Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 13, Case 1

Signalment:

20-year-old, male, African lion, Panthera leo, Felidae.

History:

This lion had a clinical picture characterized by mild bleeding in the oral cavity, which lasted approximately for two weeks, and had been associated with an increase of the volume of the mandible. After this time, hemorrhagic episodes were observed sporadically.

Gross Pathology:

During the examination of the mandible, there was a firm, irregular mass, approximately 3.0 cm in length, with white areas interspersed with yellow foci located in the mandibula at the height of the lower left canine. Dental mobility of mandibular canines and a fracture of the mandibular bone, near to the mental protuberance were noted.

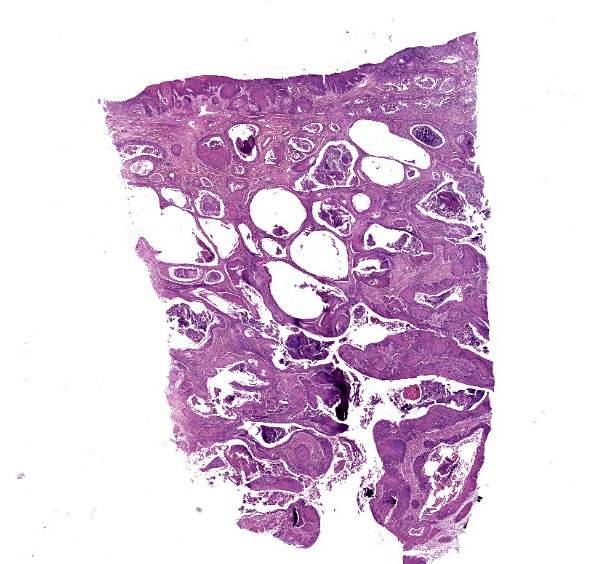

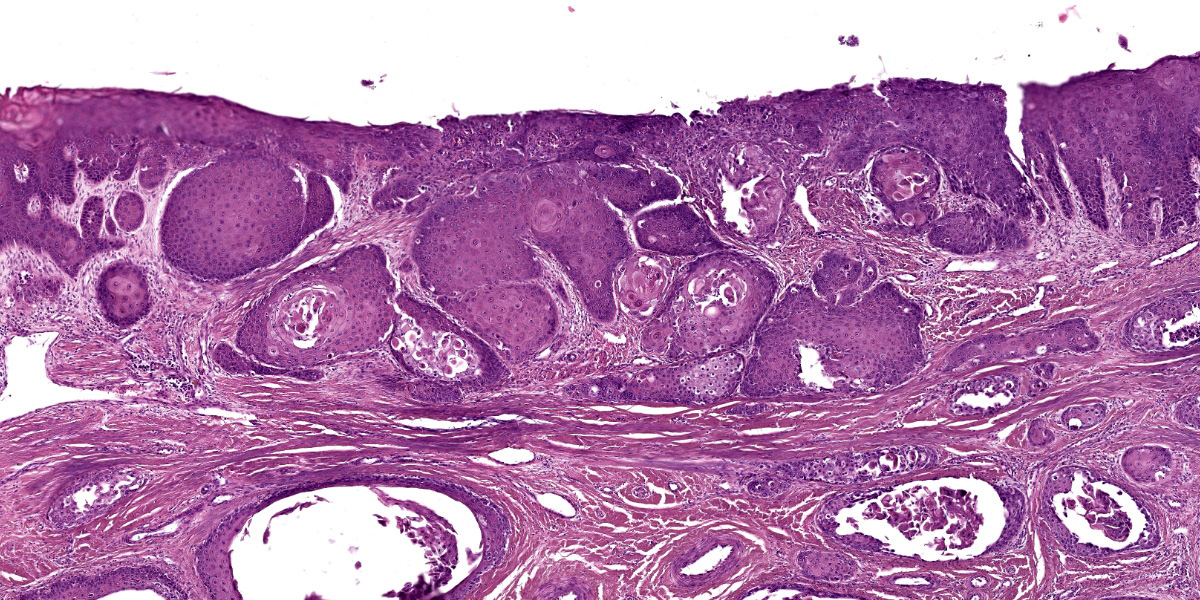

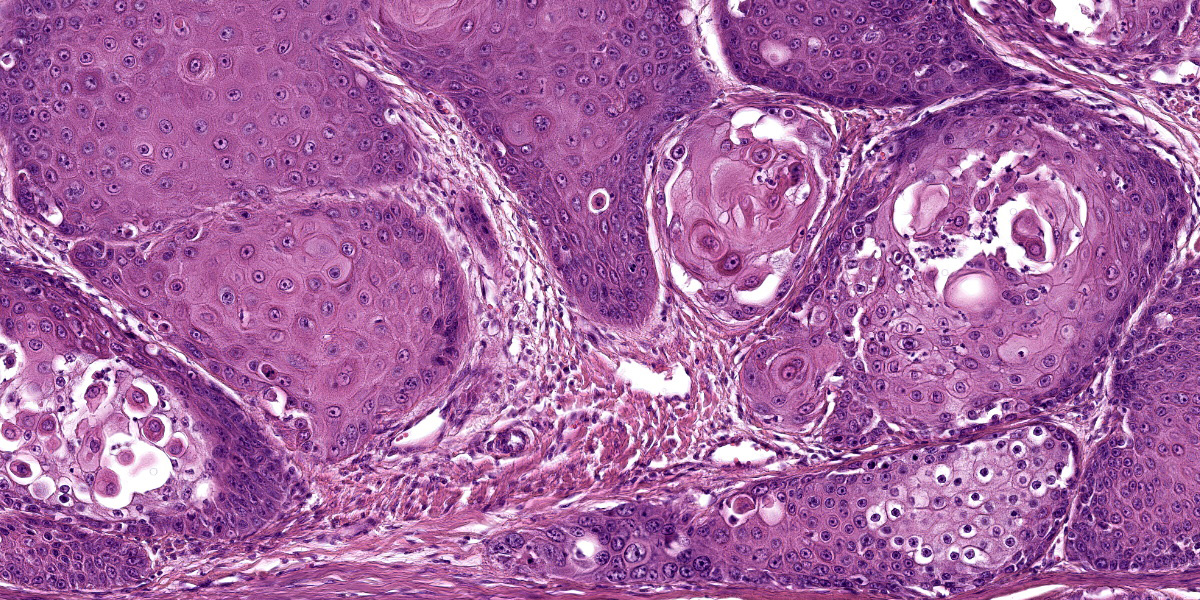

Microscopic Description:

Histopathology of the mandible revealed a non-encapsulated, expansive and infiltrative mass consisting of markedly pleomorphic keratinocytes, arranged either in mantles or in solid nests, supported by moderate to large fibrovascular stroma. In the center of some of these nests, deposition of lamellar eosinophilic material (keratin pearls) was noted and, occasionally, individual keratinocytes exhibited dyskeratosis. These cells have polygonal contours, moderate to broad cytoplasm, slightly eosinophilic, and round to oval vesicular nuclei with loose chromatin and 1 to 2 evident nucleoli. Moderate anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and multifocal areas of intratumoral necrosis are noted. Mitotic counts are 2-4 mitosis per higher magnification field (40X).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Contributor’s Comment:

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one of the main oral cavity tumors in domestic cats and may represent more than 60% of all oral tumors in this species.1 In wild felids however, its description is sporadic and current records include tumors affecting the oral cavity of lynxes and ocelots,2-4 the ear of leopards,5,6 the eyelid region of white tigers,7,8 the jaw of a Siberian tiger,9 and the leopard right hind limb.10 In Panthera sp. the diagnosis of SCC is better described in the snow leopard (P. uncia),11 in which cutaneous and oral SCCs can represent up to 9% of the causes of death.12

