Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 12

12 December, 2018

CASE I: 065/Case 1 (JPC 4049888)

Signalment: Juvenile female common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus).

History: Two juvenile common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) from the German Primate Center were presented to the veterinarian. They showed depression, pyrexia, anorexia, and multiple facial skin ulcerations. Neither animal responded to antibiotic and analgesic treatment and both developed severe neurological signs including clonic seizures, disorientation, and circular movements before they died within few days after disease onset.

Gross Pathology: Both monkeys revealed multiple erosions and ulcerations of the facial skin, especially at mucocutaneous junctions, and on the tongue. Lingual lesions presented as multifocal to coalescing dark red mucosal indentations with distinct, variably raised margins, measuring between 0.5 and 1 cm in diameter, and sometimes covered by a fibrinosuppurative exsudate. Besides severe lymphadenopathy of the associated mandibular and cervical lymph nodes and mild splenomegaly, no other gross lesions were detected.

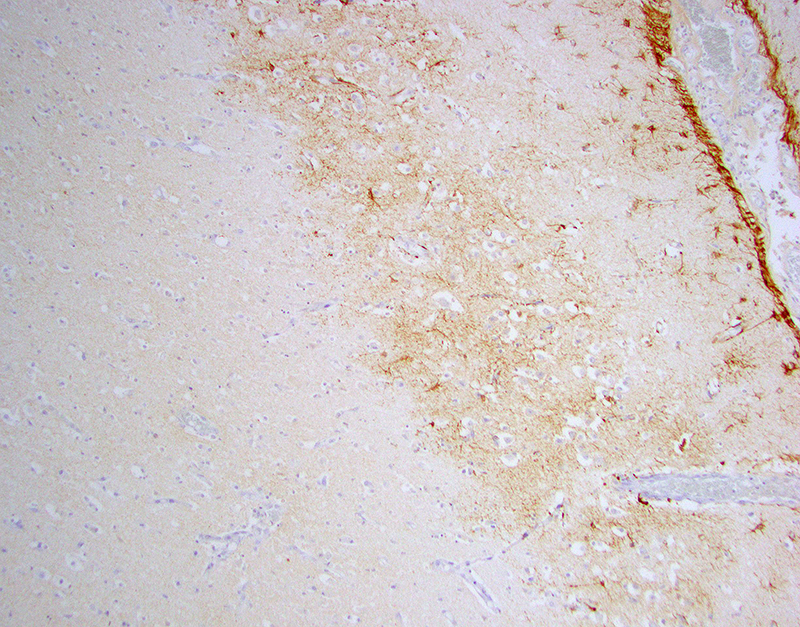

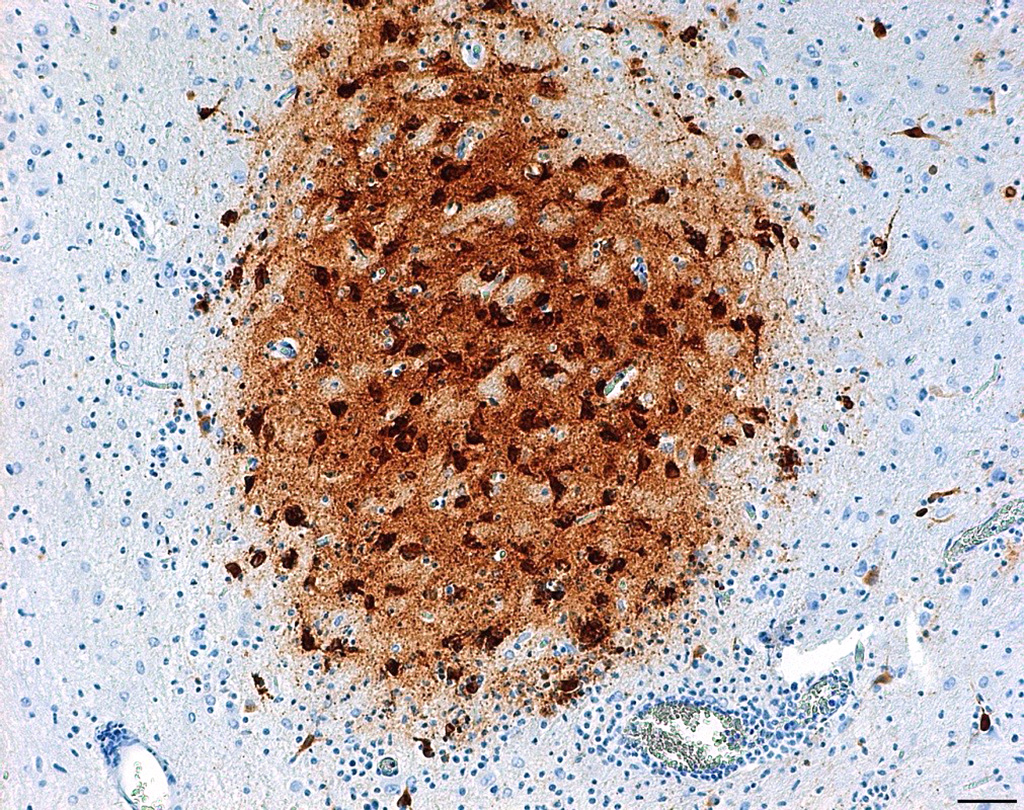

Laboratory results: Brain, tongue and skin tissues were positive for HHV1 antigen, detected by immunohistochemistry (particularly in central neurons and keratinocytes).Transmission electron microscopy revealed numerous l herpes virions with characteristic electron-dense core, capsid and envelope in cutaneous keratinocytes.

