CASE 4: Case 2 (4101228-00)

Signalment: Bovine, 4-week-old intact male Friesian calf (Bos taurus)

History:

The 4-week-old Friesian bull calf was one of a mob of 50 calves bought into a calf-rearing facility, from an unknown dam and sire. The calf presented with a swollen scrotum with palpable masses and marked abdominal distension. The calf was in fair body condition, with a normal demeanor and appetite, and no evidence of weakness. Abdominocentesis revealed a serosanguinous peritoneal effusion. The fluid was not submitted for analysis and euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

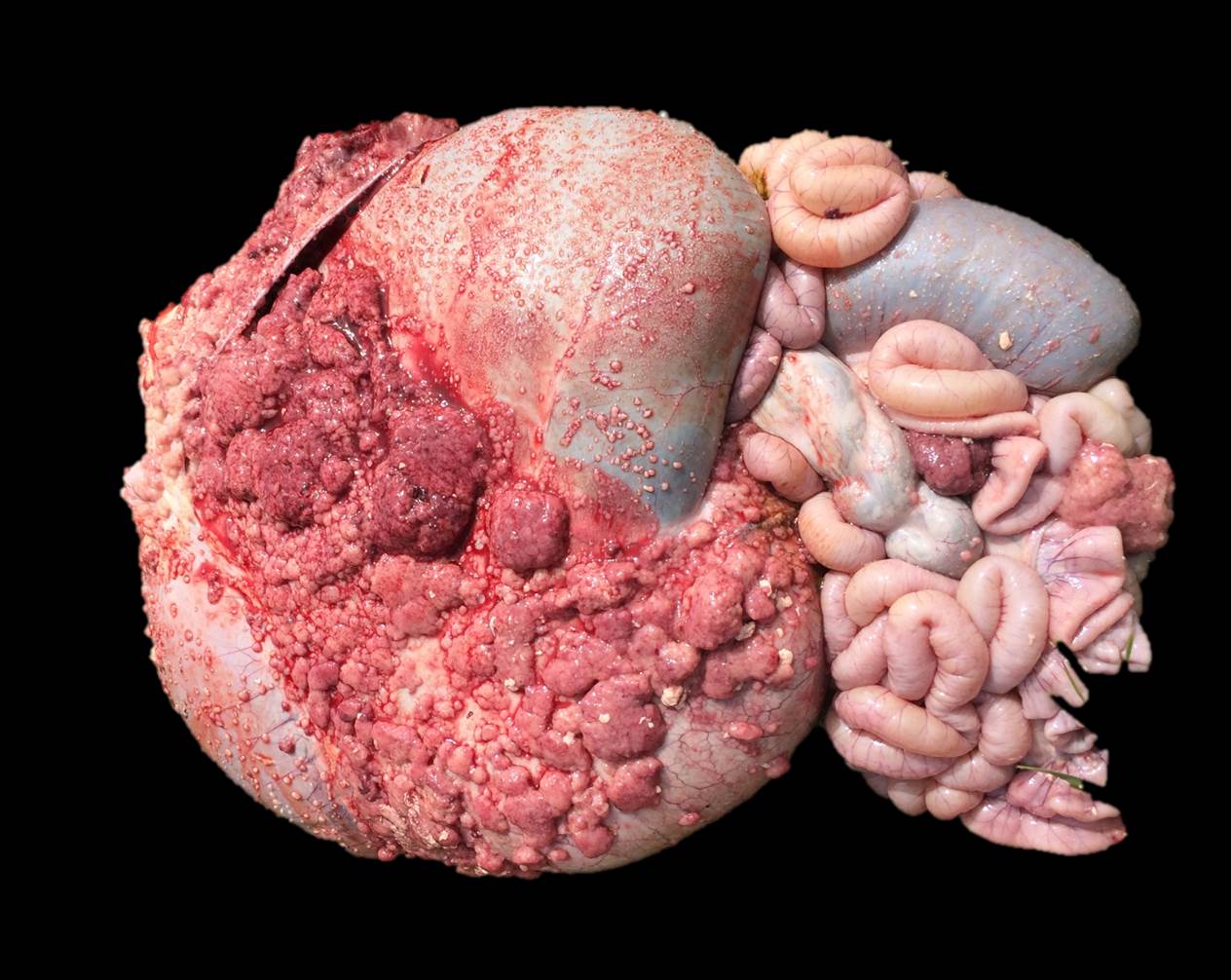

Gross pathological findings included multifocal to coalescing, 2mm-6cm, pink to white nodules scattered over the serosal surface of the abdominal viscera, which extended through the inguinal canal, and were widely dispersed over the tunica vaginalis of the left and right testes. There was gelatinous edema of the scrotal epidermis and tunica dartos, as well as 8-10L of serosanguinous peritoneal effusion, which contained numerous fibrin clots.