The high frequency of papillomas and oral SCCs associated with the isolation of papillomaviruses in P. uncia strengthens the hypothesis of the participation of viruses in the etiology of SCC in large felids.12,15,16,20 Other potential factors that may be related to carcinogenesis of oral SCC in these animals include pollution of urban centers9 as well previous dental diseases.17,18 In large felids, the upper and lower incisors seem to show a tendency for periodontal disease17,18 and are common sites of neoplasm growth in lions.9,19,20 It is important to highlight that the captive environment can influence the formation of calculi and periodontal diseases in tigers and lions as compared to free-living species,18 which can favor the formation of pre-neoplastic lesions.

The tongue and mandible seem to be important anatomical sites for SCCs in large felids, appearing as masses of rapid growth that are generally ulcerated and hemorrhagic with progressively infiltrative behavior. Microscopically, features such as the formation of keratin beads and individual keratinization of keratinocytes favored the diagnosis of SCC, considering that they are classic findings of neoplasia in well-differentiated to moderately-differentiated cases. Tumor expansiveness even favored bony lysis and cutaneous fistulation as identified in this case, whose clinical progression, degree of metastasis and evolution to death tend to be quite variable between species.

As there are few reports in the literature on wild felids, there is no definitive parameter on the survival time in cases of oral SCC in these animals. In domestic cats, neither the size of the mass nor its location in the mouth seem to be associated with survival time.21 Important differential diagnoses in lions include potential oral cavity tumors already reported in the species, such as peripheral odontogenic fibroma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the salivary gland, melanomas, hemangiosarcomas and fibrosarcomas.20,22-24

Contributing Institution:

Federal Rural University of Pernambuco

Laboratory of Animal Diagnosis

Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros

Dois Irmaos, Recife, 52171-900

Pernambuco, Brazil. www.ufrpe.br

JPC Diagnosis:

Mucosal surface (presumptive oral mucosa): Squamous cell carcinoma.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Major Anna Travis, JPC Chief of Education Operations who selected an eclectic group of cases for conference participants to consider.

The contributor nicely summarizes oral SCC and oral pathology in non-domestic felids, to include a number of helpful references for those interested in reading further on this topic. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral malignancy in all felids, including non-domestic ones.20 Other notable oral predilections include FEPLOs in lions, oral papillomas in snow leopards, and eosinophilic inflammation in tigers.20

SCC remains a frequent WSC submission across species – the case discussion focused on associated general pathology features common across species, including keratinization. Basal cells exhibit basophilia in part due to large numbers of free ribosomes producing keratin filaments (protein; tonofilaments) that give strength to the epidermal layer. In the stratum spinosum, an even greater proportion of tonofilaments are bundled to form tonofibrils that interface with a greater number of desmosomes which further enhances tissue strength.25 In the granular layer, keratohyalin granules containing profilaggrin serve to bind tonofibrils into larger macrofibrils. Squamous cells subsequently lose cellular organelles and nuclear contents as they transition to the stratum corneum.25 As such, SCC represents aberrancy of ordered keratinization as was evident in this case.

Conference participants discussed the exact location of this neoplasm as they lacked the terrific gross image for this case provided by the contributor. While the lack of adnexal units and presence of a non-keratinizing (lacking keratohyalin granules) epithelium were suggestive of the oral cavity, MAJ Travis reminded participants to also consider the pharynx, conjunctiva,esophagus, rectum, vulva, and even vagina as potential locations (although in felids, the oral mucosa is by far the most common location for this neoplasm).

References:

- Murphy BG, Bell CM, Soukup JW. Veterinary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 1st ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2020:143.

- Altamura G, Eleni C, Meoli R, et al. Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a European Lynx (Lynx Lynx): Papillomavirus Infection and Histologic Analysis. Vet Sci. 2018; 5(1):1.

