Signalment:

Flock of 20,000 11-week-old commercial meat turkeys,

Meleagris

gallopavo.Flock experienced a spike in mortality.

Flock is housed in barn and bedded with a layer of shavings on top of dirt

floors. This is the first time this disease has been identified on this farm but

the producer does have a second farm where turkeys are also raised and this

disease has been a recurring problem on that farm.

Gross Description:

The submitting vet-erinarian described

swollen livers with yellow streaking and very enlarged dark spleens in the

turkeys that were necropsied. Birds also had unclotted blood in the abdominal

cavity.

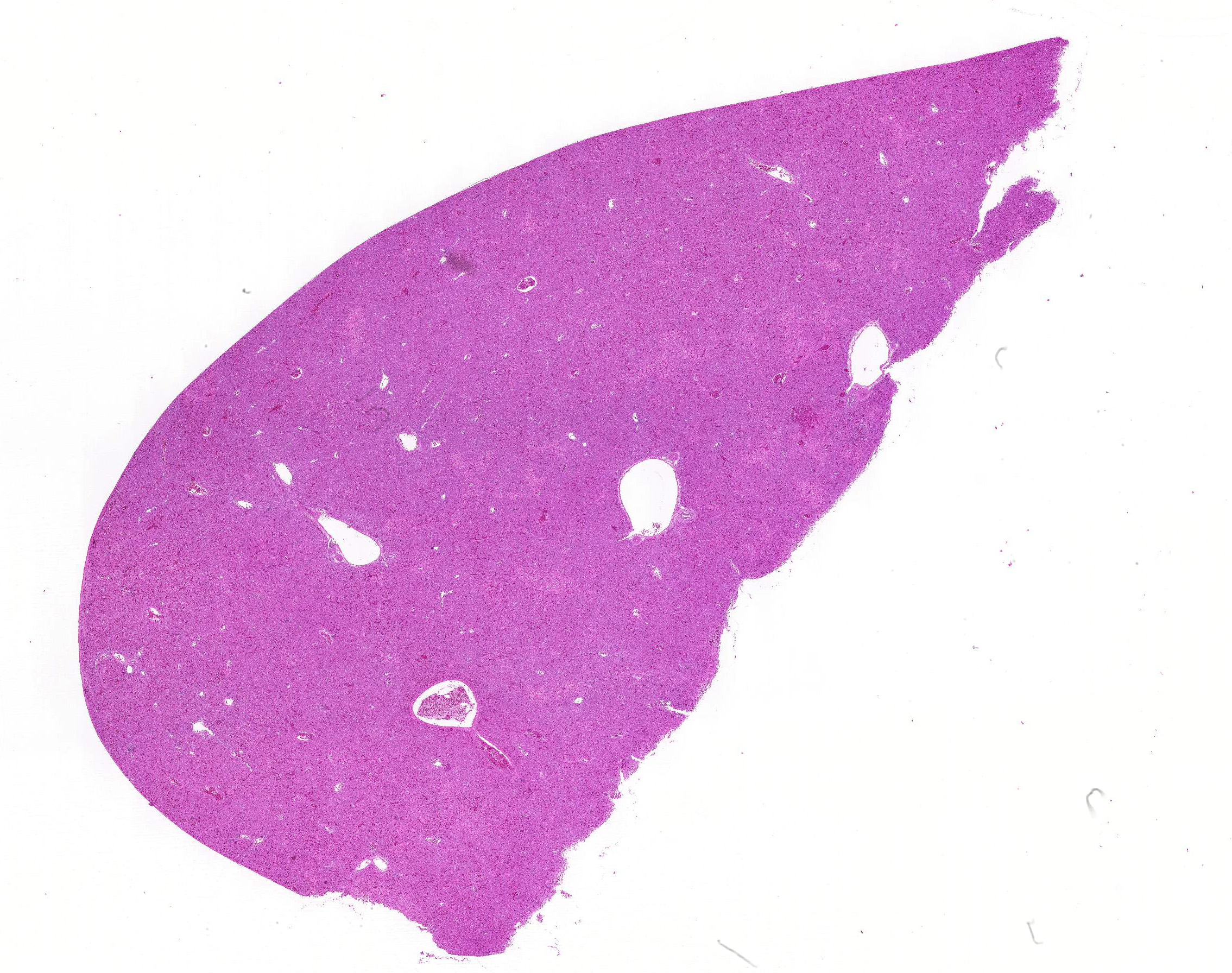

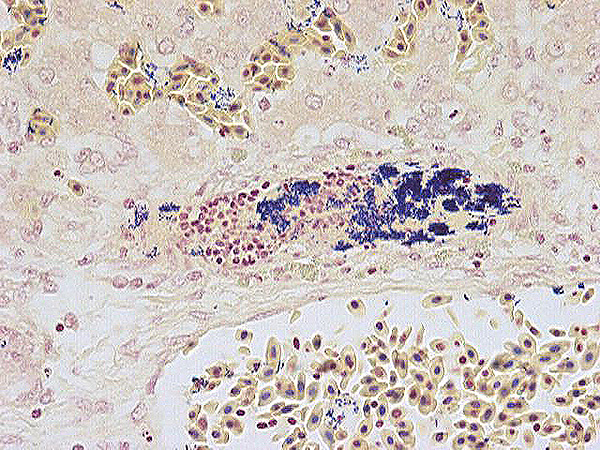

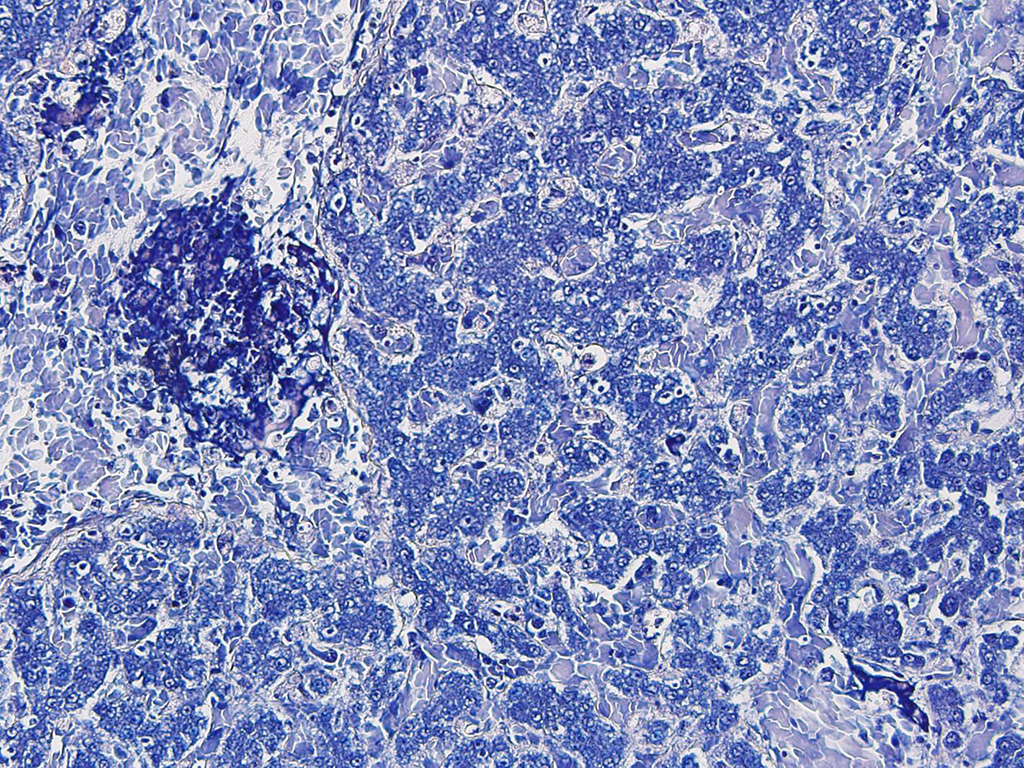

Histopathologic Description:

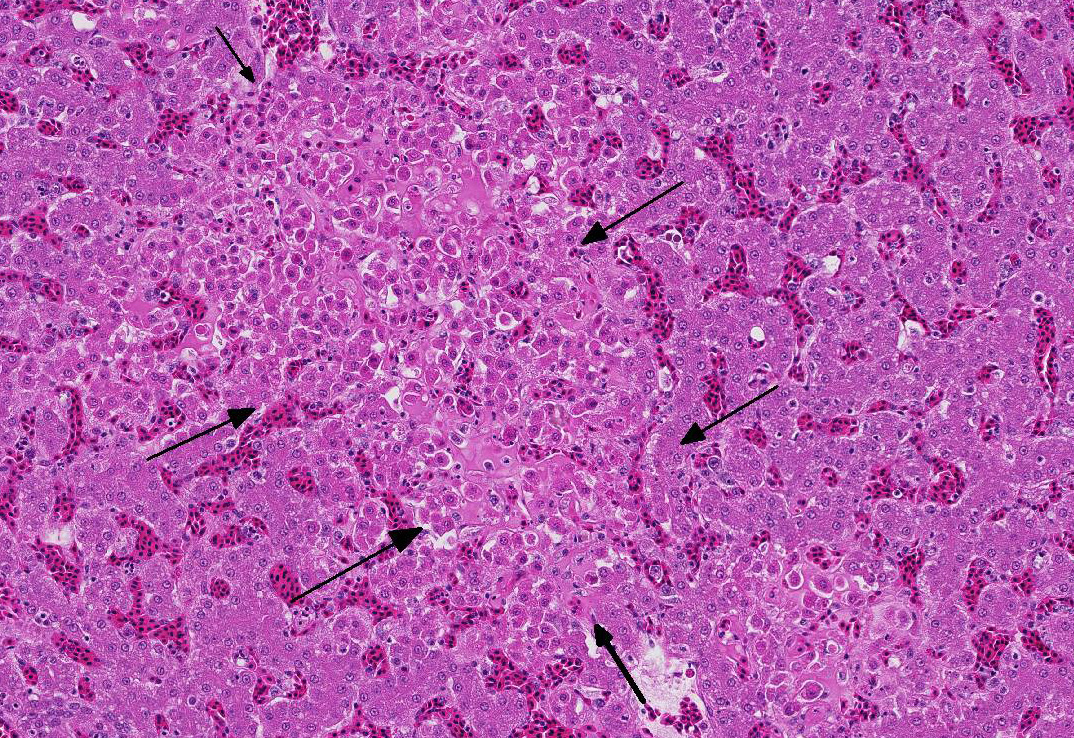

The liver is moderately congested. Multiple variably-sized foci of

hepatic necrosis, characterized by individualized, hy-pereosinophilic

hepatocytes with granular or shrunken, hyalinized cytoplasm and either lacking

nuclei or containing pyknotic or karyorhectic nuclei, are closely associated

with terminal hepatic veins. Hepatocytes surrounding these necrotic foci are

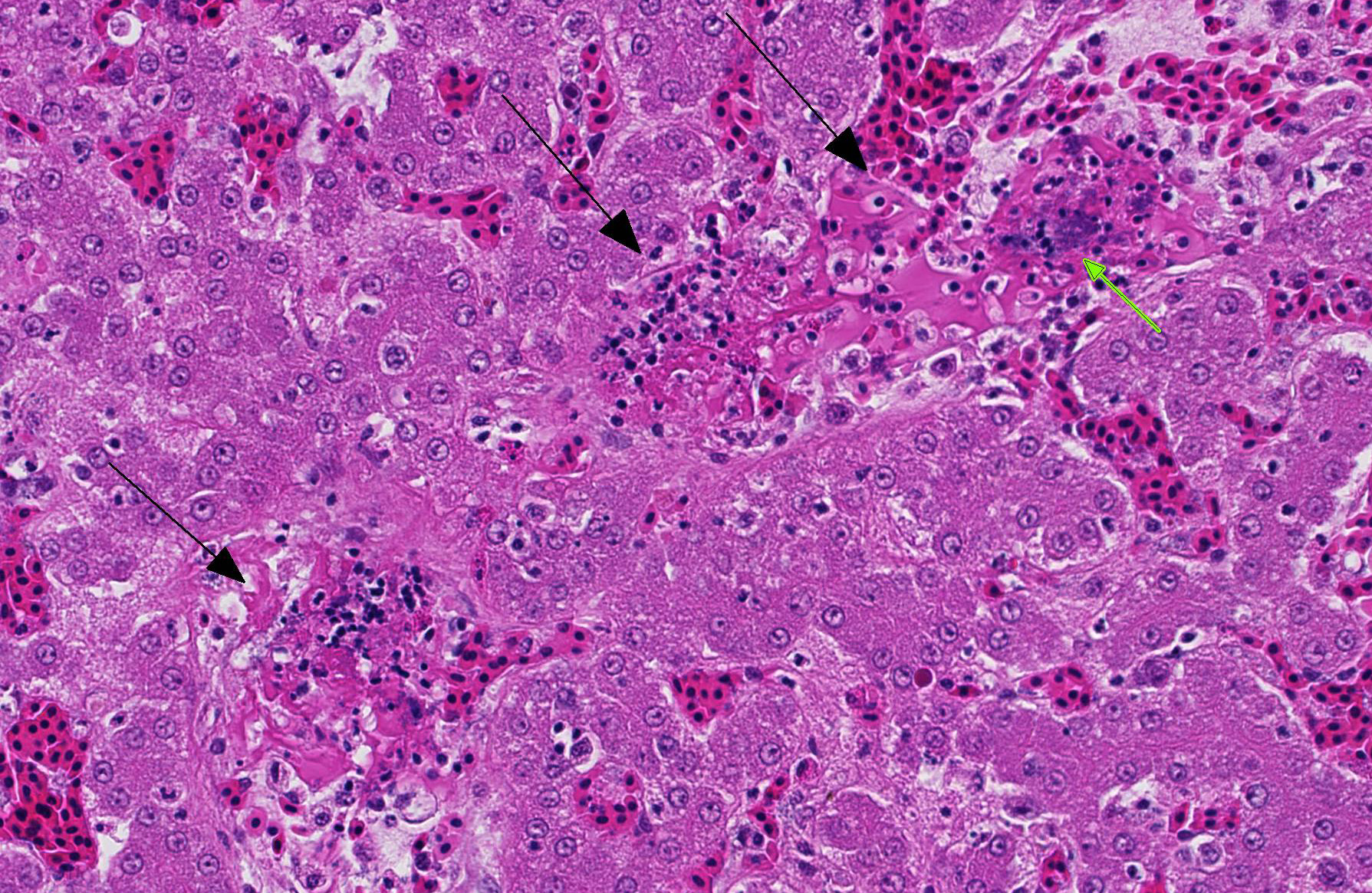

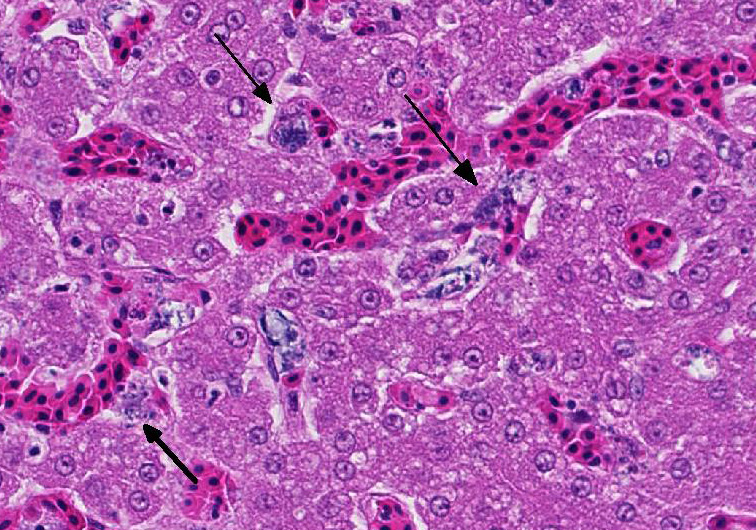

occasionally swollen with pale vacuolated cytoplasm. Multifocally, veins and

sinusoids and less frequently small arteries contain fibrin thrombi bearing mats of slender rod-shaped and sometimes

gently curved bacteria. Similar appearing bacteria are also free in sinusoids

and within activated Kupffer cells, which also contain pha-gocytized debris

including red blood cells. Occasionally the walls of veins and small arteries

containing fibrin thrombi have segmental necrosis, with some affected arteries

having intramural heterophils and rarely small amounts of nuclear debris.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Mild, acute, multifocal, hepatic necrosis with necrotizing

vasculitis and intravascular fibrin thrombi containing colonies of pleomorphic

rod-shaped bacteria.

Liver: Moderate hepatic congestion

Lab Results:

4+

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

was recovered from a swab of the internal organs.

Condition:

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathae

Contributor Comment:

Erysipelas

is an acute septicemic disease occurring most commonly in older male turkeys. The

differential diagnosis includes other gram-negative bacterial septicemias

caused by agents such as

E. coli,

Salmonella spp. or

Pasteurella

multocida.2 Histologically

, the pathology of an

Erysipelothrix

rh-usiopathiae infection is different from most gram-positive agents, first

because of the sheer numbers of bacteria present and secondly because of their

variable appearance, with slender rod-shaped to slightly curved bacteria

aggregating in mats within vessel and capillary lumens and entangled in

fibrinous thrombi. Because these bacteria are slow growing, a rapid

presumptive diagnosis can also be made by identification of clumps of

gram-positive slender straight or slightly curved rod-shaped bacteria from

organ or bone marrow smears.

