Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 9

30 October 2019

Frederic Hoerr, DVM, MS, PhD

Veterinary Diagnostic Pathology, LLC

638 South Fort

Valley Road

Fort Valley, Virginia, 22652 USA

CASE IV: S699/14 (JPC 4085966).

Signalment: Hessian crop pigeon, juvenile (< 1 year), weight: 440 g, female

History: The examined animal came from a private breeding livestock. Several pigeons died without any clinical symptoms. Treatment was not applied.

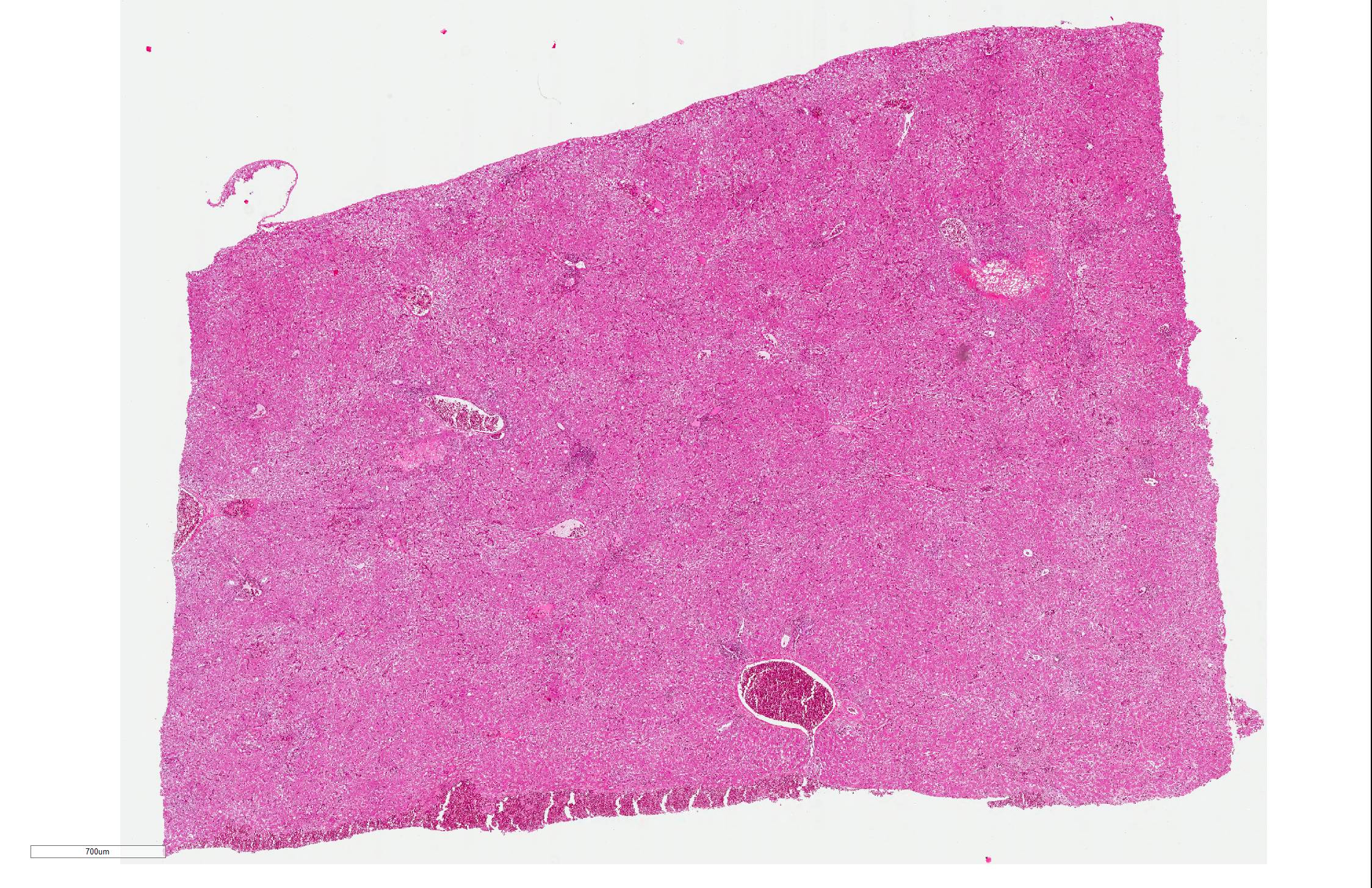

Gross Pathology: Both liver and kidneys showed multifocal beige to dark-brown colored foci, in diameter 0.2-0.3 mm, extending to subjacent parenchyma. In the lungs multifocal moderate acute hemorrhages were diagnosed. The pigeon was in good body condition.

Laboratory results: Molecular biological examination:

PCR for Pigeon Herpesvirus (PiHV): positive

PCR for Pigeon Circovirus (PiCV): positive

Parasitological examination:

