Signalment:

Gross Description:

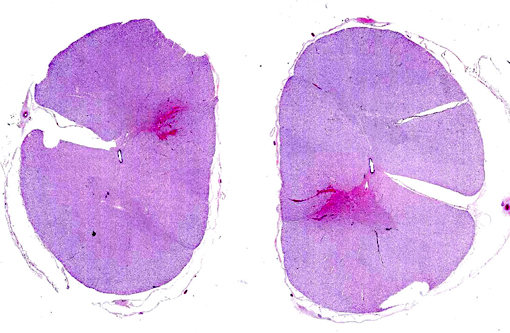

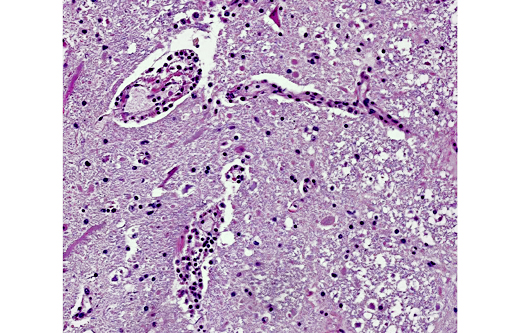

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Antemortem diagnosis of rabies remains problematic, but the disease should be considered in horses whenever there are rapidly progressing and/or diffuse neurologic signs. Differentials for rabies include hepatoencephalopathy, Eastern equine encephalitis, herpesviral encephalomyelopathy, protozoal encephalomyelitis, nigropallidal encephalomalacia, botulism, lead poisoning, cauda equine neuritis, meningitis, space-occupying masses, CNS trauma, or esophageal obstruction.(4)

Equine rabies can also be challenging to diagnose on necropsy. Numerous cases of disease confined to the spinal cord in horses have been reported making it advisable to include spinal cord in routine rabies testing in horses.(1) Horses are also unique in that their lesions often are associated with significant hemorrhage making it a consideration for focal spinal lesions associated with hemorrhage. Finally, as is demonstrated in this case, greater than half of the rabies cases in horses do not have identifiable Negri bodies.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Rabies virus is an enveloped RNA virus of the family Rhabdoviridae and the genus Lyssavirus; it causes meningoencephalomyelitis, ganglionitis and parotid adenitis, is almost invariably fatal, and is capable of affecting any mammalian species. Following infection with the virus, herbivores, unlike carnivores, are typically dead-end hosts. Reservoir hosts may vary temporally and regionally; among the most common are foxes, skunks, raccoons, feral dogs, wolves, jackals and mongoose. Fructivorous, insectivorous and vampire bats are also capable of transmitting rabies virus. Rabies viral neurotropism is due to a viral coat protein known as rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG), which binds several neural tissue receptors, including neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). Virus inoculation typically occurs through contaminated saliva entering bite wounds inflicted by rabid animals. Initial viral replication occurs in myocytes adjacent to the bite wound, with subsequent invasion of the local neuromuscular junction and, eventually, the CNS and paravertebral ganglia via axoplasmic flow. Following viral replication in the CNS, there is centrifugal spread to salivary glands, nasal mucosa and adrenal glands.(3,4)

Three clinical manifestations of rabies are described: dumb, furious, and paralytic forms. The two most common clinical signs in affected mammals are progressive paralysis and aberrant behavioral patterns. In addition, horses in particular can have clinical signs associated with spinal cord injury, such as pelvic limb lameness, proprioceptive defects, ataxia, paralysis, and colic. Other reported species-specific features of the clinical progression of rabies include the following: cattle commonly exhibit excessive salivation and vocalization, swine are often found dead with no preceding clinical signs, sheep display passive behavior and dogs appear agitated or anxious. There are typically no gross lesions, although in horses infection may be associated with spinal cord hemorrhage. Historically, intracytoplasmic viral inclusions (i.e., Negri bodies) occur in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum in herbivores and in neurons of the hippocampus in carnivores. In most mammalian species, Negri bodies are identified in 70% to 85% of affected animals; however, in horses this figure falls to 30% to 50%.(3,4) As an example of equine rabies with lesions limited to the spinal cord, without demonstrable Negri bodies, this case illustrates the potential variability of gross and histopathologic findings associated with rabies virus infection.

References:

2. Green S, Smith L, Vernau W, et al. Rabies in horses: 21 cases (1970-1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;200:1133-1137.

3. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:413-416.

4. Reed S, Bayly W, Sellon D, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders; 2004:644-646.