Signalment:

Gross Description:

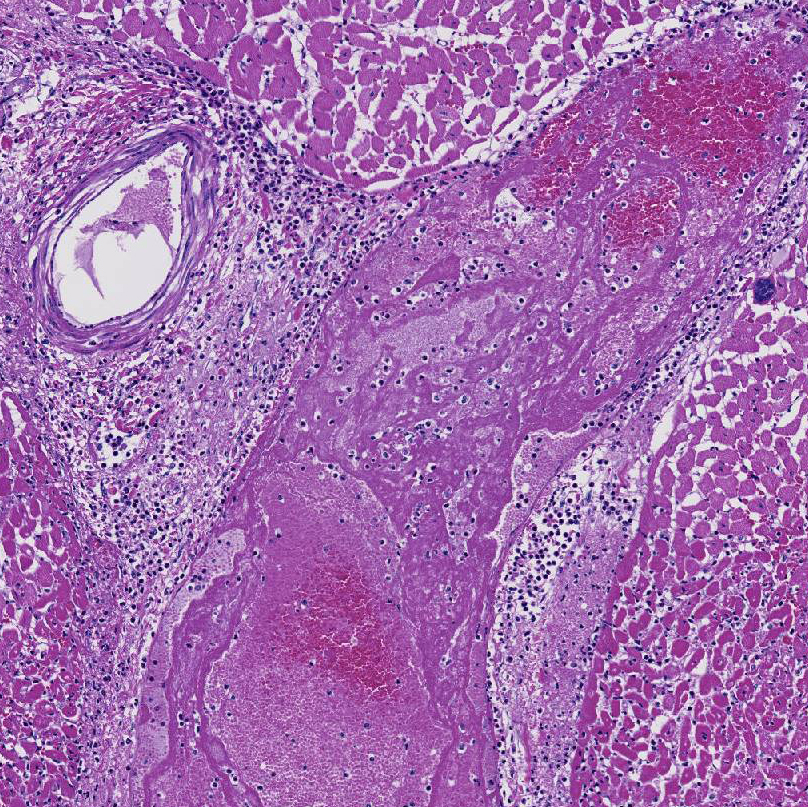

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Severe, diffuse, acute, fibrinosuppurative epicarditis; multifocal to coalescing nec-rohemorrhagic myocarditis with centrally extensive coagulative necrosis, emphysema and abundant, intralesional, gram-positive, spore-forming bacilli (Clostridium chauvoei).

2. Multifocal Sarcocystis cruzi schizonts/sarcocyts presumed.

Lab Results:

Toxic WBCs present on CBC.

Chemistry abnormalities:

[Ca] 6.5 (7.4-11.5 mg/dl); total protein 5.8 (6.5-9.3 g/dl); albumin 2.6 (3-4 g/dl); aspartase aminotransferase 1420 (53-173 U/L); creatinine kinase >16,000 (55-392 U/L); anion gap 21.9 (10-18 mmol/L); fibrinogen 1000 (300-700 mg/dl); leucopenia [WBC] 3800 (4000-12,000).

Cytology:

Smear from a left thigh aspirate: Low cellularity with few, intact, nucleated cells and numerous erythrocytes in a light pink hazy background with many, thick, box-like, bacterial rods often seen in end-to-end pairs. The nucleated cell population is composed of non-degenerate neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes in numbers and proportions consistent with peripheral blood. No overtly neoplastic cells are observed.

Skeletal muscle FA: Clostridium chauvoei-positive

Chemistry abnormalities:

[Ca] 6.5 (7.4-11.5 mg/dl); total protein 5.8 (6.5-9.3 g/dl); albumin 2.6 (3-4 g/dl); aspartase aminotransferase 1420 (53-173 U/L); creatinine kinase >16,000 (55-392 U/L); anion gap 21.9 (10-18 mmol/L); fibrinogen 1000 (300-700 mg/dl); leucopenia [WBC] 3800 (4000-12,000).

Cytology:

Smear from a left thigh aspirate: Low cellularity with few, intact, nucleated cells and numerous erythrocytes in a light pink hazy background with many, thick, box-like, bacterial rods often seen in end-to-end pairs. The nucleated cell population is composed of non-degenerate neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes in numbers and proportions consistent with peripheral blood. No overtly neoplastic cells are observed.

