WSC 2022-2023

Conference 24

Case II:

Signalment:

12-year-old, male, mixed breed, dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

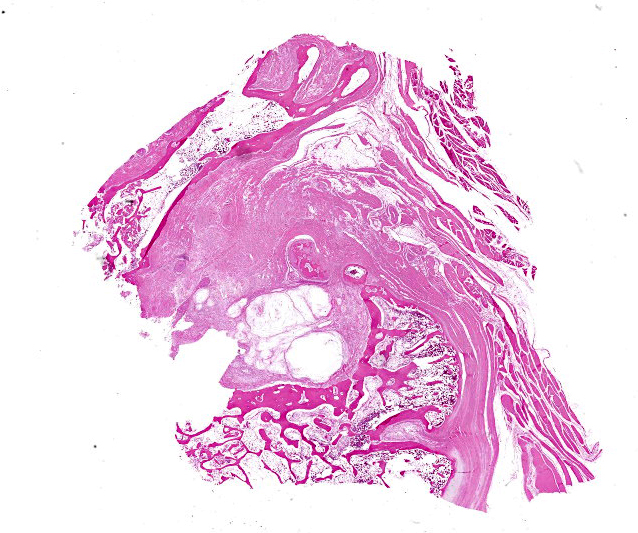

Left shoulder pain for 1 year. Radiographs show marked proliferation of bone around the shoulder joint involving, among other, the glenoid cavity, the head of the humerus and the greater tubercle. The limb was amputated.

Gross Pathology:

