Signalment:

Gross Description:

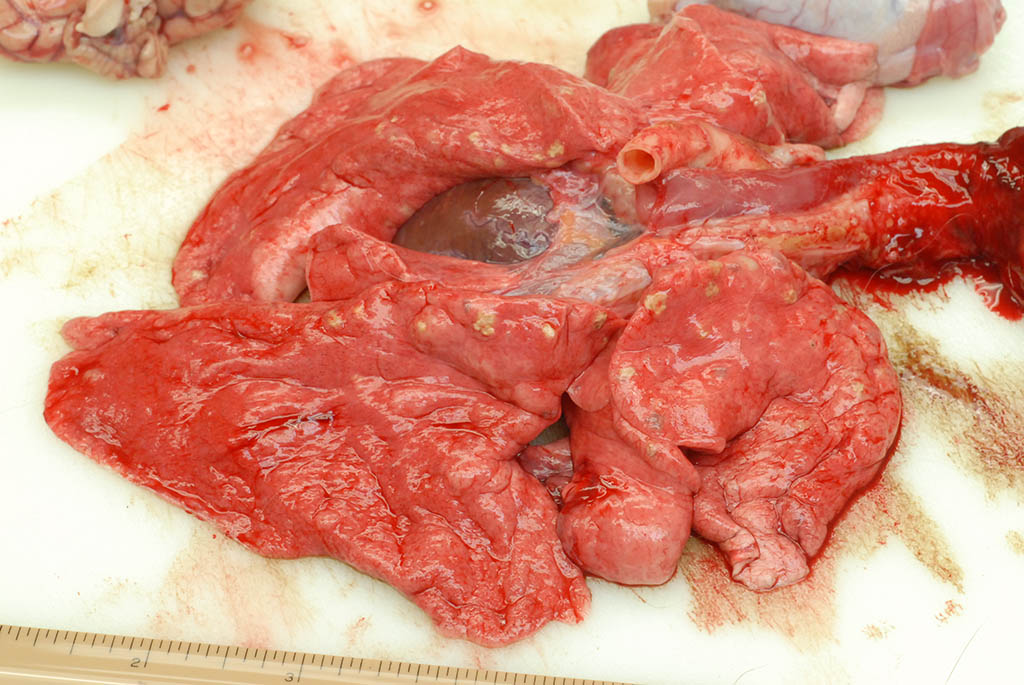

Internal: The liver was enlarged with pale tan edges on several lobes. The colon was distended with fluid feces. There was multifocal, 2-5 mm diameter, slightly raised tan nodules in all lung lobes.

Histopathologic Description:

Lung, rhesus macaque. Numerous 2-5mm diameter tan nodules are present within all lung lobes. (Photo courtesy of: Covance Laboratories, Inc, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

As demonstrated in the accompanying photographs, gross findings appear as multifocal and coalescing, discrete, irregularly round to ovoid, slightly raised, light brown foci several millimeters in size. In contrast to M. tuberculosis, the lesions of Pneumonyssus simicola are typically soft and cystic, or air-filled bullae.1 Thin fibrous adhesions within the pleural cavity are commonly observed.9