Laboratory results:

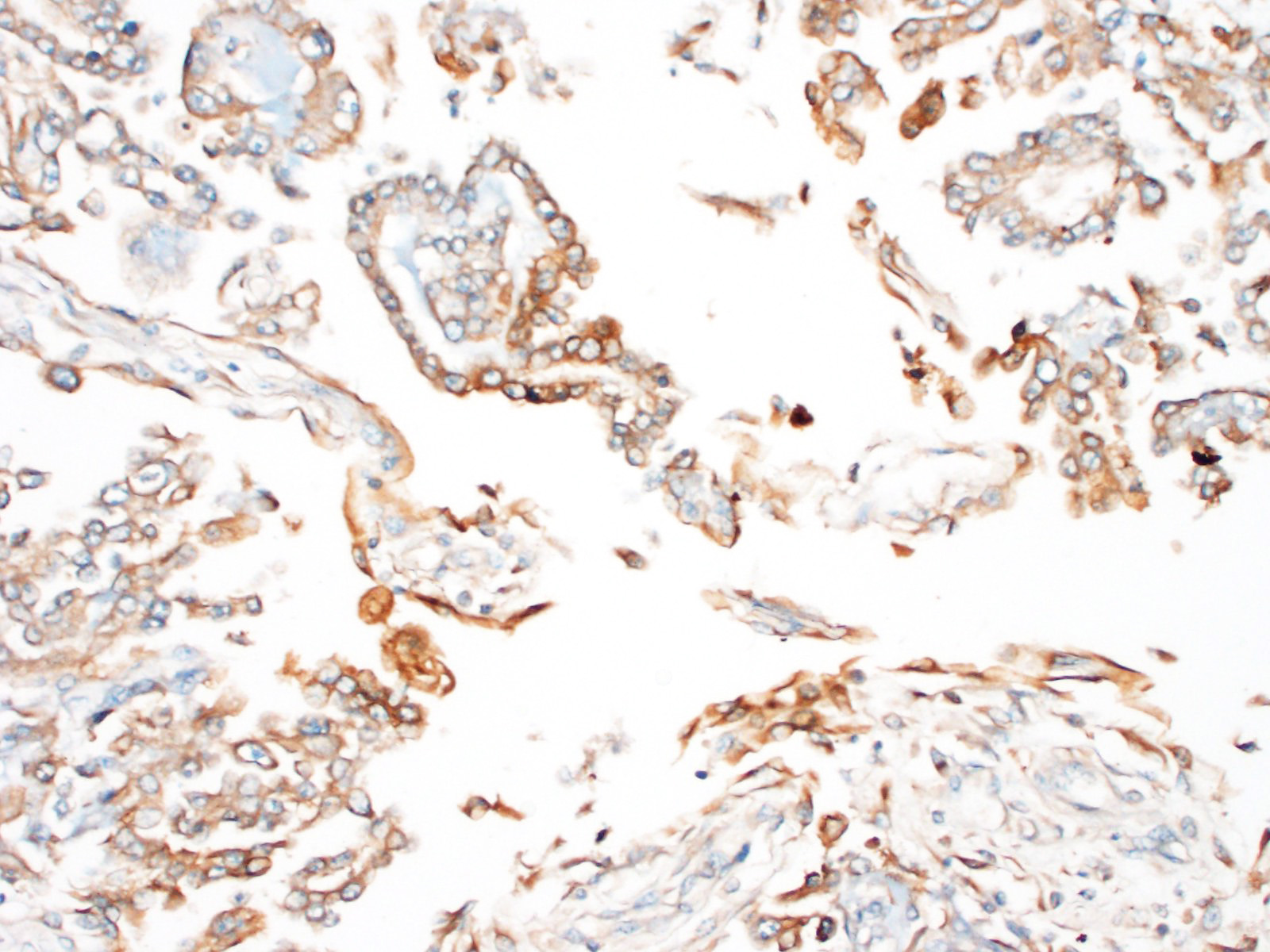

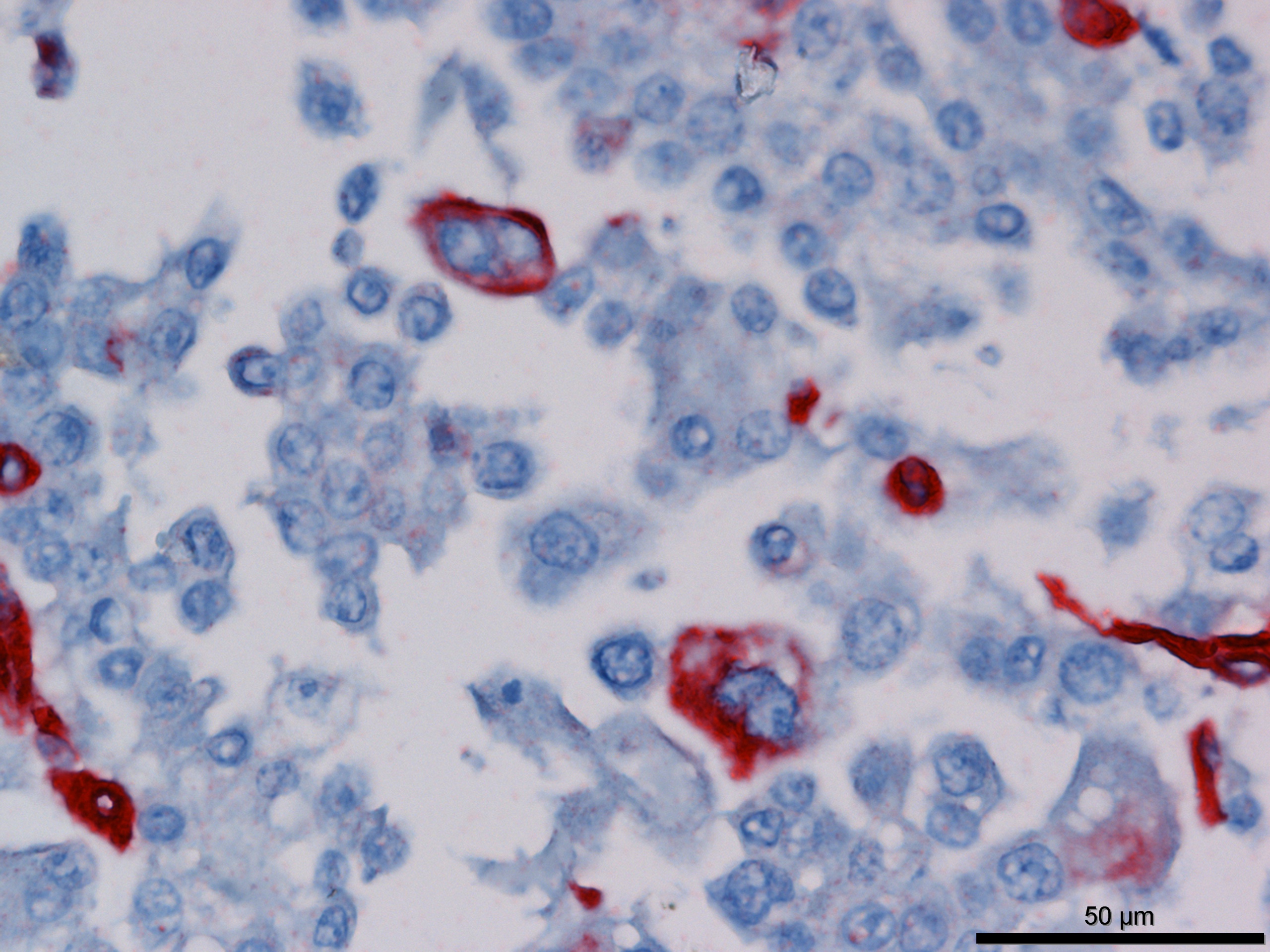

Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positive cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for pancytokeratin antibody clone AE1/AE3. Low numbers of individual or clustered neoplastic cells reacted with the anti-vimentin antibody (clone V9).

