WSC 2023-2024, Conference 20, Case 4

Signalment:

3-week-old female suckling domestic piglet (Sus scrofa domesticus)History:

The farm noticed increased morbidity and mortality of approximately 20-30% during the last three weeks. The piglets showed clinical signs of diarrhea, fever, lameness, tremor, and anemia. This animal was euthanized for diagnostic proposes shortly before necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

The animal was in poor nutritional condition. There was a small amount of milk in the stomach. The contents of all intestinal segments were yellow and watery. A high amount of turbid synovial fluid was found in all examined joints. The meninges were diffusely cloudy.

Laboratory Results:

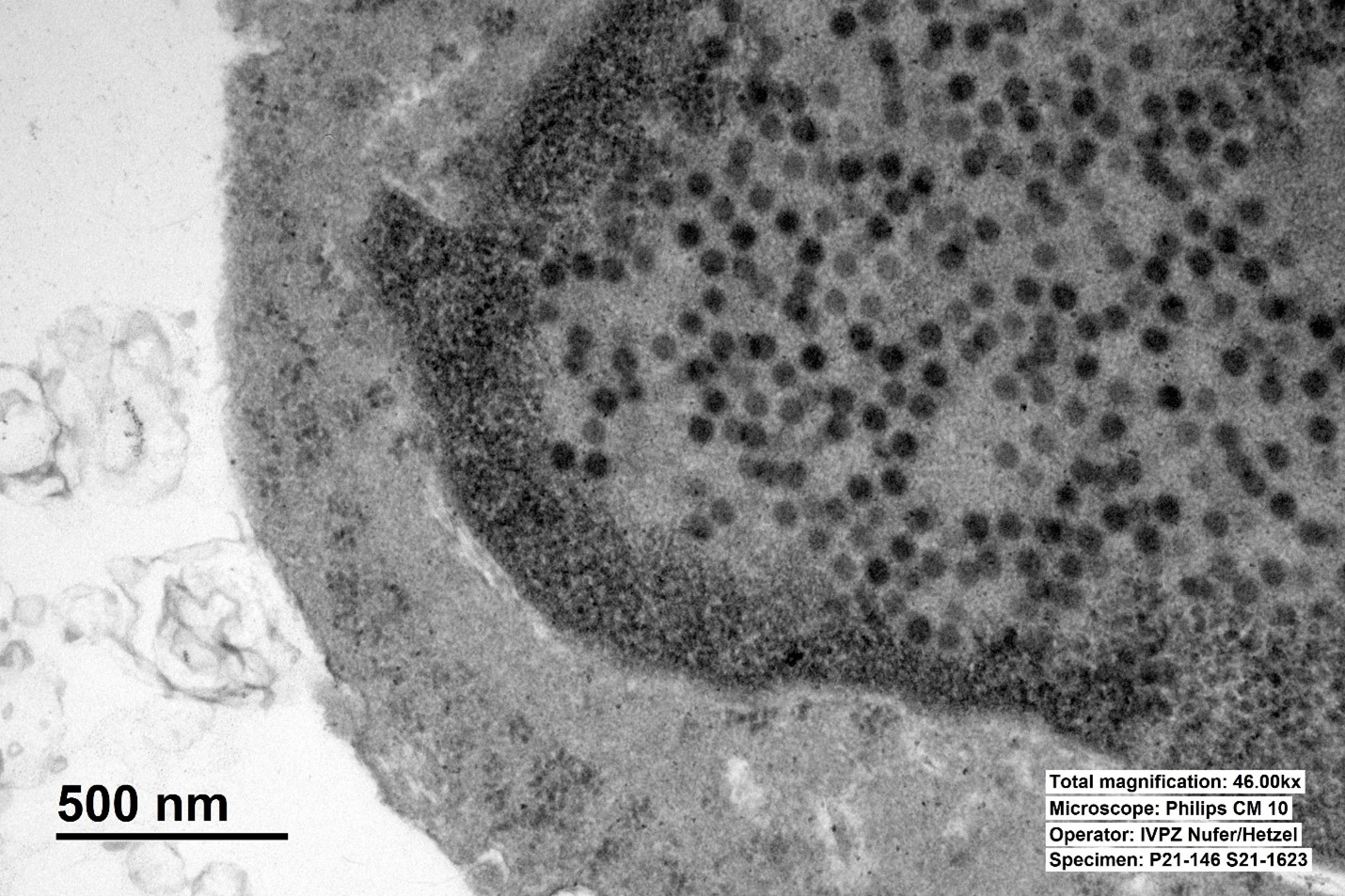

Adenoviral particles were detected by transmission electron microscopic examination of the ileal mucosa.

In the bacteriological examination of an elbow joint (synovia) and of the brain meninges a small amount of Streptococcus suis was isolated. PCR serotyping identified S. suis Serotype 1.

No parasites were identified on fecal flotation.

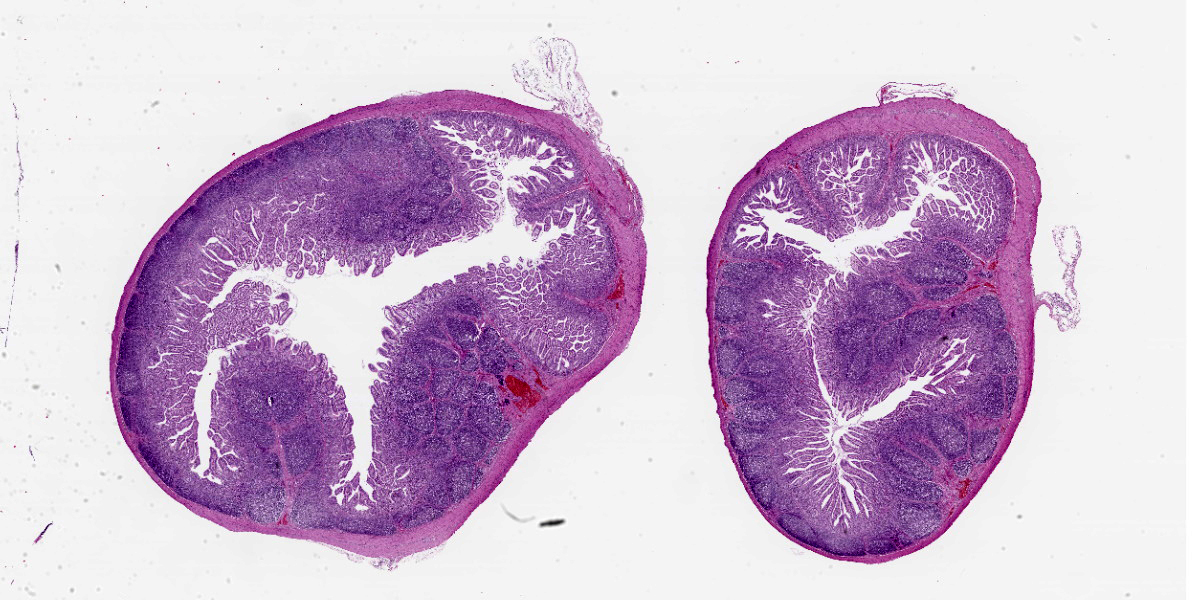

Microscopic Description:

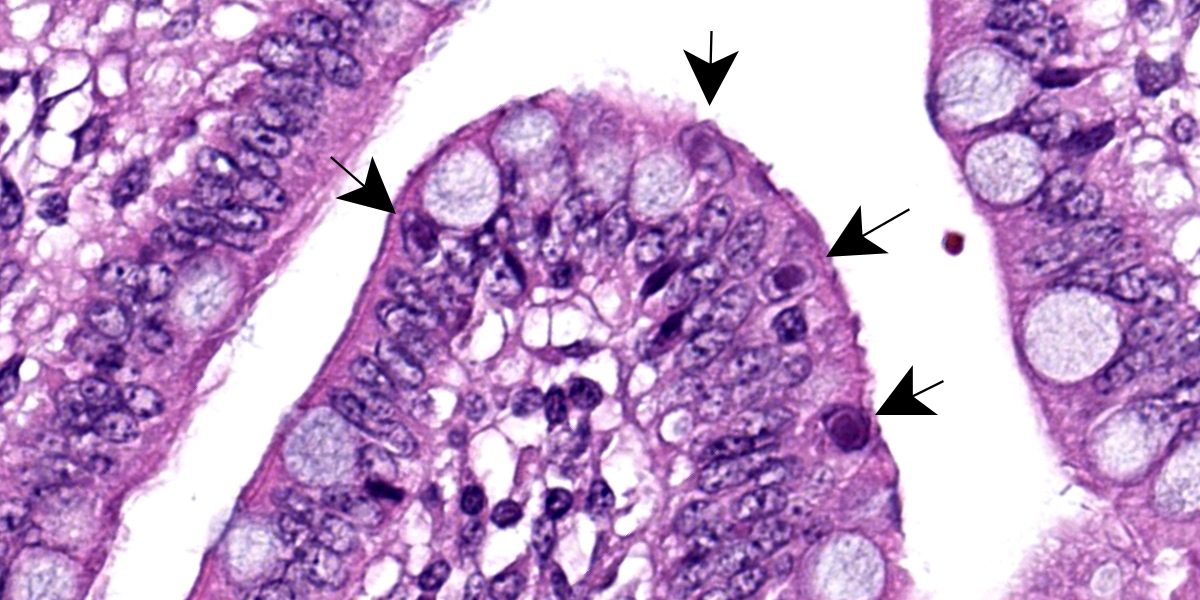

Multifocally, ileal villi are mildly to moderately fused and blunted with maintenance of normal enterocyte architecture. Enterocytes occasionally contain a single intranuclear inclusion body that leads to margination of the chromatin. These inclusion bodies are amphophilic, round to oval shaped, and 5-15 µm in diameter. In the lamina propria, a mild diffuse infiltration with lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and granular lymphocytes is present. The vessels show an increased number of erythrocytes (congestion).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mild, subacute, diffuse, lymphoplasmatic and eosinophilic enteritis (ileitis) and mild, multifocal, atrophic enteritis with villus fusion and intranuclear viral inclusion bodies (Adenovirus).

Contributor’s Comment:

Adenoviruses are non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with icosahedral symmetry. Adenovirus infections occur in a wide variety of animals inducing clinical signs ranging from subclinical to enteric or respiratory. Three species of Porcine adenoviruses (PAdVs), Porcine mastadenovirus A, Porcine mastadenovirus B, and Porcine mastadenovirus C, and five serotypes have been identified by virus neutralization assays.1,3,7 Adenoviruses are considered host-specific and the pig is the only known species that is susceptible to PAdVs.1

Watery to pasty diarrhea, dehydration, and decreased weight gain are the most commonly observed clinical signs in pigs.1 Cases of diarrhea caused by PAdVs are mostly seen in suckling pigs (1–4 weeks of age), but weaned and fattening pigs can also be affected.1 Furthermore, PAdVs have been isolated from pigs with respiratory signs, encephalitis, nephritis, and abortions; they have also been isolated from animals without evident clinical history.1,3-5 Transmission occurs mostly via the fecal-oral route or possibly by aerosol exposure. Mechanical vectors (tools, boots, vehicles, etc.) might have a possible role considering the high stability of the virus in the environment.1

Similar to this case, typical histological lesions include villous fusion, blunting, and shortening with intranuclear basophilic inclusion bodies in enterocytes of the distal jejunum and ileum.1,8 To confirm an infection with PAdVs, the virus can be detected by electron microscopy, cytology from mucosal smears, or by the detection of viral antigens in tissues by immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry.1,6 In general, PAdVs mostly lead to subclinical infections and are not known to have public health significance. Adenoviruses should nevertheless be considered as a differential diagnosis for gastrointestinal and possibly respiratory diseases in pigs.1