Detection of a small number of coccidial oocysts

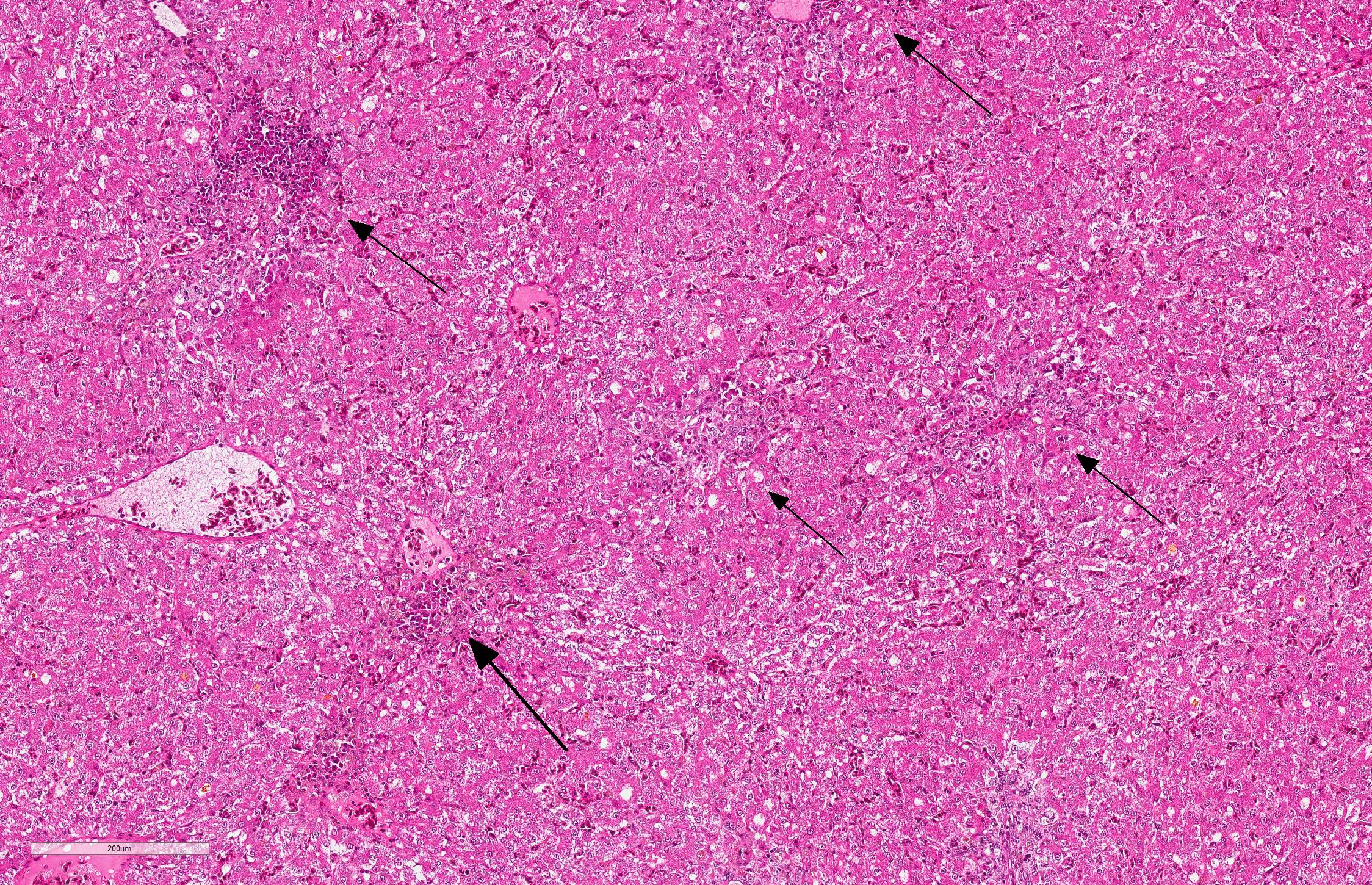

Microscopic Description:

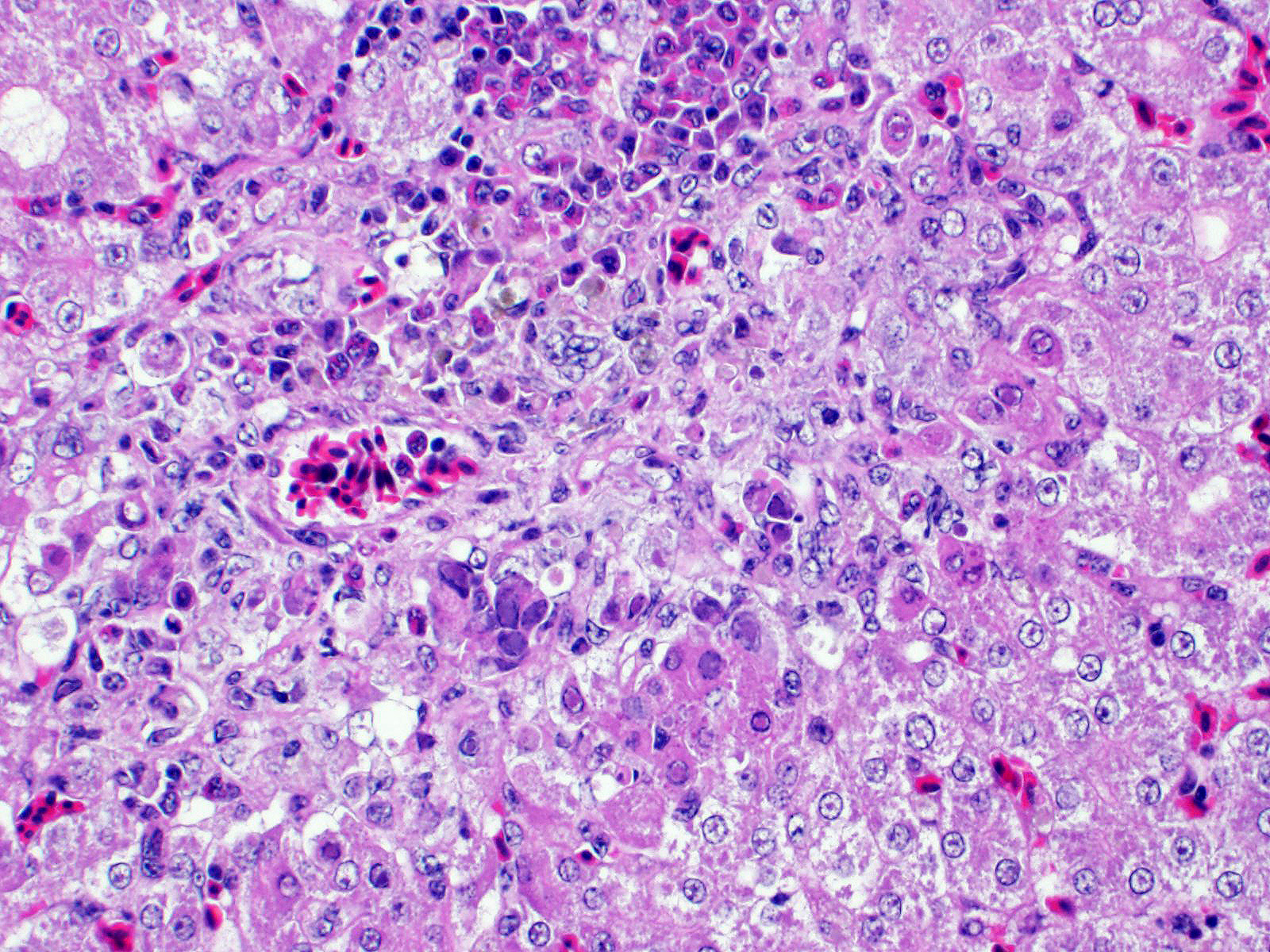

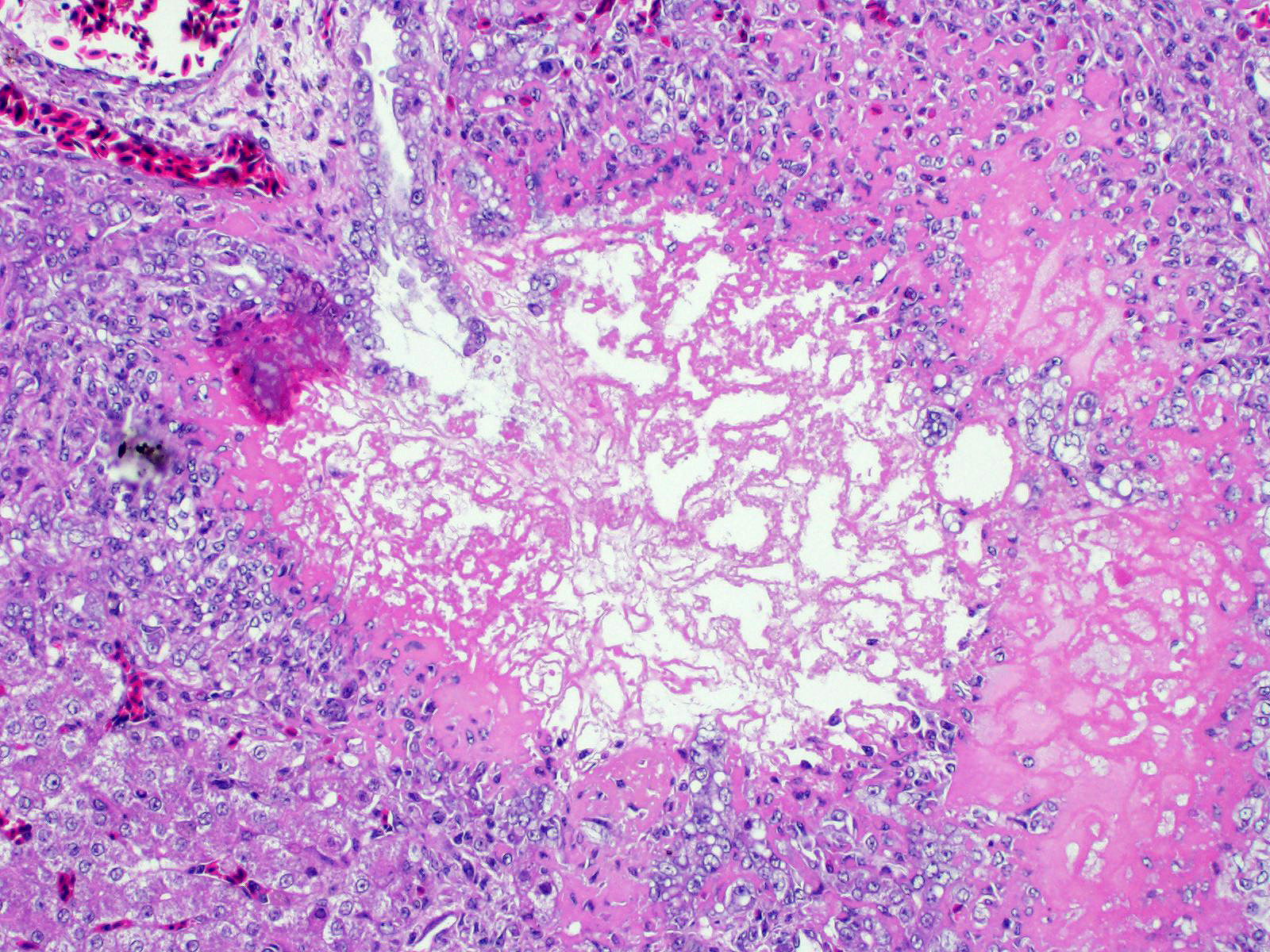

Liver: There are multifocal areas of acute necrosis, in some areas associated to the portal fields. These areas are demarcated by a moderate infiltration with predominantly histiocytes/macrophages, some lymphocytes and a few neutrophils and plasma cells and a very mild beginning fibrosis. In numerous intralesional hepatocytes large (5-10 µm) amphophilic to basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies type Cowdry A can be detected. Partly these large inclusions possibly seem to be located in the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes as well. Furthermore numerous hepatocytes show intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies (ca. 3 µm) type Cowdry B. There is a diffuse moderate irregularity and dissociation of the cords of hepatocytes with a diffuse moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis of the hepatocytes. Multifocal a mid-zonal to peripheral lobular localized degeneration of hepatocytes is detected. In the periphery of areas of necrosis a few round and lightly basophilic structures (councilman-bodies) can be noticed.