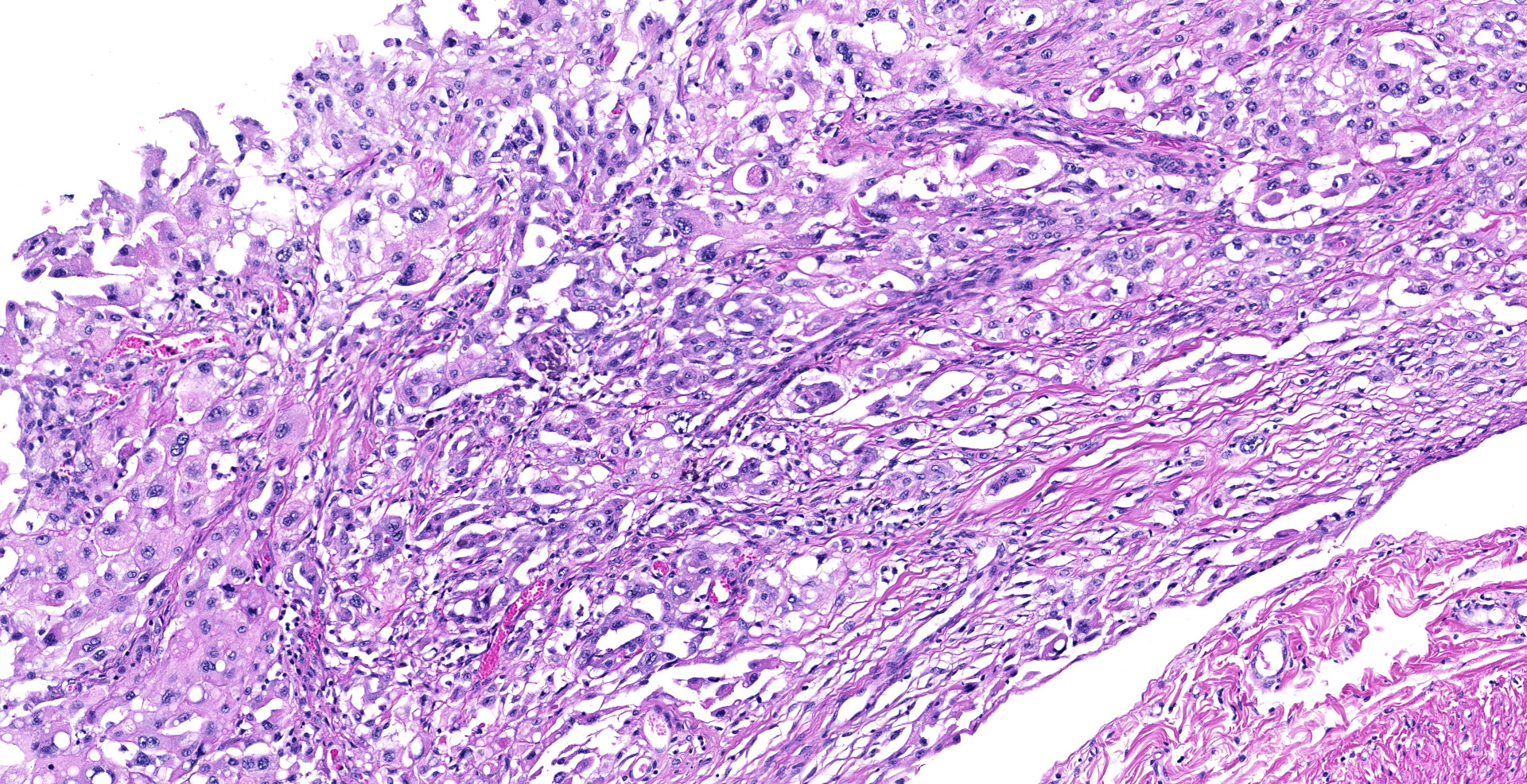

Microscopic description:

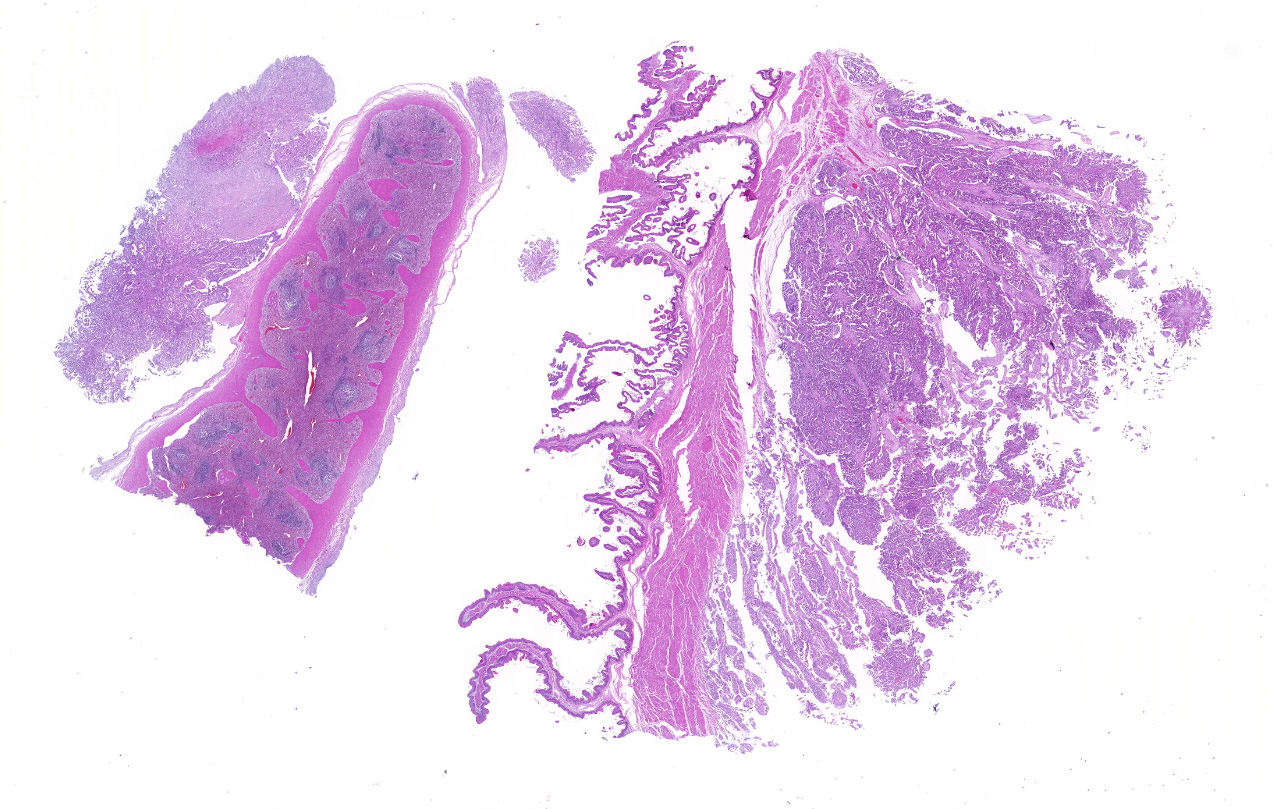

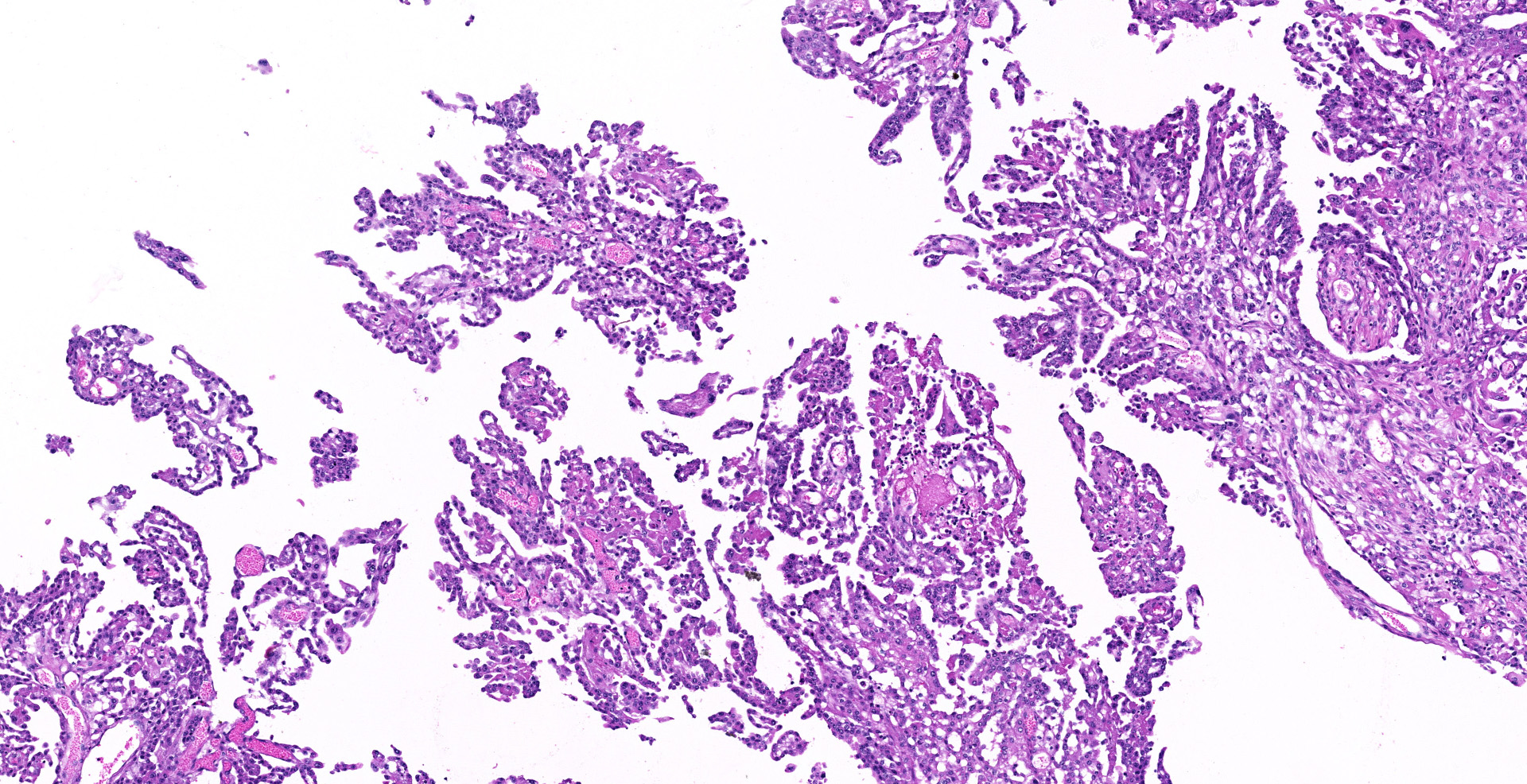

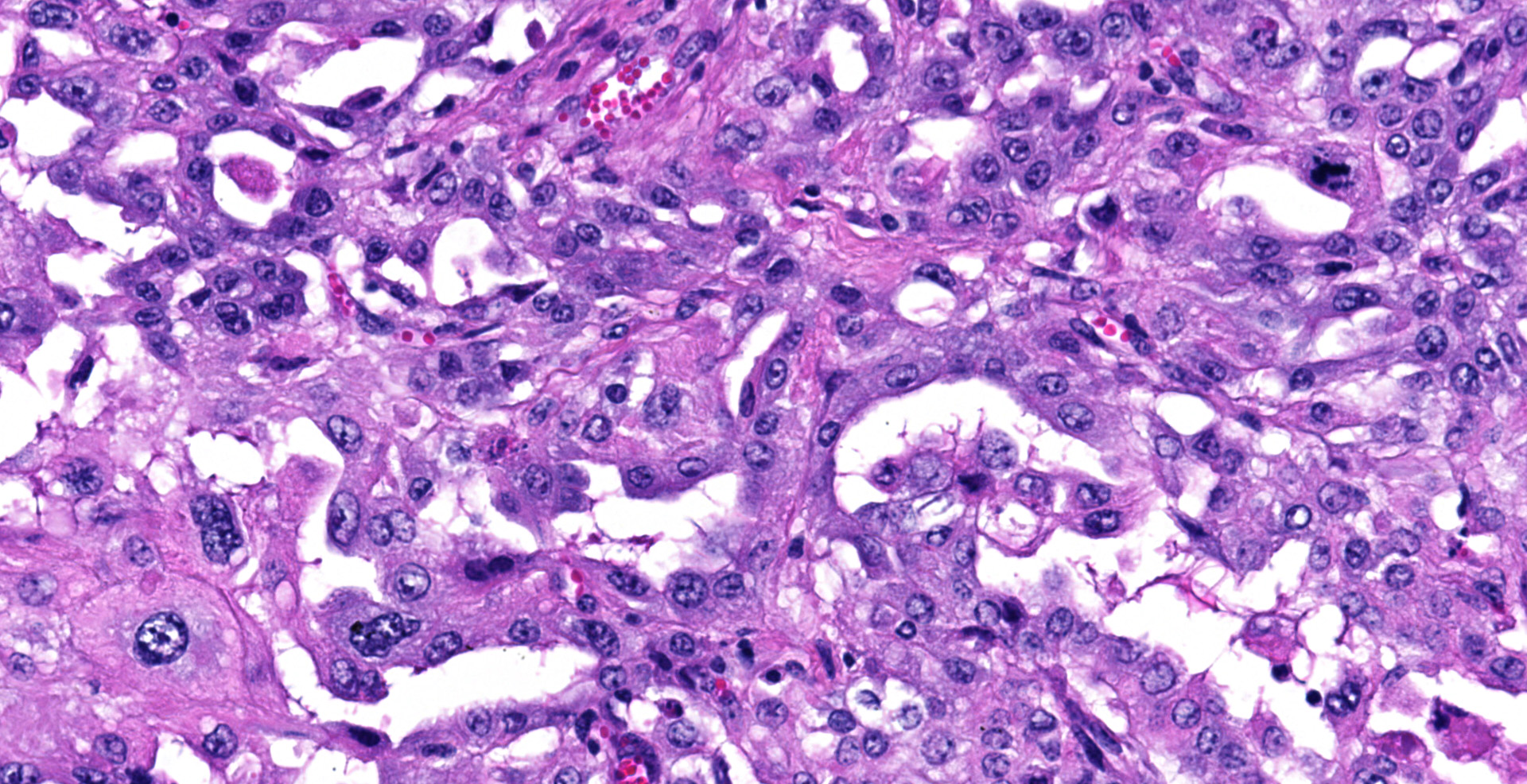

Sections of the forestomachs and spleen were examined histologically. Extending from the serosa of the spleen and forestomachs is a poorly demarcated, unencapsulated, highly cellular population of neoplastic mesothelial cells forming papillary and micropapillary projections, supported by a fine fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells are pleomorphic, polygonal to spindle-shaped, with variably distinct cell borders, a moderate amount of eosinophilic, often vacuolated cytoplasm, round to ovoid central nuclei, vesicular to stippled chromatin and 1-3 nucleoli. There is moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and rare multinucleated cells (up to 4 variable sized nuclei) with evidence of nuclear molding. The mitotic rate is 2 per 40X HPF. Scattered neoplastic cells are hypereosinophilic, shrunken and have pyknotic nuclei (necrosis). There are occasional small aggregates of lymphocytes and rare neutrophils scattered through the neoplastic cells.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Rumen and spleen: Peritoneal mesothelioma, epithelioid, Friesian, Bovine.

