Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Alveoli are multifocally lined by 2-3 layers of epithelial cells (moderate hyperplasia) and occasionally contain lipid vacuoles. The interlobular septa are expanded by a moderate amount of fibrous connective tissue. In some sections moderate to severe atrophy of alveoli secondary to severe interstitial fibrosis is evident.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

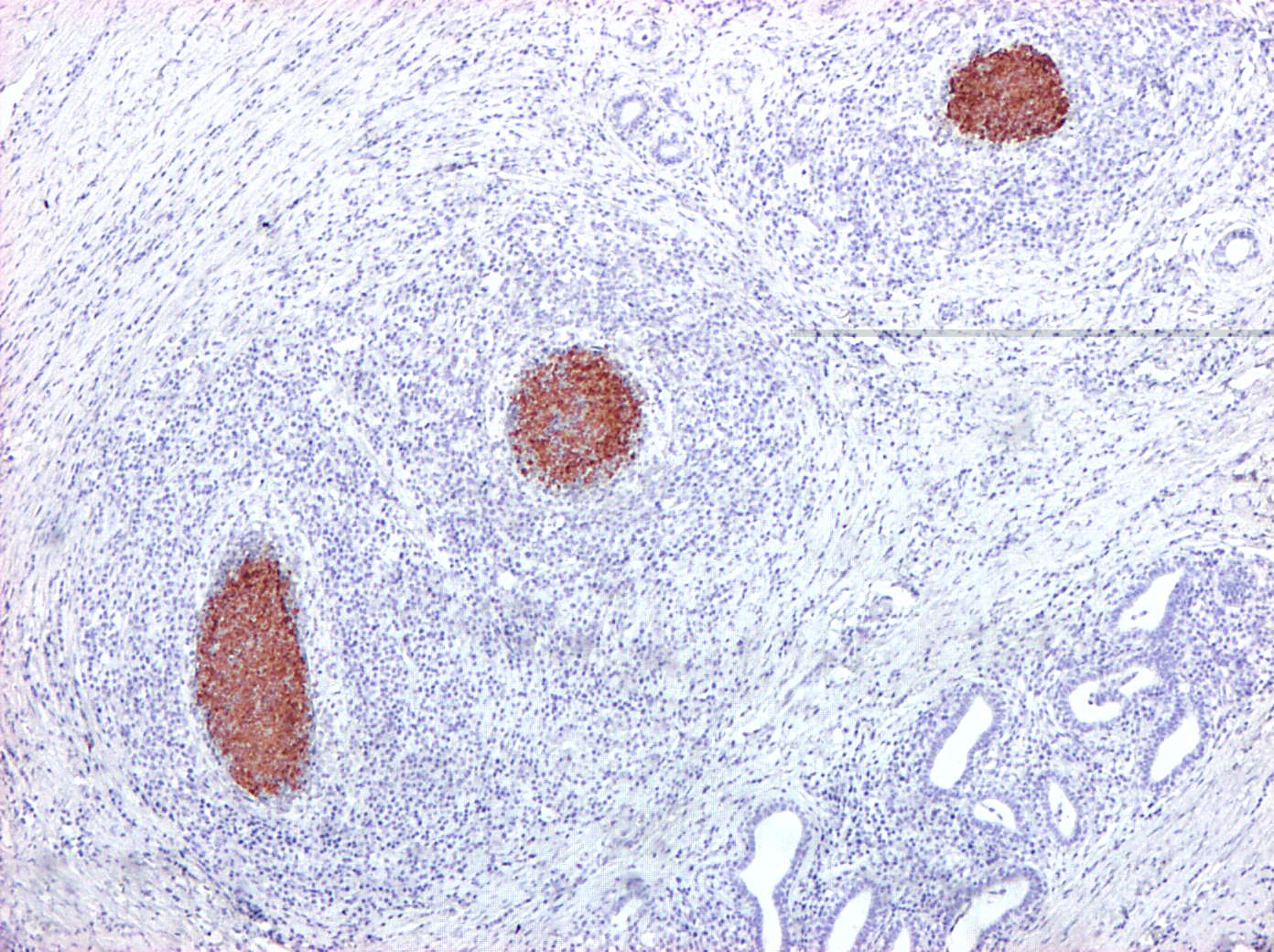

Immunohistochemically, abundant M. bovis antigen was detected in the cytoplasm of degenerate neutrophils and foamy reactive macrophages or admixed with the necrotic debris (Fig. 2 and 3). Necrosuppurative foci were surrounded by severe fibrosis with marked infiltration of degenerated neutrophils, CD3-positive T-cells, CD79α- positive B-cells, and CD68-positive histiocytes.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Besides its major role as a respiratory pathogen and as a causative organism of polyarthritis in beef cattle, M. bovis is also considered an important agent of mastitis in dairy cows. Mastitis caused by M. bovis has been estimated to cost the U.S. dairy industry over USD $100 million annually, with infection rates of up to 70% in some herds, which is even greater than the losses resulting from mycoplasmal pneumonia.(9) Over recent years, with the replacement of classical bacteriological techniques and the development of more reliable and accurate PCR and ELISA-based diagnostic tests for the identification of mycoplasmas, M. bovis is being increasingly recognized as a primary agent of mastitis also in Europe.(1) The substantial economic losses caused by M. bovis derive from the development of a chronic progressive mastitis with decreased milk production and lower milk quality. Because no efficacious antibiotics or vaccines have been approved for the treatment or prevention of M. bovis mastitis, culling is recommended for controlling the disease, even if this drastic measure of control results in considerable animal replacement costs.(10)

Epidemiological and pathogenetic mechanisms responsible for M. bovis-induced mastitis are far from being fully elucidated. Ascending and hematogenous routes of infection are both implicated in the development of disease. Fomites, such as contaminated milking equipment or solutions used for intramammary infusion, represent the most documented routes of M. bovis transmission among dairy cows. The existence of environmental sources for M. bovis and their role in transmission and clinical disease are poorly characterized, although recent investigations pointed out the role of recycled bedding sand as a potential source of M. bovis.