With reference to the portal fields a mild to moderate hyperplasia of bile ducts and a very mild interstitial fibrosis with fibroplasia is obvious. Additionally, in the cytoplasm of several hepatocytes and Kupffer cells a small amount of light brown to green and of golden-yellow to light green fine and coarse granules is detected, most likely consistent with a mild hemosiderosis and a mild storage of bile pigment. Diffuse moderate hyperemia and multifocal mild acute hemorrhages are obvious.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: hepatitis, necrotizing and histiocytic/granulomatous, multifocal, polyphasic, moderate with numerous intranuclear inclusion bodies.

Contributor Comment: Circoviruses are very small (15-20 nm in diameter) non-enveloped icosahedral viruses with circular single-stranded DNA. Because of their small size circoviruses are dependent on cellular enzymes of the host for their replication. Therefore, tissues with rapid cell proliferation, such as lymphoid tissue, are affected by circovirus.2,7 Beside the pigeon circovirus (PiCV) three other circoviruses are known to be infectious pathogens of spontaneous diseases. Chicken anemia virus (CAV) in fowl, which has been reclassified in the genus Gyrovirus, psittacine beak and feather disease (PBFD) in psittacine birds and porcine circovirus (PCV) in pigs.4

The PiCV was first identified in the USA but since it has been reported in many European countries, in North America, Australia and South Africa, probably a worldwide distribution is assumed. The practice of the pigeon sports probably supported the worldwide spread of the virus.2

Typically PiCV infects, as in the present case, young pigeons under one year of age. The way of transmission is not fully understood yet, but most infections seem to occur an oral way. Additionally, an egg-transmitted infection is also to be taken in consideration.5