Microscopic Description:

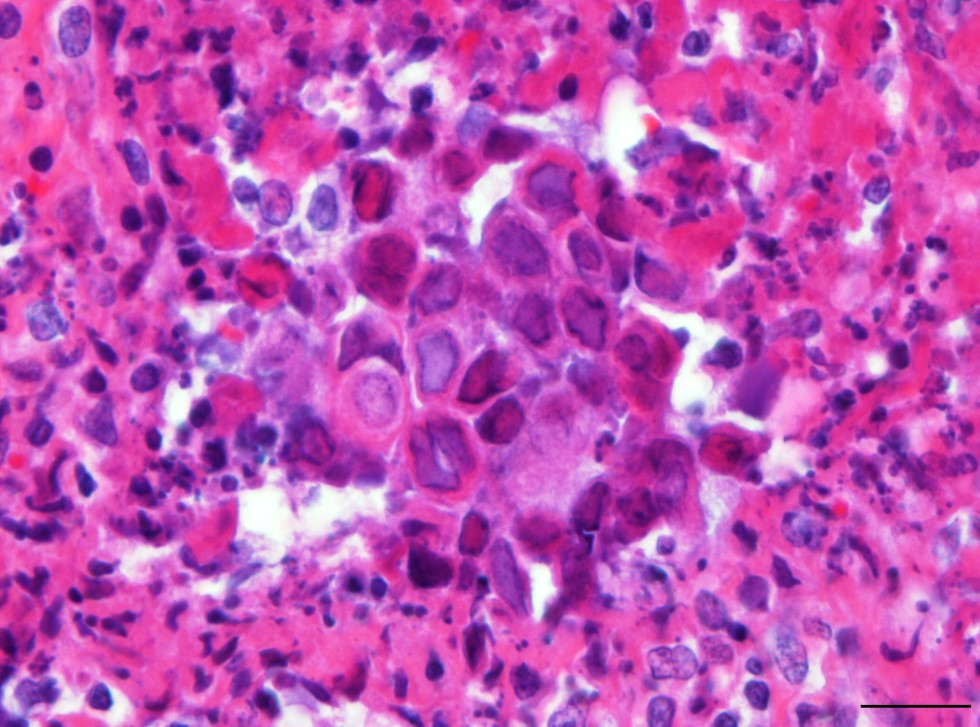

Brain: Multifocally throughout the grey and to a lesser extend in the white matter of cerebrum, brainstem and cerebellum, there are mild to moderate inflammatory foci, either concentrated around blood vessels (perivascular cuffing) or scattered within the neuropil. The inflammatory infiltrate consists of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and fewer plasma cells, often admixed with mild karyorrhexis, karyolysis and pyknosis (necrotic neutrophils). The affected neuropil in addition reveals mild to moderate scattered to nodular gliosis and several shrunken, angular and hypereosinophilic neurons with hyperchromatic nuclei (neuronal necrosis).Within very few glia cells and degenerate neurons, there are conspicuous large basophilic intranuclear inclusions, which marginate the chromatin. Perivascular cuffing is often associated with mild endothelial hypertrophy. Meningeal blood vessels are often engorged with erythrocytes (hyperemia) together with moderate to marked intravascular stasis of leucocytes, mainly neutrophils, and multifocal mild to moderate perivascular inflammatory infiltration as previously described. Multifocally within the cerebral white matter, there is also mild to moderate dilation and vacuolation of Virchow-Robin spaces (edema).