(6) Secondary colonization of the mammary glands starting from primary foci of bronchopneumonia and polyarthritis or during septicemia has been also postulated as a likely event leading to mastitis. The contrary is also true where the mammary gland acts as a primary focus of infection followed by septicaemia and polyarthritis. Vertical transmission of M. bovis with congenital mammary gland infection in prepubertal heifers has been also hypothesized in a recent investigation. In dairy herds, direct galactogenic transmission of M. bovis infection from cows with mastitis represents one of the main causes of bronchopneumonia, otitis media and polyarthritis in suckling calves.(4,14)

M. bovis infection of the mammary gland elicits a persistent inflammatory response characterized by the upregulation of several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, complement activation, massive local recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils and drastic increase in vascular permeability. Despite the sustained inflammation mounted by the host in response to M. bovis, several lines of evidence suggest that this reaction is not sufficient to eradicate the pathogen from the mammary gland, and infection usually persists over multiple lactations.(2,7) A similar situation has been also observed in the context of respiratory infections where the ability of M. bovis to establish persistent infections characterized by chronic progressive bronchopneumonic lesions may result from an inadequate and ineffective Th-2-polarized immune response.(13)

Although not pathognomonic for M. bovis mastitis, the combination of the following clinical features in lactating cows should prompt the suspicion of mycoplasmal infection:

- drastic rise in bulk and individual milk somatic cell counts;

- sudden onset of agalactia, with firm swollen and painless quarters;

- rapid separation of the milk drawn from affected quarters in a floccular precipitate and a watery supernatant;

- rapid spread of the infection from quarter to quarter;

- rapid spread of the infection from cow to cow within the affected herds;

- unresponsiveness to antibiotic therapy;

- decreased milk production with marked atrophy of affected quarters in clinically recovered cows.