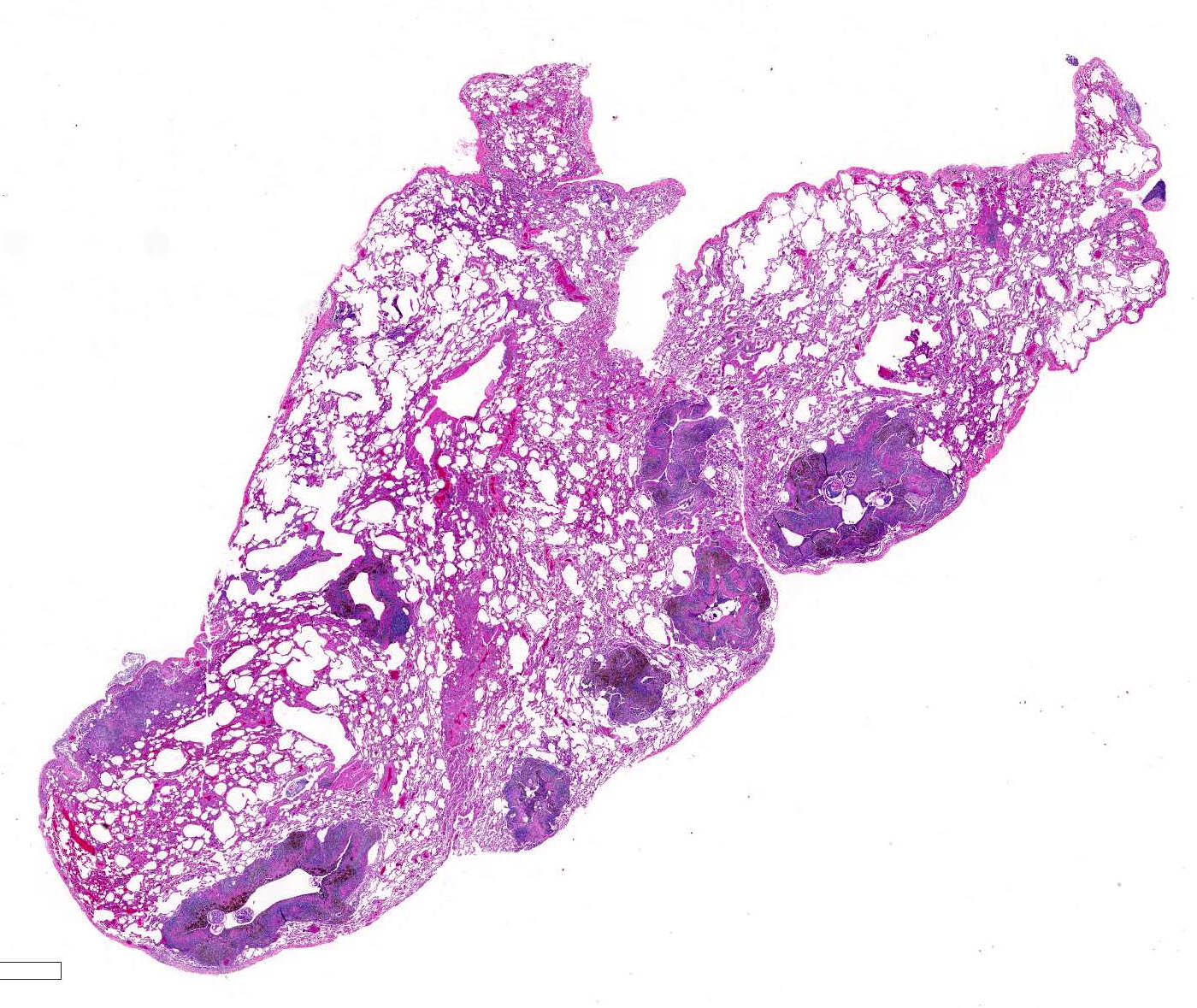

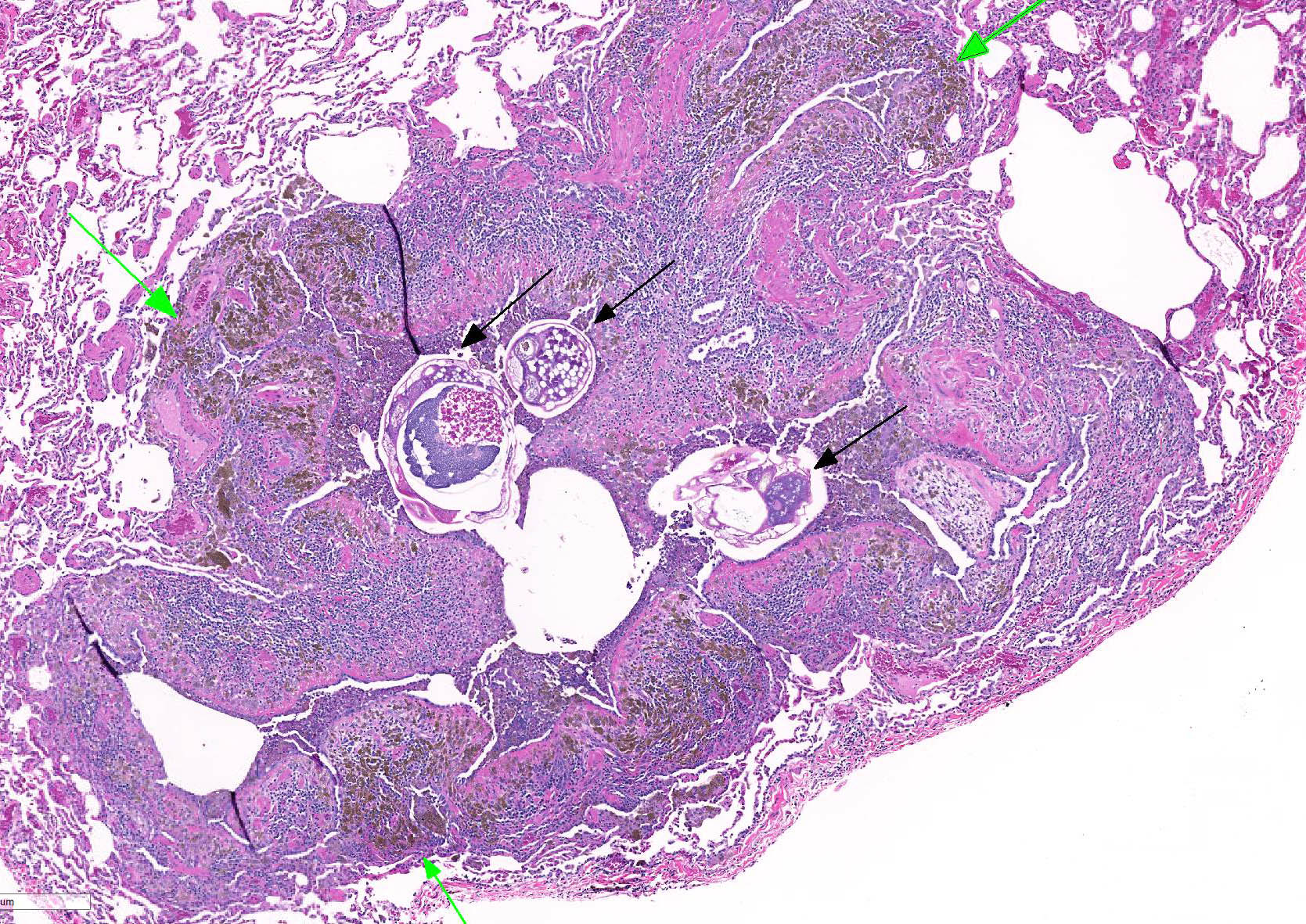

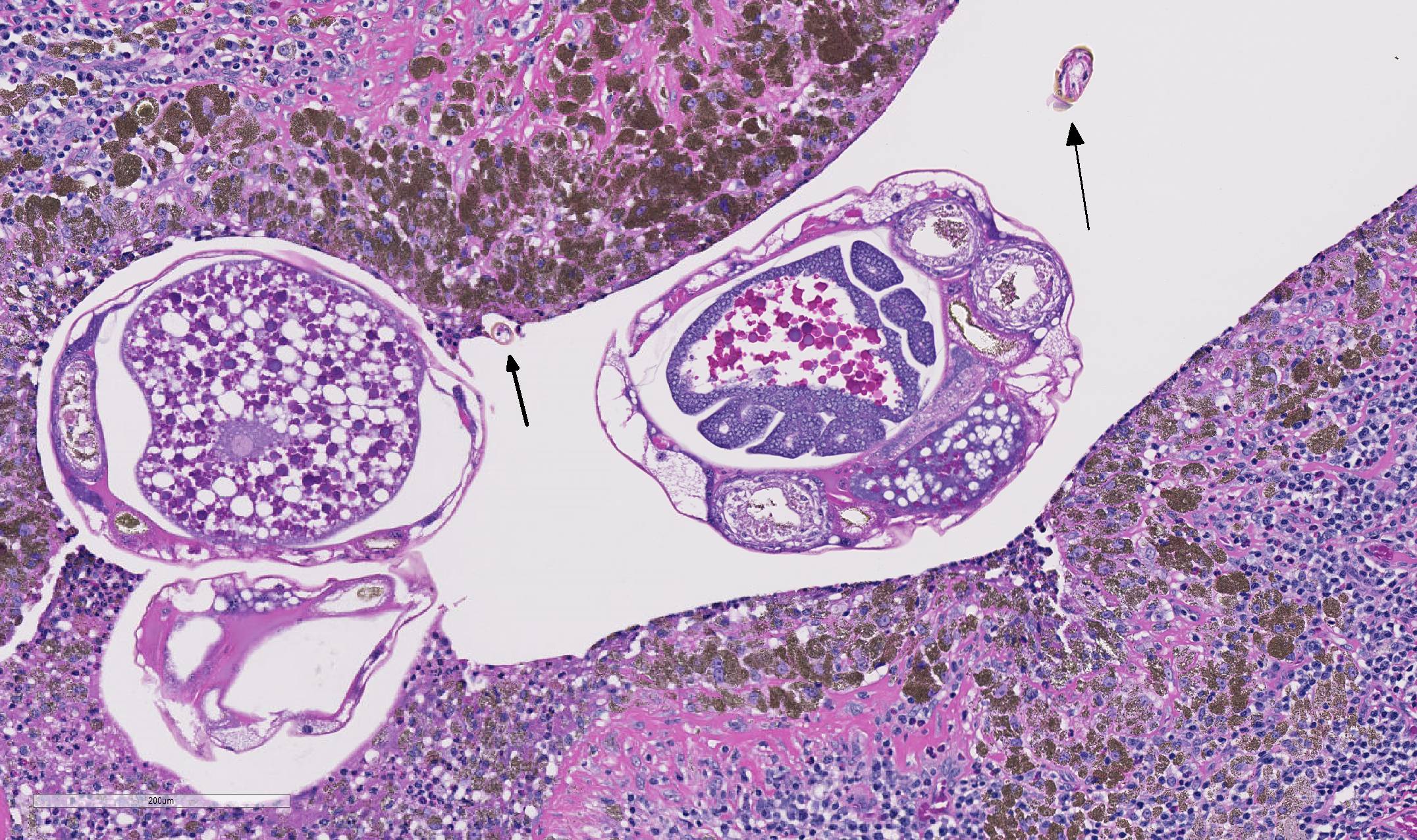

Microscopic lesions consist of multifocal chronic bronchiolitis and bronchiolectasis with hyperplasia of bronchiolar smooth muscle and prominent peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates admixed with eosinophils and pigment-laden macrophages. Adult mites, most of which are females, are normally evident in sections of affected lung. Mites are identifiable by typical arthropod characteristics; a chitinized outer cuticle, body cavity, striated musculature, jointed appendages, and sometimes other structures including brain, gastrointestinal and reproductive tract, eggs and occasionally larvae. The presence of birefringent brown to black pigment in macrophages at the periphery of affected bronchioles is a hallmark of infection and considered diagnostic even in the absence of identifiable mites.8

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

As described by the contributor, adult mites have the typical arthropod characteristics of 300-500 um width, chitinous exoskeleton, mouth parts, jointed appendages, striated musculature, a body cavity, digestive tract, reproductive structures, yolk material in yolk glands, and developing eggs.3

