Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

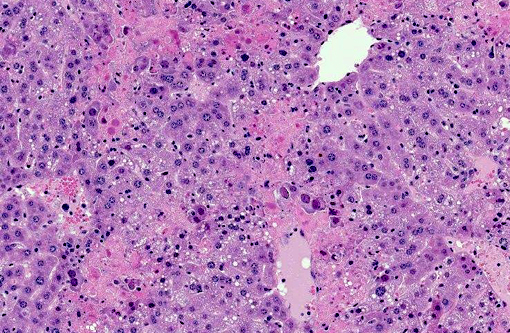

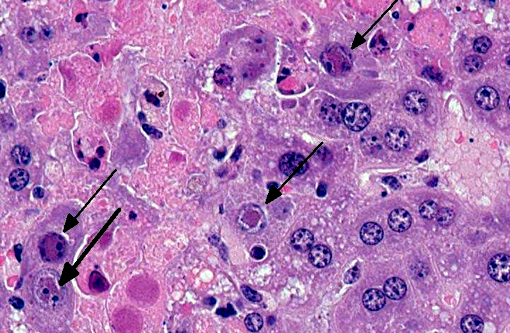

Liver Throughout the hepatic parenchyma there are randomly scattered foci of hepatocellular loss, and the tissue is replaced with amorphous eosinophilic material, often with remnant cellular outlines, and with pyknotic/karyorrhectic nuclei (acute necrosis). Associated with these foci, many of the nuclei of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells contain large, often well-demarcated bodies of deeply eosinophilic material with margination and blebbing of chromatin (intranuclear inclusions). Occasionally, small, discrete eosinophilic inclusions are also present in the cytoplasm. In the remaining tissue, the hepatocytes are generally swollen with microvesicular vacuolation (hydropic change).Â

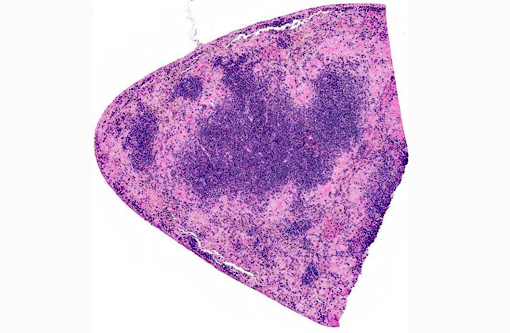

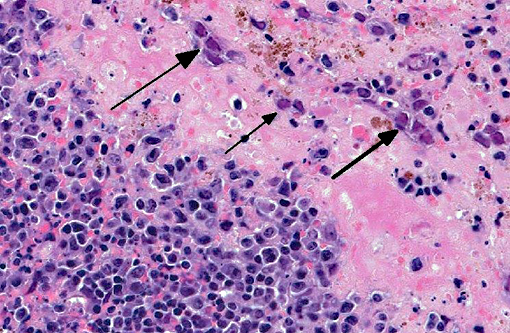

Spleen The reticuloendothelial cells of the red pulp are extensively lost and replaced by amorphous eosinophilic material and nuclear debris with little trace of the normal splenic architecture (acute necrosis). The remaining reticuloendothelial cells contain intranuclear inclusions as seen in the liver. The white pulp is relatively preserved, although many lymphocytes in the periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths, individually and in clusters, have shrunken, pyknotic nuclei.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Liver severe, acute, multifocal to coalescing hepatic necrosis with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions

- Spleen

- severe, acute, diffuse red pulp necrosis with intranuclear inclusions

- mild, acute, multifocal white pulp lymphoid necrosis

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Murine cytomegalovirus is a DNA virus in the family Herpesviridae, the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae, and the genus Muromegalovirus.(4) The betaherpesviruses are highly host specific viruses that infect humans, mice, rats and guinea pigs (and other mammals, though these are generally less well characterized). MCMV infections in mice have been extensively studied, largely because the course of infection in mice has several pertinent similarities to the course of Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection, making it a useful model to study the human disease. HCMV is a highly prevalent infection of humans worldwide, with seroprevalence in women of reproductive age varying from approximately 40% (US, much of western Europe, Australia) to >90% (Brazil, Chile, Italy, India, Turkey, Japan).(3) Infection rarely causes clinical signs in immunocompetent individuals. It is, however, a significant cause of morbidity in immunosuppressed individuals and is an important cause of disease (notably of hearing loss and neurological impairment) in children born to mothers who are first infected during pregnancy.(5)

As is typical of herpesviruses, MCMV causes lifelong, persistent infections with intermittent reactivation and virus shedding at times of host immunosuppression. After initial infection, MCMV replication occurs in salivary glands; excretion in saliva appears to be the primary means of transmission through grooming and biting activities. The virus then disseminates and severe infections may induce encephalitis, retinitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, myocarditis, adrenalitis and/or haemopoietic failure. Besides saliva, infective virus is also present in the tears, urine and seminal fluid of infected animals, though the occurrence of natural transmission by means of these secretions has not been well established. Viral DNA replication occurs in the nucleus of infected cells, while production of the capsid protein occurs in the cytoplasm. The capsid proteins are transported to the nucleus where viral packaging takes place; the packaged particles are then transported back to the cytoplasm where they acquire their primary envelope. A second enveloping stage is required before the virions are ready for release. Hence, infection is associated with both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions. The outcome of MCMV infection is highly dose-dependent in mouse models of infection, mortality may change from 0% to 100% with only a four-fold increase in dose. Other determinants of susceptibility include strain (BALB/C are highly susceptible; C57BL/6 are resistant) and age of the host (young animals are highly susceptible).Â