Skeletal muscle FA: Clostridium chauvoei-positive

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

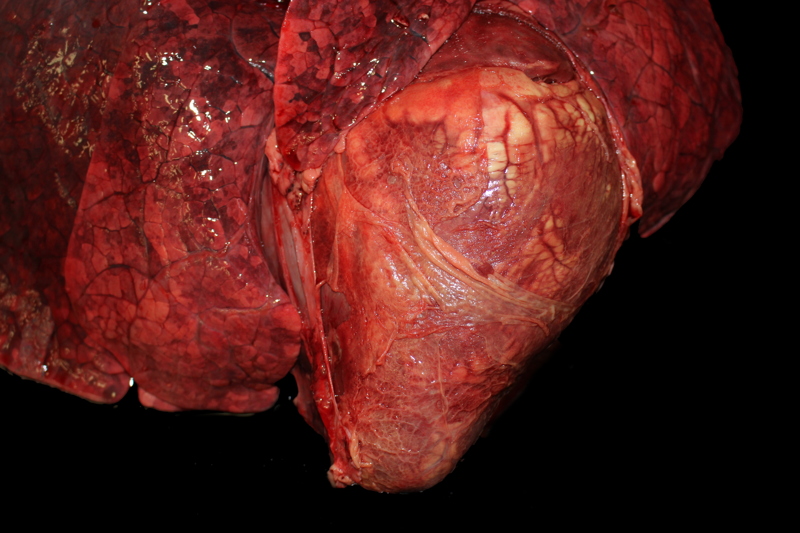

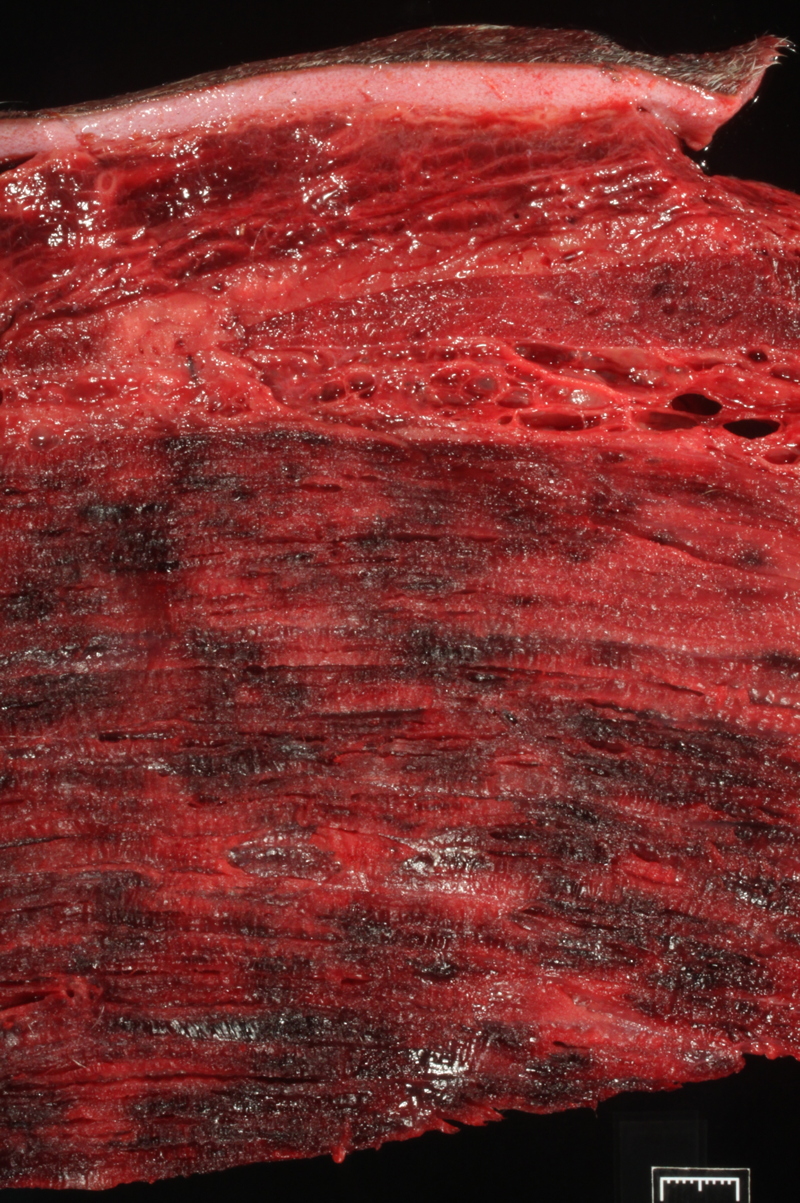

This cow's heart had a fibrinosuppurative epicarditisand when the heart was sectioned, the necrohemorrhagic myocarditis was noted to penetrate the myocardium. Visceral lesions may be small and are missed in cursory necropsies. It is important to note that the visceral sites are heavily used muscle sites, predisposed to having a lower pO2. Diagnosis in this case was straight-forward because the carcass was fresh, and only C. chauvoei was seen with the FA test; however, C. chauvoei does not proliferate post-mortem,7 and in autolized carcasses, other clostridial species may grow. In making a clostridial diagnosis, four basic aspects/criteria should be considered:1 a) clinical history, b) post-mortem findings, c) relative numbers of pathogenic organisms seen in the microscopic fields, and d) the postmortem interval. If animals are id-entified early and treated with antibiotics, they will live several hours longer and will have fibrinous and hemorrhagic transudates covering the pleura, pericardium and pe-ritoneal surfaces (contributor's observation). Such a pleuritis without pneumonia is common with blackleg.

Outbreaks of clostridial myocarditis caused by C. chauvoei are reported in calves and sheep.3,8 In ruminants, other causes of nec-rosuppurative (non-traumatic) myocarditis are Histophilus somni and listeriosis.5

