Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 12, Case 2

Signalment:

9-year-old FS Chihuahua (dog, Canis lupus familiaris)History:

Gross Pathology: This was a 2 x 1.5 x 1.5 cm, tan, firm, subcutaneous mass from the left axilla. It was not overtly associated with a mammary gland.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

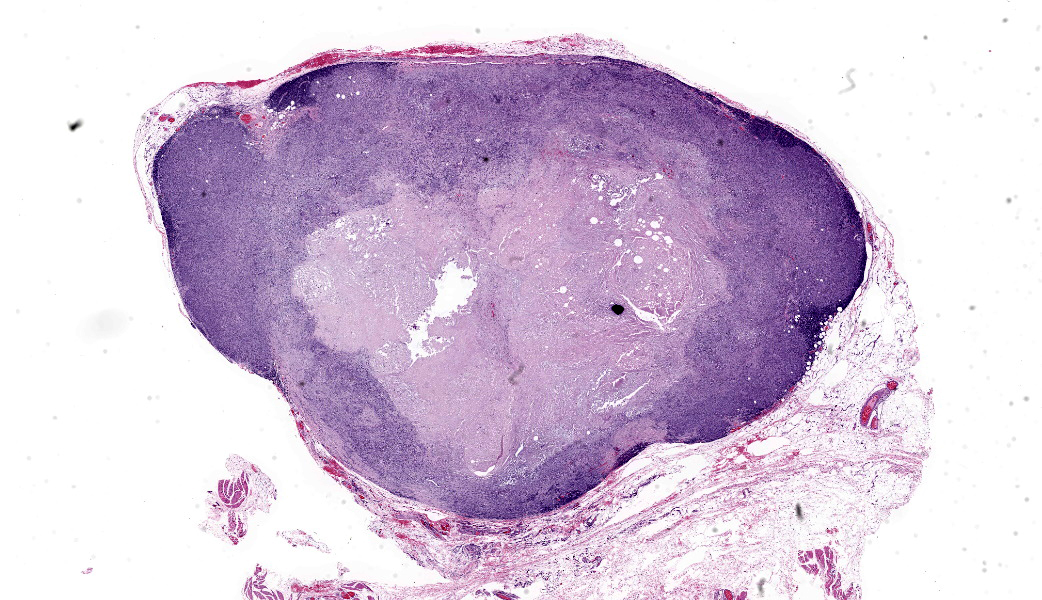

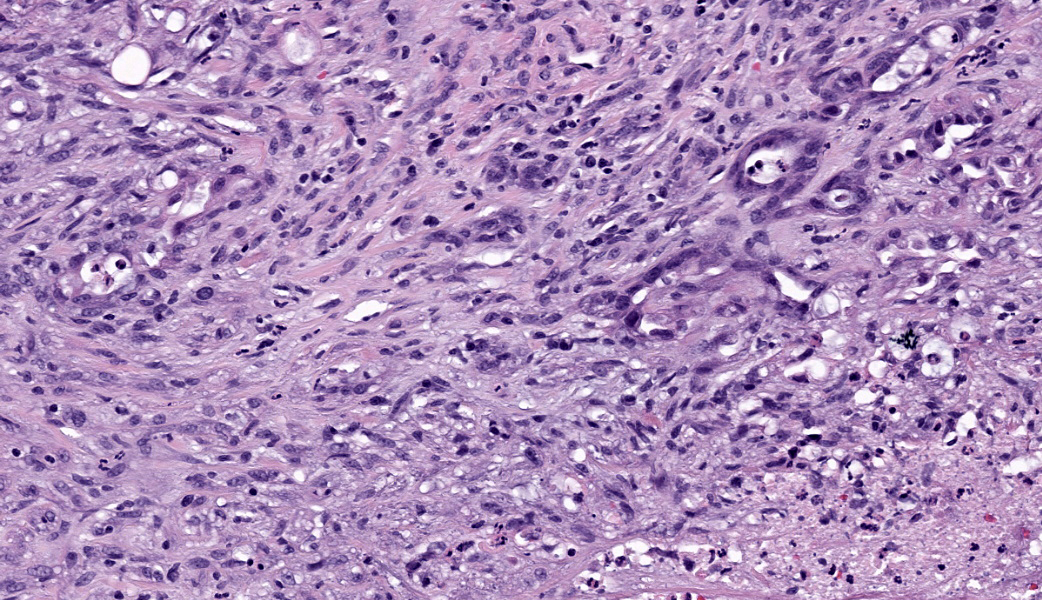

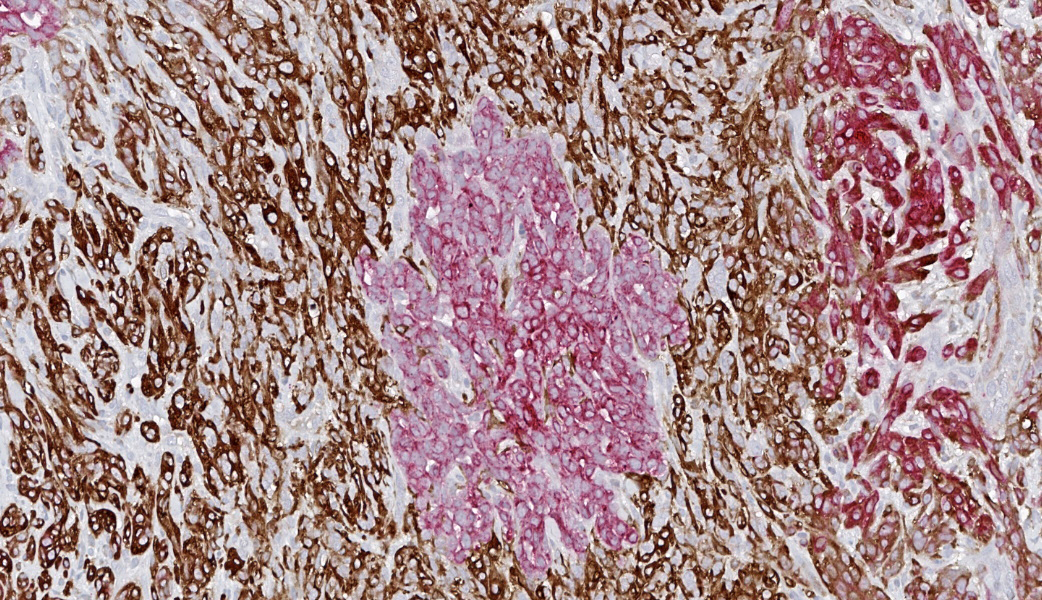

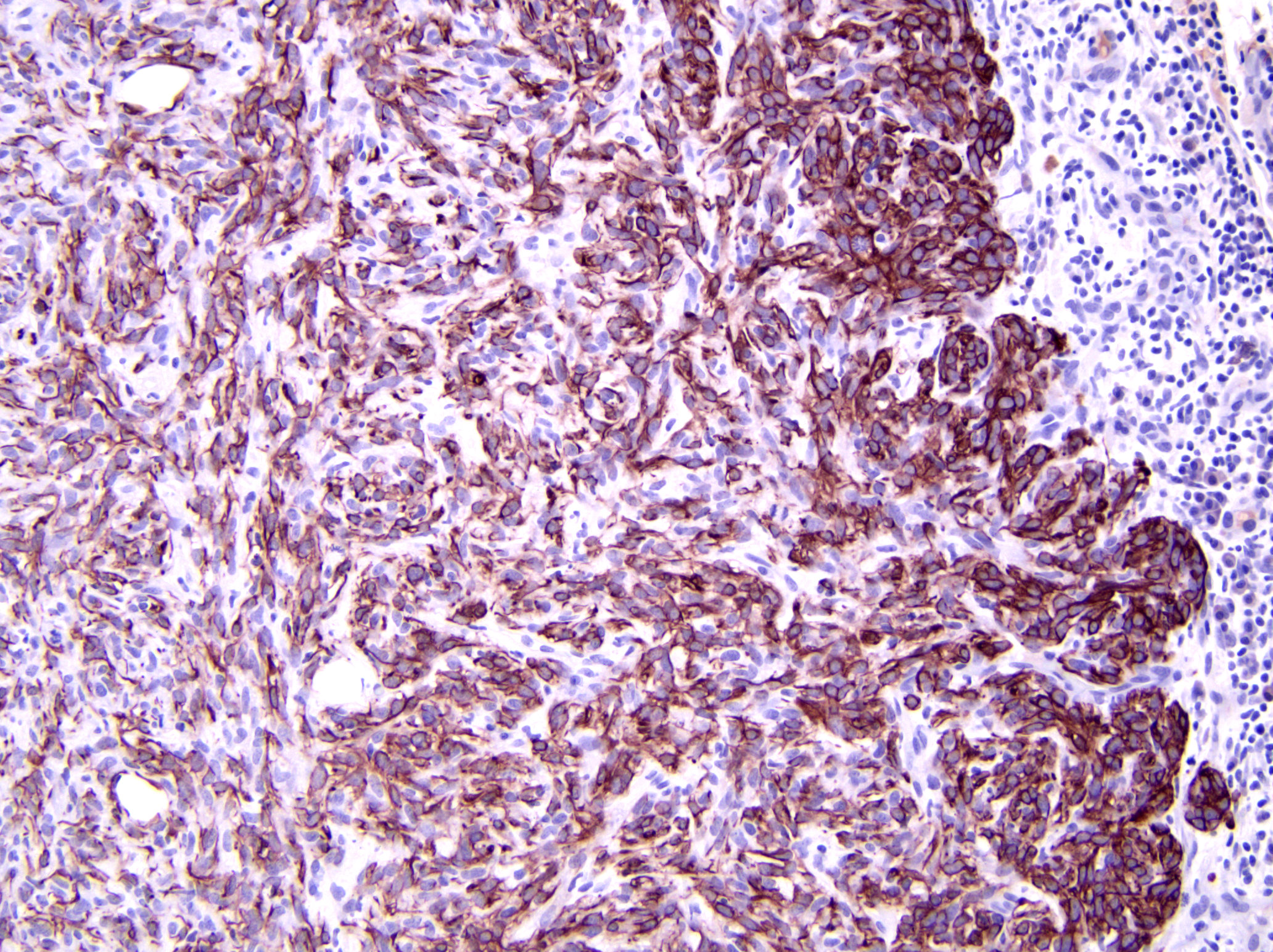

