Signalment:

Gross Description:

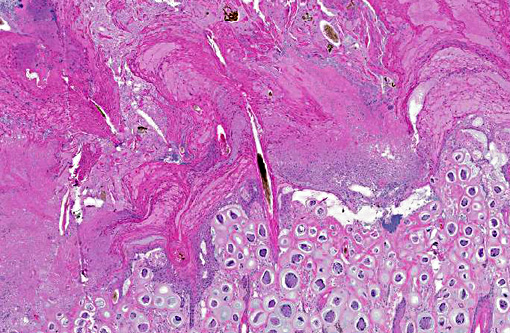

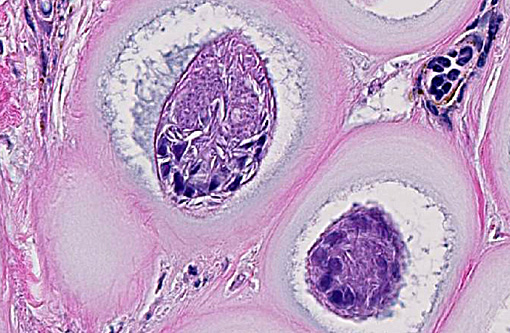

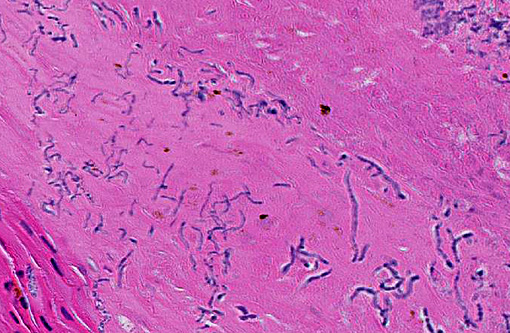

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

B. tarandi is the species of Besnoitia known to affect caribou and the closely related reindeer. The life cycle of this species is not currently known. The domestic cat is the definitive host for the 3 species with a known life cycle, but the definitive host for the B. tarandi is unknown although other Felid species such as cougars and lynx may be a possibility.(2)

An epizootic event of besnoitiosis occurred in a zoo in Manitoba starting in 1983.(4) The initial cases were diagnosed in 2 caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) that died of pneumonia. Over the course of 3 years besnoitiosis spread to mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus hemionus), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) and a second isolated group of caribou. Twenty-eight caribou, 10 mule deer and 3 reindeer were euthanized or died as a result of this epizootic. The means of transmission in this case was thought to be biting flies.

In wild woodland caribou, besnoitiosis appears to be a relatively common (23% infection rate in one study) chronic and mild disease.(6) Lesions are most often confined to the skin of the extremities causing alopecia with mild skin thickening and crusting. In some cases however, the disease appears to be much more widespread and severe with ulceration of the skin, cysts in the sclera, conjunctiva, nasal mucosa, visceral serosa, tendons, tendon sheaths, hoofs and testes.(1,4) In this case, cysts were found within the nasal mucosa, sclera, conjunctiva, lymph nodes and meninges as well as the skin.

Although B. tarandi is not of zoonotic concern and meat from affected animals should be safe to eat, the relatively common prevalence, poorly understood natural history of the disease and the potential for transmission to other wildlife species makes besnoitiosis a disease of potential emerging concern for translocation of reindeer and caribou from arctic regions to more southern ones.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Haired skin: Protozoal cysts, numerous.Â

2. Haired skin: Hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, epidermal, diffuse, severe, with segmental epidermal necrosis and numerous mixed bacterial colonies.Â

Conference Comment:

Besnoitia spp. have a two-host life cycle with disease occurring in the definitive host.(3) The disease can be divided into acute, subacute, and chronic stages. The acute stage is characterized by tachyzoite proliferation within vascular endothelial cells. Bradyzoites proliferate during the subacute and chronic stages within mesenchymal cells resulting in the cyst formation such as observed in this case.(5)

Recently immunohistochemistry and other special stains were used to characterize the tissue cyst layers of Besnoitia besnoiti in cattle. Tissue cysts were found in multiple organs including the corium of the claw where they contributed to chronic laminitis. The cysts are composed of host cell wall with enlarged nuclei containing a parasitophorous vacuole with bradyzoites. Additionally, an inner and outer cyst wall were distinguished, and in chronic stages, extracystic zoites were observed.(5)

References:

1. Ayroud M, Leighton FA, Tessaro SV: The morphology and pathology of Besnoitia sp. In reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus). J Wildl Dis 31(3):319-326, 1995

2. Dubey JP, Sreekumar C, Rosenthal BM, Vianna MCB, Nylund M, Nikander S, Oksanen A: Redescription of Besnoitia tarandi (Protzoa:Apicomplexa) from the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Int J Parasitol 34:1273-1287, 2004

3. Ginn PE, Mansell JL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:709-710.

4. Glover GJ, Swendrowski M, Cawthorn RJ: An epizootic of besnoitiosis in captive caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus), and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus hemionus) J Wildl Dis 26:186-195, 1990

5. Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Majzoub-Altweck M, Scharr JC, Schares G, Hermanns W. Naturally acquired bovine besnoitiosis: histological and immunohistochemical findings in acute, subacute, and chronic disease. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(3):476-488.

6. Lewis RJ: Besnoitia infection in Woodland caribou Can Vet J 30:436, 1989