WSC 2022-2023

Conference 21

Case 2

Signalment:

1-year-old, male, Domestic Shorthair Cat (Felis catus)

History:

A 1-year-old indoor male Domestic Shorthair cat was found deceased with no premonitory signs. The history indicated a prolapsed rectum had been surgically repaired in the past.

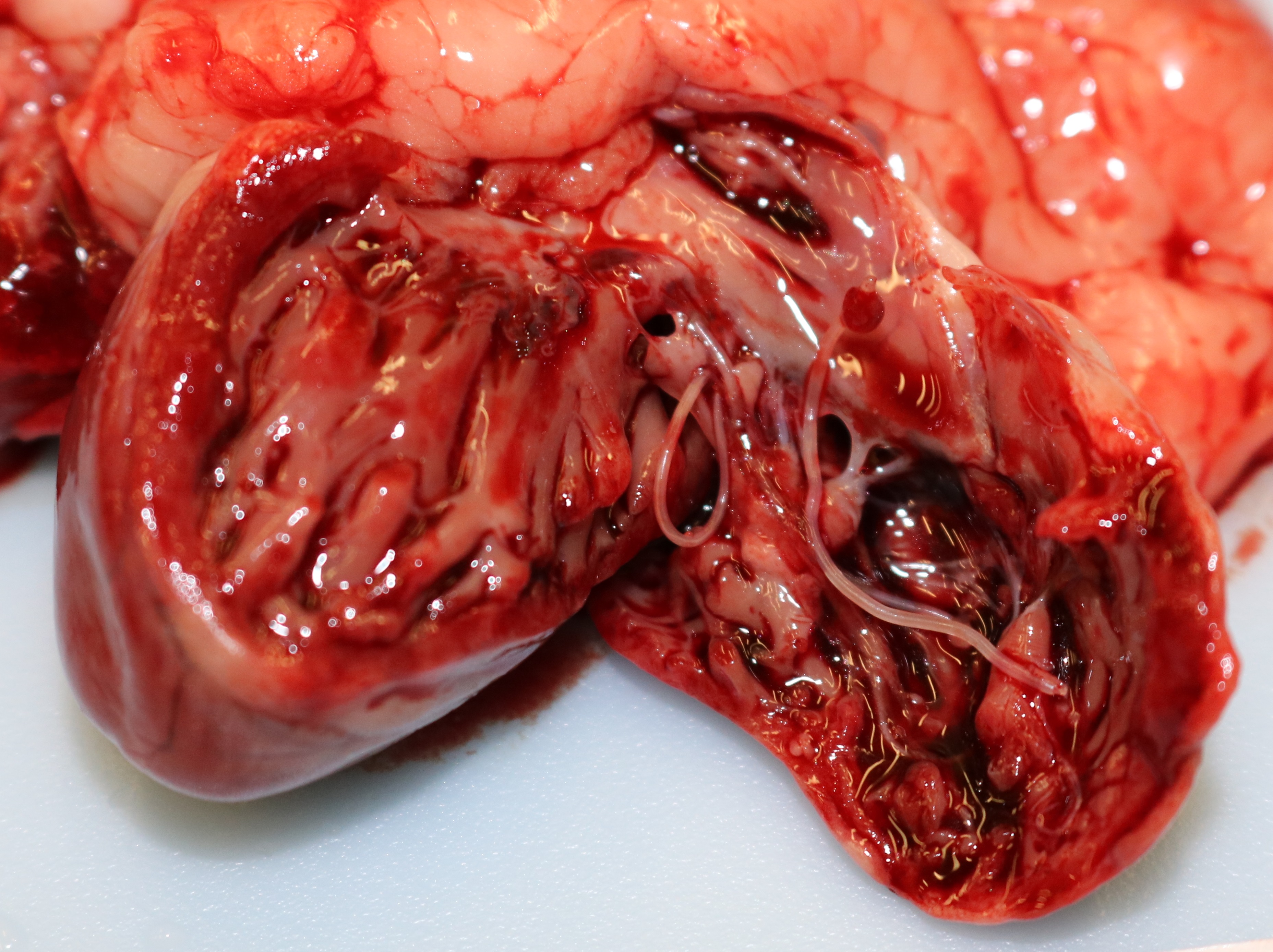

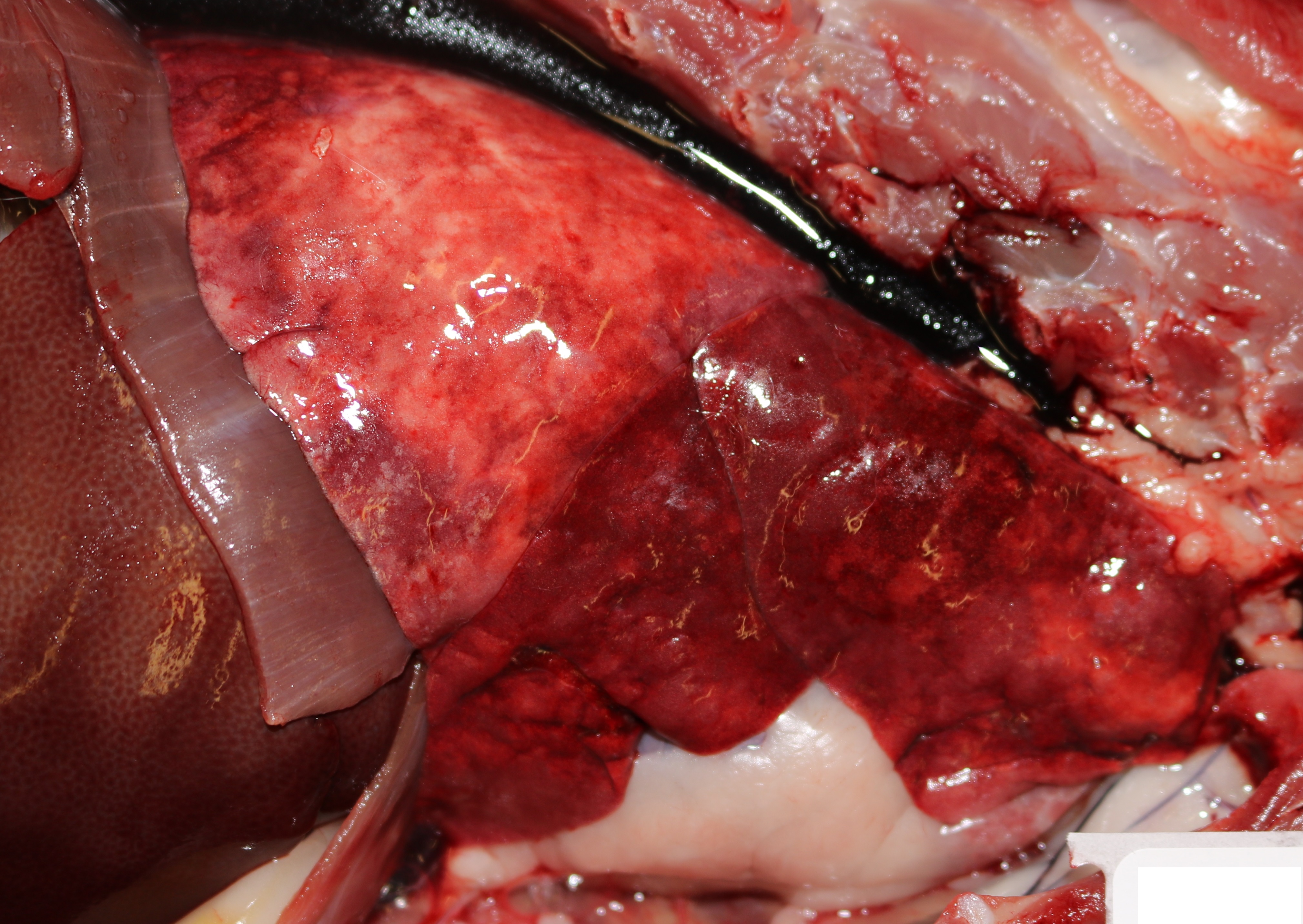

Gross Pathology:

Grossly, the lungs were diffusely edematous, mildly consolidated, and mottled dark red to red with petechial hemorrhages. The distal trachea and bronchi contained moderate amounts of yellow mucus and foamy fluid. There were two 4-5 cm long white worms in the right cardiac ventricle, located at the tricuspid valve. An oval 1 cm area of intimal hemorrhage was present in the base of the pulmonary artery. The heart was within normal limits for size and shape.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