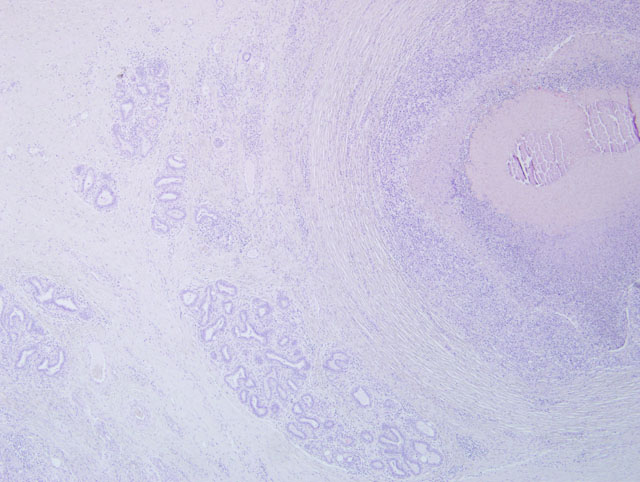

Based on the few and inconsistent data reported in the current literature, the pathology of M. bovis mastitis generally consists of an early phase dominated by massive infiltration and/or exudation of granulocytes (both neutrophils and eosinophils) in the edematous lobular interstitium, in the wall of cistern and within the acinoductal luminal compartment. The acute phase is soon followed by chronic progressive changes mainly characterized by proliferation of the affected ductuloalveolar epithelium and gradual interstitial fibrosis accompanied by infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells. Epithelial erosion/ulceration in the larger ducts and cisterns may lead to the formation of polypoid proliferations of granulation tissue protruding into and occluding the luminal compartment. The chronic phase progresses to an end stage condition where fibrosis and fibroplasia prevail on the acinoductal epithelial hyperplasia with intense atrophy and scarring of the affected parenchyma.

The few morphological studies reported so far in the literature appear largely inadequate to address the entire spectrum of pathological manifestations associated with M. bovis infection of the mammary gland. The unusual case of M. bovis mastitis provided best illustrates this concept. In contrast to the pathological features previously described for M. bovis mastitis, the lesional picture in this case is characterized by severe chronic necrosuppurative and fibrosing galactophoritis consisting of segmental ectasia of affected mammary ducts with collection of necrotic debris and degenerated neutrophils, formation of multinodular coalescing abscesses/pyogranulomas and intranecrotic foci of dystrophic mineralization. Interestingly, foci of necrosuppurative galactophoritis described share many pathological features with the characteristic M. bovis-associated bronchocentric lesions frequently observed in the lungs of beef cattle. These peculiar inflammatory changes possibly reflect a common pathogenesis for lesions originating both from bronchi/bronchioli and mammary ducts.

Gross and microscopic findings similar to those described in our case could be also elicited by other common causes of bovine galactophoritis, including Mycobacterium bovis, Nocardia asteroides, Arcanobacterium pyogenes, Prototheca zopfii, Cryptococcus neoformans. However, as confirmed by bacteriological examination, Mycoplasma bovis represented the sole bacterial pathogen implicated in our case. Furthermore, specific histochemical stains (Ziehl- Neelsen, PAS and Gram stains) were also applied to rule out other possible agents of bovine galactophoritis. Other less frequent causes of mycoplasmal mastitis in dairy cows include Mycoplasma californicum, Mycoplasma bovigenitalium and Mycoplasma canadense.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Bacterial pathogens of the mammary gland can be grouped by any one of a variety of criteria. McGavin and Zacharys Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease suggests dividing the organisms into two groups based on the source of infection to other cows. First are those in which the mammary gland itself serves as the primary source of infection, such as S. aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Mycoplasma species, and cow-to-cow transmission occurs. Second are the coliform organisms, which are acquired from the environment; infection occurs through teat contact with contaminated material or equipment. Finally, Streptococcus uberis and Streptococcus dysgalactiae form an overlapping group in which the mammary gland and environmental contamination serve as important sources of infection. This type of epidemiologic classification system provides valuable information for the producer and veterinarian regarding disease prevention and treatment.(3)