- Sladakovic I, Burnum A, Blas-Machado U, et al. Mandibular squamous cell carcinoma in a bobcat (Lynx rufus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2016; 47(1): 370-373.

- Yanai T, Noda A, Murata K, et al. Lingual squamous cell carcinoma in an ocelot (Felix pardalis). Vet Rec. 2003; 152(21):656-657.

- Quintard B, Greunz EM, Lefaux B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in two snow leopards (Uncia uncia) with unusual auricular presentation. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2017; 48(2):578–580.

- Leme MCM, Martins AMCRPF, Bodini MES, et al. Carcinoma de células escamosas em uma jaguatirica (Leopardus pardalis). Arq Inst Biol. 2003; 70(2):217-219.

- Bose VSC, Nath I, Mohanty J, et al. Epidermoid carcinoma of the eyelid in a tiger (Panthera tigris). Zoos’ Print, 2002; 17:965-966.

- Gupta A, Jadav K, Nigam P, et al. Eyelid neoplasm in a White Tiger (Panthera tigris) - a case report. Vet Archiv. 2013; 83(1):115-124.

- Oliveira AR, Carvalho T, Arenales A, et al. Mandibular squamous cell carcinoma in a captive Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica). Braz J Vet Pathol. 2018; 11:97-101.

- Kesdangsakonwut S, Sanannu S, Rungsipipat A, et al. Well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Captive Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa). Thai J Vet Med. 2014; 44(1):153-157.

- Napier JE, Lund MS, Armstrong DL, et al. A retrospective study of morbidity and mortality in the North American amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) population in zoologic institutions from 1992 to 2014. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2018; 49(1):70–78.

- Joslin JO, Garner M, Collins D, et al. Viral papilloma and squamous cell carcinomas in snow leopards (Uncia uncia). American Association of Zoo Veterinarians and International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine Joint Conference, 2000: 155–158.

- Bertone ER, Snyder LA, Moore AS. Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Domestic Cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2003; 17(4):557-562.

- Munday JS, Howe L, French A, et al. Detection of papillomaviral DNA sequences in a feline oral squamous cell carcinoma. Res Vet Sci. 2009; 86(2): 359–361.

- Sundberg JP, Montali RJ, Bush R, et al. Papillomavirus-associated focal oral hyperplasia in wild and captive Asian lions (Panthera leo persica). J Zoo Wildl Med. 1996; 27(1):61–70.

- Terio KA, McAloose D, Mitchell E. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. 1st ed. Elsevier; 2018:263-285.

- Collados J, Garcia C, Soltero-Rivera M, et al. Dental Pathology of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus), Part II: Periodontal Disease, Tooth Resorption, and Oral Neoplasia. J Vet Dent. 2018; 35(3):209–216.

- Kapoor V, Antonelli T, Parkinson JA, et al. Oral health correlates of captivity. Res Vet Sci. 2016; 107:213-219.

- Castro MB, Barbeitas M, Borges T, et al. Fibromatous Epulis in a Captive Lion (Panthera leo). Braz J Vet Pathol. 2011; 4:150-152.

- Scott KL, Garner MM, Murphy BG, et al. Oral Lesions in Captive Nondomestic Felids With a Focus on Odontogenic Lesions. Vet Pathol. 2020; 57(6):880-884.

- Northrup NC, Selting KA, Rassnick KM, et al. Outcomes of cats with oral tumors treated with mandibulectomy: 42 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2006; 42(5):350-360.

- Junginger J, Hansmann F, Herder V, et al. Pathology in Captive Wild Felids at German Zoological Gardens. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6):e0130573.

- Kloft HM, Ramsay EC, Sula MM. Neoplasia in Captive Panthera Species. J Comp Pathol. 2019; 166:35-44.

- Steeil JC, Schumacher J, Baine K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of a dermal malignant melanoma in an African lion (Panthera leo). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2013; 44(3):721-727.

- Welle MM, Linder KE. The Integument. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:1095-1096.