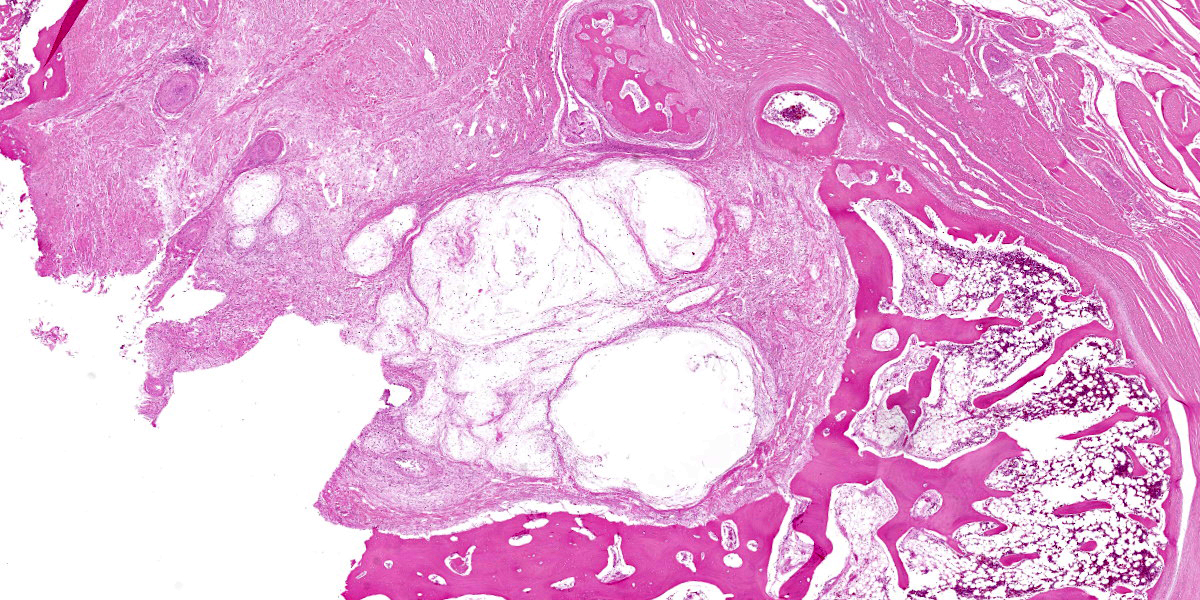

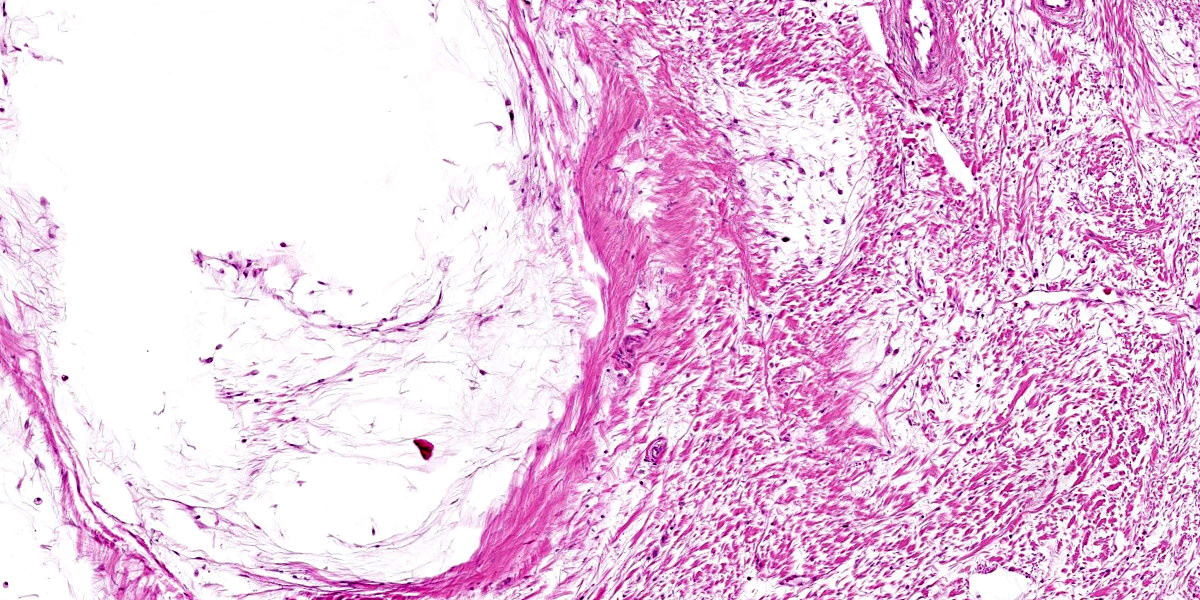

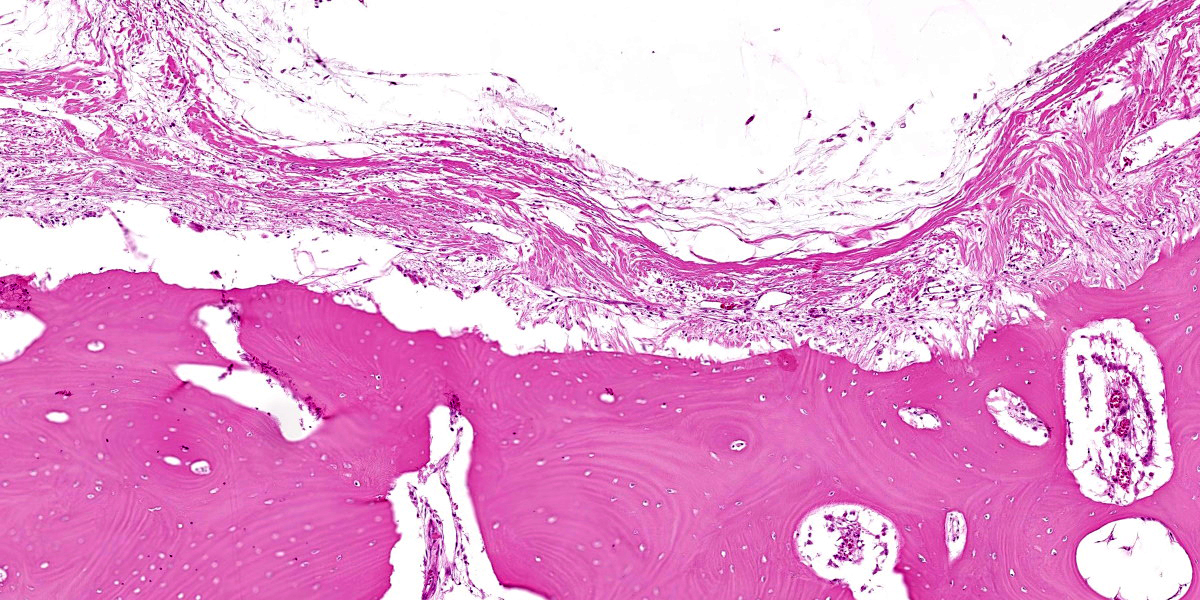

The specimen received was approximately 15cm in diameter. It was rigid and consisted of bone covea In slide A, polygonal cells of uncertain identity are attached to the inner aspect of the pseudocyst (histiocytes? synoviocytes? other mesenchymal cells?).

