Signalment:

Gross Description:

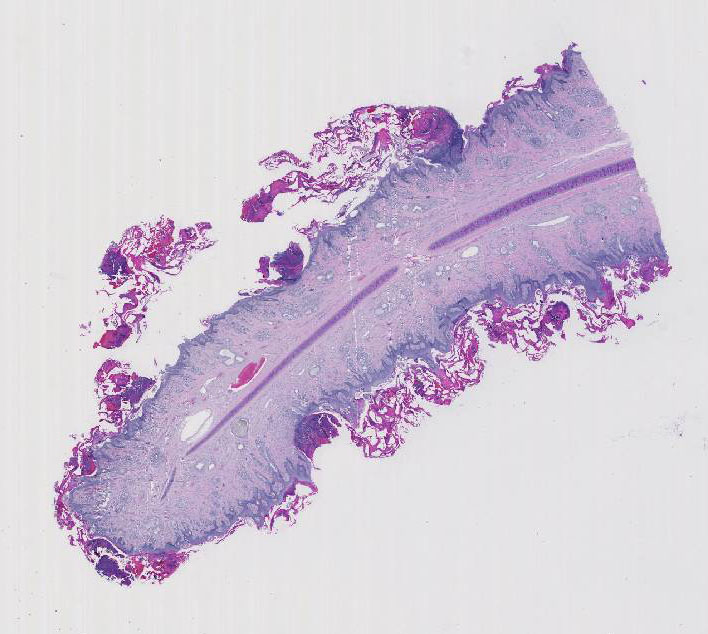

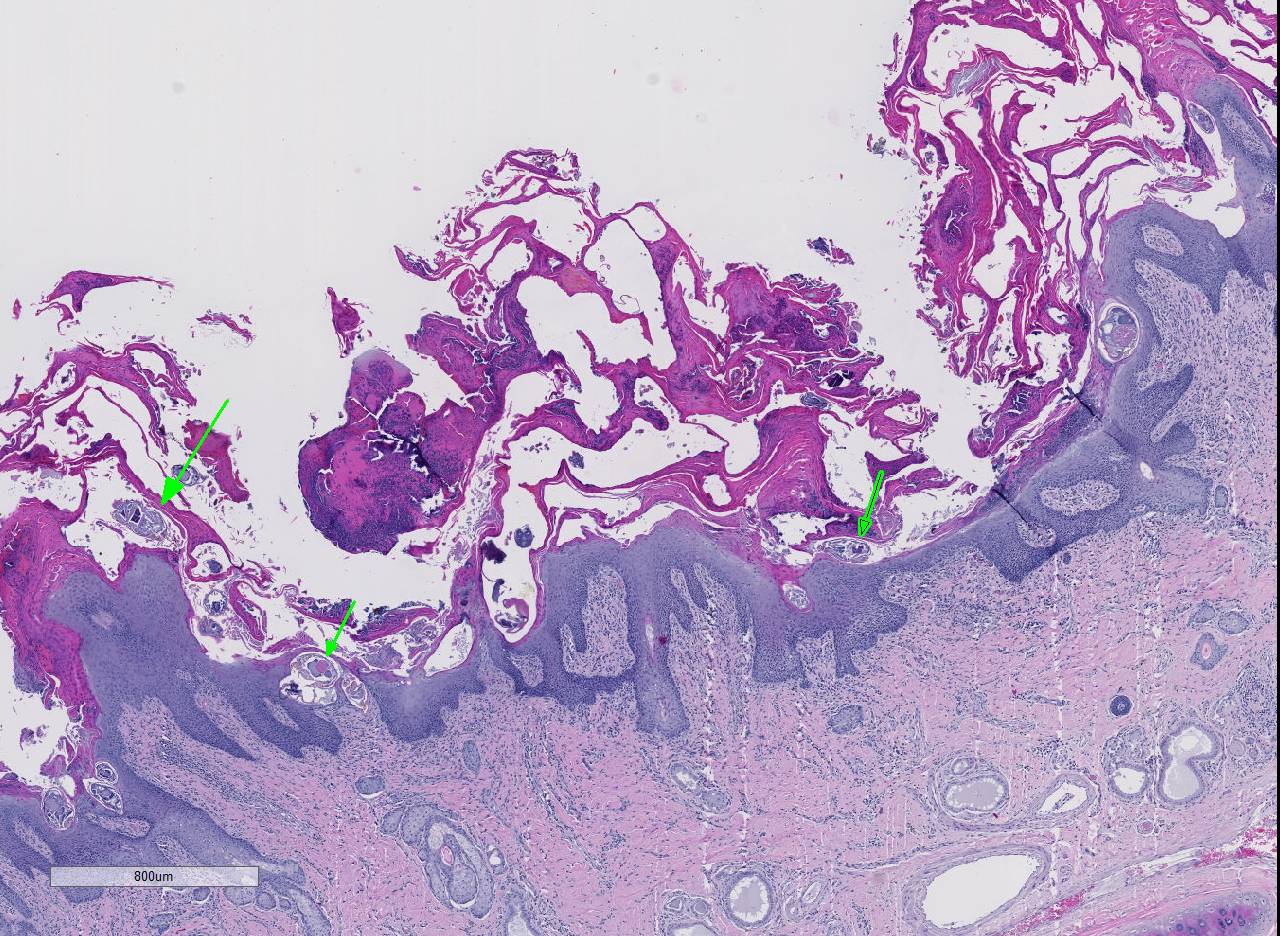

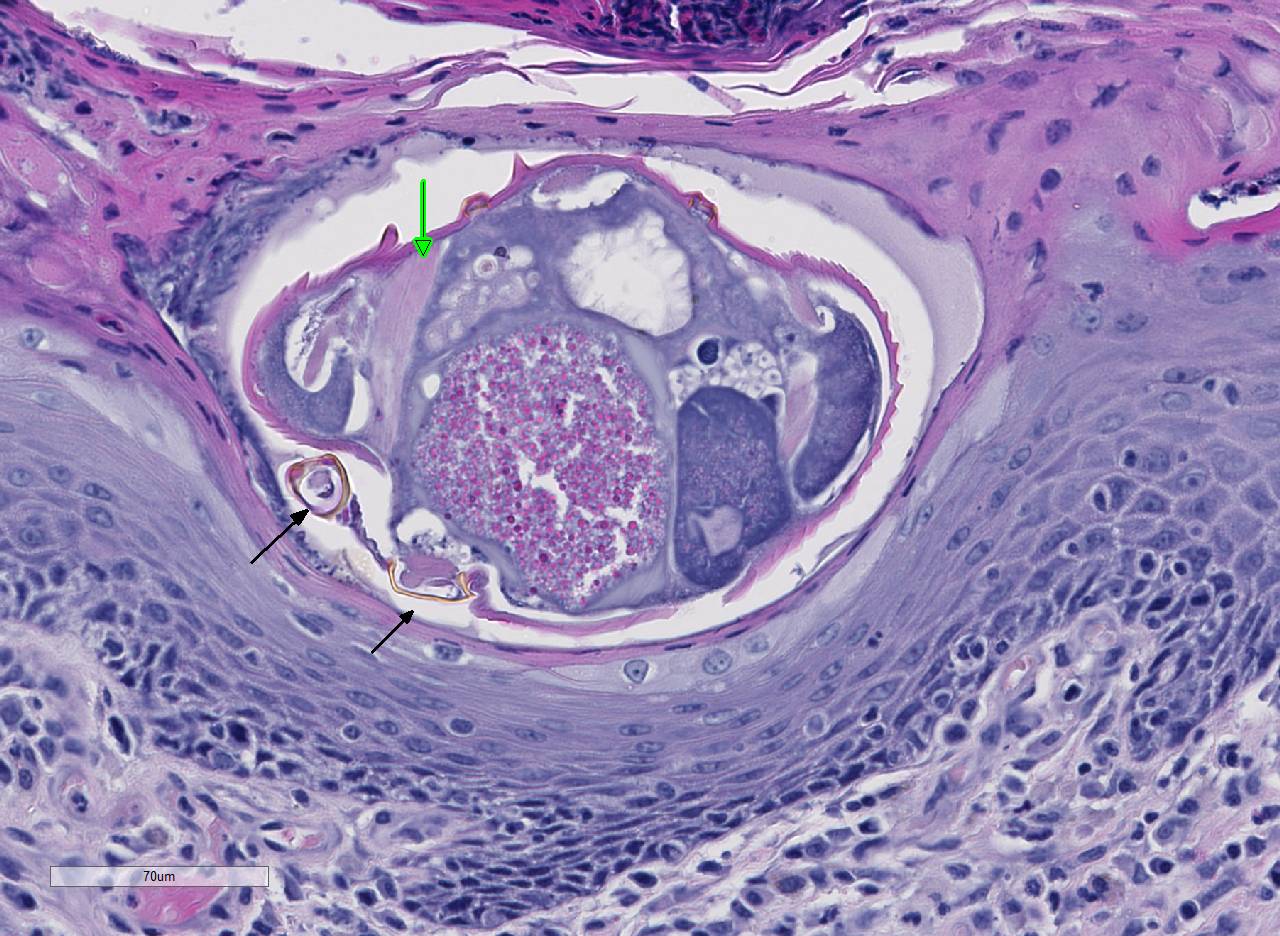

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Epizootics of sarcoptic mange caused by Sarcoptes scabiei in coyotes have been reported in Montana, Alberta, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New York, Kansas, Texas, Louisiana and South Dakota. Reports of mangy coyotes in south Texas go back to the 1920s. Adult males and particularly transient coyotes are significantly more likely to be infected. Severely affected animals have significantly less body fat. Infected individuals may be listless, show less fear of humans and are significantly more likely to seek shelter or food near human settlements. Mortality rates are higher in infected individuals; however, in southern climates, mange has not been shown to directly cause death.2,8,9

The myth of El Chupacabra appears to have arisen in Puerto Rico in the early 1990s and spread from there to South America, Mexico and the southern United States. Originally described as being ~3 feet tall with dorsal spines, leathery skin, a kangaroo-like posture, fangs and a forked tongue, the legend has morphed to include creatures resembling leathery dogs with pronounced spinal ridges and eye sockets. Be it the work of vampires, sadists, Santaría cultists or drug lords, chupacabra has provided a mythical explanation for unusual deaths of animals and humans.

The altered appearance and increased human contact of affected coyotes (the only animals identified as chupacabras and examined thus far in a scientific fashion) with sarcoptic mange provides a diagnosis, albeit banal, for the chupacabra phenomenon. Deflating the myth, it is hard to tell your kids that, a mangy coyote will come after you if you dont do your homework or eat your supper.

