WSC 2022-2023

Conference 25

Case III:

Signalment:

11-month-old female spayed Golden Retriever (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

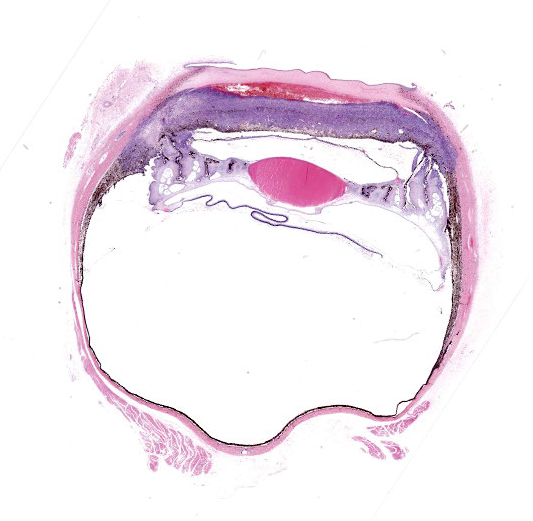

Female, spayed, Golden Retriever presented with chronic anterior uveitis, possible vitritis, possible iris mass, and secondary glaucoma in the right eye. The right eye is blind; thus, removal with histopathology of the right eye was elected.

Gross Pathology:

Uveitis with secondary glaucoma

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

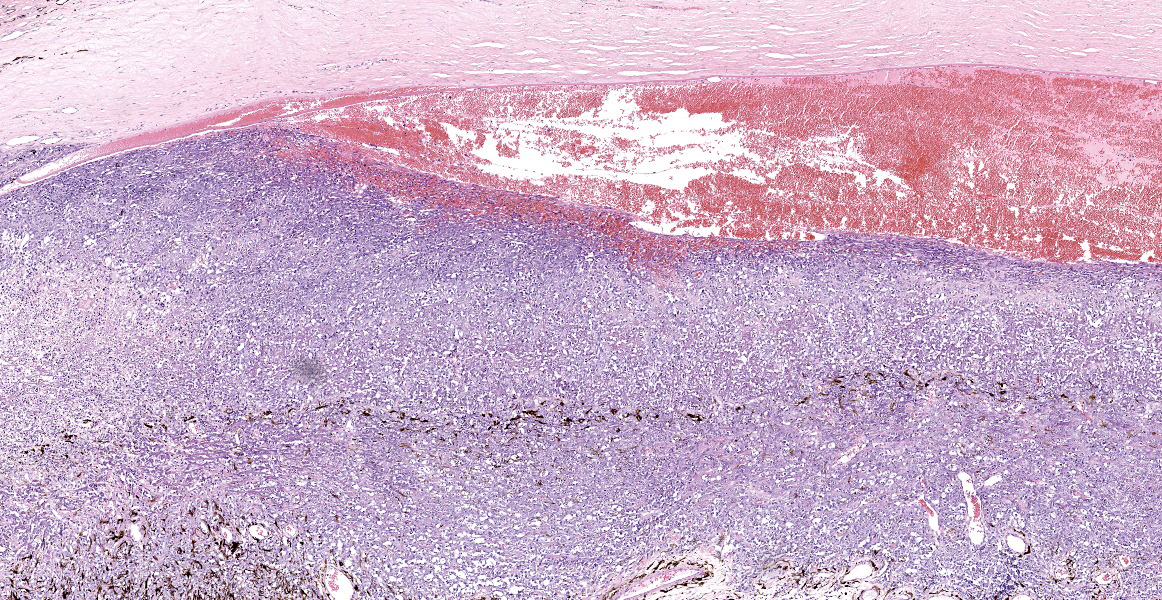

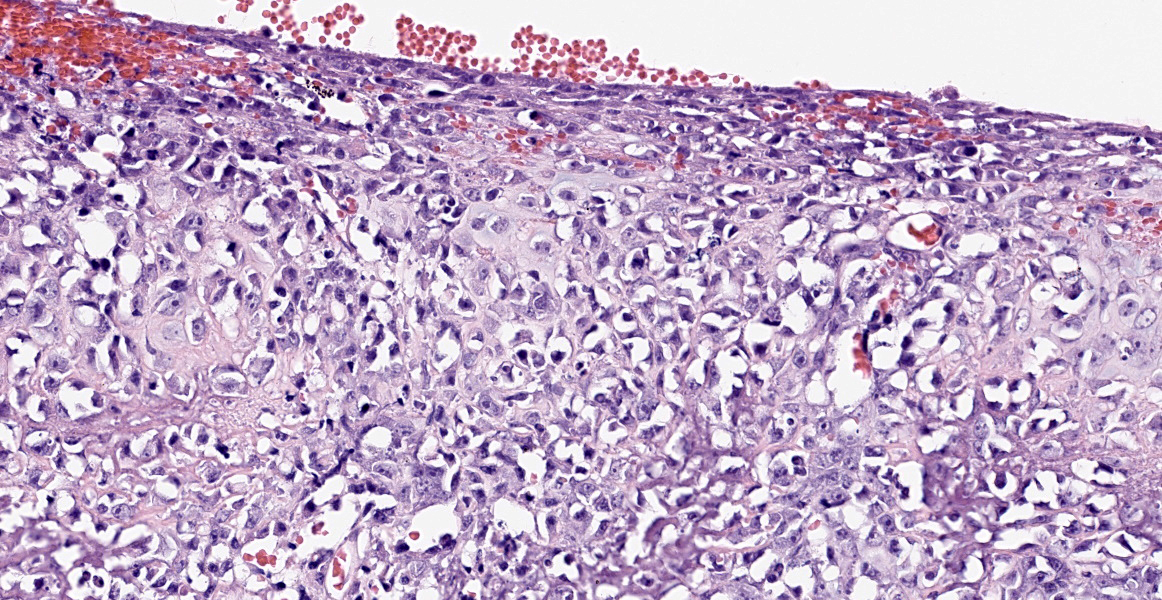

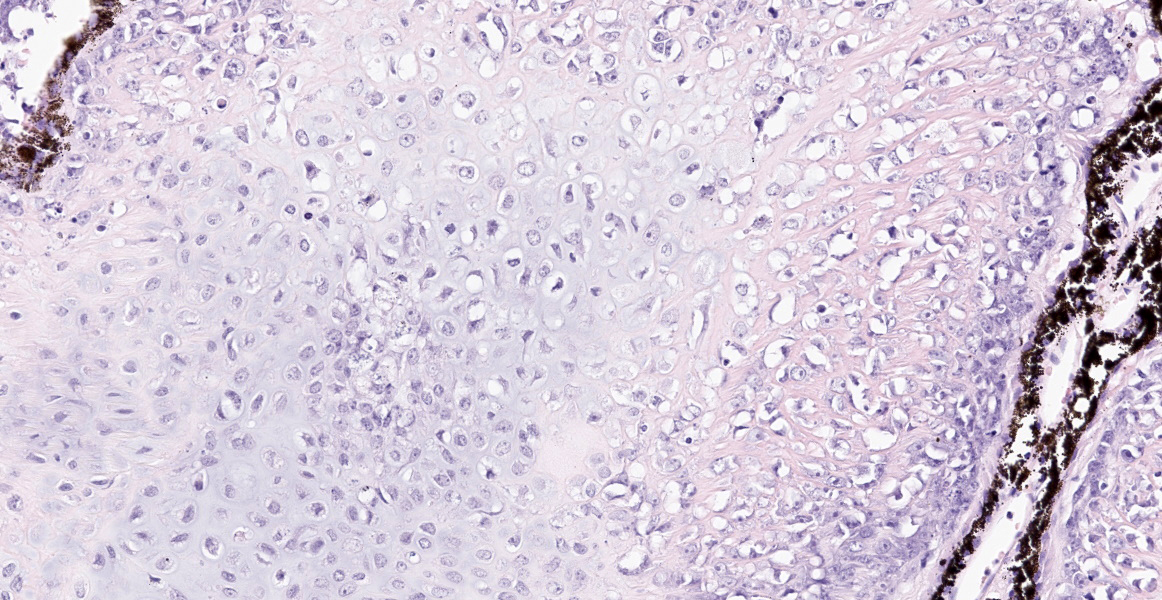

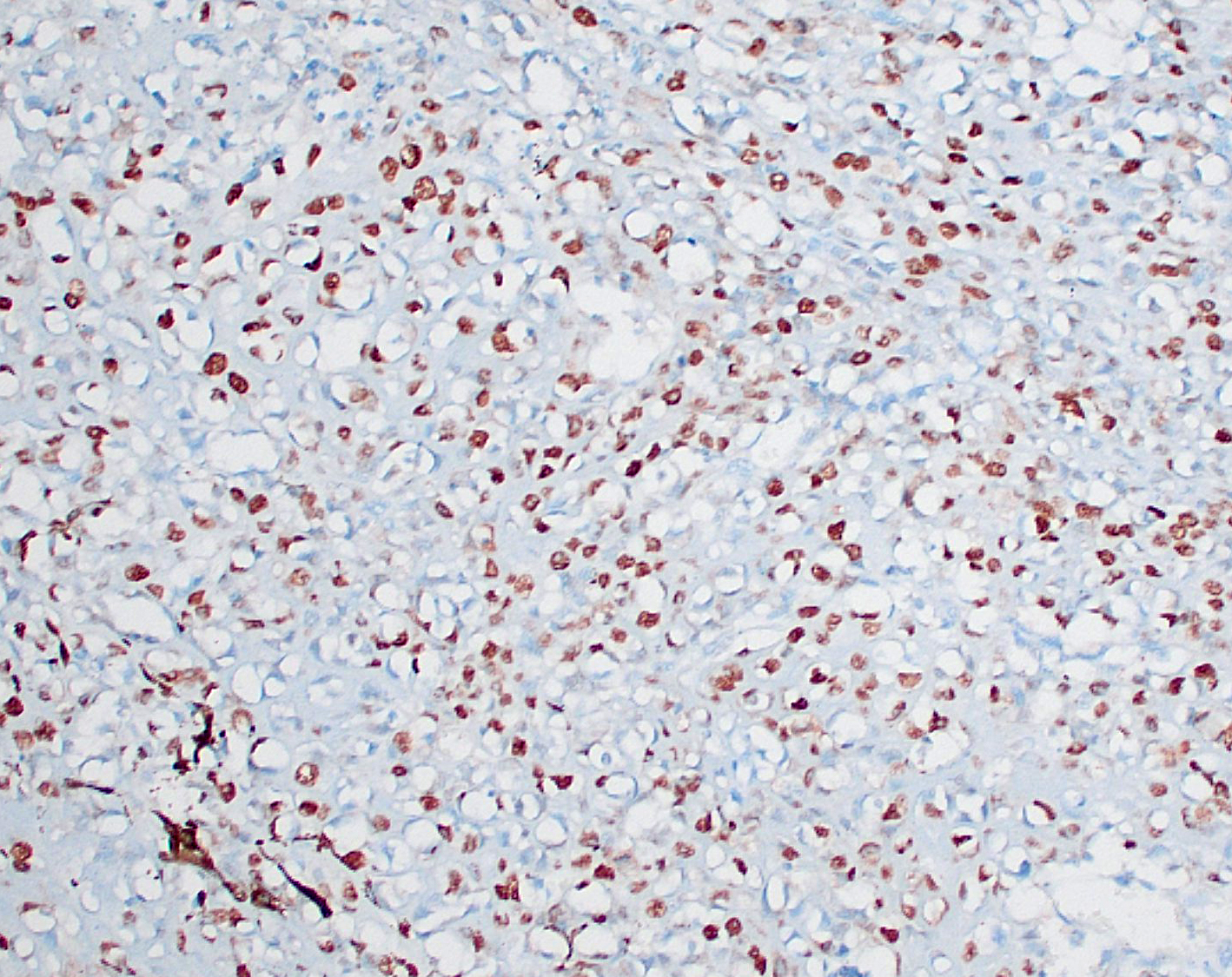

Right eye: Within the cornea, there is a small number of small-caliber vessels originating from the limbus and coursing through the peripheral stroma (neovascularization). The anterior chamber contains a large amount of hemorrhage (hyphema) admixed with eosinophilic homogneous to polymerized material (proteinaceous fluid) and small numbers of polymorphonuclear cells. The iris, iridiocorneal angle, and ciliary body are markedly expanded and almost completely effaced by an unencapsulated, poorly demarcated, infiltrative, densely cellular mass. The mass is composed of pleomorphic neoplastic spindle to oval cells arranged in extensive sheets supported by a moderate amount of fibrous to collagenous matrix. Multifocally, the neoplastic cells are separated and lined upon, small, thin trabecula composed of deeply eosinophilic granular to glassy extracellular material (osteoid) that is variably mineralized. Multifocally, neoplastic cells are present in lacuna and are embedded within a basophilic matrix (cartilage matrix). Neoplastic cells have a moderate amount of cytoplasm, variably discernible cell boundaries, a large oval nucleus with stippled chromatin, and 1-4 prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells demonstrate marked anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and have a high mitotic index (20 per ten 0.237mm2 fields). 