Contributor's comment:

Mesotheliomas are rare in all domestic animals, most commonly reported in cattle and notable as a congenital tumor of calves. They are also described in dogs, cats, horses, rats, and more recently in wildlife species including skunks, Amazon Parrots and jaguars. 8,9,14

Mesotheliomas may arise on the pleura, pericardium, and peritoneum (including tunica vaginalis of the testes). Most bovine mesotheliomas are peritoneal, with ascites as the primary presenting clinical sign.12 In fetal cases, this can lead to dystocia.10 Congenital tumors have been described as those discovered in fetuses or in calves younger than two months of age.11

Mesothelial cells secrete serous fluid,3 as well as performing homeostatic and innate immune functions. Mesotheliomas spread readily by seeding, so are usually considered malignant,12 although lymphatic metastasis and direct invasion also occur. Scrotal tunica vaginalis involvement is reported in rats, dogs, humans and bulls, including rare historical reports of congenital cases in calves.1

Histological classifications include epithelioid (cuboidal cells forming papillary projections over a fibrovascular core), sarcomatous (spindle-shaped cells) and biphasic (mixed) patterns. Epithelioid tumors are further divided in animals into those with non-neoplastic scirrhous proliferation with sparse neoplastic mesothelial cells (sclerosing mesotheliomas), or those predominantly composed of neoplastic cells forming cystic, tubular, solid, deciduoid or papillary structures.12 Papillary is the most common subtype. The stroma can have chondroid or osseous differentiation, evidence of the multipotency of mesothelial cells.6

Differential diagnoses include metastatic carcinoma and hyperplastic (reactive) mesothelium. It is very difficult to distinguish between mesothelioma and hyperplasia cytologically,12 because reactive mesothelial cells can share the large nucleoli, binucleation and mitotic figures of their neoplastic counterparts. Mesotheliomas may have indistinct vacuoles, compared to crisper vacuoles suggestive of adenocarcinoma.4 Similar to adenocarcinomas, histologically epithelioid mesotheliomas form tubules, papillae, trabeculae and can form pseudoacini containing basophilic extracellular material. If these cells have columnar shape and eccentric nuclei, adenocarcinoma should be considered.

Mesotheliomas secrete Alcian-Blue-positive hyaluronic acid in their cytoplasm and stromal matrix. After removal by pre-treatment with hyaluronidase, this delineates mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma (which remains Alcian-blue-positive, due to its neutral mucin).

Immunohistochemical staining of mesotheliomas is positive for cytokeratin 18 and vimentin. Calretin positivity indicates likely mesothelioma (particularly biphasic) over adenocarcinoma, along with carcinoembryonic antigen negativity (CEA- human only).

Ultrastructure is also helpful in distinguishing between carcinoma and many mesotheliomas, because epithelioid mesotheliomas have plentiful, long, sometimes branching microvilli over most of their surface, and circumferential nuclear intermediate microfilaments, whereas adenocarcinomas (while they share desmosomes and tight junctions) have few to absent microvilli and no perinuclear microfilaments.6

In humans, mesothelioma is associated with exposure to asbestos, radiation and possibly SV40, and in F344 rats can be induced by vinylidene chloride. Crocodilite, the most oncogenic asbestos fiber, interferes with spindle and chromosome motion in mitosis, which is thought to cause translations, deletions and aneuploidy.7

Ferruginous bodies have been identified in the lungs of cattle and dogs with mesothelioma, however in many other domestic animal cases there were no asbestos bodies and no historical exposure. Asbestos bodies can be difficult to identify by light microscopy.6

In F344/N rats, gene expression of spontaneous mesotheliomas showed downregulation of tumor suppressors PTEN and TP53 and GADD45, along with overexpression of an anti-apoptotic BCl mediator (Bcl12a1) and downregulation of pro-apoptotics BAX, and Fadd and Fas mediators. These rats also had upregulation of growth factors TGF? and TGF ?, IGF, p38MAPK and NFKB. Interestingly, there was also paradoxical downregulation of cell cycle mediators MYC and JUN.2

Contributing Institution:

Massey University

Institute

of Veterinary, Animal and Biomedical Sciences

Private Bag 11 222

Palmerston North 4442

New Zealand

JPC diagnosis:

Serosa, reticulum and spleen: Mesothelioma, papillary type, Friesian, bovine.

JPC comment:

There may be tissue variation between slides. The images captured at JPC were from the affected reticulum, but there may be slides of rumen as well.