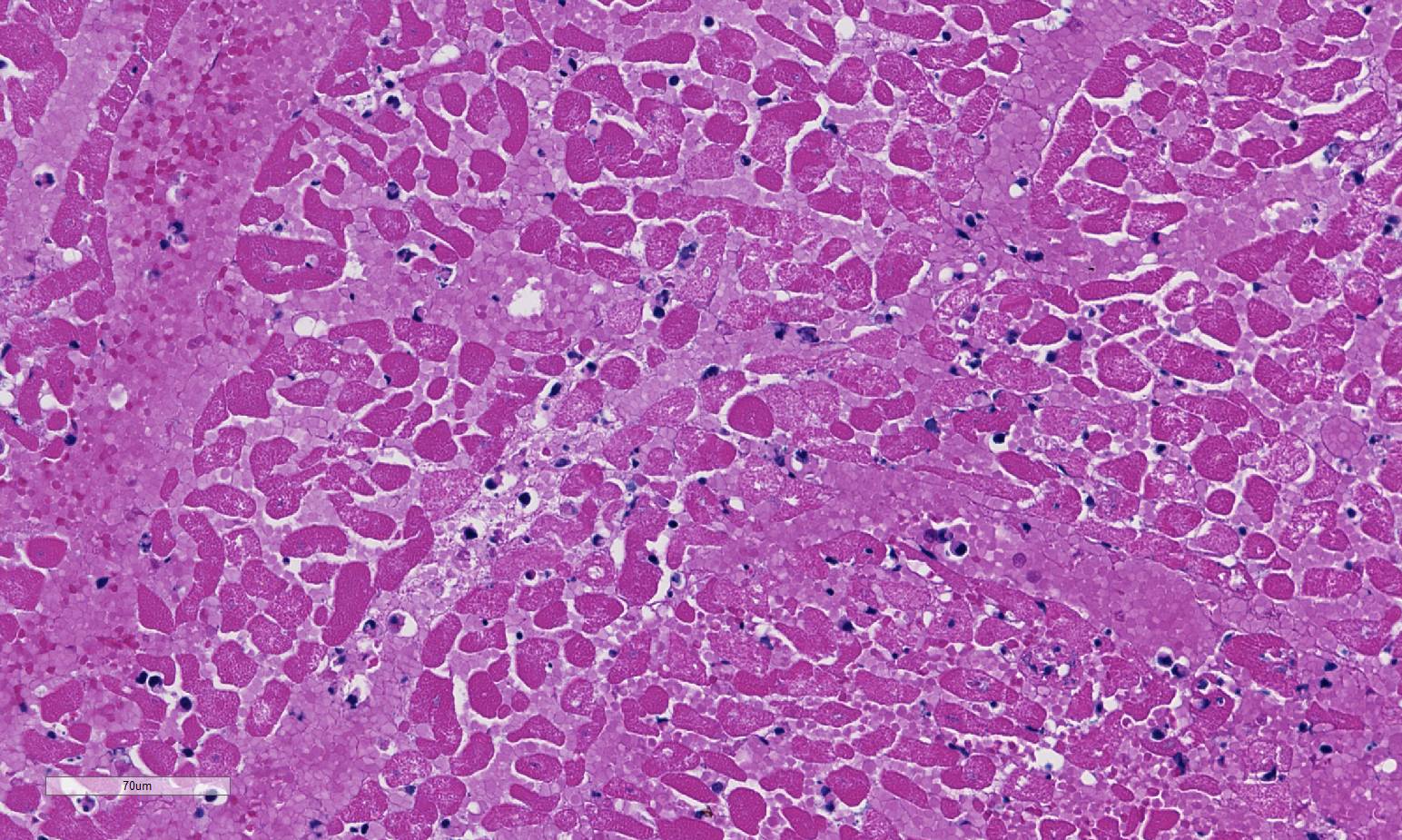

Sarcocystis (Sarcocystis cruzi or S. hirsuta) are ubiquitous in cattle muscles, and as seen in this case, the sarcocyst full of bradyzoites does not incite a host response except in cases of eosinophilic myositis.5