JPC Diagnosis:

2. Lymph node, paracortex: Plasmacytosis, marked.

Conference Comment:

Recently, there has been a suspected increase in host range of this ectoparasite with subsequent global diversification.3,7 As a result, S. scabiei has been introduced to novel species, likely due to increased human interaction.7 Most severely affected are the wild canids such as coyotes, red foxes, and grey wolves in North America; the southern hairy-nosed wombat in Australia; and the chamois, red deer, roe deer, and ibex in Europe. The introduction of this pathogen into new locations and hosts has been shown to produce high morbidity and mortality in these species.3,6,7

The pathogenesis involves direct damage due to the burrowing mite, irritation from mite excretions, and hypersensitivity to mite antigens in the cuticle, saliva, and feces. This leads to both an immediate (type I) and delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction causing an intense pruritus and alopecia.2,4,5,6 Pruritus causes decreased food intake (or ability to catch prey), dehydration, and severe weight loss along with secondary bacterial or fungal dermatitis. Eventually, animals succumb to the emaciation and dehydration if not properly treated. Poorly nourished or immunosuppressed animals develop massive mite burdens known as Norwegian type scabies.4,5,6

Conference participants noted several examples of female mites burrowing into and under the stratum corneum forming molting pockets in the skin where the female will mate and lay eggs.4 Interestingly, many had difficulty finding eggs within their sections despite the presence of numerous molting pockets. Conference participants also discussed other types of burrowing mites that affect veterinary species such as Notoedres sp. and Knemidocoptes sp.6 Additionally, participants noted mild reactive lymphoid hyperplasia with paracortical plasmacytosis in the adjacent lymph node. This reaction is relatively mild and likely related to chronic inflammation.

References:

2. Bornstein S, Morner T, Samuel WM. Sarcoptes scabiei and sarcoptic mange. In: Samuel WM, Pybus MJ, Kocan AA eds. Parasitic Disease of Wild Mammals. 2nd ed, Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2001:107-119.

3. Fraser T, Charleston M, Martin A, et al. The emergence of sarcoptic mange in Australian wildlife: An unresolved debate. Parasit Vectors. 2016; 9:316.

4. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing Professional; 2005:216-219.

5. Hargis AM, Ginn PE. Integument. In: McGavin MD, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier; 2012:1042- 1045.

6. Mauldin E, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier; 2016:673-680.

7. Murray M, Edwards M, Abercrombie B, St. Clair C. Poor health is associated with use of anthropogenic resources in an urban carnivore. Proc Biol Sci. 2015; 282(1806):20150009.

8. Pence DB, Ueckerman E. Sarcoptic mange in wildlife. Rev Sci Tech. 2002; 21:385-398.

9. Pence DB, Windberg LA, Pence BC, Sprowls R. The epizootiology and pathology of sarcoptic mange in coyotes, Canis latran, from South Texas. J Parasitol. 1983; 69:1100- 15.

10. Pence DB, Windberg LA: Impact of a sarcoptic mange epizootic on a coyote population. J Wildlife Mgmt. 1994; 58:624-633.