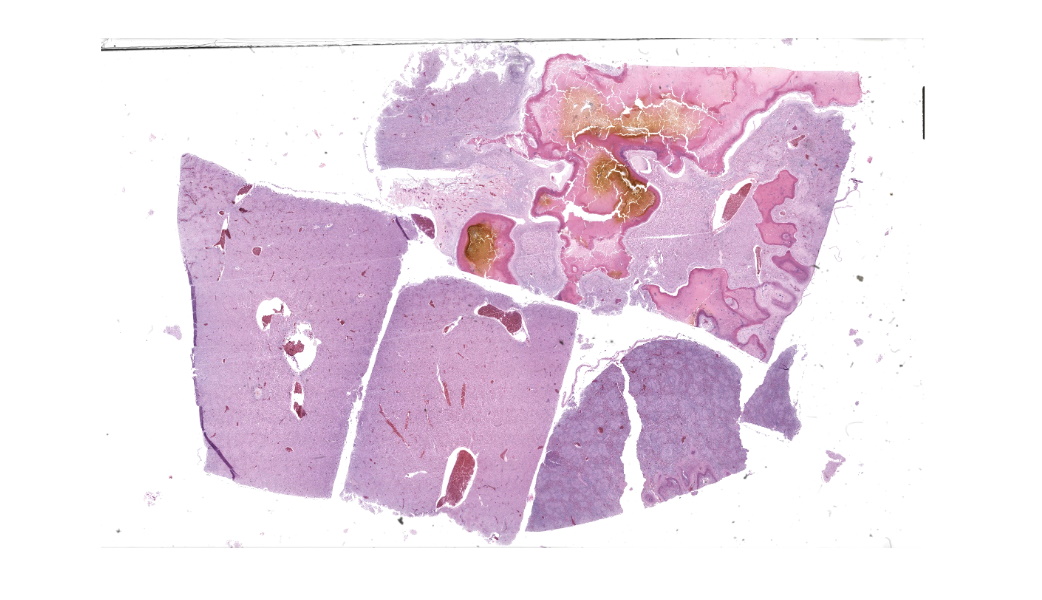

Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 11, Case 1

Signalment:

1-year-old, female, Brahma chicken (Gallus gallus)History:

Gross Pathology: The hen was covered in innumerable presumed mites. The heart had multifocal to coalescing regions of pallor. The liver had multifocal to coalescing regions of pallor with a focus of yellow, caseous material surrounded by green discoloration on the left lobe. The kidneys bilaterally had multifocal to coalescing regions of pallor.Laboratory Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture of the liver: Enterococcus faecalisTwort’s Tissue Gram Stain: Cocci were gram-positive.

Microscopic Description:

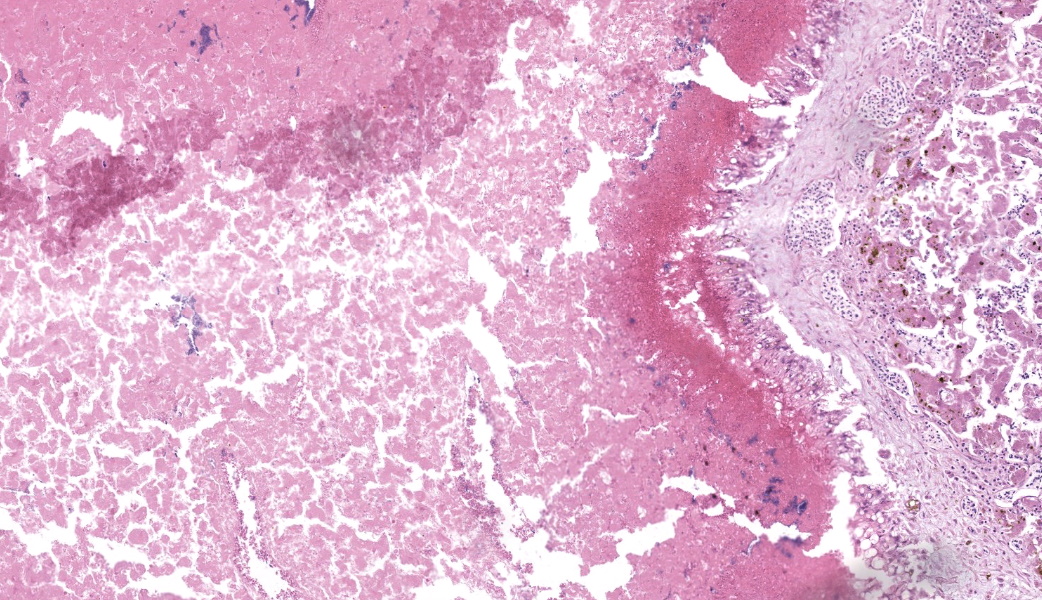

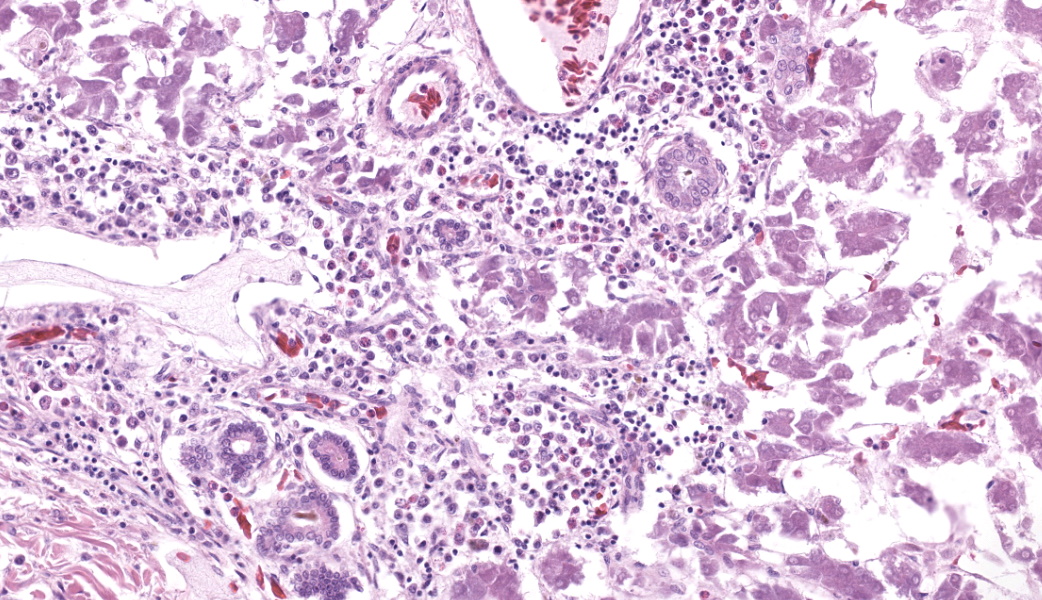

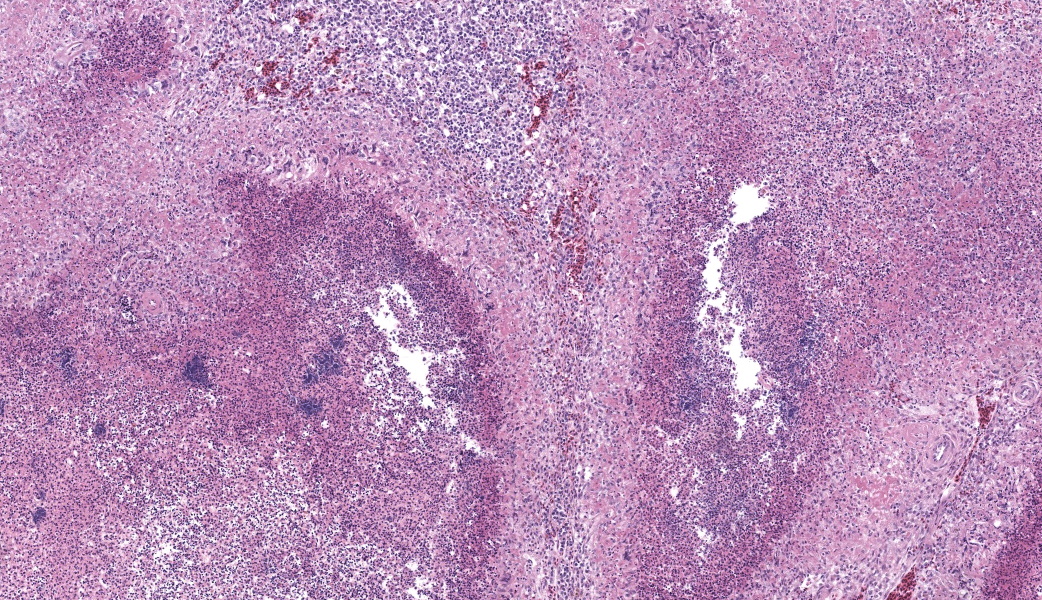

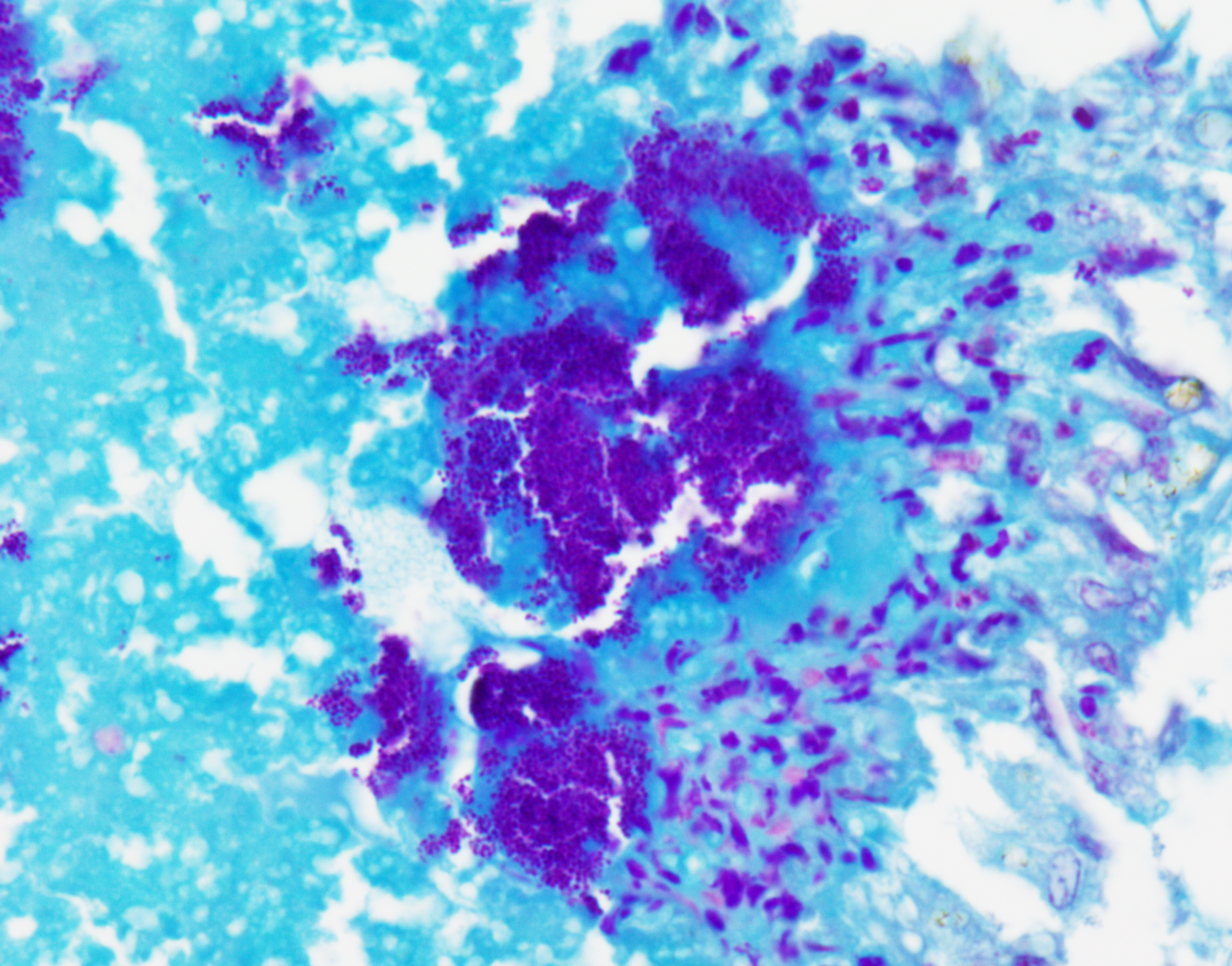

Liver: Three sections of liver are examined. Within one section, there are multiple and coalescent, irregularly shaped granulomas replacing up to 60% of the tissue, multifocally blending in with the fibrous connective tissue of portal areas. Granulomas center around hypereosinophilic necrotic material mixed with relatively low to medium numbers of degenerate heterophils and cellular debris and multiple clusters of coccoid bacteria. Bordering the necrotic center is a layer of palisading macrophages with abundant eosinophilic and frequently vacuolated cytoplasm (epithelioid macrophages) and occasional multinucleated giant cells, which are further outlined by a robust layer of fibroblasts and collagen. Portal areas are variably expanded by medium to high numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, including many laden with brown cytoplasmic granules, intermingled with numerous bile ducts (biliary hyperplasia), which extend into the adjacent parenchyma. In some portal areas, there are higher numbers of granulocytes with large, indented, vesiculate nuclei (interpreted as myeloid precursor cells and extramedullary hematopoiesis). Throughout all three sections of liver are individual necrotic hepatocytes to large regions of coagulative necrosis often centered