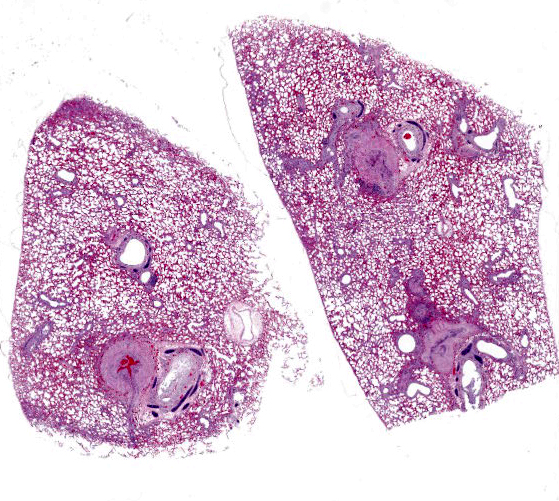

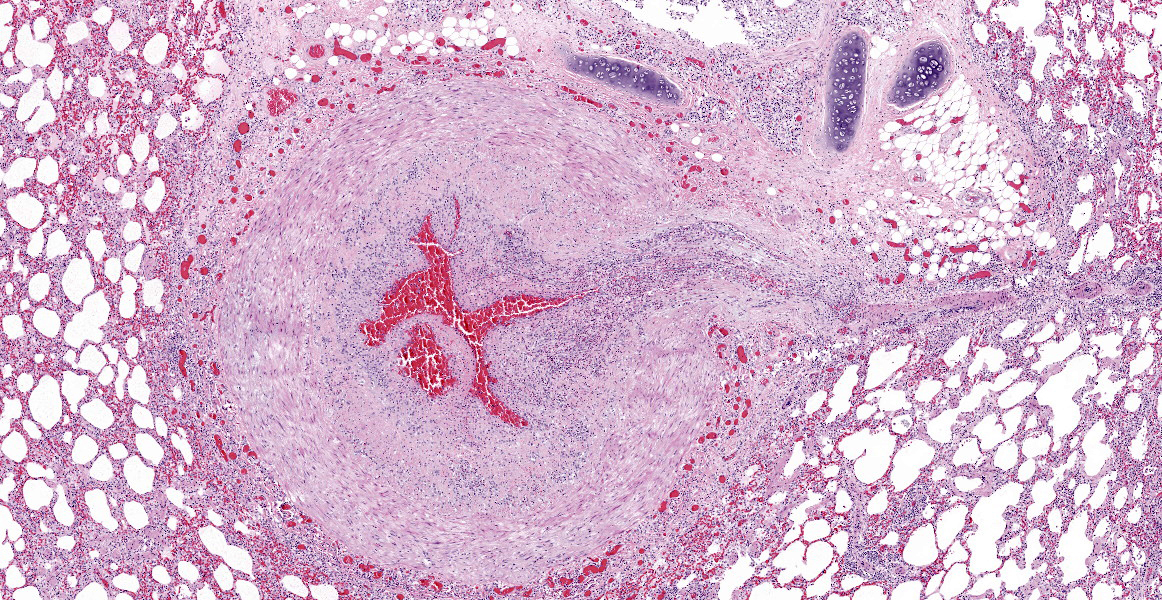

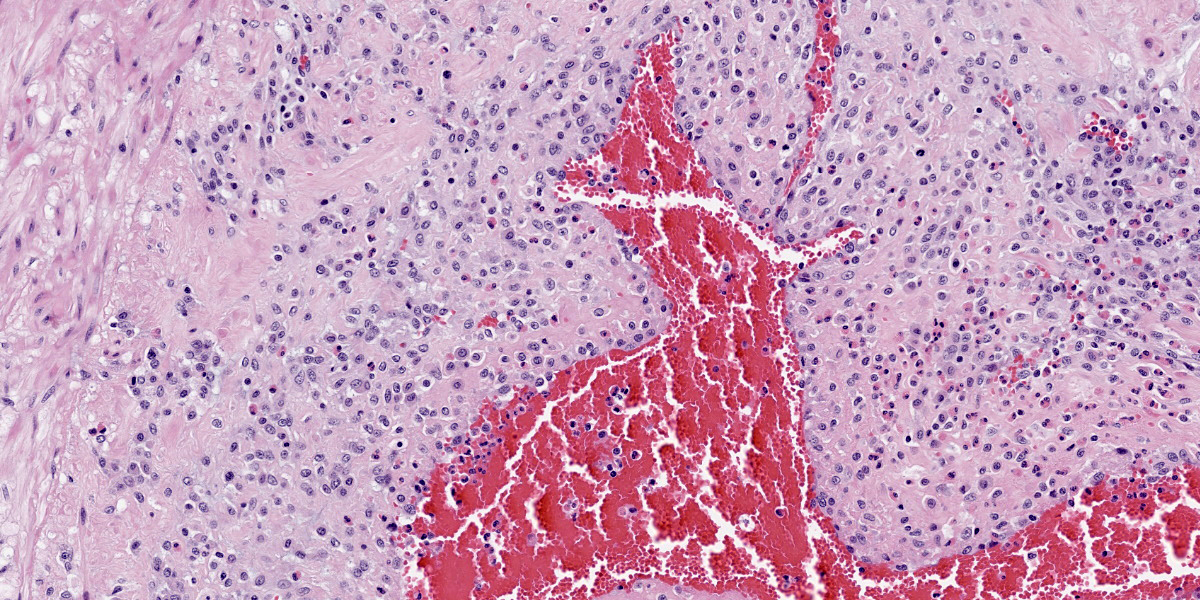

Microscopic Description:

Multifocally, the tunica intima of the small and medium-sized pulmonary arteries are markedly thickened and have villous-like proliferations that protrude into the lumens, partially or completely occluding the arteries. The intimal proliferations are often lined by hypertrophied endothelial cells and consist of fibrous connective tissue with hyperplastic fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Moderate to marked infiltration by eosinophils, macrophages, fewer lymphocytes, and plasma cells are present in the affected tunica intima, occasionally associated with minimal hemorrhage. In some arteries, the lumen is completely obliterated by endothelial proliferation, with a few small blood vessels lined by hypertrophied endothelial cells. Often, the internal elastic lamina is effaced and obscured by the intimal proliferation and inflammation. Most of the pulmonary arteries and arterioles, with or without intimal changes, are narrowed and have moderate hypertrophy of the tunica media. The alveolar septa adjacent to the affected arteries are moderately thickened by infiltration by eosinophils, macrophages, and fewer lymphocytes. Occasionally, the alveoli contained increased numbers of foamy macrophages, fewer eosinophils, hemorrhage, rare edema, and minimal amounts of fibrin. There are multiple granular, linear, or round concentric basophilic mineralized deposits in the pulmonary capillaries, bronchiolar smooth muscles, and arterial media. Round concentric deposits, some resembling corpora amylacea, are 15-20 microns in diameter and often located in the connective tissue around arteries and bronchi. The pulmonary capillaries are diffusely congested.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lung, arteries: (1) Endarteritis, proliferative and eosinophilic, chronic, multifocal, moderate to marked, with occasional luminal occlusions and re-canalizations; (2) Medial hypertrophy, diffuse, mild to moderate.