Tongue: There is multifocal to coalescing ulceration of the lingual surface with the extensively lost mucosal epithelium being replaced by a thick serocellular crust composed of fibrin, varying amounts of viable and degenerate neutrophils and multifocal coccoid bacterial colonies. In areas with less extensive ulceration, circumvallate papillae are multifocally expanded by intraepithelial clefts filled with variable amounts of viable and degenerate neutrophils, fibrin, edema, and few acantholytic keratinocytes (vesicopustules). Ulcerations and pustules are multifocally flanked by groups of degenerate or necrotic keratinocytes, often bearing large eosinophilic to amphophilic, homogenous intranuclear inclusions with marked margination of chromatin. The adjacent epithelium is mild to moderately hyperplastic, characterized by acanthosis and intracellular edema. Fibrin, mild hemorrhage and edema together with varying numbers of neutrophils, histiocytes, fewer lymphocytes and plasma cells moderately expand the adjacent subepithelial connective tissue and separate superficial skeletal muscle fibers and individual myocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Central nervous system:

Cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem: Meningoencephalitis, lymphohistiocytic and neutrophilic, multifocal, moderate, subacute with neuronal necrosis, gliosis and very few glial and neuronal homogenous basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies; common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), nonhuman primate.

Tongue:

Glossitis, vesicopustular to ulcerative, multifocal to coalescing, subacute, marked with fibrinous to serocellular crusting and epithelial homogenous eosinophilic to amphophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies; common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), nonhuman primate.

Contributor’s Comment: Herpesviridae are global pathogens of almost every vertebrate species. In their natural hosts, they do not cause fatal disease, but cross-species infection can cause acute death 1,10.

Infection with Human Herpesvirus 1 (HHV1), an alphaherpesvirus, leads to mild mucosal lesions or an inapparent course in the natural host (human).9,13 Fatal encephalitis and/or systemic disease can occur in neonates or immune compromised individuals.7,14 In humans, infection with HHV1 persists lifelong because of viral latency in sensory neurons. When immunity is compromised through stress or disease, it becomes activated through suppression of the latency-associated transcript gene.11 It can be shed even in the absence of visible lesions.

Several nonhuman primate species are susceptible to infection with human herpesviruses. Old World Primates like gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), bonobos (Pan paniscus), white handed gibbons (Hylobates lar) and chimpanzees (Pan troglotydes), can be naturally infected with HHV1. Although single fatal disease outcomes have been described,2,6 their virus-host relationship seems to be similar to that in humans, as they usually show only mild symptoms (lesions in mucocutaneous tissue, skin, conjunctiva).10

However, New World monkey species and prosimians are highly susceptible to HHV 1 infections. 1,4,5,9,10 Typical lesions in these species are erosions and ulcers of oral mucous membranes, especially the tongue, and mucocutaneous junctions of the lips. Severe necrotizing hepatitis and multifocal nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis often occur in these species.5,10 Thus, in cases of ulcerative skin lesions in nonhuman primates, HHV1 has to be considered as a possible cause and callitrichids represent a highly susceptible species for HHV1 infections.

The exact route of transmission is unknown, but likely occurs via direct mucosal contact, wounds, saliva, maternal milk, contaminated fomites and through airborne and waterborne routes.6 Additionally, direct transmission from latently infected humans to their monkey pets is described.

In the present case, possible sources of virulent HHV1 are animal keepers or visitors. HHV1 specific PCR can be used for antemortem diagnostics to allow appropriate treatment with antiviral drugs. Viral antigen can be detected in histological sections of lesions by immunohistochemistry and Transmission electron microscopy can serve as a useful tool to seek for viral particles.

Contributing Institution:

German Primate Center, Pathology Unit, Kellnerweg 4, 37077 Göttingen, Germany

JPC Diagnosis:

- Tongue: Glossitis, necrotizing, focally extensive, moderate, with ulceration, epithelial syncytia and intranuclear viral inclusions.

- Cerebrum and brainstem: Encephalitis, necrotizing, multifocal, mild to moderate with gliosis, perivascular cuffing, and rare intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent overview of cross-species herpesviral infection, in this case human herpesvirus 1 (human simplex virus 1) and its devastating effects on New World primates.

Cross species infection by alphaherpesviruses has been well known to result in tragic circumstances, via zoonotic and reverse-zoonotic (as seen here) means, as well as between diverse animal species. A review of the literature is replete with interesting cases, some of which are recounted here.

