Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 8, Case 1

Signalment:

8-month-old, intact female, Pembroke Welsh Corgi, Canis lupus familiaris, canine.

History:

This patient presented with non-pruritic, erythematous, ulcerated, crusty skin lesions affecting the nose, muzzle, periocular tissue OU, ear pinna AU, and multiple nail beds of all four feet. Lesions started a month ago.

Gross Pathology:

Three punch biopsies of haired skin from multiple anatomic locations (forehead, muzzle, digit 4 of right hindfoot) were submitted for evaluation, with no overt gross findings.

Laboratory Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture – trace numbers of Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus equorum, Rummeliibacillus sp., and Cellululosimicrobium cellulans

Fungal culture – absence of growth

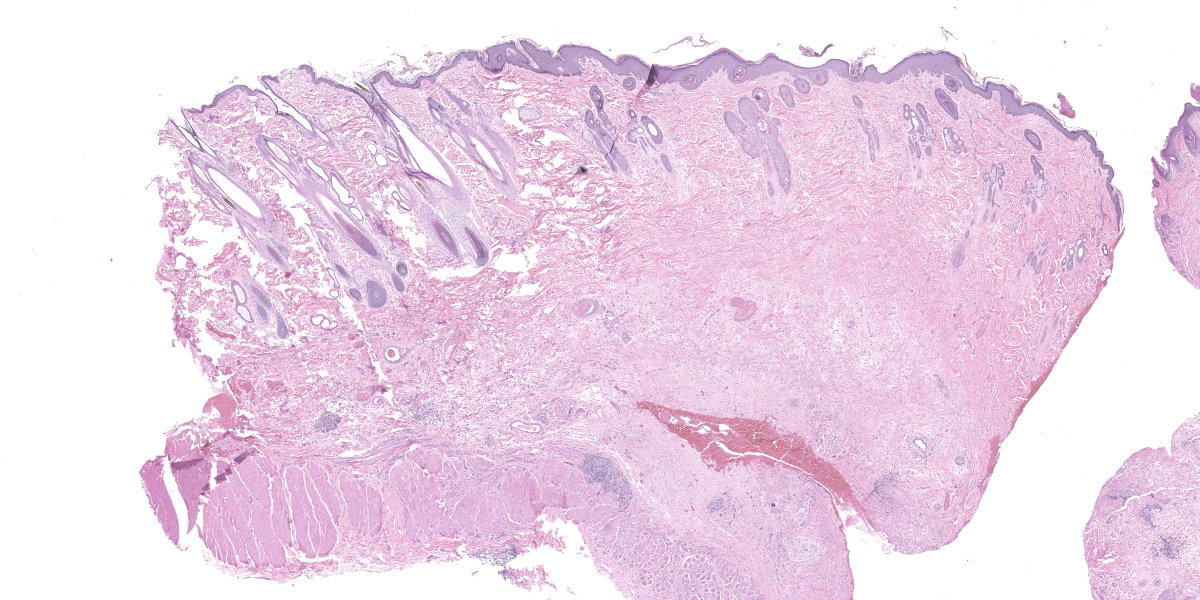

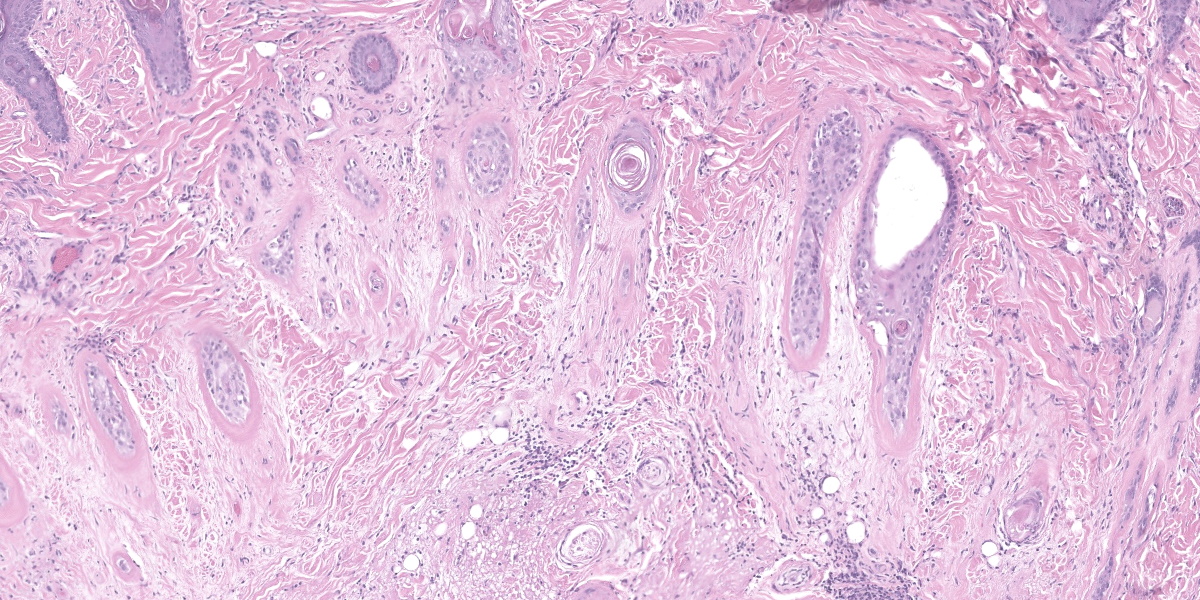

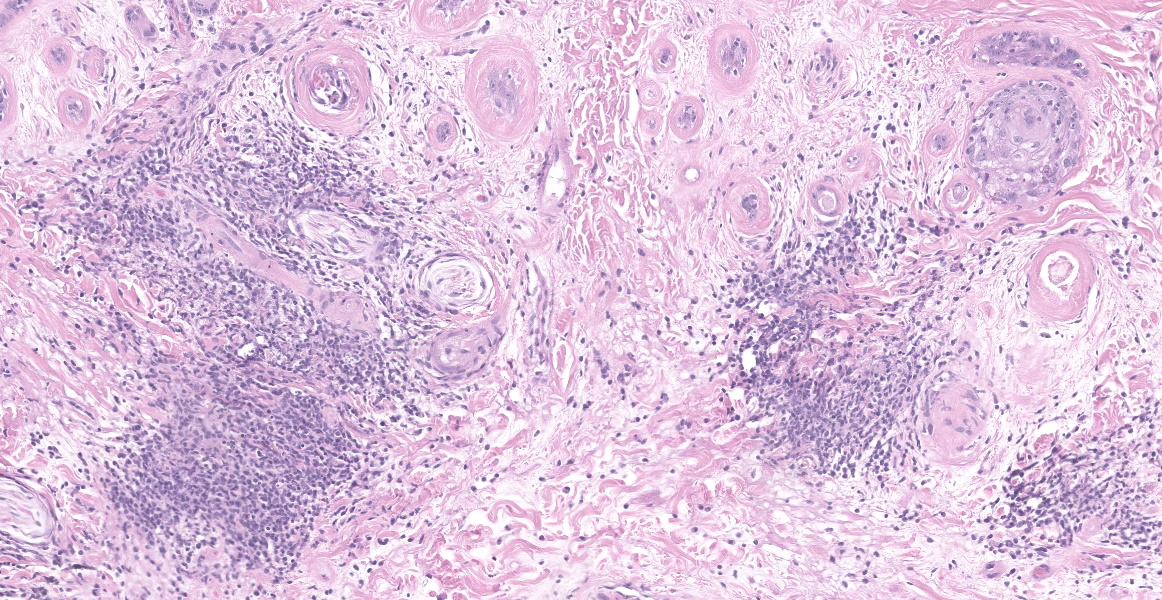

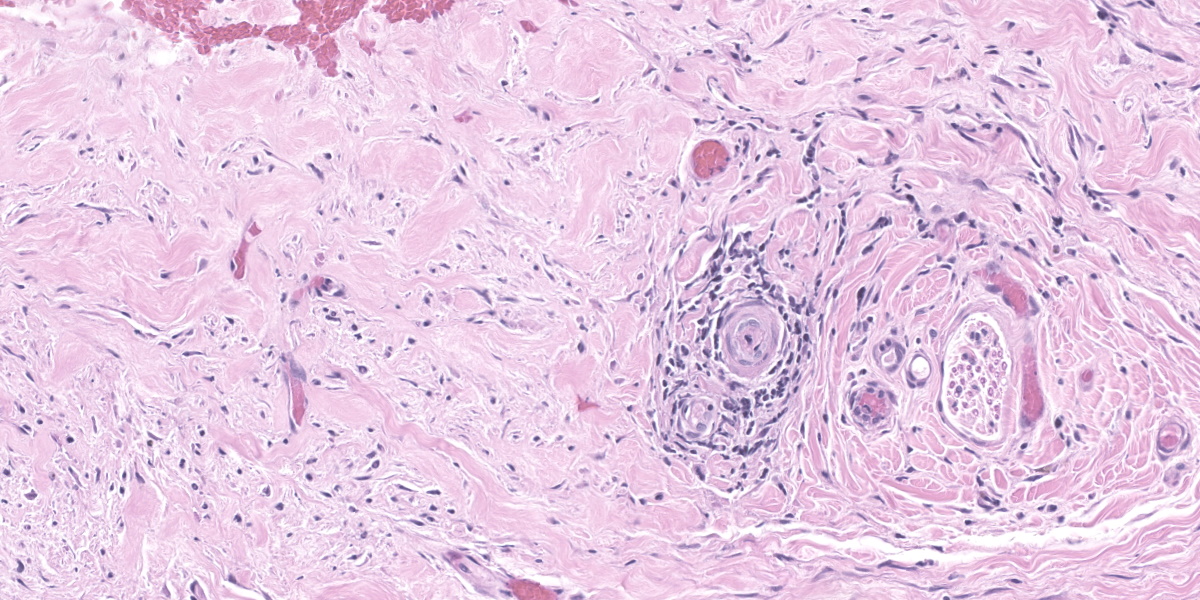

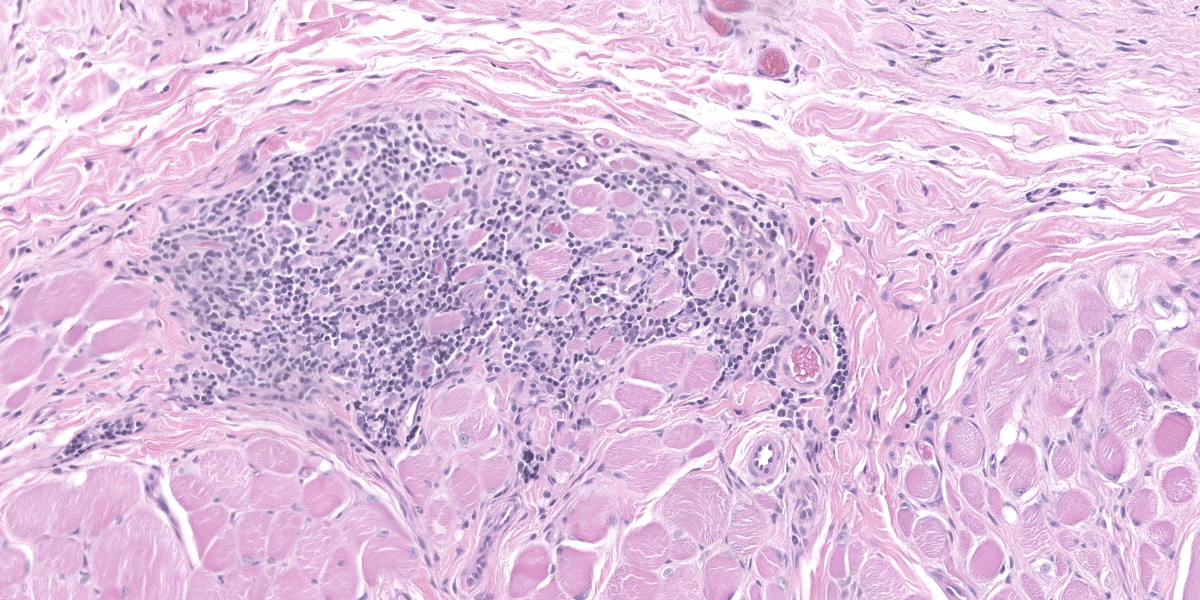

Microscopic Description:

Haired skin (forehead, muzzle, digit 4 of right hindfoot): Multiple sections of haired skin are examined in which similar features are observed in all samples. Extending from the mid to deep dermis, and sharply demarcated from adjacent normal tissue in some sections, collagen fibers are regionally disorganized and pale to hypereosinophilic with variable loss of distinct bundle architecture. Medium to small caliber dermal vessels are distorted, characterized by pale, hyalinized eosinophilic tunics with loss of distinct separation of layers. Affecting other vessels, are circumferential perivascular cuffs of lymphocytes and plasma cells with fewer neutrophils and macrophages, which extend into the adjacent dermal stroma. Remaining pericytes and/or smooth muscle nuclei are frequently enlarged and prominent. Occasional aggregates of lymphocytes and histocytes are embedded in the dermis. Occasional clusters of lymphocytes and macrophages are also observed in the skeletal muscle layer, with separation, attenuation, and atrophy of affected fibers. Dermal nerve fibers have shrunken axons in decreased quantity, and rare lymphocytes and macrophages are embedded within affected fibers. Superficial to the affected dermis, multiple hair follicles are atrophied with a prominent fibrous root sheath. The overlying epidermis is hyperplastic, covered by segments of compact orthokeratotic to parakeratotic keratin that sometimes distend follicular ostia. Occasional serocellular crusts are also present.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Haired skin (forehead, muzzle, digit 4 of right hindfoot): Vasculitis with ischemic dermatopathy, regionally extensive, severe

Contributor’s Comment:

Based on the clinical history, signalment, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of ischemic dermatopathy was warranted in this case. Ischemic dermatopathies (ID) refer to a group of cutaneous diseases that involve inflammation of the skin, vessels, and sometimes muscle or subcutaneous tissue, derived from a variety of causes. These conditions have been reported in humans7 and dogs.1,4,6,7,9,10 There are 5 main subtypes reported in dogs which include: 1) familial dermatomyositis (DM), 2) juvenile onset ischemic dermatopathy (dermatomyositis-like disease), 3) localized post-rabies vaccine panniculitis, 4) generalized vaccine-induced ischemic dermatopathy, and 5) generalized idiopathic ischemic dermatopathy.4,6,10 Although the pathogenesis is incompletely elucidated for these diseases, the generally accepted premise is that of a cell-poor vasculitis, leading to decreased oxygen perfusion of the tissue, and subsequent ischemic change.1,4,9

Across the various subgroups of ischemic dermatopathies, clinical, gross, and histopathologic features are often similar. Clinically overall, anatomic locations most susceptible for mechanical trauma (i.e., bony protuberances), or distal extremities (i.e., phalanges) are preferentially affected.4 Gross lesions include alopecia, scab formation, variation in pigmentation (hyper- or hypo-), and thinning of the skin.4,8 Histopathologic lesions consist of follicular atrophy, hyperkeratosis, smudgy and indistinct collagen fibers, interface dermatitis and/or clefting at the epidermal basement membrane.6,8 Diagnosing a specific subtype can sometimes be challenging, which requires a thorough clinical history and signalment, coupled with gross and histopathologic features. The use of electromyography or muscle physiology studies have also been useful in some cases.1,3

Familial Dermatomyositis (FDM) and juvenile onset ischemic dermatopathy (dermatomyositis-like or DM-like) have several identical clinicopathological features. They both occur in young dogs. Most commonly, lesions originate on the muzzle, periorbital and perioral tissues, dorsum of the distal phalanges and sometimes footpads,4,8 but additionally the tips and folds of the pinnae, tip of the tail, and claw folds can also be affected.4 Muscle changes and clinical abnormalities can be subtle but are often detected with histopathologic evaluation and/or electromyographic studies.3 When present, atrophy can be most apparent affecting the temporal and masseter muscles.4 Megaesophagus, growth retardation, and infertility are also reported findings.4 FDM was first described in Collies,5 with later reports in Shetland sheepdogs, Portuguese water dogs, and Belgian Tervuren dogs3,4,6,10 whereas DM-like disease occurs sporadically in breeds without a scientifically proved genetic or familial component.2,10

Localized post-rabies panniculitis typically occurs 1 to 3 months after vaccine administration,6 and initially, there is focal alopecia at the affected site that can progress to hyperpigmentation.6 The neck and shoulder region in the vicinity of the scapulae, are primarily affected.4. Deposition of rabies viral antigens into the wall of vessels is suspected as the inciting stimulus.4 Breeds predisposed to this condition include Toy and Miniature Poodles and Bichon Frises,4,6 but there are reports also involving Yorkshire terriers and Chihuahuas.8 The most characteristic histopathologic findings are lymphocytic perivascular inflammation and vasculitis,11 coupled with other previously described features of ID. This condition can become more widespread and severe in some adult dogs, with the development of fever, lethargy, depression, and/or elevation in liver enzymes (generalized vaccine-induced ischemic dermatopathy).4,6

Generalized vaccine or idiopathic ischemic dermatopathy are identical clinicopathologically, and the presence of alopecia over a previous rabies vaccination site can assist in differentiating the two subtypes.9 Generalized idiopathic ischemic dermatopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion.