Lung: (1) Interstitial pneumonia, eosinophilic and histiocytic, multifocal, mild; (2) Mineralization, multifocal, moderate

Contributor’s Comment:

Dirofilaria immitis commonly causes clinical diseases in dogs, but can infect other mammals including cats, wild felids, wild canids, and rarely humans.15 Typical histological lesions in lungs in both dogs and cats caused by D. immitis are villous proliferation of the arterial intima with medial hypertrophy and eosinophilic infiltrates.12,15

Mosquitoes play the main role in the heartworm lifecycle. The first, second, and early third stage larvae of D. immitis are obligate parasites of mosquitoes of the genera Aedes, Culex or Anopheles. In mosquitoes, larvae develop to the infective stage in the malpigphian tubules and then migrate to the proboscus. When mosquitoes feed on hosts, the infective third stage larvae deposit on the skin and enter through the bite wound. The third stage larvae molt to the fourth stage and become immature adults in the connective tissue. Finally, immature adults enter the veins and migrate to the pulmonary arteries, 70-90 days postinfection. The immature adults mature in 3 months to adults, after which time female worms produce microfilariae. The average pre-patent period is 6-8 months for D. immitis.10,11,15

Dogs are the natural definitive host of D. immitis, and canine dirofilariasis occurs when heartworms become adults and produce microfilariae. In dogs, the most common clinical presentation is a chronic congestive right cardiac failure with more than 30 adult worms, and it is usually seen in dogs older than 5 years with continuous or multiple infections. Mechanical irritation by adult worms and microfilariae can cause pulmonary arterial sclerosis and hypertension, leading to chronic heart failure. Also, large numbers of adult D. immitis (usually more than 100) infecting the right atrium and vena cava can result in acute venous obstruction and shock, known as vena cava syndrome.15

