Signalment:

Gross Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Adrenal gland:

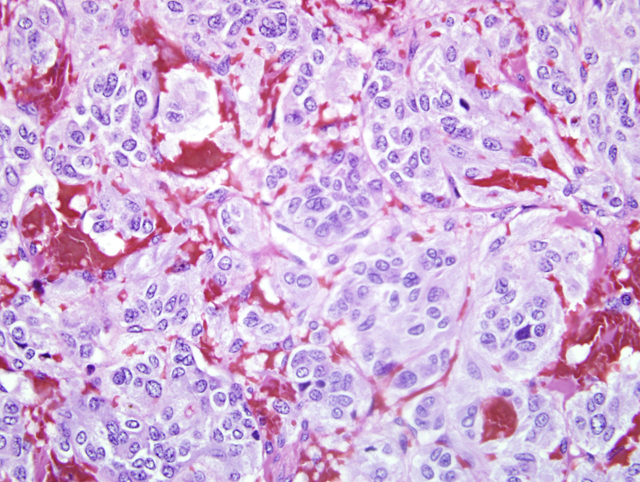

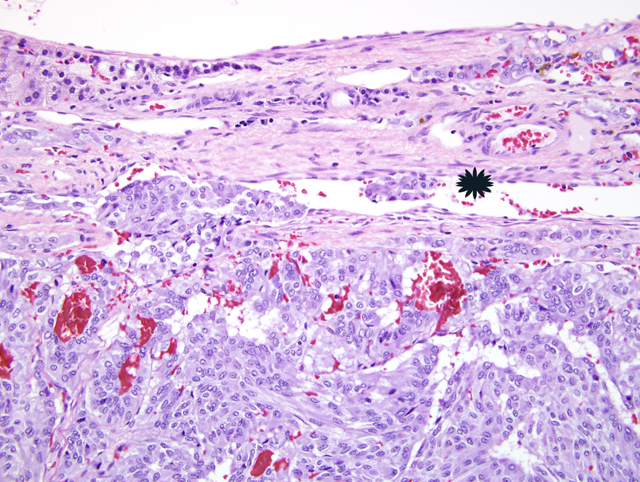

1) Pheochromocytoma

2) Myelolipoma (not in all sections)

Lab Results:

Tumor cells were negative for GFAP, VIP, somatostatin, S-100, cytokeratin, NFP and substance P.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

A diagnosis of a malignant pheochromocytoma in domestic animals is based on invasion of the capsule and adjacent structures (e.g. vena cava) and/or metastasis. In humans, both capsular and vascular invasion may be encountered in benign lesions. Therefore, a diagnosis of malignancy is based exclusively on the presence of metastases.7 The metastases may involve regional lymph nodes, as well as more distant sites including liver, lung, spleen and bone.3,7 There are only a few reports of malignant pheochromocytomas with multiple metastases in domestic animals.10

Functional pheochromocytomas have been reported infrequently in animals.2 These tumors may occasionally be associated with clinical signs as a result of the continuous or episodic secretion of one or more of the catecholamines: epinephrine, norepinephrine or dopamine.2,7 Elevations of blood pressure induced by the sudden release of catecholamines can precipitate acute congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, myocardial infarction, ventricular fibrillation and cerebral hemorrhage.2,7 In this case, clinical cardiac abnormalities and histologic findings of myocardial fibrosis (slide not submitted) might suggest catecholamine production by the tumor. Human pheochromocytomas are known to produce sustained hypertension in one-third of cases and experimental catecholamine administration induces myofibrillar degeneration and interstitial fibrosis in animals.1 However, plasma catecholamine levels and urinary excretion of catecholamines and their metabolites were not measured in this case.Â

In nonhuman primates adrenal gland tumors are rare. Recognized tumors include: myelolipomas, pheochromocytomas, cortical adenomas, cortical adenocarcinomas, paragangliomas, medullary fibromas and hemagioma/angiomas.1 In New World nonhuman primates with spontaneous endocrine neoplasia the adrenal gland is most frequently affected with pheochromocytomas reported most often.5 Other adrenal gland tumors in New World monkeys include myelolipomas.1 Among prosimian and Old World primates pheochromocytomas have been reported in the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolygus monkey (Macaca fascicularis).5 In humans, pheochromocytoma is an uncommon neoplasm and is usually a benign tumor affecting one or both adrenals.5