For this case, the top three subtype differentials included: dermatomyositis-like disease, generalized idiopathic ischemic dermatopathy, and generalized vaccine-induced dermatopathy.

Contributing Institution:

250 McElroy Hall

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology

College of Veterinary Medicine

Oklahoma State University

Stillwater, OK 74078 USA

https://vetmed.okstate.edu/veterinary-pathobiology/index.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin, dermis: Vasculitis, lymphohistiocytic, multifocal, moderate with regionally extensive adnexal atrophy, rare thrombi, and cell poor interface dermatitis.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Charles Bradley, Associate Professor of Anatomic Pathology at the University of Pennsylvania. A perennial visitor to the WSC, Dr. Bradley emphasized cutaneous patterns of skin disease with participants. The first case is a good example of an interface dermatitis, albeit a cell-poor one. Case features are best observed first from low magnification with disruption of dermal collagen, loss of adnexal structures, and vasocentric lesions being helpful pickups that point at the underlying pathogenesis. Key histologic features on high magnification include disruption of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane, rare thrombi, and mild vasculitis. Although not strictly necessary for this case, PAS highlighted the basement membrane nicely and Movat’s pentachrome highlighted select vessels.

Dr. Bradley also covered ancillary changes in section with conference participants. These included vacuolation of basal keratinocytes (likely a mild processing artifact) and focal parakeratosis which was attributable to tissue response to injury. In the superficial dermis, there was also granulation tissue present suggestive of previous ulceration and re-epithelization of the epidermis, perhaps from a previous episode of diminished blood flow. Likewise, the mild myositis in this case is likely a bystander lesion rather than a primary dermatomyositis – in Dr. Bradley’s experience, muscle changes are rare to absent in histologic section in dermatomyositis (DM). Finally, it is also important to rule out other processes in the skin with ischemic changes such as reactive histiocytosis.

The clinical history of a young animal is helpful in this case and is suggestive of a vaccine-associated event. Histologically however, this is not distinguishable from DM. In addition, the location of the hyperpigmented alopecic skin (‘poodle patch’) may or may not be close to the site of vaccination, reflecting the systemic nature of this vasculitis. Deeper punch biopsies that sample the vaccine site may identify lymphohistiocytic aggregates within the subcutis that may contain vaccine adjuvant though. Dr. Bradley also touched on the role of anti-IL-31 therapy in dermatology cases, to include the use of oclacitinib and lokivetmab in modulating immune-related conditions. Apoquel, Cytopoint, and similar emerging therapies have been tried for a variety of canine skin conditions with reasonable success as an adjunct to more conventional drugs such as glucocorticoids.8

References:

1. Backel KA, Bradley CW, Cain CL, Morris DO et al. Canine ischaemic dermatopathy: a retrospective study of 177 cases (2005 – 2016). Veterinary Dermatology. 2019; 30: 403-e122.

2. Bresciani F, Zagnoli L, Fracassi F, Bianchi E, et al. Dermatomyositis-like disease in a Rottweiler. Veterinary Dermatology. 2014; 25; 229-e62.

3. Ferguson EA, Cerundolo R, Lloyd DH, et al. Dermatomyositis in five Shetland sheepdogs in the United Kingdom. Veterinary Record. 2000; 146, 214 – 217.

4. Gross TL, Ihrke, PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis, 2nd ed., Blackwell Publishing. 2005; 49 – 52, 538 – 541.

5. Hargis AM, Hegreberg GA, Prieur DJ, Moore MP. Familial Canine Dermatomyositis. American Journal of Pathology. 1984; 116: 234 – 244

6. Ihrke PJ. Ischemic Skin Disease in the Dog. 31st World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings. 2006.

7. Kovacs SO, Kovacs SC. Dermatomyositis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998; 39(6), 899 – 920.

8. Levy BJ, Linder KE, Olivry T. The role of oclacitinib in the management of ischaemic dermatopathy in four dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2019; 30: 201-e63.

9. Morris DO. Ischemic Dermatopathies. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 2013; 43, 99 – 111.

10. Romero C, Garcia G, Sheinberg G, et al. Three cases of Canine Dermatomyositis-like disease. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae. 2018; 46 (Suppl 1): 276.

11. Vitale CB, Gross, TL, Magro CM. Vaccine-induced ischemic dermatopathy in the dog. Veterinary Dermatology. 1999; 10, 131-142.