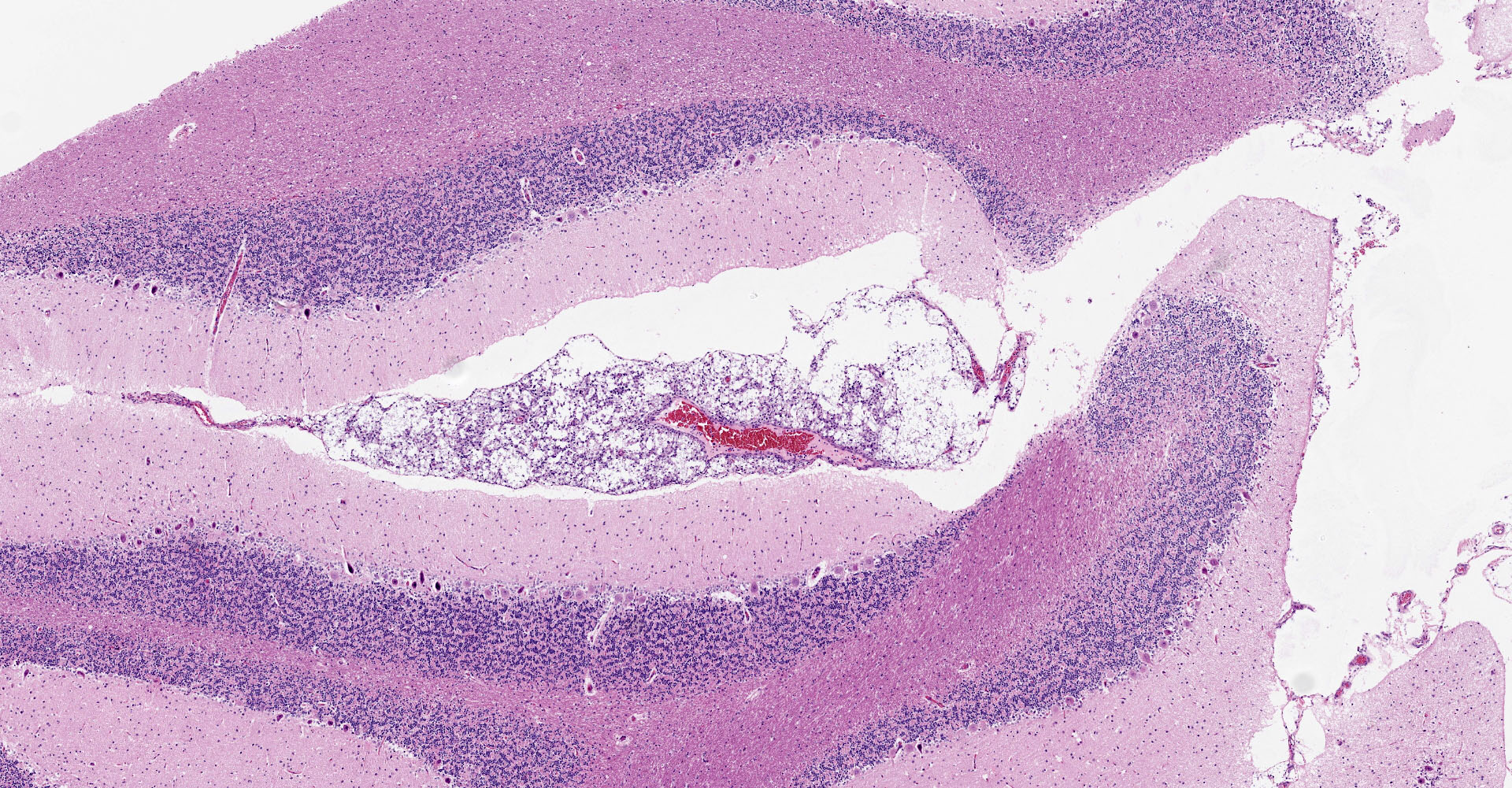

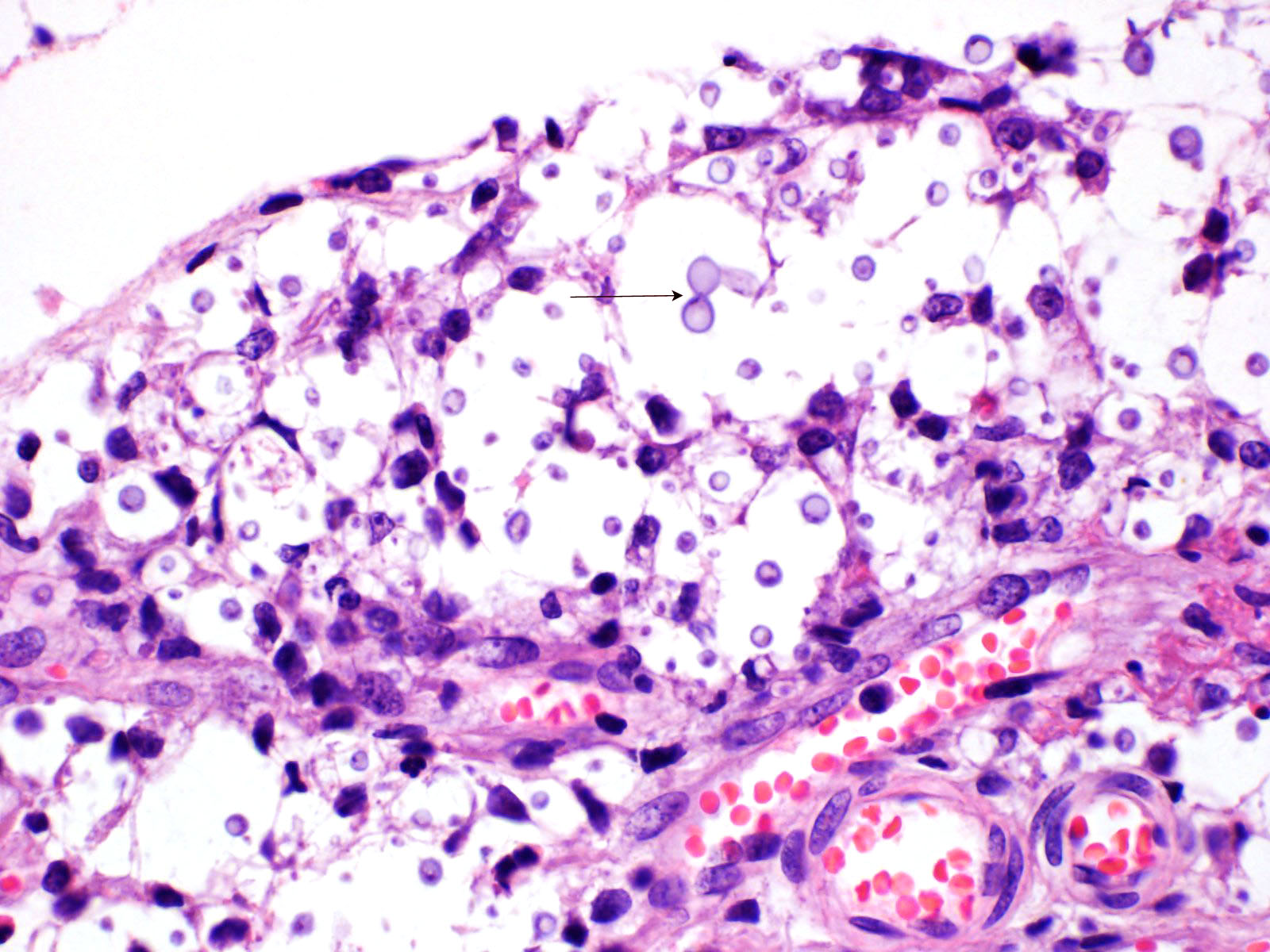

Microscopic description:

Multifocal to focally extensive areas of granulomatous inflammation that contained abundant fungal yeasts admixed with macrophages were observed in the meninges of the brain. The fungal yeasts measured about 4-20 microns in diameter occasionally exhibiting a narrow-based budding and had thick transparent capsule consistent with Cryptococcus species. Similar lesions with abundant fungal yeasts were observed in multiple tissues and organs (slides not included) including skin, lungs, and lymph nodes.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Multifocal, moderate to severe granulomatous meningitis with intralesional fungal yeasts consistent with Cryptococcus species. There was granulomatous pneumonia, pleuritic, lymphadenitis and dermatitis (slides not included) with intralesional similar fungal yeasts consistent with disseminated cryptococcosis.