The highly characteristic birefringent golden brown to black crystalline mite pigment, thought to be a metabolite of digestion and excretion by the female mite, can be present in sections that lack mites and are diagnostic for the parasite.2,3,9 This pigment does not contain melanin or carbon, but rather is composed predominantly of iron. This the result of the mite feeding on host erythrocytes with digestion and excretion of blood protein, hemoglobin.9 Additionally, mite pigment is likely the cause of the majority of the inflammatory response within the lungs.2

Widespread use of the anthelmintic medication, ivermectin, during quarantine of new animals and as a part of routine colony management has markedly reduced the incidence in laboratory nonhuman primates.2,9

Pulmonary acariasis and nasopharyngeal mites occur in many other animal species. Some of the most important nasal and pneumotropic arthropod parasites of veterinary importance include Pneumo-nyssoides sp. in the lungs of New-world primates; Rhinophaga sp. in the nasal cavity of Old-world primates; Pneumo-nyssoides caninum, the nasal mite in dogs; Linguatula serrata in the nasal cavity of dogs and cats; Oestrus ovis, the nasal botfly in sheep and goats; Entonyssus sp. and Entophionyssus sp. in the trachea and lung of snakes; Cephenemyia sp. in the nasal cavity of wild cervids; Cytodites nudus in the air sacs of poultry; and Halarachne halichoeri in the nasal passages of wild sea lions.6

References:

1. Andrade MCR, Marchevsky RS. Histopathologic findings of pulmonary acariasis in a rhesus monkeys breeding unit. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária. 2007; 16(4):229-234.

2. Cogswell F. Parasites of non-human primates. In: Baker DG, ed. Flynns Parasites of Laboratory Animals. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:716-717.

3. Gardiner CH, Poyton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1999:56-58.

4. Keeling M, Wolf R. Respiratory diseases. In: Bourne G, ed. The Rhesus Monkey, Volume II: Management, Reproduction, and Pathology. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1975:70-71.

5. Lowenstine LJ, Osborn KG. Respiratory system diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee C, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. London, UK: Academic Press; 2012:467-468.

6. Pneumonyssus simicola. Joint Pathology Center Systemic Pathology (updated Oct. 2014). Retrieved from: https://www.askjpc.org/vspo/show_page.php?id=595.

7. Purcell JE, Philipp MT. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates: In Wolfe-Coote S, ed. The Laboratory Primate. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2005:589-590.

8. Stookey J, Moe J. The respiratory system. In: Benirschke K, Garner F, Jones T, eds. Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1978:106-107.

9. Strait K, Else JG, Eberhard ML. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardiff S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. San Diego, CA: Academic Press;