Investigations into the variable susceptibility of mouse strains to MCMV infection has shown that innate immune function, in particular the effectiveness of the natural killer (NK) cell response, is the key determinant of an animals capacity to resist the initial infection and to suppress viral replication. A host gene designated Cmv1 has been identified which encodes a natural killer (NK) cell receptor that confers resistance to infection. This receptor, the ligand for which is Ly49H, recognizes MCMV directly and its stimulation induces NK cell expansion and activation.(8) NK cells suppress the infection by direct lysis of infected cells and by producing cytokines to mediate T-cell responses. Counteracting the host immune system are a number of viral genes, the products of which modify the host immune response by inhibition of NK cell function, blocking of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte function, or inducing resistance to interferon or complement. T-lymphocytes, especially cytotoxic CD8+ cells, are activated by NK cell cytokines, and they play an important role in controlling the MCMV infection and in inducing the state of latency. CD4+ cells are involved to an extent in modulating the CD8+ response, but depletion of these cells does not alter the course of infection. Humoral immunity is relatively unimportant in controlling MCMV infection.Â

Latent virus in the mouse is identifiable in the salivary glands and in other tissues including lung, spleen, liver, kidney, heart, adrenal glands, and myeloid cells. The severity of reactivated infection may be related to the severity of the initial infection, that is, to the number of cells in which latent virus resides.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with karyomegaly and intranuclear viral inclusions.Â

2. Spleen: Splenitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with lymphocytolysis, karyomegaly and intranuclear viral inclusions.Â

Conference Comment:

Natural infections of cytomegalovirus are observed in primates and guinea pigs in addition to mice. Rhesus cytomegalovirus (macacine herpesvirus-3) is the most common opportunistic viral infection in rhesus macaques infected with SIV.(1) It causes multiorgan pathology, with interstitial pneumonia, encephalitis, gastroenteritis, and lymphadenitis being most common.(2) Viral infection is commonly associated with neutrophilic infiltrates, regardless of tissue, and when it occurs in conjunction with simian polyomavirus 40, mesenchymoproliferative enteropathy has been described.(9) Recently, peripheral nerve lesions such as facial neuritis have been identified in macaques, which are likely a bystander effect secondary to inflammation and infected macrophages.(1) In guinea pigs, lesions are largely regarded as incidental findings at necropsy and usually confined to the ductal epithelial cells of the salivary glands.(10)

The contributor details the importance of NK cells in resisting and controlling murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection in mice. Of special interest is the ability of NK cells to clonally expand upon activation of the Ly49H receptor. This stimulated NK cell population persists for months following the resolution of infection, and when the animal is re-introduced to MCMV, a secondary expansion occurs, conferring resistance to re-infection, effectively demonstrating the generation of memory within this cell population.(6) This a well-known feature of T cells in the adaptive immune response, but NK cells are typically described as an important component of the innate immune response, especially concerning virus-infected and neoplastic cells. NK cell regulation occurs through cytokine expression (IL-2 and IL-15 stimulate proliferation, IL-12 activates killing) and inhibitory receptors which recognize the class I MHC molecules expressed by all healthy cells. Viral infection or neoplastic transformation often reduces class I MHC expression in a cell, thereby activating NK cells to destroy it. Activated NK cells, which all express CD16 and CD56, also secrete IFN-γ which activates macrophages.(7) Interestingly, C57BL/6 (B6) mice are readily recognized as having resistance to MCMV due to Ly49H expression, and its infection in this case indicates a possible deficiency in one of the several factors critical for generation of memory NK cells in MCMV infection: IL-12, microRNA-155, and DNAM-1.(6) Conference participants discussed their top differentials for necrotizing hepatitis in mice. Other viral infections include: mouse adenovirus-1 (intranuclear inclusions), mouse hepatitis virus (viral syncytia), mousepox (intracytoplasmic inclusions), and mammalian orthoreovirus (only in infant mice). Bacterial causes include Helicobacter spp., Clostridium piliforme, Salmonella spp., Proteus mirabilis, and Listeria monocytogenes as demonstrated in WSC 14-15 Conference 6.Â

References:

1. Assaf BT, Knight HL, Miller AD. Rhesus cytomegalovirus (Macacine herpesvirus 3)-associated facial neuritis in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol. 2015;52(1):217-223.

2. Baskin GB. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection in immunodeficient rhesus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1987;129(2):345-352.

3. Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010:20(4):202-213.

4. Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayward GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AC, et al. The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 2009:154(1):171-177.

5. Fox JG. The Mouse in Biomedical Research. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2007.

6. Kamimura Y, Lanier LL. Homestatic control of memory cell progenitors in the natural killer cell lineage. Cell Rep. 2015;10(2):280-291.

7. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Diseases of the immune system. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:192.

8. Lee SH, Kim KS, Fodil-Cornu N, Vidal SM, Biron CA. Activating receptors promote NK cell expansion for maintenance, IL-10 production, and CD8 T cell regulation during viral infection. J Exp Med. 2009:206(10):2235-2251.

9. Macri SC, Knight HL, Miller AD. Mesenchymoproliferative enteropathy associated with dual simian polyomavirus and rhesus cytomegalovirus infection in a simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol. 2012;50(4):715-721.

10. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:222.