WSC Conference 13, Case 1

Signalment:

3-year-old intact male, Chinese-origin cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis)

History:

This cynomolgus macaque from a maintenance colony at a contract research organization presented for ptosis of the left eye (OS). Physical exam additionally identified mydriasis, exophthalmos, abnormal retropulsion, and ophthalmoplegia OS. Direct pupillary light reflex (PLR) was absent OS, and consensual PLR was normal in the right eye (OD); direct PLR was normal OD, and consensual PLR was absent OS. The diagnosed ophthalmoplegia OS was refractive to medical treatment, and euthanasia was elected.

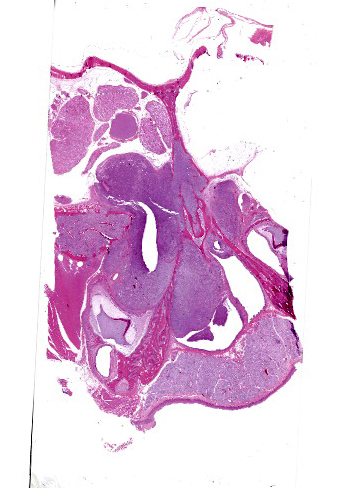

Gross Pathology:

The left orbit was pale yellow. There was a firm, yellow-tan mass filling the left caudal sinuses and displacing the nasal turbinates and adjacent bone, including the orbit and ventral cranium. The ventral cranial vault was focally displaced ventrally, and there was malacia of the adjacent left temporal brain.

Microscopic Description:

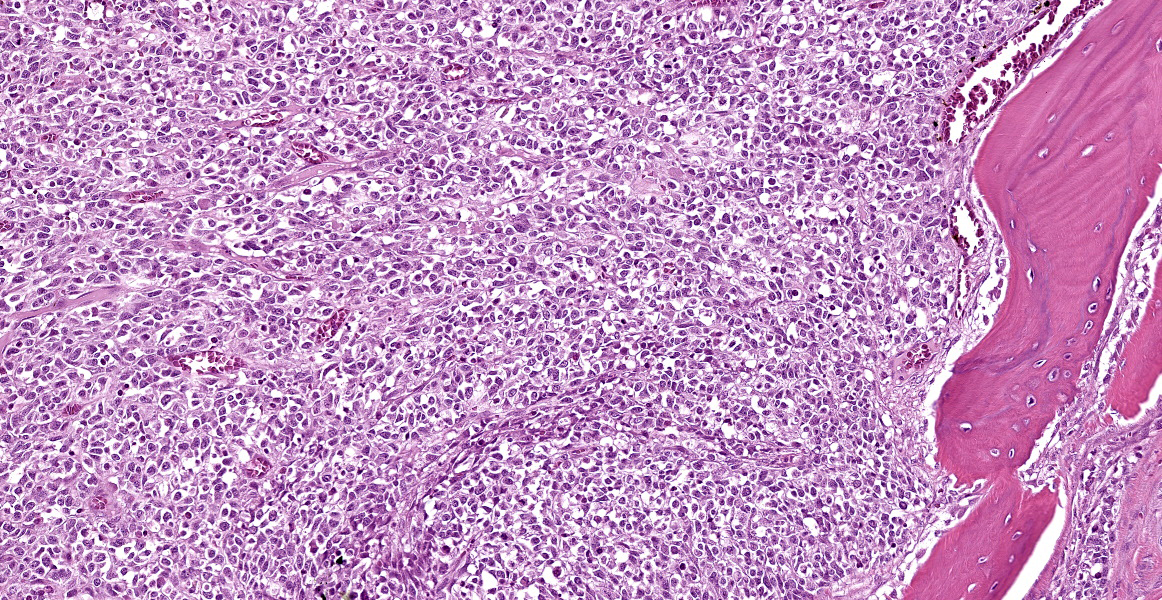

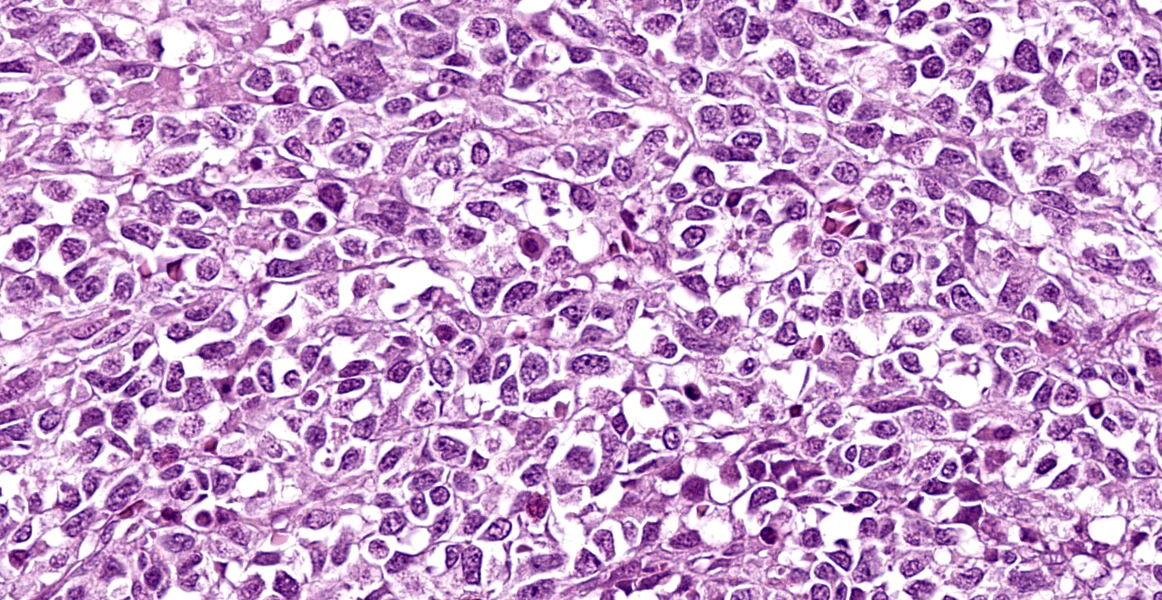

Arising from the nasal turbinates and infiltrating the nasal turbinates, skeletal muscle, and surrounding bone is a densely cellular, poorly circumscribed proliferation of neoplastic cells. Neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and packets that are supported by fine fibrovascular stroma. These cells are polygonal to spindloid, have variably distinct cell borders, and contain a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are ovoid to reniform, have coarsely stippled chromatin, and frequently contain 1-2 prominent nucleoli. Anisokaryosis is moderate and there are 1-3 mitoses per high power field. In areas where the neoplasm extends to the overlying squamous epithelium, there is erosion and ulceration with associated hemorrhage, inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, and abundant coccoid bacteria. Neoplastic cells were not present in sections of ocular or periocular tissue, although there was degeneration and regeneration of the extraocular skeletal muscle. There is destruction of cortical and woven bone, with replacement by neoplastic cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Nasal turbinates: Esthesioneuroblastoma (Olfactory neuroblastoma).

Contributor’s Comment:

Esthesioneuroblastomas are malignant neoplasms that appear histologically similar to neuroendocrine tumors. They arise from the neuroectoderm of the olfactory mucosa along the superior nasal vault. Esthesioneuroblastomas have been reported in humans, dogs, cats, horses, cows, mice, axolotls, and fish; however, they are rarely reported in cynomolgus macaques. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the second report of an esthesioneuroblastoma in a cynomolgus macaque.

In the horse, literature describes neoplastic cells labelling for antibodies against neurofilament protein, synaptophysin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, neuron-specific enolase, microtube-associated protein, and S-100 protein. Microtubule-associated protein (MAP-2) has been reported to label positively in the dog, cat, and horse; however, due to the lack of specificity of immunohistochemical markers, definitive diagnosis is made by visualizing cell processes that contain microtubule neurofilaments on transmission electron microscopy. Dense core neurosecretory granules are also visualized on TEM. These neoplasms are locally aggressive and often invade through the cribriform plate and into the sinuses and brain.

Contributing Institution:

Pathology Department

Charles River Laboratories – Mattawan

www.crl.com

JPC Diagnosis:

Nasal cavity and maxilla: Malignant neoplasm.

