Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

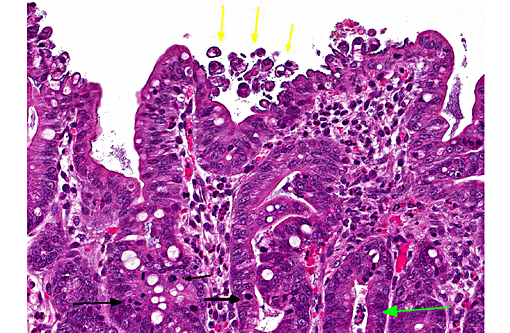

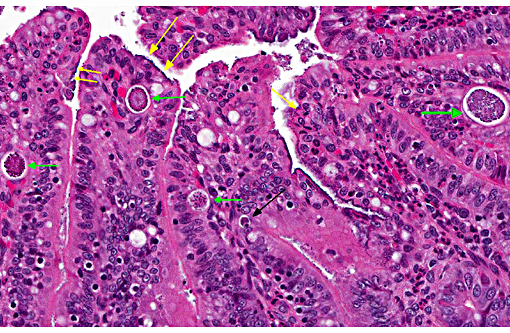

Additional sections of small and large intestine may be present on the slide. These tissues are similarly affected. The ileum is additionally characterized by numerous intraepithelial protozoal forms consistent with coccidiosis.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cecum: Typhlitis, heterophilic and lymphocytic, moderate, diffuse with moderate, multifocal adherent coccobacilli, consistent with E. coli infection.

Ileum: Enteritis, heterophilic, marked, diffuse with moderate adherent coccobacilli and coccidiosis.

Colon: Colitis, heterophilic and lymphocytic, mild, diffuse with mild multifocal adherent coccobacilli.

Lab Results:

Heavy growth of Escherichia coli from cecum

Parasitology: Positive for Eimeria media and Eimeria perforans by fecal analysis.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In this case, the ileal, cecal and colonic epithelia have numerous adherent coccobacilli. Gram staining revealed the bacteria to be gram-negative, and cultures of the intestines had heavy growth of E. coli. Concurrent coccidiosis may additionally contribute to E. coli proliferation in the intestines.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Colon and cecum: Typhlocolitis, superficial and necrotizing, multifocal, mild with edema, crypt hyperplasia and moderate numbers of adherent mucosal bacilli.

2. Ileum: Enteritis, superficial and necrotizing, multifocal, mild, with edema, crypt hyperplasia, moderate numbers of adherent mucosal bacilli and moderate numbers of apicomplexan schizonts and gamonts.

Conference Comment:

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), also referred to as attaching and effacing E. coli (AAEC), is often reported in rabbits but also affect other species such as calves, dogs and pigs. Bacteria attach to the microvillus border of intestinal epithelium by cups, which results in the formation of pedestals that can be seen ultrastructurally. Disruption of the microvillar border results in alterations in ion/fluid transport and a malabsorbtive and maldigestive diarrhea; enterocyte death, fluid secretion and an inflammatory response also play a role in the pathogenesis.(1) Bacterial attachment is mediated by the protein intimin; EPEC also express fimbriae and EPEC adherence factor. EPEC produces bacterial proteins EspA, EspB, EspD, which enter cells and disrupt signal transduction pathways and microvilli. Some strains of EPEC produce a verotoxin which plays a role in the death of enterocytes and cells of the lamina propria.(8) Infection of juvenile animals with EPEC / AAEC is often accompanied by co-infection with other intestinal pathogens such as rota or coronavirus, particularly in calves.(1)

Laboratory rabbit intestinal flora may include a wide variety of E. coli strains, including EPEC, which can be present in the absence of clinical signs; non-clinical animals may serve as reservoirs for infection. It has been suggested that inflamed intestine provides a favorable environment for pathogenic E. coli strains, which remain subclinical until other factors such as co-infections, stress or diet changes trigger an outbreak of clinical disease. Subclinical infection with various E. coli strains is important not only because of the reservoir potential, but also because many strains of E. coli, including EPEC, can be zoonotic.(7)

This case generated considerable discussion on different potential histologic diagnoses. Like the contributor, some conference participants preferred a mild to moderate typhlocolitis and enteritis; whereas others favored a more pathogenesis-oriented approach focused primarily on the EPEC-induced changes in the superficial mucosal epithelium (i.e. superficial mucosal epithelial necrosis) leading to the secondary lesions in lamina propria (i.e. inflammation, edema, and crypt hyperplasia). In sections of the small intestine intraepithelial protozoal schizonts and gamonts were described as well as rare oocysts in the intestine lumen. Conference participants also noted the absence of adipose tissue in the small sections of mesentery that are present. Such mesenteric changes are suggestive of fat atrophy and could be related to this animals nutritional status. However, the absence of adipose tissue could also be an incidental, age-related finding in a young rabbit.

References:

1. Gelberg HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery and peritoneal cavity. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:809, 374-376.

2. Levine MM. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1987; 155(3):377-389.

3. Moon HW, Whipp SC, Argenzio RA, Levine MM, Giannella RA. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infection and Immunity. 1983; 41(3): 1340-1351.

4. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell publishing; 2007:273-274.

5. Prescott JF. Escherichia coli and diarrhea in the rabbit. Vet Pathol. 1978; 15: 237-248.

6. Smith HW. Observations on the flora of the alimentary tract of animals and factors affecting its composition. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1965; 89:95-122.

7. Swennes AG, Buckley EM, Madden CM, Byrd CP, et al. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli prevalence in laboratory rabbits. Vet Microbiol. 2013; 163(3-4):395-398.

8. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:809, 165-167.