around centrilobular veins, characterized by hepatocytes with shrunken, angular cell borders, hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and a pyknotic to karyorrhectic nucleus; larger areas of coagulative necrosis are frequently infiltrated by viable and non-viable heterophils. Within areas of necrosis and areas of viable hepatocytes are small clusters of coccoid bacteria within sinusoids.Spleen: The splenic parenchyma is interrupted by a few, relatively smaller, coalescing granulomas centered around numerous viable and non-viable heterophils, pyknotic nuclei and cellular and karyorrhectic debris, which is separated by a collar of collagen and macrophages with the occasional multinucleated giant cells. Within these regions, there are multifocal cocci bacteria colonies. There are deposits of fibrin and serum protein present throughout the sinuses and around ellipsoids. Within these foci are few reticuloendothelial cells, red cells, low numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as pyknotic nuclei and karyorrhectic and cellular debris and colonies of coccoid bacteria.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: granulomatous and necrotizing hepatitis, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with intralesional cocci and biliary hyperplasiaSpleen: granulomas, multifocal, marked, with intralesional and embolic cocci

Contributor's Comment:

Enterococci are non-motile, gram-positive, facultative anaerobic cocci bacteria that can appear in short and medium chains.6 Unlike staphylococci and streptococci, toxins are not produced. Surface components that allow success for Enterococci include a polysaccharide capsule, adhesins, pili, and aggregation substance. Enterococci are able to produce biofilms, which allows for adherence, especially in nosocomial infections and contributes to antibiotic resistance. Virulence factors include bacteriocins, hemolysins, gelatinases, and serine proteases. Cell injury has been induced via production of toxic oxygen metabolites.7 Unlike Streptococcus sp., these bacteria can tolerate bile salts and grow on MacConkey agar.9Enterococcus sp. are considered normal flora in the gastrointestinal tract of poultry and other bird.3,5,8 However, certain species that have been isolated in clinical disease include E. avium, E. cecorum, E. durans, E. faecalis, E. faecium, and E. hirae. Enterococcosis is a bacterial septicemia that has been reported in a variety of avian species. Birds can be afflicted via oral or aerosol routes (bedding, water, hatchery fluff) but can also arise from skin wounds.5,8 There have been reports of vertical transmission through hens with salpingitis or peritonitis that continue to lay.5 However, Enterococcus faecium has the potential to be a useful probiotic against other detrimental gastrointestinal disease in birds, such as colibacillosis, and improve feed efficiency.3,10