JPC Comment:

Esthesioneuroblastomas, also known as olfactory neuroblastomas (ONBs), are characterized histologically by epithelioid neoplastic cells with indistinct borders and scant cytoplasm that are often separated by neurofibrillary material. Rosette formation is a characteristic feature.2 ONBs are presumed to originate from olfactory epithelium and most tumors are located in the caudal nasal cavity in close proximity to the cribriformplate.5 ONBs are typically invasive, leading to osteolysis of facial structures, deformation of the ethmoturbinates, and invasion into the cerebral cortex.2,5

Human ONBs are evaluated using a four-tiered grading scheme and case reports in veterinary medicine tend to apply this scheme to animal ONBs, though it isn’t clear that this grading predicts biologic behavior in animals.1,5 Under this rubric, grade I ONBs exhibit lobular architecture, minimal nuclear pleomorphism, prominent neurofibrillary matrix, rosette formation, no mitotic figures or necrosis, and variable amount of calcification. By contrast, grade IV ONBs have variable amounts of lobular architecture, marked nuclear pleomorphism, absent neurofibrillary matrix, occasional rosette formation, marked mitoses, prominent necrosis, and no calcification.1

This week’s conference was moderated by Dr. Derron Alves, Chief of the Infectious Disease Pathogensis Section at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Conference discussion began with a review of the microscopic anatomy of the nasal cavity and surrounding structures and the types of epithelium present in the nasal cavity.

Conference discussion focused on the seeming mismatch between the histologic appearance of ONB described in the literature and the appearance of the neoplasm on the examined slide. Participants noted the complete lack of rosette formation, the lack of neurofibrillary matrix, and the presence of respiratory epithelium with no identifiable olfactory epithelium within the examined section. An attempt was made to match the tumor to the described Grade IV ONB histomorphology, but the lack of necrosis and rosette formation did not pass the smell test. Immunohistochemical results were similarly vexing, with neoplastic cells negative, or the stains non-contributory, for the following immunohistochemical markers: NSE, NeuN, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD3, CD20, CD138, pancytokeratin, and vimentin.

Participants had a wide range of differential diagnoses for this enigmantic tumor, including lymphoma, plasma cell tumor, round cell tumor, ONB, adenocarcinoma, and non-productive osteosarcoma. While most partipants agreed that the tumor was malignant based on the significant invasion and bony remodeling, participants felt that the histomorphology present in this section made ONB unlikely. The moderator proposed a differential diagnosis of “undifferentiated tumor, high grade,” which was as specific as participants were willing to get without further investigation.

This case was referred for post-conference consultation to the soft tissue and oral and maxillofacial MD pathologists at the Joint Pathology Center, who agreed that the morphologic characteristics of the tumor were inconsistent with human ONB. They proposed an additional battery of immunohistochemical stains, to include CD45rb, desmin, ERG, MUC-1, S-100, and smooth muscle actin, to sniff out the cell of origin. These stains were performed; however the vast majority of immunohistochemical stains performed on this neoplasm were non-contributory due to inappropriate behavior of internal controls, making our immunohistochemical results, in the main, unreliable.

After multiple external consultations and a plethora of unhelpful immunohistochemistry, conference participants remained unable to ascribe a cell of origin to this inscrutable neoplasm and preferred a somewhat on-the-nose morphologic diagnosis of “malignant neoplasm.”

References:

- Brosinski K, Janik D, Polkinghorne A, von Bomhard W, Schmahl W. Olfactory neuroblastoma in dogs and cats – a histological and immunohistochemical analysis. J Comp Path. 2012;146:152-159.

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier;2016:479.

- Lubojemska A, Borejko M, Czapiewski P, et al. Of mice and men: olfactory neuroblastoma among animals and humans. Vet Comp Oncol. 2014,13:70-82.

- Meuten, DJ. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Iowa State Press;2016:473-474.

- Siudak K, Klingler M, Schmidt MJ, Herden C. Metastasizing Esthesioneuroblastoma in a Dog. Veterinary Pathology. 2015;52(4):692-695.