50-60% of the mass is lack differential staining (coagulative necrosis) or a complete loss of cellular architecture with replacement by eosinophilic karyorrhectic and cytolytic cellular debris (lytic necrosis). The iris is multifocally adhered to the anterior lens capsule (posterior synechia). The iridocorneal angle is collapsed and effaced by neoplastic cells. The ciliary body is mostly effaced by neoplastic cells and neoplastic cells are observed extending up the Zonules of Zinn to the lens capsule. There is a distinct layer of fibrous connective tissue extending from the surface of the ciliary body over the posterior lens capsule (cyclitic membrane). The non-tapetal retina is diffusely thin with marked hypocellularity of all layers, especially the ganglion and inner nuclear layers (retinal degeneration). The tapetal retina is somewhat spared, but there is hypocellularity of the ganglion and inner nuclear layer (ganglion cell layer degeneration). There are aggregates or emboli of neoplastic cells and necrotic cell debris within the scleral veins (vascular invasion).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Right eye: Osteoblastic osteosarcoma, anterior uvea, with neovascularization, hyphema, cyclitic membrane, secondary glaucoma, and retinal degeneration, Golden Retriever, Canis lupus familiaris, canine

Contributor’s Comment:

Osteosarcoma is the most common tumor of the appendicular skeleton in dogs and cats.10 They are locally invasive and readily metastasize to the regional nodes and elsewhere, especially lungs. Extraskeletal osteosarcomas are less common and occur in soft tissue and visceral organs, without any primary bone involvement.9 Organs commonly affected are the adrenal gland, kidney, mesentery, ileum, liver, spleen, reproductive organs, and the eye.8 Osteosarcoma in the eye, as a primary process, occurs with even more rarity in dogs and cats.1,5 This ocular tumor has been reported most in large breed dogs between the age of 9 - 11.5 years.5 Common clinical signs include exophthalmos5, hyphema, and blepharospasm.11