2 This case was

submitted to the lab in early October which is typical for cases of erysipelas,

as outbreaks are reported to occur most often in the late fall or winter. It is

thought that the bacteria can persist in the soil and since many grow-out barns

for turkeys have dirt floors, the risk of repeat occurrences exists.

2

In this case, this farm has never experienced an outbreak of erysipelas but the

other farm has and it is suspected that there was mechanical transfer of the

bacterium from one farm to another. Penicillin is the

antibiotic of choice for treating erysipelas. Vaccination using a killed

bacterin is an option if the risk of infection is high.

2 In humans, the

infection caused by

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is known as

erysipeloid, a skin infection typically localized to fingers and hands and

usually preceded by an abrasion or cut. The lesion is actually a cellulitis and

is very painful. Systemic effects, such as septicemia and endocarditis can

occur but are uncommon.

6 Most cases of human infection are the

result of occupational exposure and those occupations at higher risk include

fish handlers, veterinarians, farmers, slaughter plant workers and butchers.

Some colloquial names for this condition include fish handler's disease, seal

finger and whale finger.

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, nec-rotizing, acute, multifocal, random, with septic fibrin thrombi

and vasculitis.

Conference Comment:

In addition to outbreaks in domestic turkeys,

E. rhusiopathiae outbreaks

have also been reported in laying hens in Europe,

3 and sporadically

in a variety of other captive and free-ranging birds. The organism is fas-tidious

and able to survive in the environment for extended periods. It may be

transmitted by cuts and abrasions or through ingestion. It is generally

considered to follow an acute course characterized by septicemia, but a chronic

form also occurs in turkeys,

1 which appear to be most susceptible to

infection. In addition to thromboembolism, bacterial endocarditis and joint

infections

1 may be seen in affected turkeys, among other signs of

septicemia. Thrombosis and hemorrhage are commonly reported in avian species

infected with

E. rhusiopathiae, reflecting the vasculocentric nature of

the disease. Grossly, carcasses of affected birds are in good flesh and

exhibit organomegaly of the liver, spleen and kidneys, as well as eccymotic

hemorrhages in the subcutis and muscles.

1 Routes of infection

include fomites, contaminated soil, insect vectors, asymptomatic carrier animals

and contaminated feed.

3,4 Although

it has been reported, infection in psittacine birds is considered rare. In a

case report of infection in a mixed species aviary, lesions included

thrombosis, bacterial th-romboembolism, necrotizing hepatitis, necrohemorrhagic

myocarditis, and hem-orrhage.

4 E. rhusiopathiae infection

has also been reported in emus, which are large flightless birds that are

grouped with other ratites such as ostriches and rheas. Lesions similar to

those reported in other species are also seen in emus, including hepatocellular

necrosis with absence of an abrupt inflammatory response. Bacteria may be

observed in multiple organs, including the kidneys and small intestine as well

as the liver; the presence of fibrin thrombi, while prominent in many cases,

may be variable.

5

References:

1. Bobrek K, Gawel A, Mazurkiewicz M. Infections with Erysipelothrix

rhusiopathiae in poultry flocks. World's Poultry Science Journal.

2013; 69(4):803-812.

2. Bricker JM, Saif YM. Erysipelas. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of Poultry. 12th

ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008:909-922.

3. Eriksson H, Bagge E, Båverud V, Fellstrom C, et al. Erysipelothrox

rhusiopathiae contamination in the poultry house environment during

erysipelas outbreaks in organic laying hen flocks. Avian Pathol. 2014;

43(3):231-237.

4. Galindo-Cardiel I, Opriessnig T, Molina L, Juan-Salles C. Outbreak of

mortality in psittacine birds in a mixed-species aviary associated with Erysipelothrix

rhusiopathiae infection. Vet Pathol. 2012; 49(3):498-502.

5. Morgan MJ, Britt JO, Cockrill JM, Eiten ML. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

infection in an emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). J Vet Diagn Invest.

1994; 6:378-379.

6. Reboli, A, Farrar WE. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: An occupational

pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989; 2:354-359.