JPC Diagnosis:

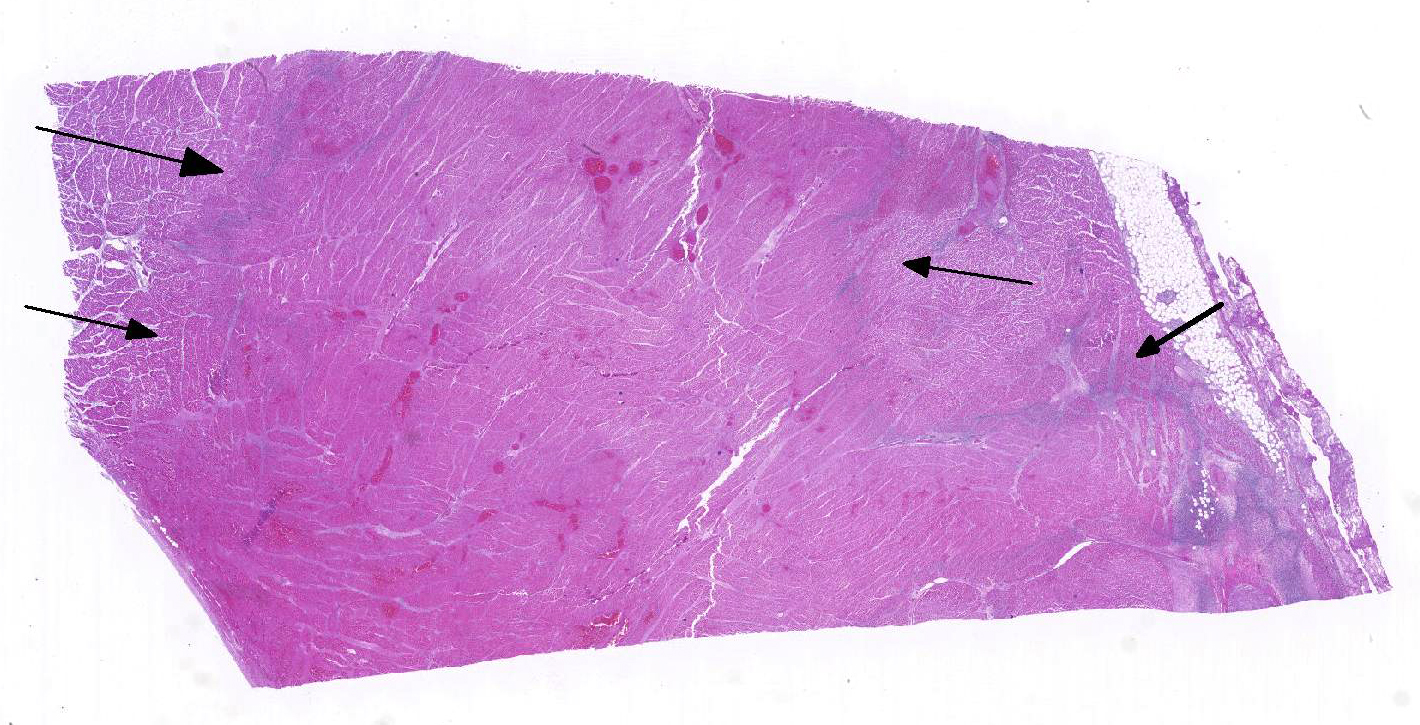

1. Heart: Pancarditis, necrosuppurative and fibrinous, acute, diffuse, severe with necrotizing vasculitis, fibrin thrombi and moderate numbers of bacilli.