Contributor's comment:

Multifocal to focally extensive severe, granulomatous to pyogranulomatous meningitis, dermatitis, pneumonia, pleuritis, lymphadenitis, peri-neuritis (optic nerve), splenitis, and with intralesional abundant fungal yeasts consistent with disseminated cryptococcosis were observed on microscopic examination.

Cryptococcosis is a mycosis caused by yeasts of genus Cryptococcus. The genus Cryptococcus can be divided into 2 groups: the pathogenic complex of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, and the ?less pathogenic? saprophytes, Cryptococcus laurentii, Cryptococcus magnus, and Cryptococcus albidus (although the species in the saprophyte group have been recently identified as pathogens in non-canine domestic animals).2 Mainly C. neoformans and C. gattii affect humans and animals. The yeasts are widely distributed in the environment and are typically associated with avian droppings and decaying wood.3 Cryptococcosis is distributed particularly in North America (Southern California, Western British Columbia), and on the east coast of Australia, while it has remained sporadic to date in Europe.1

Cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii is now being considered an important infectious disease both in humans and animals. The organism is isolated from environmental sources such as plant materials and avian excreta, where the fungus finds its ecological niche to reproduce, disperse and become the possible source of infections for the host.7 Various domestic and wild mammals may be infected with Cryptococcus, including cats, dogs, ferrets, horses, camelids, goats, sheep, cattle, dolphins, koalas and other marsupials. Cryptococcosis most often occurs by inhalation of fungal yeasts in suspension in the air. The organisms lodge in the nasal, paranasal, and pulmonary tissues before spreading more widely by blood or direct extension1,3 into other tissues including the central nervous system and cutaneous tissues.

Cryptococcus neoformans, an opportunistic fungus, is a commonly incriminated species in cryptococcosis. Immunosuppressive or debilitating diseases and iatrogenic glucocorticoids or cytotoxic chemotherapy is usually associated with cryptococcosis. There also was moderate demodicosis in the sections of skin in the dog in this report. C. neoformans presents a wide distribution in the environment and is associated mainly with avian droppings and decaying wood and most infections are linked to immunocompromised conditions. Similar to human cryptococcosis, the most likely route of infection in dogs and cats is inhalation of basidiospores or desiccated yeast cells during environmental exposure. Therefore, the nasal cavity is potentially the initial site of infection. Consequently, the most frequent clinical signs observed in veterinary medicine are associated with the upper and lower respiratory tracts.3 The incidence of cryptococcosis is lower in dogs than in cats. Cryptococcosis particularly affects dogs under 6 years old. American Cocker Spaniels, Great Danes, Doberman Pinschers, and German Shepherds appear to be overrepresented.1 The majority of canine cryptococcosis cases are reported as neurologic, disseminated, or nasal infections. A boxer dog is reported to suffer from primary alimentary cryptococcosis without dissemination.9

Cases of cryptococcosis in dogs are characterized mainly by the presentation of a systemic dissemination of infection, resulting in life threatening illness. The disease may occur in any age, but the majority of the cases have been reported in dogs younger than 6 years of age.7 Clinical signs may vary depending on the severity of lesions and affected organs or tissues. In dogs, disseminated disease is frequent, severe, and often involves atypical sites. Major systems affected include central nervous system, eyes, urinary system, and nasal cavity. Lytic bone lesions can cause lameness. Mild to moderate non-regenerative anemia, leukocytosis, monocytosis, and eosinophilia are common findings. There can be hematogenous spread, particularly to the central nervous system with incubation times 2-13 months or longer.2

Diagnosis of the infection can be made by routine culture techniques, histopathology and validated serological tests in all of medical mycology.8 Cytological examination is also a good technique to detect Cryptococcus spp. in clinical cases3 although a negative result in the cytology does not rule out the possibility of an infection.7 Cryptococcus spp. could also be identified on fecal examination.9

Cryptococcosis remains hard to treat in dogs and cats, with the treatment consisting of the use of systemic antifungals that can be used as monotherapy or in combination. There is, however, not a clearly established protocol.1 The entire resection of masses is reported to be an important step for the treatment of some patients. Long-term association of flucytosine, itraconazole and amphotericin B on postoperative care resulted in no relapse. The use of fluconazole and terbinafine were also associated with success in the treatment of gastrointestinal cryptococcosis.3. Canine abdominal cryptococcosis is reported to be successfully treated with a triazole therapy alone.9