The prevalence and pathogenesis of feline dirofilariasis is somewhat different from dogs.10,11 The distribution of feline dirofilariasis parallels that of dogs, but the overall prevalence is between 5-10 % of that in dogs in any given area.16 Mosquitos feeding preferences and the poor suitability of cats as definitive hosts may be reasons for this low prevalence.10 Since cats are atypical hosts for D. immitis, the majority of worms are cleared in the immature adult stage, and there are typically only 2-4 adult worms infect the heart. Due to low numbers of adult worms and poor suitability, cats tend to be amicrofilaremic or have only a short (2-3 months) microfilaremic period.6,10,11 Vena cava syndrome caused by a large burden of D. immitis infection has been described rarely in cats.12 Similar to dogs, chronic heartworm disease with adult worms occurs in cats, but congestive right cardiac failure or pulmonary hypertension are rare.17

Chronic feline dirofilariasis caused by adult worm infection can cause death,10,11 as seen in this case. Cats may be asymptomatic or show chronic respiratory signs such as coughing or intermittent dyspnea during the infection.1,6 Vomiting is also a relatively common finding, reported in about half of the cases with unknown pathogenesis 1. Unlike most cases of canine dirofilariasis, acute respiratory distress and sudden death with adult heartworms in cats are attributed to embolization of dead worms causing pulmonary arterial infarction and circulatory collapse.6,10,11 Adult heartworms are believed to secrete a product that suppresses the activity of the pulmonary intravascular macrophage (PIM), the main component of the reticuloendothelial system in cats; PIM are not present in normal dogs.8 Decreased PIM activity results in an anti-inflammatory reaction and minimizes the clinical signs of cats having adult worms, but the death of adult worms triggers an intense inflammatory reaction.8,10

Additionally, there is a condition known as heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD) in cats, that is caused by the death of larvae in caudal pulmonary arteries before they migrate into the heart.7,10,15, Clinical respiratory signs associated with HARD are similar to chronic feline dirofilariasis, but occur around 3-6 months post-infection without any adult worms.7,10 The strong inflammatory response induced by larval death is also hypothesized to be due to the activity of PIM only seen in cats.8,10

Histological presentation of chronic feline dirofilariasis and HARD is similar, but HARD has less severe lesions.3,17 The fibromuscular intimal proliferation has been considered a reaction to heartworms, but a response to intracellular bacteria Wolbachia harbored by D. immitis may be involved.10,12,14 Arterial medial hypertrophy is another common finding in both cats and dogs infected with D. immitis.12,15 In cats, this change can be spontaneous, and also can be caused by other parasites such as Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Toxocara cati.12,14 However, a recent experimental study revealed a strong association of smooth muscle hypertrophy of arteries, bronchi, and bronchioles in cats infected with D. immitis.7 Without any adult heartworms, pulmonary proliferative and/or eosinophilic endarteritis is suggestive for larval D. immitis infection. As with hypertrophy of the arterial tunica media, migration of other larval worms (including Toxocara spp), is known to cause eosinophilic endarteritis in feline lungs.14

Aberrant migration of D. immitis occurs with greater frequency in cats than in dogs.9,14 Aberrant migration of larvae to body cavities, eyes, and central nervous system are more common in cats, inducing an inflammatory response at the site of migration.9,10 Recently, aberrant migration of heartworms to the femoral artery causing hind limb paresis was described in a cat.13 Migrating D. immitis should be considered for any nematodes found anywhere in cats.

There was conversation about concentric mineral deposits in the pulmonary connective tissues in this cat as to whether they were dead larvae or spontaneous mineralization. Some of deposits had fragmented or concentric structures but were not associated with any inflammation, and there were no histologically identifiable larvae. It is known that dead D. immitis tend to induce strong inflammation.9 No other cause for arterial mineralization was identified on anatomic examination, and antemortem bloodwork was not available. The cause of this widespread mineralization was not identified.

Contributing Institution:

Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory

http://cvmdl.uconn.edu/

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung, arteries, and arterioles: Endarteritis, proliferative and eosinophilic, diffuse, severe, with marked smooth muscle hypertrophy.