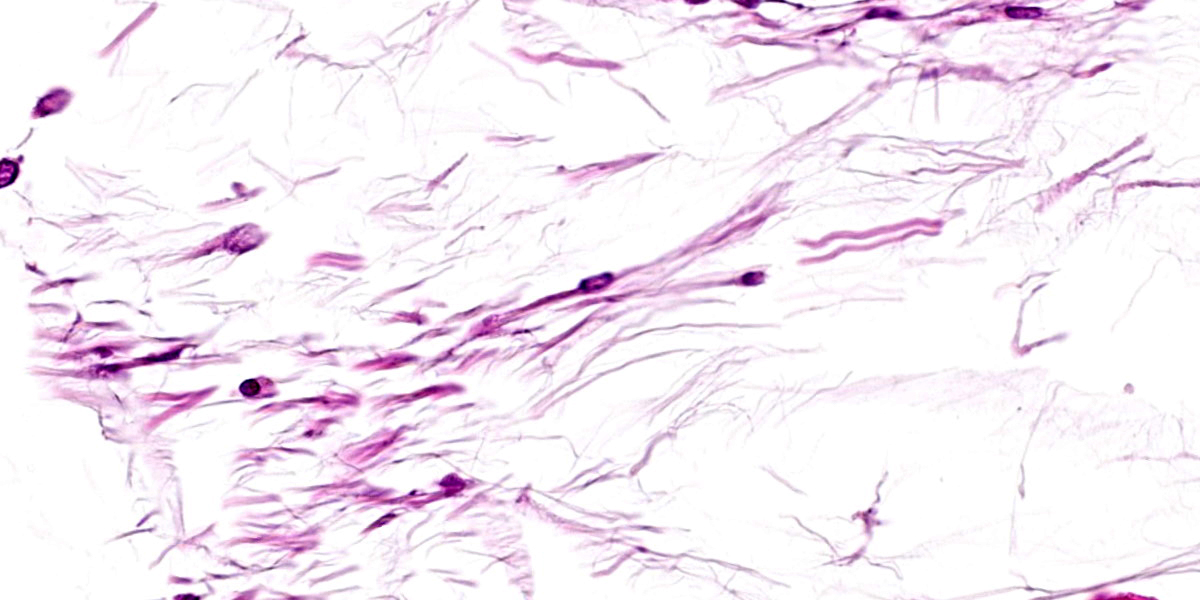

*Notes: In well stained samples from the same case, the nodules contain loose, lightly basophilic myxoid material (photos attached). The collections of shattered bone and other debris in the lumen are considered contaminants from sawing.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Synovial myxoma

Contributor’s Comment:

Synovial myxoma is the most common benign neoplasm in the joints of dogs.3 Its microscopic appearance is characteristic but because it is an uncommon tumor 86% of cases in one report were initially diagnosed as malignant.1 The tumor typically consists of variably sized nodules composed of a low number of stellates to spindle cells surrounded by abundant hypovascular myxoid matrix.1,3

The findings in a series of 39 cases indicate that large breed, middle-aged dogs, especially Doberman Pinschers and Labrador retrievers were commonly affected, and the stifle and digits were the most common sites. Survival times were long (average >2.5 years) even with incomplete excision. Three of 39 cases had local recurrence, but none metastasized or directly resulted in death.1 Whilst some cases are confined to the joint capsule, others are infiltrative and grow along fascial planes. This appears to be the case in the submitted slides in which the tumor is located near bone and not within the joint. In the series of 39 cases, bone invasion was seen in 8 dogs. The authors concede that bone invasion is not typical of benign tumors, but their rationale to use the same diagnosis for all cases was the similarity of the histologic features of the tumors, irrespective of the presence of bone invasion.1 Cases without bone lysis or expansion outside the joint capsule can be treated with synovectomy. Of cases confined to the joint capsule and treated with synovectomy, 10% recur.3 Cases with bone lysis cause significant pain and usually require amputation.3

The viscous fluid produced by these tumors suggests that they originate from type B (fibroblast-like) synoviocytes which produce synovial fluid,1 but this remains unproven as there are no reliable markers for this cell2 and the IHC results in the case series cited above showed significant positive staining for CD18, which is a marker for type A synoviocytes.1

Previous designations of this entity include myxoma of the synovium - the term used for this entity when it was first described by RR Pool in 1990 (in the 3rd edition of Meuten’s Tumors in Domestic Animals), myxosarcoma and nodular synovial hyperplasia.3

The submitted case is unusual in involving the shoulder, which was not affected in any case of the large case series.