2. Heart, myocardium: Sarcocysts, few.

Conference Comment:

Other clostridial agents cause disease in a fashion similar to Clostridium chauvoei, including C. septicum, the agent of pseudoblackleg and a potential etiology of malignant edema. As opposed to ingestion, spores of C. septicum are often encountered via wound infection. Spores germinate in the anaerobic environment created in the wound, releasing toxins which cause muscle damage similar to what is seen in blackleg.11 Other agents of malignant edema include C. sordelli and C. novyi. Malignant edema also has a similar pathogenesis to big head in sheep where wounds of the head sustained during fighting allow germination of Clostridium novyi spores followed by release of toxins similar to what is described for blackleg and malignant edema. This results in significant edema in the head and neck region and may extend into the thorax. In black disease, ingested C. novyi spores are present in the liver and fluke migration establishes the anaerobic environment needed for spore germination resulting in extensive hepatic necrosis.11

Conference participants commented that although emphysema is commonly seen in this entity, and was present in the excellent gross image provided by the contributor, it is not a prominent histologic finding in the slides provided. Conference participants also noted necrotizing vasculitis as a feature in this case, although it is typically not associated with this entity,10 as well as the presence of fibrin thrombi variably filling vessel lumina and adhering to vessel walls. A tissue Gram stain highlighted bacilli in this slide.

The decreased calcium level in this case is the result of entry of calcium into damaged muscle cells. Albumin is a negative acute phase protein and is decreased in cases of acute inflammation. The increased anion gap is likely due to a combination of lactic acidosis and elevation of renal acids se-condary to dehydration. Elevations in as-partase aminotransferase and creatinine kinase are secondary to muscle damage. Other agents which may cause necrotizing myositis / myocarditis and were discussed during the conference include Trueperella pyogenes which typically results in abscesses and Bacillus anthracis which results in the presence of abundant dark, unclotted blood exuding from multiple orifices. Other differential diagnoses dis-cussed include ionophore toxicity, vitamin E /selenium deficiency and eosinophilic myositis.

References:

1. Batty I, Kerry JB, Walker PD. The incidence of Clostridium oedematiens in post-mortem material. Vet Rec. 1967; 80: 32.

2. Casagrande RA, Pires PS, Silva ROS, Sonne L, Borges JBS, et al. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and biomolecular diagnosis of myocarditis due to Clostridium chauvoei in a bovine. Ciencia Rural. 2015; 45:1472-5.

3. Glastonbury JRW, Searson JE, Links IJ, Tuckett LM. Clostridial myocarditis in lambs. Aust Vet J. 1988 65:208-209.

4. Malone FE, McFarland PJ, O 'Hagan J. Pathological changes in the pericardium and meninges of cattle associated with Clostridium chauvoei. Vet Rec. 1986; 118: 151-2.

5. Maxie MG, Robinson WF. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG. ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer 's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th edition. Saunders Elsevier: New York; 2007: 41-2.

6. Sojka JE, Bowersock TL, Parker JE, Blevins WG, Irigoyen L. Clostridium chauvoei myositis infection in a neonatal calf. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992; 4:201-3.

7. Thompson K. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer 's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th edition. Saunders Elsevier: New York; 2007:261-4.

8. Uzal FA, Paramidani M, Assis R, Morris W, Miyakawa MF. Outbreak of clostridial myocarditis in calves. Vet Rec. 2003; 152:134-6.

9. Useh NM, Nok AJ, Esievo KAN. Pathogenesis and pathology of blackleg in ruminants: the role of toxins and neuraminidase A short review. Vet Q. 2003; 25(4):155-159.

10. Valentine BA, McGavin MD. Skeletal muscle. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:907.

11. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:195-197.