Clinical signs can be lethargy, growth retardation, poor race performance and various symptoms caused by secondary bacterial or parasitic infections induced by immunosuppression. In contrast to PBFD a dystrophy and loss of feathery or beak deformations can only be seen rarely in PiCV infections. PiCV is normally associated with high morbidity and varying mortality, depending on secondary infections. In necropsy gross findings are usually very rare, atrophy of the bursa of Fabricius can occur. Other lesions often result from the secondary infections. A common histopathological finding is necrotizing bursitis and large (up to 15µm) basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies in the cells of the lymphoid follicles. Rarely these inclusion bodies are seen in other organs, such as spleen, thymus and GALT/BALT.1,2,4,5 Definitive diagnosis can be made by PCR or in situ hybridisation. The Pi(CV) is found in the bursa of Fabricius, spleen, thymus, kidney, respiratory system and liver. As PiCV can be detected in clinically and histopathologically normal pigeons, many PiCV infections seem to be subclinical.5

The young pigeon disease syndrome (YPDS, swollen gut syndrome) is a multifactorial disease in young pigeons, aged from 4 to 12 weeks. Its etiological agent(s) is (are) still unknown. The PiCV plays an important role in YPDS by inducing immunosuppression. Other possibly involved infectious agents are pigeon herpesvirus, pigeon adenovirus, avian polyomavirus and bacterial pathogens such as Spironucleus columbae and Escherichia coli.5

Herpesviruses are large (180-250 µm in diameter) enveloped viruses with double-stranded DNA and an icosahedral capsid. Their replication occurs within the nucleus of the host cell.

Pigeon herpesvirus-1 (PiHV-1) has a worldwide distribution. Pigeons are the natural hosts of PiHV-1, in which it remains latent. Adult pigeons are asymptomatic carriers. Squabs are infected very early in life by latently infected pigeons feeding the squabs with cropmilk. The squabs are protected if they received maternal antibodies conferred with egg yolk. These pigeons also become asymptomatic carriers. In case the egg yolk does not contain any maternal antibodies, the emerging squabs are fully susceptible for PiHV-1 infection and develop clinical symptoms.

Adult pigeons (latent carriers) often appear completely healthy, although PiHV-1 can be isolated from the pharynx of these birds. Susceptible young birds develop clinical symptoms. In necropsy retarded development and pharyngitis, partly associated with small foci of necrosis and small ulcers are observed. In generalized infections the histopathological examination reveals necrosis in the liver and the spleen. Intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatocytes are common findings.

Infection with Trichomonas gallinae, Chlamydia spp. or avian paramyxovirus should be considered as differential diagnoses.

Serological examinations (in positive cases) can only provide information about the infection state of the animal. Diagnosis of PiHV-1 infection should be confirmed by virus isolation.3,9

Contributing Institution:

Institut für Veterinär-Pathologie, Veterinärmedizinische Fakultät Leipzig, Universität Leipzig, Germany (http://www.vetmed.uni-leipzig.de/ik/wpathologie)

JPC Diagnosis Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal, random, subacute, with small bascophilic and large basophilic intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment: The contributor does an excellent job

at describing two common viral infections in pigeons, only one of which can be

diagnosed by examining this particular slide.

Like most alphaherpesviruses, the course of herpesviral

disease is most often subclinical in the natural host, but may cause

significant damage is other species. In the pigeon, most infections are

latent, but may recrudesce in times of stress or concurrent disease. In

Belgium, 50% of pigeons have antibodies to the virus; when affected with other

respiratory pathogens, PHV-1 can be isolated in the pharynx of up to 80% of

birds.4 In adult birds, clinical disease is limited to the

respiratory tract with necrotizing lesions in the mouth, pharynx and larynx;

superficial bacterial lesion results in more severe lesions.9

Necrotizing hepatitis is most often seen in young birds which did not receive

maternal immunity through the egg yolk, making this an intriguing potential

cause of "young pigeon disease syndrome".

The disease in pigeons, is eclipsed by the disease in owls and falcons who have

preyed upon infected pigeons. PCR studies have demonstrated that the

herpesvirus that causes "hepatosplenitis infectiosa strigum" or

"hepatosplenitis" in raptors is identical to columbid-herpesvirus 1, once again

illustrating the severe disease which often results when alphaherpesviruses

jump into aberrant hosts. For more information on the disease in raptors, see

the following WSC cases - WSC 2017-2018 Conf 15 Case 1, WSC 2014-2015 Conferenc

13, case 4, WSC 2010-2011, Conference 8, Case 1.

