Signalment:

Gross Description:

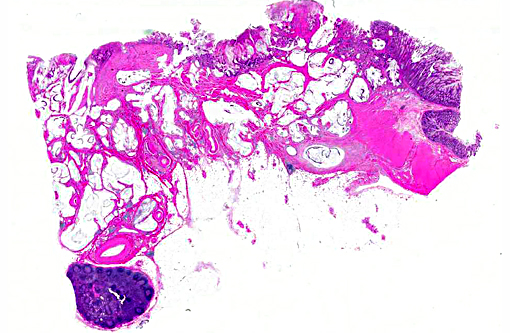

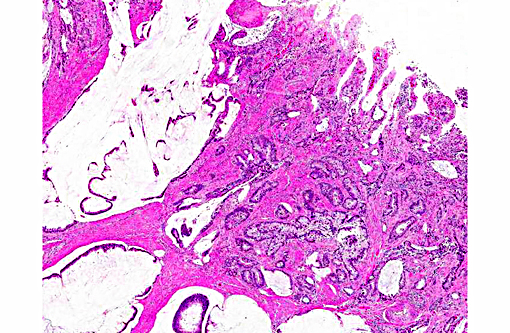

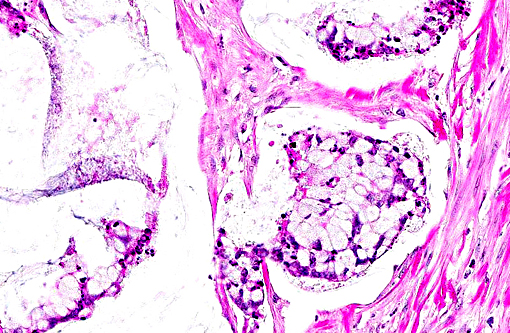

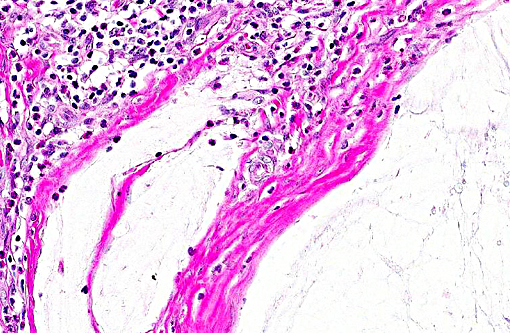

Histopathologic Description:

Microscopic diagnoses of tissues not submitted:

Jejunum: Leiomyoma.

Heart: 1. Endocardiosis, right and left atrioventricular valves.

2. Myocardial necrosis, degeneration, mineralization, fibrosis.

3. Atrial subendocardial fibroelastosis, bilateral with jet lesion.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Colon: 1. Adenocarcinoma, mucinous.

2. Colitis, proliferative, lymphoplasmacytic, eosinophilic, multifocal, marked with goblet cell hyperplasia and crypt abscesses.

Lab Results:

| Value | Ref. Interval | |

| WBC | 6.5 x 103/μL | 3.8 12.6 x 103/μL |

| RBC | 5.34 x106/μL | 4.5-6.4 x 106/μL |

| MCV | 60 fL | 67-77 fL |

| MCH | 18.4 pg | 22.1- 25.84 pg |

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The intestinal adenocarcinomas are classified according to histological features and include:

1. Papillary adenocarcinoma

2. Tubular adenocarcinoma

3. Mucinous adenocarcinoma

4. Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma

Intestinal adenocarcinoma is the most frequently diagnosed tumor of older macaques.(4,5,11,12,15) A high prevalence of intestinal tumors at the ileocecal junction in aged animals (over 20 years) has been documented.(11,12,13,14)

Intestinal neoplasms are rare in large animal species. Intestinal adenocarcinomas in dogs are seen in the proximal small intestine and large intestine. Regional metastasis to mesenteric lymph nodes may occur. Distant metastasis to the liver, spleen and lungs occurs less frequently. Boxers, collies, poodles and German shepherds are predisposed.(2)

In cats, intestinal adenocarcinoma is less common than lymphosarcoma. In sheep, the occurrence of intestinal adenocarcinomas is associated with ingestion of bracken fern and certain weeds. In cattle, intestinal adenocarcinoma is associated with bracken fern ingestion and bovine papillomavirus-4 infection and frequently metastasize to liver, lung, kidney, uterus and ovaries.(2) In contrast to other simian species, colonic carcinomas are frequently seen in cotton-top tamarins(1,8) and has been linked to the high prevalence of chronic colitis in these animals.(9)