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Veterinary Pathology Zurich

www.vetpathology.uzh.ch

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Enteritis, lymphoplasmacytic, diffuse, mild, with few epithelial intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment:

Adenoviruses, so named due to their discovery in cultures of human adenoids, are notable histologically for their large, often basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies. These inclusions represent newly assembled virions that form crystalline aggregates within the nucleus.9 As flashy as these inclusions may be, as the contributor notes, adenoviral infection in pigs is typically asymptomatic, with the main presenting signs being yellow, watery diarrhea of three to four days’ duration in 1-4 week old piglets.2

Once ingested, porcine adenovirus undergoes intranuclear replication, primarily in the enterocytes and lymphoid tissue located in the distal jejunum and ileum.2 Viral antigen may be found 24 hours after infection and for up to 45 days post-infection, and infected enterocytes may be destroyed or may lose their villi during the acute phase of infection.2 Interestingly, virus has been found in the tonsils after infection of enterocytes, raising the possibility of clinically silent viremia with certain isolates.2 Porcine adenovirus has also rarely been associated with nephritis, raising the possibility of urinary-oral and urinary-nasal transmission.2

Gross lesions in cases of adenovirus-induced diarrhea include thinning of the wall of the distal small intestine, enlargement of the mesenteric lymph nodes, and the presence of yellow, watery contents in the small and large intestines.2 In additional to the histologic features described by the contributor, the lamina propria is often infiltrated by histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes, as illustrated by this case. In cases of porcine adenovirus nephritis, the renal interstitium contains multifocal accumulations of lymphocytes and plasma cells, and renal tubules contain sloughed, necrotic tubular epithelial cells, some of which may contain characteristic intranuclear inclusion bodies.9

Aside from the eye-catching inclusion bodies, histologic lesions in the examined section were subtle, leaving participants rooting around for descriptive points. Conference participants discussed the length of the villi and, while the contributor described fused and blunted villi, these changes were not appreciated in the examined section. Participants also noted multifocal areas where crypt and villar epithelium appeared hyperplastic and piled up, though most felt these apparent lesions were simply function of cut. Similarly, the occasional lymphocytolysis observed in Peyer’s patches were thought to be within normal limits as some lymphocytolysis is expected during normal lymphocyte turnover.

Discussion turned to the quantity and character of the inflammatory cells, which left some participants unimpressed; however, the majority felt that the number of lymphocytes and plasma cells was mildly elevated and likely responsive to the obvious viral infection being telegraphed by the inclusion bodies.

The moderator noted that, while diarrhea can be experimentally induced by PAdVs, current veterinary literature is divided on whether these viruses cause porcine diarrhea in natural infections. While direct causation is not definitively established, PAdVs should be on differential lists of porcine diarrhea, particularly in the absence of other common etiologic agents, such as rotavirus or coronavirus, which can cause subtle histologic lesions similar to the examined case while causing significant to profound clinical diarrhea.

References:

- Benfield DA, Hesse RA. Adenoviruses. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, et al., eds. Diseases of Swine. 11th ed. Wiley & Sons;2019:438-441.

- Center for Food Security and Public Health. Porcine Adenovirus. Iowa State University;2015. Available at: cfsph.ia state.edu/pdf/which-factsheet-porcine-adenovirus.

- Clarke MC, Sharpe HBA, Debryshire JB. Some characteristics of three porcine adenoviruses. Agricultural Research Council, Institute for Research on Animal Diseases, Berkshire England;1967:91-97.

- Ducatelle R, Coussement W, Hoorens J. Sequential pathological study of experimental porcine adenovirus enteritis. Vet Pathol. 1982;19:179-182.

- Haig DA, Clarke MC. Isolation of an adenovirus from a pig. J Comp Pathol. 1964;74:81-84.

- Nietfeld JC, Leslie-Steen P. Interstitial nephritis in pigs with adenovirus infection. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1993;5:269-273.