The contributor provides a concise narrative about mesothelioma and touches on some of the molecular pathogenesis of this disease. A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease (ADAM) transmembrane proteases, and specifically ADAM10, are overexpressed in several cancers. A critical aspect of ADAM10 is its sheddase activity, which can cleave growth factors, receptors, and adhesion proteins, which each play important roles in tumor progression. ADAM10 can cleave CD44, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and L1 adhesion molecules, an ability correlated with neoplastic cell migration and invasion. Using in vivo mouse models, using siRNA to deplete ADAM10, migration of malignant mesothelial cells was decreased, presenting a potential treatment strategy.13

Ferroptosis is a pathway of cellular death that involves iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, with glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) the central regulator. Dysregulation of ferroptosis has been implicated in ischemic organ damage and cancer. Inhibition of GPX4 can directly facilitate ferroptosis, which contributes to the antitumor function of p53, BAP1, and fumarase. Ferroptosis can be regulated by cadherin-mediated NF2 and Hippo signaling pathways. Interruption of these pathways allows the proto-oncogenic transcriptional co-factor YAP to promote ferroptosis. A recent mouse model of malignant mesothelioma showed that inactivation of NF2 rendered neoplastic cells more sensitive to ferroptosis, revealing the NF2-YAP signaling as a potential area of treatment.15

In the field of artificial intelligence, classification is one of the most basic tasks performed regularly. One simple example of classification is the spam filter used to classify emails using natural language processing and other characteristic signatures. A neural network is a series of nodes between an input and output, with weights associated with transitions between nodes. The end result is a model that will classify the input into designated output categories. There is tremendous efficiency and capability variation of neural networks determined by the number of nodes, forward or backward propagation, supervised versus unsupervised learning, and other statistical differences. Often the different nodes, or groups of nodes, can be correlated to specific decision criteria. A French research project, MesoNet, leveraged the data from MESOBANK and created a neural network to classify whole slide images of malignant mesotheliomas in humans. They were able to correlate decision points to histologic features, such as inflammation in the stroma, cellular diversity, and vacuolization. By correlating the classifications with patient mortality data, it was determined that the model was more accurate in predicting patient survival than current pathology practice. While nearly 3000 cases of independent malignant mesotheliomas were required to build this neural network, if overtraining is avoided, models such as this may have sufficient transportability for use in other facilities and other datasets.5

References:

1. Baskerville A: Mesothelioma in calf. Pathologia Veterinaria 1967:4(2):149-+.

2. Blackshear PE, Pandiri AR, Ton T-VT, Clayton NP, Shockley KR, Peddada SD, et al.: Spontaneous Mesotheliomas in F344/N Rats are Characterized by Dysregulation of Cellular Growth and Immune Function Pathways. Toxicologic pathology 2014:42(5):863-876.

3. Brower A, Herold LV, Kirby BM: Canine Cardiac Mesothelioma with Granular Cell Morphology. Veterinary Pathology 2006:43(3):384-387.

4. Butnor KJ: My approach to the diagnosis of mesothelial lesions. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2006:59(6):564-574.

5. Courtiol P, Maussion C, Moarii M, et al. Deep learning-based classification of mesothelioma improves prediction of patient outcome. Nature Medicine. 2019;25:1519-1525.

6. Head KW: Histological classification of tumors of the alimentary system of domestic animals: Published by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in cooperation with the American Registry of Pathology and the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Worldwide Reference on Comparative Oncology, 2003.

7. Jeffrey G. Ault RWC, Cynthia G. Jensen, Lawrence C. W. Jensen, Lori A. Bachert, and Cozily L Rieder: Behavior of Crocidolite Asbestos during Mitosis in Living Vertebrate Lung Epithelial Cells. CancerResearch 1995:55:792-798.

8. Kim S-M, Oh Y, Oh S-H, Han J-H: Primary diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma in a striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis). Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2016:78(3):485-487.

9. McCleery B, Jones MP, Manasse J, Johns S, Gompf RE, Newman S: Pericardial Mesothelioma in a Yellow-naped Amazon Parrot (Amazona auropalliata). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 2015:29(1):55-62.

10. Misdorp W: Congenital tumours and tumour-like lesions in domestic animals. 1. Cattle - A review. Veterinary Quarterly 2002:24(1):1-11.

11. Misdorp W: Tumours in calves: Comparative aspects. Journal of Comparative Pathology 2002:127(2-3):96-105.

12. Munday JS, Löhr CV, Kiupel M: Tumors of the Alimentary Tract Tumors in Domestic Animals: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016: 499-601.

13. Sepult C, Bellefroid M, Rocks N, et al. ADAM10 mediates malignant pleural mesothelioma invasiveness. Oncogene. 2019;38:3521-3534.

14. Souza FDL, de Carvalho CJS, de Almeida HM, Pires LV, Silva LD, Costa FAL, et al.: Peritoneal mesothelioma in a jaguar (Panthera onca). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2013:44(3):737-739.

15. Wu J, Minikes AM, Gao M, et al. Intercellular interaction dictates cancer cell ferroptosis via NF2-YAP signalling. Nature. 2019;572:402-406.