The prognosis for cryptococcosis is poor and directly correlates with the extent and the magnitude of the disease at the time of the diagnosis. Implementation of an adequate treatment and rigorous monitoring can, however, quite substantially increase the chances of survival. Despite establishment of a suitable antifungal treatment, the prognosis remains poor.1 The presence of clinical signs of CNS disease has been shown to be a significant predictor of mortality.2

Contributing Institution:

The University of Georgia

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathology

Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Laboratory

43 Brighton Rd, Tifton, GA 31793, USA

JPC diagnosis:

1. Cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord: Meningoencephalitis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with numerous extracellular and intrahistiocytic encapsulated yeasts.

2. Cerebrum, presumptive pyriform lobe: Glioma.

JPC comment:

Cryptococcus neoformans is well summarized by the contributor. A polysaccharide capsule is the most critical virulence factor for this pathogen. The ability to form the capsule is dependent on local factors and host signals, such as the presence of glucose, iron, CO2, which are sensed by the G-protein coupled receptor Gpr4 and the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) pathway. The cAMP/PKA pathway also coordinates capsule production through the regulation of transcription factors, the ubiquitin proteasome system, and the iron regulator Cir1. Some virulence factors, such as melanin, are also regulated through the cAMP/PKA pathway, while others (proteases, urease, phospholipase, and superoxide dismutase) are regulated in other ways.5

Acapsular Cryptococcus spp yeasts have been reported in animal infections occasionally. The variants without a capsule are typically less virulent than those with a functional capsule. A basic component of the fungal cell wall is a-1,3-glucan encoded by the AGS1 gene, which critical for the correct capsule-cell wall attachment. Variants with disruptions to the AGS1 gene (ags1D strain) are characterized by yeasts that are functionally alive, but without any capsule on the cell wall surface, despite the correct presence of capsule components in sufficient quantities.4

While not regularly reported in veterinary literature, Cryptococcus spp can also form cells of varying size. While the normal yeast size is approximately 4-6 mm in diameter, titan cells are larger than 12 mm in diameter, and sometimes larger than 100 mm in diameter. Like many other regulatory mechanisms in this genus, titan cell production is also regulated by the cAMP/PKA pathway.4,5 On the other size of normal, Cryptococcus spp also has the ability to make micro cells that are usually 2-4 mm in diameter and may be adapted for growth in macrophages.4

Interestingly, a few slides (and the distributed scanned slide) for this case contain a focus of glial proliferation within what appears to be a section of pyriform lobe. Our opinion on this focus, which lacked inflammatory cells as well as yeasts and is based solely on morphology is that it represents a small glioma. Dr. Jey Koehler of Auburn University agreed in consult. Olig2, GFAP, IBA1, CD3, and PAX5 were performed, but this focus was unfortunately not present in the submitted unstained slides.

References:

1. Barbry J?B, Poinsard AS, Gomes E, et al. Cryptococcosis with ocular and central nervous system involvement in a 3?year?old dog. Clin Case Rep. 2019; 7:2349?2354.

2. Block K, Battig J. Cryptococcal Maxillary Osteomyelitis and Osteonecrosis in a 18-Month-Old Dog. J Vet Dent, 2017; 34 (2):76-85.

3. de Abreu DPB. Machado CH. Makita MT. et al. Intestinal Lesion in a Dog Due to Cryptococcus gattii Type VGII and Review of Published Cases of Canine Gastrointestinal Cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia. 2017; 182:597?602.

4. Frank KM, McAdam AJ. Infectious Diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 10th Ed. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier. 2020;385.

5. Garcia-Rubio R, de Oliveira HC, Rivera J, Trevijano-Contador N. The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;10:2993.

6. Mayer FL, Kronstad JW. Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends in Microbiology. 2020;28(2):163-164.

7. Pérez F, Avila O, Vélez N, Escandón P. Cryptococcosis in Dogs: A Case Report in a Labrador retriever in Bogotá, Colombia. Med Mycol Open Access. 2015, 1:4. doi: 10.21767/2471-8521.100004

8. Perfect JR, Bicanic T. Cryptococcosis Diagnosis and Treatment: What Do We Know Now. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015; 78: 49?54.

9. Tangeman L, Davignon D, Patel R, et al. Abdominal Cryptococcosis in Two Dogs: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 51(2):107-13.