Histologically, extraskeletal osteosarcomas appear similar to other skeletal osteosarcoma.7 Within the eye, the tumors are observed in the iris and ciliary body. Tumors are composed of pleomorphic spindle cells or stellate cells, with occasional multinucleated cells resembling osteoclasts, in an abundant extracellular collagenous matrix (osteoid).5,11 Anaplastic osteoblasts are characteristic of osteoblastic osteosarcoma2, such as in this case. Other nuclear characteristics include hyperchromic, often eccentric nuclei with varying amounts of basophilic cytoplasm.3 Osteoblastic osteosarcomas are further characterized into ‘productive’ or ‘non-productive’ osteosarcoma to indicate the amount of bone production: minimal, lacy strands, irregular islands, and larger accumulation.3 In dogs, the most common subcategory of skeletal osteosarcoma is moderately productive osteoblastic osteosarcoma.3 Only one small scale study noted osteoblastic osteosarcoma as being the most frequent type of extraskeletal osteosarcoma in the dog, but was not further subcategorized.8

Similar to humans, extraskeletal osteosarcomas are highly malignant, and metastasis is common. However, this occurs less often to the lungs when compared to skeletal osteosarcomas.9 Decreased survival times result from late detection of tumors and restricted surgical resection of tumors from some sites.9

In comparison, ocular osteosarcomas in cats can arise after trauma to the eye.12 Feline post-traumatic osteosarcoma can occur several months to several years after penetrating injury to the eye. The tumor starts at the lens and progresses towards lining the interior of the eye. It then extends to the scleral venous plexus or optic nerve10, to diffusely affect the globe.4,11 The lining of the eye by the tumor is a key feature in differentiating metastatic osteosarcoma vs. primary ocular osteosarcomas. Metastatic rates in these feline cases have occasionally been documented to be 60% with metastasis reaching the brain even post enucleation.12