Although, the tumorigenesis has not been completely studied in non-human primates, long term feeding of a high-fat, low-fiber diet has been shown to cause pre-malignant alterations in African green monkeys.(11) A novel Helicobacter sp. has been isolated from inflamed colons of cotton-top tamarins, which are predisposed to developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colon cancer.(13) Also, the colonic adenocarcinoma in rhesus monkeys has been linked to Helicobacter macaque.(9) Mutation in K-ras has been observed in approximately 40 % of colonic adenocarcinoma of humans; however, no such mutations were recorded in macaques with intestinal adenocarcinoma.(11)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Participants also discussed the classic gross description of intestinal adenocarcinoma as having a napkin ring-like appearance due to constriction caused by the desmoplastic response elicited by the neoplasm, which is present in the excellent gross image provided by the contributor. The desmoplastic response is related to the interaction of tumor cells with the surrounding stroma via many types of mediators including cytokines and growth factors. One such mediator is platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), which stimulates fibroblasts and results in excessive production of collagen,(7) often referred to as a scirrhous response. Tumor cells can have various effects on stromal fibroblasts including causing them to differentiate into other types of mesenchymal cells, such as myofibroblasts, and inducing the production of cytokines that stimulate tumor growth, as well as stimulating them to de-differentiate and produce abnormal extracellular matrix. Growth factors are also sequestered within the stroma, and the actions of tumor cells can control their release.(7) Intestinal adenocarc-inoma is described in humans(12) and domestic animal species(2) as having a similar gross appearance, and the mucinous variant is indicative of a poorer prognosis due the mucinous excretions facilitating invasion through the intestine wall.(12)

As mentioned by the contributor, intestinal adenocarcinoma in sheep is thought to be at least partially related to the ingestion of bracken fern, or may be related to the application of fertilizers or herbicides.(2,6) Bracken fern affects grazing animals throughout the world and causes a variety of syndromes ranging from neurologic and cardiac conditions in horses and pigs to enzootic hematuria in cattle and sheep. Bracken fern-induced neoplasia is most commonly associated with the urinary bladder and upper alimentary tract and is most often described in cattle, where it may also be associated with bovine papil-lomavirus-2. All parts of the plant are considered toxic and contain multiple toxins, including a thiaminase as well as multiple carcinogens, ptaquiloside being the most common.(10) There is also a recent report of intestinal adenocarcinoma in farmed sika deer where bracken fern may have played a role, in combination with other factors.(6) Intestinal carcinomas in sheep are more commonly located in the small intestine, and less commonly in the colon, and they are also associated with luminal constriction and a marked desmoplastic response. Intestinal adenocarcinomas in large domestic species other than sheep, and other than those associated with bracken fern or papill-omavirus, are uncommon.(2)

References:

1. Barack M. Intestinal carcinomas in two tamarins (Saguinus fuscicollis, Saguinus oedipus) of the German Primate Center. Lab. Anim. 1988; 22(2): 14-147.

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier; 2007:1-106.

3. DePaoli A, McClure HM. Gastrointestinal neoplasms in nonhuman primates: a review and report of eleven new cases. Vet Pathol Suppl. 1982;7:104-25.

4. Harbison CE, Taheri F, Knight H, Miller AD. Immunohistochemical characterization of large intestinal adenocarcinoma in the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol. 2015;52(4): 732-740.

5. Johnson EH, Morgenstern SE, Perham JM, Barthold SW. Colonic adenocarcinoma in a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). J Med Primatol. 1996;25:435-8.

6. Kelly PA, Toolan D, Jahns H. Intestinal adenocarcinoma in a herd of farmed sika deer (Cervus nippon): a novel syndrome. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(1): 193-200.

7. Kusewitt DF. Neoplasia and Tumor Biology. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:303-304.

8. Liu CH, Chen YT, Wang PJ, Chin SC. Intestinal adenocarcinoma with pancreas and lymph node metastases in a captive cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus). J Vet Med Sci. 2004; 66:1279-1282.

9. Marini RP, Muthupalani S, Shen Z, Ellen M, Buckley EM, Alvarado C, et al. Persistent infection of rhesus monkeys with Helicobacter macacae and its isolation from an animal with intestinal adenocarcinoma. J Med Microbiol. 2010 Aug;59(Pt 8): 961-9.

10. Newman SJ. The Urinary System. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease E edition. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:652.

11. OSullivan MG, Carlson CS. Colonic adenocarcinoma in rhesus macaques. J Comp Path. 2001; 124:212-215.

12. Rodriguez NA, Garcia KD, Fortman JD, Hewett TA, Bunte RM, Bennett BT. Clinical and histopathological evaluation of 13 cases of adenocarcinoma in aged rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). J Med Primatol. 2002; 31:7483.

13. Saunders KE, Shen Z, Dewhirst FE, Bruce J, Paster BJ, Dangler CA, et al. Novel intestinal Helicobacter species isolated from cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus) with chronic colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37(1): 146-151.

14. Uno H, Alsum P, Zimbric ML, Houser WD, Thomson JA, Kemnitz JW. Colon cancer in aged captive rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Am J Primatol. 1998; 44:19-27.

15. Valverde CR, Tarara RP, Griffey SM, Roberts JA. Spontaneous intestinal adenocarcinoma in geriatric macaques (Macaca sp.). Comp Med. 2000; 50:540-4.