Pigeon circovirus (PiCV) was first diagnosed in Canada in 1986, and shortly after, was diagnosed in many countries around the world. In recent studies, infection rates in flocks range averaged around between 75 and 80% in China and Europe, with similar rates in healthy and unhealthy birds. 6 The potential transmission of this disease in racing birds as well as cosmopolitan pigeons is extremely high. While mortality in affected flocks in two-month- to 1-year-old pigeons may be up to 100%9, the potential of circoviruses to cause lymphoid necrosis and immunosuppression in affected birds may be even more profound.9

"Young pigeon disease syndrome", (YPDS) as mentioned by the contributor, is a syndrome of disease which appears closely interrelated with the immunosuppressive effects of pigeon circovirus, much like the many syndromes associated with porcine circovirus-2. It was first described in the 1980s, and affects birds from 4-12 weeks of age, resulting in anorexia, ruffled feathers, regurgitation and diarrhea, excessive crop liquid, and polyuria. In affected flocks, morbidity approaches 20% and mortality 50%. As the contributor has stated, a variety of infectious agents, in addition to PiCV have been incriminated, to include pigeon adenoviruses and herpesviruses. A recent study of birds with YPDS in Poland demonstrated a 44.5-100% infection rate with PiCV, and the second most common viruses in affected birds was pigeon herpesvirus-1, at approximately 30%.7 Pigeon adenovirus was not identified in any flocks in this study.

The characteristic botryoid basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions of pigeon circovirus are largely restricted to lymphoid tissues, and would not likely be seen within hepatocytes in this case, although there was great variation in size and shape of the inclusions in this case. While the age of this bird may or may not be consistent with the syndrome of YPDS, and the evidence is circumstantial at best, it is interesting to ponder the effects of PiCV in generating clinical systemic herpesviral disease in a mature bird.

References:

1. Abadie J, Nguyen F, Groizeleau C, Amenna N, Fernandez B, Guereaud C, Guigand L, Robart P, Lefebvre B, Wyers M: Pigeon circovirus infection: Pathological observations and suggested pathogenesis. Avian Pathology. 2001; 30(2): 149-158

2. Duchatel JP, Szeleszcuk P: Young pigeon disease. Medycyna Wet. 2011; 67(5): 291-294

3. Kaleta EF Herpesvirus der Tauben. In: Kaleta EF and Krautwald-Junghanns M-E ed. Kompendium der Ziervogelkrankheiten. Hannover: Schlütersche GmbH & Co. KG Verlag und Druckerei; 1999; 292-294

4. Marlier D, Vindevogel H: Viral infections in pigeons. The veterinary journal. 2006; 172: 40-51

5. Raue R, Schmidt V, Freick m, Reinhardt B, Johne R, Kamphausen L, Kaleta EF, Müller H, Krautwald-Junghanns M-E: A disease complex associated with pigeon circovirus infection, young pigeon disease syndrome. Avian Pathology. 2005; 34(5): 418-425

6. Stenzel TA, Pestka D, Tyklowski B, Smialek M, Knocicki A. Epidemiological investigation of selected pigeon viral infections in Poland. Vet Rec

7. Todd T: Circoviruses: immunosuppressive threats to avian species. Avian Pathology. 2000; 29: 373-394

8. Todd T: Avian circovirus diseases: lessons for the study of PMWS. Veterinary Microbiology. 2004; 98: 169-174

9. Vindevogel H, Duchatel JP. Pigeon Herpesvirus Infection. In: Calnek BW, Barnes HJ, Beard CW, Reid WM, Yoder Jr. HW ed. Diseases of Poultry. Ninth Edition. Ames: Wolfe Publishing Ltd; 1991; 665-667