JPC Comment:

The fundamental histologic finding in this case is neointimal proliferation of pulmonary arteries. During the conference, the moderator and conference participants discussed presence of visible small caliber blood vessels in the expanded region of the tunica inwhich represents either neovascularization or hypertrophy of existing, penetrating vasa vasorum. Indeed, immunohistochemical and special stains were helpful to evaluate the character of the intimal proliferation: negative reactivity to smooth muscle actin and abundant factor 8 immunoreactivity confirmed that the majority of the proliferation is from small caliber vessels. Conference participants also discussed the presence of interstitial pneumonia, but felt the changes were mild and did not warrant morphologic diagnosis. The fatal outcome of such a low parasite load in cats is enigmatic, in this case there were no filaria, nor evidence of emboli (in sections examined)

The contributor provides a good summary of the histologic lesions of the pulmonary vasculature in cats, as well as the parasite life cycle, clinical signs, and pathogenesis of this disease. Heartworm infection may also lead to membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis due to deposition of antigen-antibody complexes, or to glomerular damage fraying and thickening glomerular basement membrane, both of which lead to proteinuria.5,15

Dirofilaria can cause similar lesions in dogs. Dogs also can harbor Angiostrongylus vasorum, which can cause proliferative endarteritis, intimal proliferation, and medial hypertrophy in the lung.4 This metastrongyle differs from D. immitis in both life cycle and pathogenesis. The intermediate host of A. vasorum is a mollusk (snail or slug), which is ingested by a dog. Larvae migrate through the lymph nodes, where they molt, and adults reside in the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle.2,4 Eggs pass into the pulmonary vessels, hatch, and penetrate into alveolar lumen, eventually to be coughed up, swallowed, and passed into the feces. These eggs and larvae can cause granulomatous pneumonia, occasionally forming larger granulomas containing mixed inflammatory cells, while the adult worms cause characteristic proliferative endoarteritis.4Histologically, the presence of eggs in the granulomatous inflammation and within adult female nematodes is a helpful differentiating feature between A. vasorum and D. immitis; other differences include a thin coelomyarian musculature and a large intestine in A. vasorum compared to tall coelomyarian musculature and a small intestine in D. immitis.4

References:

- Atkins CE, DeFrancesco TC, Coats JR, et al. Heartworm infection in cats: 50 cases (1985-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc.2000; 217(3):355-8.

- Bowman DD. Helminths. In: Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 11th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2021; 203.

- Browne LE, Carter TD, Levy JK, et al. Pulmonary arterial disease in cats seropositive for Dirofilaria immitisbut lacking adult heartworms in the heart and lungs. Am J Vet Res. 2005; 66(9):1544-1549.

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 586-587.

- Cianciolo RE, Mohr FC. Urinary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 418.

- Dillon R. Feline Dirofilariasis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Prac 1984; 14(6): 1185–1199.

- Dillon AR, Blagburn BL, Tillson M, et al. Heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD) induced by immature adult Dirofilaria immitis in cats. Parasit Vectors.2017; 10(suppl 2):514.

- Dillon AR, Warner AE, Brawner W, et al. Activity of pulmonary intravascular macrophages in cats and dogs with and without adult Dirofilaria immitis. Vet Parasitol.2008; 158(3):171-6.

- Donahoe JM. Experimental infection of cats with Dirofilaria immitis. J Parasitol. 1975; 61:599-605.

- Lee AC, Atkins CE. Understanding feline heartworm infection: disease, diagnosis, and treatment. Top Companion Anim Med. 2010; 25(4):224-230.

- Lister AL, Atwell RB. Feline heartworm disease: a clinical review. J FelineMed Surg. 2008; 10:137-144.

- McCracken MD, Patton S. Pulmonary arterial changes in feline dirofilariasis. Vet Pathol. 1993; 30:64-69.

- Oldach MS, Gunther-Harrington CT, Balsa IM, et al. Aberrant migration and surgical removal of a heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) from the femoral artery of a cat. J Vet Intern Med.2018; 32(2):792-796.

- Parsons JC, Bowman DD, Grieve RB. Pathological and haematological responses of cats experimentally infected with Toxocara canis larvae. Int J Parasitol. 1989; 19(5):479-488.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 83-85.

- Ryan W, Newcomb K. Prevalence of feline heartworm disease - a global review. Proceedings of the Heartworm Symposium ‘95, Auburn, Alabama. Batavia, Illinois: American Heartworm Society.

- Winter RL, Ray Dillon A, Cattley RC, et al. Effect of heartworm disease and heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD) on the right ventricle of cats. Parasit Vectors.2017; 10 (Suppl 2):492.