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology

College of Veterinary Medicine

Iowa State University

Ames, Iowa 50010-1250

https://vetmed.iastate.edu/vpath

JPC Diagnosis:

Eye, anterior uvea and sclera: Osteosarcoma.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor mentions, primary intraocular osteosarcoma is rare in veterinary species and has been reported in dogs, cats, a cockatoo, and most recently, a rabbit. Makishima et al. described a primary intraocular osteosarcoma in an 8-year-old lop-eared rabbit. The animal had a history of cataracts, glaucoma, and posterior lens luxation in the left globe several years prior to the development of osteosarcoma. The neoplasm created significant exophthlamos and effaced almost the entire globe, extended beyond the sclera in the retrobulbar space, but did not invade the optic nerve or surrounding tissues. There was no evidence of metastasis, and the animal died due to respiratory failure caused by pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors.8

Primary appendicular osteosarcoma can be difficult to differentiate histologically from other primary bone tumors, including chondrosarcoma and fibrosarcoma. One key histologic feature considered diagnostic for osteosarcoma is the presence of osteoblasts producing osteoid. In equivocal cases, immunohistochemistry may be required to differentiate these bone tumors, and a recent study evaluated several markers with varying historical utility in osteosarcoma: alkaline phosphatase (ALP), runx2, osteonectin (ON), and osteopontin (OP). All four markers were found to be very sensitive for osteosarcoma, but specificity varied. The study authors found that ALP, which has the highest sensitivity but low specificity, is best used as an initial screening test, and runx2, an osteoblast transcription factor with highest specificity of the four markers, should be run on ALP-positive sections. Combining these two tests in parallel provided 87% sensitivity and 85% specificity in canine appendicular osteosarcomas.2

The moderator discussed how the presence of neoplastic cells within the scleral vessels adjacent to the trabecular meshwork is likely due to passive drainage and not necessarily indicative of primary vascular invasion. Additionally, differentiation between primary and metastatic neoplasia in this case cannot be done histologically and requires correlation with clinical findings. Historically, the lung has been the most common site for osteosarcoma metastasis, but the moderator also discussed that, anecdotally, oncologists are seeing an increased number of osteosarcoma metastasis to atypical sites. This may be due to prolonged survival times with advances in tumor treatment.

References:

- Attali-Soussay K, Jegou JP, Clerc B. Retrobulbar tumors in dogs and cats: 25 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 2001;4: 19-27.

- Barger A, Baker K, Driskell E, et al. The use of alkaline phosphatase and runx2 to distinguish osteosarcoma from other common malignatn bone tumors in dogs. Vet Pathol. 59(3): 427-432.

- Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson KG. Bones and Joints: Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of bones. In: Jubb K, Kennedy P, Palmer N, eds. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:110-116.

- Dubielzig RR, Ketring K, McLellan GJ, Albert DM. Non-surgical trauma. In: Dubielzig RR, Ketring K, McLellan GJ, Albert DM, eds. Veterinary Ocular Pathology. Edinburgh: W.B. Saunders; 2010:103,111.

- Heath S, Rankin AJ, Dubielzig RR. Primary ocular osteosarcoma in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol. 2003;6: 85-87.

- Hendrix DV, Gelatt KN. Diagnosis, treatment and outcome of orbital neoplasia in dogs: a retrospective study of 44 cases. J Small Anim Pract. 2000;41: 105-108.

- Labelle AL, Labelle P. Canine ocular neoplasia: a review. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2013;16: 3-14.

- Makishima R, Kondo H, Naruke A, Shibuya H. Intraocular extraskeletal osteosarcoma in a rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J Vet Med Sci. 2020; 82(8): 1151-1154.

- Patnaik AK. Canine extraskeletal osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Veterinary pathology. 1990;27: 46-55.

- Thompson KG, Dittmer KE. Tumors of Bone. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:329.

- van de Sandt RROM, Boevé MH, Stades FC, Kik MJL, Kirpensteijn J. Intraocular osteosarcoma in a dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 2004;45: 372-374.

- Wilcock BP, Njaa BL. Special Senses. In: Jubb K, Kennedy P, Palmer N, eds. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016.