At the New England Primate Research Center, myelolipomas and pheochromocytomas are the two most commonly recognized neoplasms in the adrenal glands of aged Cotton-top tamarins. In humans, most pheochromocytomas occur sporadically in adults with a slight female preponderance.7 About 10% occur in several, mostly autosomal dominant, familial syndromes including the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes, type I neurofibromatosis, von Hippel-Lindau disease and Sturge-Weber syndrome.7 In the familial syndromes, many arise in childhood with a strong male preponderance. Most of the tumors in the syndromes are bilateral (70%), but in the nonfamilial setting only 10-15% are bilateral.7

In some of the sections of adrenal from this animal a myelolipoma was also recognized. Myelolipomas are a benign lesion commonly encountered in the adrenal glands of cattle and nonhuman primates and infrequently in other animals.2 They are composed of accumulations of well-differentiated adipose cells and hematopoietic tissue, including both myeloid and lymphoid elements. Focal areas of mineralization or bone formation may occur. Although the origin of these lesions is uncertain, they appear to develop by metaplastic transformation of cells in the adrenal cortex or cells lining adrenal sinusoids.2

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Tumor development within the adrenal medulla has been associated with multiple factors, including genetics, dietary factors, chronic high levels of growth hormone or prolactin associated with pituitary tumors, and autonomic nervous system stimulation.3

In dogs, caval thrombi occur more frequently with pheochromocytomas than adrenal cortical tumors. The caval thrombus primarily develops as an intraluminal extension from the phrenicoabdominal veins rather than by direct invasion of the vena cava.6

Rats have three types of chromaffin cells: epinephrine cells, norepinephrine cells, and small granule-containing cells, unlike human chromaffin cells, which contain both epinephrine and norepinephrine granules within a single cell.8 Either epinephrine or norepinephrine secreting cells, or both may be found within a pheochromocytoma. Ultrastructurally, norepinephrine granules have an eccentrically placed, small, electron dense core that is surrounded by a wide submembranous space.2 Epinephrine granules have a coarse granular core that is less dense than that of norepinephrine granules, and has a narrower submembranous space.2 In dogs, norepinephrine appears to be the principle catecholamine secreted by pheochromocytomas.2

References:

2. Capen CC: Tumors of the endocrine gland. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp. 629-638. Iowa State Press, Ames, Iowa, 2002

3. Capen CC: Endocrine glands. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 419-422. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

4. De Cock HE, MacLachlan NJ: Simultaneous occurrence of multiple neoplasms and hyperplasias in the adrenal and thyroid gland of the horse resembling multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome: Case report and retrospective identification of additional cases. Vet Pathol 36:633-636, 1999

5. Dias JLC, Montali RJ, Strandberg JD, Johnson LK, Wolff MJ: Endocrine neoplasia in new world primates. J Med Primatol, 25:34-41, 1996

6. Kyles AE, Feldman EC, De Cock HE, Kass PH, Mathews KG, Hardie EM, Nelson RW, Ilkiw JE, Gregory CR: Surgical management of adrenal gland tumors with and without associated tumor thrombi in dogs: 40 cases (1994-2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 223:654-662, 2003

7. Maitra A, Abbas AK: The endocrine system. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Kumar V, Abbas, AK, Fausto N, 7th ed., pp. 1219-1223. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2005

8. Pace V, Perentes E, Germann P: Pheochromocytomas and ganglioneuromas in the aging rats: Morphological and immunohisochemical characterization. Toxicol Pathol, 30:492-500, 2002

9. Raue F, Frank-Raue K: Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: 2007 update. Horm Res, 68:101-104, 2007

10. Sako T, Kitamura N, Kagawa Y, Hirayama K, Morita M, Kurosawa T, Yoshino T, Taniyama H: Immunohistochemical evaluation of a malignant pheochromocytoma in a wolfdog. Vet Pathol, 38:447-450, 2001

11. Vogel P, Fritz D: Cardiomyopathy associated with angiomatous pheochromocytoma in a Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol 40-468-473, 2003