From a pathologic and pathogenesis perspective, categorizing bacterial mastitis according to the type of lesion produced is helpful in determining an underlying etiology. Gram-negative bacilli produce such lesions as vasculitis, necrosis, hemorrhage and edema, leading to endotoxemia. Gram-positive bacteria typically result in acute necrotizing mastitis or chronic suppurative mastitis. With acute necrotizing mastitis, Gram-positive bacteria, such as S. aureus, secrete bacterial products which elicit a massive neutrophilic response that contributes to extensive necrosis which progresses to gangrenous mastitis. In contrast, in chronic suppurative mastitis the pus-forming Gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and Arcanobacterium pyogenes, invoke a neutrophilic response resulting in suppuration and fibrosis, which is often centered on lactiferous ducts and sinuses; Mycoplasma bovis elicits a similar histologic lesion .(3)

Because many conference attendees considered tuberculous mycobacteria high on the differential diagnosis, a brief outline of the pathologic features of bovine mycobacterial mastitis is provided in the chart below:(11)

| Portion(s) affected | Gross appearance | Histologic appearance | Spread | |

| Disseminated miliary form | Interacinar areas |

|

|

remain localized in affected lubule(s) |

| Chronic organ form | Entire lobule Intra- and inter- lobular ducts |

|

|

Intramammary spread cia ducts; no lymph node involvement |

| Caseous tuberulous form | Entire gland |

|

|

Readily spreads to unaffected areas; no lymph node involvement |

References:

2. Byrne W, Markey B, McCormack R, Egan J, Ball H, Sachse K. Persistence of Mycoplasma bovis infection in the mammary glands of lactating cows inoculated experimentally. Vet Rec. 2005;156:767-771.

3. Foster RA. Female reproductive system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2007:1308-1314.

4. Fox LK, Muller FJ, Wedam ML, Schneider CS, Biddle MK. Clinical Mycoplasma bovis mastitis in prepubertal heifers on 2 dairy herds. Can Vet J. 2008;49:1110-1112.

5. Houlihan MG, Veenstra B, Christian MK, Nicholas R, Ayling R. Mastitis and arthritis in two dairy herds caused by Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Rec. 2007;160:126-127.

6. Justice-Allen A, Trujillo J, Corbett R, Harding R, Goodell G, Wilson D. Survival and replication of Mycoplasma species in recycled bedding sand and association with mastitis on dairy farms in Utah. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:192-202.

7. Kauf AC, Rosenbusch RF, Paape MJ, Bannerman DD. Innate immune response to intramammary Mycoplasma bovis infection. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:3336-3348.

8. Krysak DE. Chronic pneumonia and polyarthritis syndrome in a feedlot calf. Can Vet J. 2006;47:1019-1020, 1022.

9. Nicholas R, Ayling R, McAuliffe L. Mycoplasma mastitis. Vet Rec. 2007;160:382-383.

10.Nicholas RA, Ayling RD. Mycoplasma bovis: disease, diagnosis, and control. Res Vet Sci. 2003;74:105-112.

11.Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed., vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2007:558-560.

12.van der Burgt G, Main W, Ayling R. Bovine mastitis caused by Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Rec. 2008;163:666.

13.Vanden Bush TJ, Rosenbusch RF. Characterization of the immune response to Mycoplasma bovis lung infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;94:23-33.

14.Walz PH, Mullaney TP, Render JA, Walker RD, Mosser T, Baker JC. Otitis media in preweaned Holstein dairy calves in Michigan due to Mycoplasma bovis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1997;9:250-254.