Across all ages, Enterococcus faecalis affects birds of all ages just as in this hen in this case, followed by faecium. Many birds die due to the rapid progression of disease and have vague clinical signs to include depression, lethargy, ruffled feathers, diarrhea, and decrease in egg production. Virulence factors that allow for infection include the collagen-binding protein (ace), aggregation substances (asa1), hemolysin activator (cylA), endocarditis antigen (efaA), surface protein (esp), gelatinase (gelE, and putative surface antigen EF0591.5

Enterococcus cecorum has become a significant disease in adult broiler chickens, causing femoral head necrosis, spondylitis, and arthritis. This disease is colloquially called “kinky back” when vertebral osteoarthritis occurs. The pathogenesis was recently described as requiring intestinal colonization that progressed to bacteriaemia prior to invading the skeletal tissue and demonstrated that intestinal disease itself was not required.1,2

In other species, Enterococci cause mastitis, enteritis, respiratory disease, endocarditis, and urinary tract disease as well as septicemia.9 In humans, Enterococci cause 12% of nosocomial infections with E. faecalis and faecium being the most prevalent of the species.6 Nosocomial infections frequently occurred through IV catheters, urinary catheters, aortic valve implantation, prosthetic joints, and other surgical sites. Occasionally, neurologic diseases, to include meningitis, do occur.7

Contributing Institution:

University of Connecticut Department of Pathobiology and Veterinary Sciences, Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratoryhttps://pathobiology.cahnr.uconn.edu/ https://cvmdl.uconn.edu/

JPC Diagnoses:

- Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, heterophilic and granulomatous, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with numerous cocci.

- Spleen: Splenitis, necrotizing, heterophilic and granulomatous, chronic, multifocal, moderate, with numerous cocci.

- Liver: Extramedullary hematopoiesis, chronic, periportal, moderate.

JPC Comment:

The University of Pennsylvania’s Dr. Nathan Helgert moderated this year’s 11th conference. This is his first time moderating for the WSC, and participants thoroughly enjoyed his quick wit and engaged teaching style. He chose to focus on poultry and ruminant pathology, which participants are always grateful for. This first case was a classic entity with fantastic histologic lesions that, according to some conference goers, provided the perfect moment to make use of the term “geographic” to describe those dramatic areas of necrosis. They truly resemble some beautiful cartography.Conference discussion focused on the diagnostic approach to cases like this one where additional diagnostics are required to “suss out” the etiologic agent. Participants were asked to take a figurative step back and develop a list of possible causes of bacterial sepsis in chickens that could lead to hepatic and splenic lesions like these. The list included E. coli (colibacillosis), Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp, Streptococcus spp.,Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (although this is more likely in turkeys and pheasants than in chickens), Mycobacterium spp (especially M. avium), and Pasteurella multocida, to name just a few. Some of these look nearly identical to one another both grossly and histologically, while others of these have more distinct features. Either way, culture and special stains will be needed.

As with every case of suspected bacterial infection, a simple Gram stain can provide crucial information. Of these above-mentioned organisms, several of them are gram-negative rods, which would make them less likely with the gram-positive staining seen in this case. Mycobacterium spp, which are best revealed with acid-fast stains due to the mycolic acid in their cell wall, were not present in this case. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is a gram-positive rod, but the bacteria in this case were clearly cocci. Although it can sometimes be challenging to discern bacterial morphology, participants felt confident in this case calling these cocci both on the H&E and on the gram stain. This narrowed the field substantially to Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, or Enterococcus. The contributor was able to culture Enterococcus faecalis from an aerobic bacterial culture to confirm the identity of the offending organism in this case.