Perhaps the most famous case of interspecies transmission of herpesvirus was described in a case report by Albert Sabin, MD (who would go on to develop the oral polio vaccine) in 1932, who described an ascending paralysis in an accomplished young physician and research colleague following a “monkey bite”. For many years, this researcher was simply known as “W.B”, while the agent isolated from his neural tissue gained great renown as the “B virus” (now known as macacine herpesvirus-1) which has claimed 70% of its known victims over the years due to fatal encephalitis. In 1985, that young researcher’s name was finally published, Dr. William Barlett Brebner (1903-1932).12

Equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) is a well-known pathogen of horses that is known to cause a wide range of disease in its natural host, but may also result in disease in widely disparate mammalian species as well. A 2011 article15 details fatal encephalitides characterized by non-suppurative meningoencephalitis, which were shown to be caused equine herpesvirus 1 in four black bears (Ursus americanus), two Thompson gazelles (Eudorcas thomsoni) and eighteen guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus). In addition, a closely-related herpesvirus, equine herpesvirus-9 (EHV-9), thought to have originated in the plains zebra (Equus burchelli), has been known to cause fatal encephalitis in polar bears.3 Pseudorabies virus (Suid herpesvirus-1) is another alphaherpesvirus with a wide host range. Primarily infecting swine (who are the natural reservoir), secondary mammalian hosts abound, including cattle, horses, dogs, mink, and cats. Human infection, although possible in immunocompetent humans has been limited to non-fatal conditions.

One final tragic cross-species herpesviral infection has resulted in the depth of over 100 young captive and wild Asian elephants from a rapid-onset, acute hemorrhagic disease caused primarily by multiple distinct strains of two closely related chimeric variants of a novel herpesvirus species designated elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV1A and EEHV1B). These and two other species of Probosciviruses (EEHV4 and EEHV5) are evidently ancient and also result in commonly asymptomatic infections of adult Asian. Although only a few similar cases have been observed in African elephants, they harbor similar viruses—EEHV2, EEHV3, EEHV6, and EEHV7—have been isolated in African elephants in lung and skin nodules or saliva. For reasons not yet understood, approximately 20% of Asian elephant calves appear to be susceptible to the disease when primary infections are not controlled by normal innate cellular and humoral immune responses.8

References:

- Costa EA, Luppi MM, Malta Mde C et al. Outbreak of human herpesvirus type 1 infection in nonhuman primates (Callithrix penincillata). J Wildl Dis. 2011;47:690-693.

- Emmons RW, Lennette EH: Natural herpesvirus hominis infection of a gibbon (Hylobates lar). Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1970; 31:215-218.

- 3. Greenwood AD, Tsangaras K, Ho SYW, Szentiks CA, Nikolin VM, Ma G, Daminani A, East ML, Lawrenz A, Hofer h, Oserrieder N. A potentially fatal mix of herpes in zoos. Curr Biol 2012; 22:1727-1732.

- Huemer HP, Larcher C, Czedik-Eysenberg T, Nowotny N, Reifinger M. Fatal infection of a pet monkey with Human herpesvirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:639-642.

- Juan-Salles C, Ramos-Vara JA, Prats N, Sole-Nicolas J, Segales J, Marco AJ. Spontaneous herpes simplex virus infection in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). J Vet Diagn Invest. 1997;9:341-345.

- Kik MJ, Bos JH, Groen J, Dorrestein GM. Herpes simplex infection in a juvenile orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2005;36:131-134.

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gilden DH. The expanding spectrum of herpesvirus infections of the nervous system. Brain Pathol. 2001;11:440-451.

- Long SY, Latimer EM, Hayward GS. Review of elephant endotheliotropic herpesviruses and acute hemorrhagic disease. ILAR J; 2016:56(3):283-296.

- Longa CS, Bruno SF, Pires AR, et al. Human herpesvirus 1 in wild marmosets, Brazil, 2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1308-1310.

- Mätz-Rensing K, Jentsch KD, Rensing S, et al. Fatal herpes simplex infection in a group of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Vet Pathol. 2003;40:405-411.

- Perng GC, Jones C, Ciacci-Zanella J, et al. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science. 2000;287:1500-1503.

- Pimmentel JD. Past professive: Herpes B virus – “B” is for Brebner: Dr. William Barlet Brebner (1903-1932), Can Med Assoc J 2018: 178(6):726.

- Schrenzel MD, Osborn KG, Shima A, Klieforth RB, Maalouf GA. Naturally occurring fatal herpes simplex virus 1 infection in a family of white-faced saki monkeys (Pithecia pithecia pithecia). J Med Primatol. 2003;32:7-14.

- Whitley RJ, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet. 2001;357:1513-1518

- Wohlsein P, Lehmbecker A, Spitzbarth I, Algermissen D, Baumgartner W, Boer M, Kummrow M, aas L, Grummer B. Fatal epizootic equine herpesvirus 1 infections in new and unnatural hosts. Vet Microbiol 2011 149(3-4):456-460.