The three most common tumors of the canine synovium are histiocytic sarcoma, synovial cell sarcoma, and synovial myxoma, with widely divergent prognosis. Because bone invasion may be present in synovial myxoma, the 3 tumors cannot be differentiated radiographically. Synovial myxoma can be identified by its characteristic histologic appearance. Immunohistochemistry can be used to differentiate synovial histiocytic sarcoma (cytokeratin negative, CD18 positive) - the most common malignant tumor from the synovial cell sarcoma (cytokeratin positive, CD18 negative), which is a controversial entity in animals.1,2

Contributing Institution:

The Weizmann Institute of Science

http://www.weizmann.ac.il/

JPC Diagnosis:

Joint capsule: Synovial myxoma.

JPC Comment:

A few reports of synovial myxomas with atypical presentations in dogs have been reported. Izawa et al describe a synovial myxoma with intramuscular infiltration as an incidental finding in a 16-year-old dog that was euthanized due to progressive renal failure. The dog had no clinical signs of lameness, and the tumor was only described when a jelly-like substance was discovered between skeletal muscles of the hind limb on necropsy.4 There were also multiple small translucent nodules in the stifle. Histologically, the nodules had the classic appearance of a synovial sarcoma, with few spindle to stellate cells embedded in abundant myxoid matrix, and similar nodules were identified in the jelly-like areas between muscles.4

Neary et al described a synovial myxoma associated with the cervical articular facet in a 12-year-old mixed breed dog. The animal presented with a two-week history of progressive neurologic deficits and tetraparesis, and the dog was successfully treated with a dorsal hemilaminectomy and facetectomy.6

Synovial myxomas were ecently described in cats as well. In a 2020 Vet Pathol article, Craig et al described synovial cystic and myxomatous lesions in 16 cats. Most (12) of the masses were located in the elbow, and in all cases, the masses were unilateral. Three cats had masses composed of cysts; two cats had masses composed of spindle cells on myxomatous matrix (myxoma); and 11 cats had a combination of cysts and myxoma. While most of the lesions increased with time, the lesion was not the cause of natural death or euthanasia in any of the cats. Since the majority of the cats in this study also had bilateral degenerative joint disease, the authors hypothesized that synovial cysts initially form due to increased articular pressure and herniation of synovium; myxomas then form when there is subsequent neoplastic transformation.2

A single report of a synovial myxoma has been published in a 5-year-old rabbit. The affected hind limb was amputated, and grossly, the neoplasm partially effaced the femur and stifle joint, elevating the patella and extending into the fascia between muscles. Histologically, the neoplasm had the classic features of myxoma and was frequently surrounded by reactive bone, fibrosis, or cartilage. The authors recommended using the term “infiltrative” as part of the diagnosis for such invasive tumors to provide a better description of the biologic behavior.5

References:

- Craig LE, Kirmer PM, Colley AJ: Canine Synovial Myxoma: 39 Cases. Vet Pathol. 2010, 47:931-936.

- Craig LE, Kirmer PM, O’Toole AD. Synovial Cysts and Myxomas in 16 Cats. Vet Pathol. 2020; 57(4): 554-558.

- Craig LE, Thompson KG: Tumors of Joints. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Wiley Blackwell. 2017; 345-347.

- Izawa T, Tanaka M, Aoki M, Ohahshi F, Yamate J, Kuwamura M. Incidental Synovial Myxoma with Extensive Intermuscular Infiltration in a Dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2012; 74(12):1631-3.

- Lohr CV, Hedge ZN, Pool RR. Infiltrative myxoma of the stifle joint and thigh in a domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). 2012; 147(2-3):218-222.

- Neary CP, Bush WW, Tiches DM, Durham AC, Gavin. Synovial myxoma in the vertebral column of a dog: MRI description and surgical removal. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2014; 50(3):198-202.