The contributor provides a succinct overview of Enterococcus spp in poultry, including the virulence factors that enable their pathogenesis. Infection by Enterococcus spp in chickens (and other birds) is considered opportunistic, and affected birds are generally older (>12wks) than those affected by E.coli, which typically affects younger birds. Enterococcus faecalis is normal flora of the chicken GI tract, whereas Enterococcus cecorum, which still requires intestinal colonization to occur prior to septicemic spread, is not.4,5E. cecorum has a known predilection for bone, and primary sites of bone infection include the free thoracic vertebra (the synsacrum), the femoral head, and the hock.2

So why the free thoracic vertebrae? Predilection of E. cecorum for this site has been linked to osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD) of the free thoracic vertebrae, which is a common background lesion in broiler chickens.2,4 The current hypothesis is that these OCD lesions result in clefts in the articular cartilage within these vertebrae that facilitate E. cecorum colonization and subsequent vertebral osteomyelitis.2 Bacterial infection of bone results in a marked inflammatory response, coupled with edema and suppuration secondary to the actions of neutrophils and macrophages that are called in by pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, there is subsequent osteoclast activation and bone resorption, which can result in pathologic fracture and collapse of the affected vertebrae.2 This is one of the most common sequelae of this condition.2,4 Following fracture, there is dorsal displacement of suppurative material and necrotic bone into the spinal canal, resulting in a sudden onset of ataxia and loss of proprioception to the hind limbs. Affected chickens will have a classic “motorcycle rider” or “hock-sitting” stance due to their inability to use their legs.1,2.4 These birds will also have dirty wing edges due to “wing-walking” behavior as they attempt to ambulate with the support of their wings.

If you aren’t sure what this “motorcycle rider” stance looks like in Entercoccus-infected birds, please do not google “motorcycle rider chicken” without the addition of “Enterococcus” unless you want to see photoshopped images of chickens riding actual motorcycles, or unless you want to learn all about “chicken strips” in the motorcycle community, which refer to the unworn rubber on the outer edges of motorcycle tires. They are called “chicken strips” because they are usually seen on bikes of riders that are considered too nervous, or "chicken", to lean their bike over in sharp turns. Speaking from experience, being able to lean your bike over so far in a turn that you “get your knee down” to the pavement is considered to be an important rite of passage for motorcyclists, but one would have to imagine that chickens do not appreciate this comparison (MAJ C. Culligan, personal communication).

References:

- Borst LB, Jung A, Chen LR, Suyemoto MM, Barnes, HJ. A Review of Enterococcus cecorum infection in Poultry. Avian Dis. 2018; 62: 261-271.

- Borst LB, Suyemoto MM, Sarsour AH, et al. Pathogenesis of Enterococcal Spondylitis Caused by Enterococcus cecorum in Broiler Chickens. Vet Path. 2017; 54: 61-73.

- Cao GT, et al. Effects of a probiotic, Enterococcus faecium, on growth performance, intestinal morphology, immune response, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coliPoult Sci. 2013; 92(11): 2949-2955.

- Dolka B, Chrobak-Chmiel D, Czopowicz M, Szeleszczuk P. Characterization of pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum from different poultry groups: Broiler chickens, layers, turkeys, and waterfowl. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185199.

- Jorgensen SL, et al. Characterization of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from the cloaca of fancy breeds and confined chickens. J Appl Microbiol. 2017; 122: 1149-1158.

- Rehman MA, Yin X, Zaheer R, et al. Genotypes and Phenotypes of Enterococci Isolated from Broiler Chickens. Front Sustain Food Sys. 2018; 2: 1-28.

- Said MS, Tirthani E, Lesho E. Enterococcus Infections. Treasure Island, FL; Stat Pearls [Internet]; 2022: 1-33

- In: Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Carter, ME, Donnelly WJ, Leonard FC. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. London, UK; Blackwell Science Ltd; 2002: 49-51.

- The Genera Streptococcus and Enterococcus. In: Songer JG, Post KW. Veterinary Microbiology: Bacterial and Fungal Agents of Animal Disease. 1st St. Louis, MO; Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 51-53.

- Zheng A, Luo J, Meng K, Li J, Bryden WL, Chang W, Zhang S, Wang LX, Liu G, Yao B. Probiotic (Enterococcus faecium) induced responses of the hepatic proteome improves metabolic efficiency of broiler chickens (Gallus gallus). BMC Genomics. 2016;17:89.