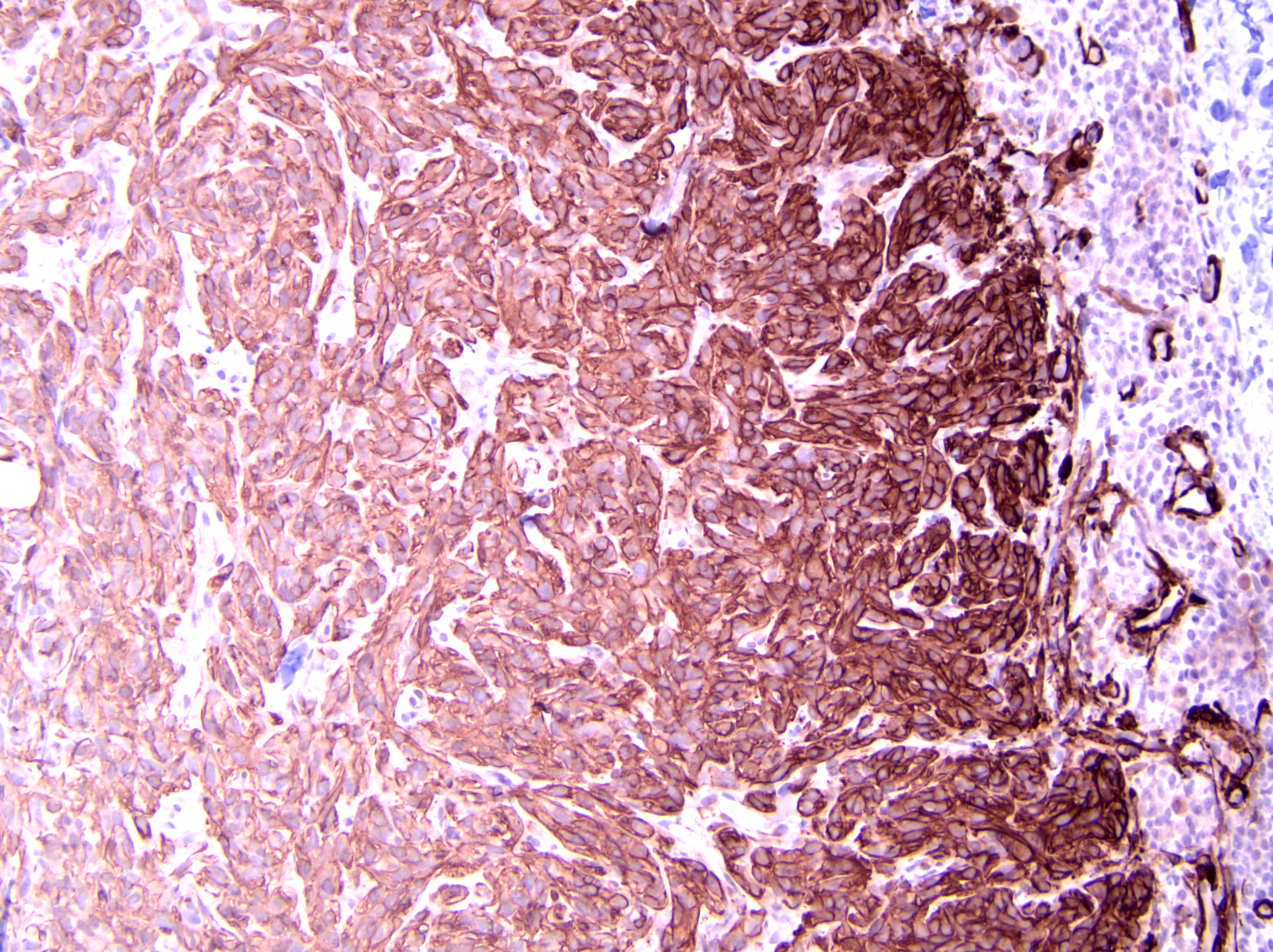

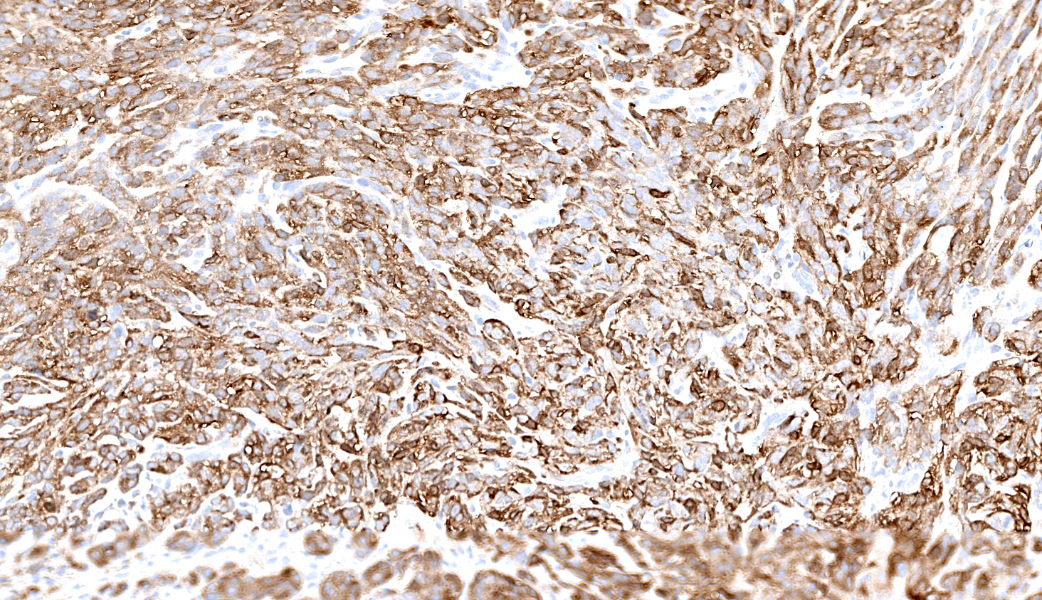

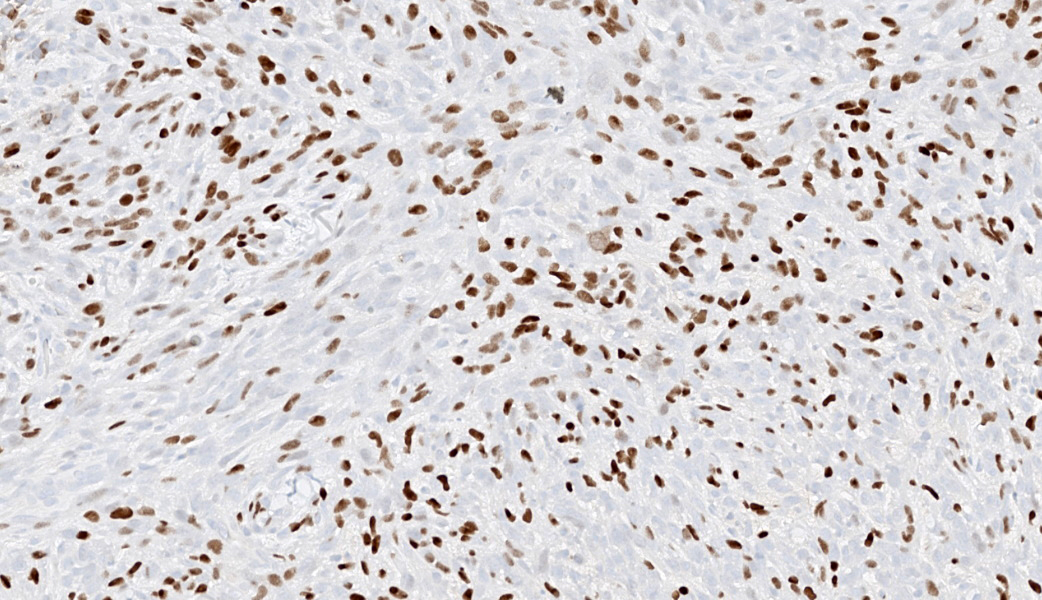

Axillary mass: Examined are two sections of haired skin and mammary tissue containing an encapsulated structure rimmed by lymphocytes (lymph node, presumptive) that is 95% effaced by a large neoplasm composed of two cell populations. The first, and most numerous, population consists of spindle-shaped cells arranged in haphazard bundles and whorls immersed in a pale basophilic matrix and supported by a fine fibrovascular stroma. These cells have indistinct borders and a moderate amount of wispy to vacuolated pale basophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are ovoid to elongate with evenly dispersed chromatin and 1-2 indistinct nucleoli. Anisokaryosis is moderate. The second population consists of polygonal cells arranged in tubules. This population has more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, but the nuclear morphology is nearly identical to the first population. Mitoses are 34 in 2.37 mm², including bizarre mitoses. There is extensive central necrosis of the mass, which abuts the surgical margin of the submitted tissues.Immunohistochemistry results: The polygonal cell population exhibits strong, diffuse membranous and cytoplasmic positivity for MNF116 (pancytokeratin). This population is negative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), consistent with epithelial cells. The spindle cell population exhibits moderate to strong, predominantly membranous positivity for MNF116, as well as moderate to strong membranous and cytoplasmic positivity for SMA, consistent with myoepithelial cells. There is a smaller group of streaming spindle cells that are negative for MNF116 and positive for SMA, consistent with myofibroblasts (desmoplastic response). Controls stain appropriately.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Axillary mass: Mammary carcinoma and malignant myoepithelioma, grade IIContributor's Comment:

The diagnosis of canine carcinoma and malignant myoepithelioma (CAMM) was first introduced in the review article Classification and Grading of Canine Mammary Tumors (2011) by M. Goldschmidt, et. al.2 In previous classification systems for canine mammary tumors, any tumor containing both luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells was considered either a complex tumor (without a mesenchymal component) or a mixed tumor (with a mesenchymal component), without differentiating between tumors whose myoepithelial population was benign and those with a malignant myoepithelial component.3,4 Recognizing CAMM as a separate entity in the 2011 classification system required two major changes in our approach to mammary tumors. First, the use of immunohistochemistry (IHC) to accurately characterize and classify mammary tumors became widespread enough that consistently accurate classification of mammary tumors was possible, allowing the behavior of individual tumor types to be studied more closely.2 Secondly, our definition of complex mammary carcinomas evolved to only include those tumors with a benign myoepithelial component, in recognition of the fact that mammary tumors in which both the epithelial and myoepithelial populations are malignant might behave differently than those in which the myoepithelial population is benign.2-4 In fact, a follow-up 2-year prospective study of 229 dogs showed that dogs with CAMM were more than 10 times more likely to experience tumor-related death than dogs with complex carcinoma, validating the decision to separate these two entities.5The myoepithelial cell population in canine complex mammary tumors is positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA), calponin, vimentin, p63, and high molecular weight basal cytokeratins CK5, CK6, and CK14, while the epithelial population expresses luminal cytokeratins CK8, CK18, and CK19.8 Interestingly, the myoepithelial population in CAMM has higher expression of CK5, CK14, SMA, calponin, and p63 (characterized as an “intermediary” or less well-differentiated phenotype), compared to the myoepithelial population in complex carcinoma (which is more similar to that of terminally differentiated myoepithelial cells).6 CAMM myoepithelial cells also have significantly higher Ki67 expression than those in complex carcinoma, in accordance with their more aggressive biological behavior.6 Conversely, the benign myoepithelial population in canine complex mammary carcinomas has been theorized to play a tumor suppressor role, accounting for the better prognosis of complex carcinoma when compared to simple carcinomas that have no myoepithelial component.1,7 However, if this is true, the tumor suppressor activity appears to be a feature specific to terminally differentiated myoepithelial cells, rather than the malignant, intermediary-like myoepithelial population present in CAMM.6

The present neoplasm most likely represents metastasis of a primary mammary carcinoma to the axillary lymph node, which is supported by the patient history, anatomic location of the mass, and the presence of a compressed population of mature lymphocytes enclosed within a thin fibrous capsule, consistent with remnant nodal architecture. However, given the presence of mammary tissue in the adjacent subcutis, the possibility remains that this is a primary tumor arising from mammary tissue in an unusual location (i.e., the axilla). Either way, the morphologic features of the myoepithelial population (pleomorphism, anisokaryosis, and a high mitotic rate, including bizarre mitoses) are consistent with malignancy, supporting a diagnosis of CAMM over complex mammary carcinoma, in which the myoepithelial component is uniform with minimal anisocytosis and anisokaryosis.2

Definitive diagnosis of CAMM requires IHC to confirm the presence of both a myoepithelial and an epithelial component.2 The present mass has three subpopulations of cells with differing immunophenotypes. The first is the luminal epithelial cell population, which is positive for MNF116 and negative for SMA. MNF116 is an antibody that reacts with cytokeratins 5, 6, 8, 17, and possibly 19; thus, it is expected to stain both luminal epithelial cells and myoepithelial cells. The second group of cells, the myoepithelial population, is positive for both MNF116 and SMA, as expected. However, there is a third population, which is composed of streaming spindle cells that are positive for SMA but not MNF116. These cells are consistent with a desmoplastic response characterized by myofibroblast proliferation, which is a feature shared with highly aggressive mammary carcinomas such as anaplastic carcinoma.2

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, University of Missourihttps://vmdl.missouri.edu/

JPC Diagnoses:

Lymph node: Malignant epithelial and spindle cell neoplasm, metastatic.JPC Comment:

This second case stimulated lively discussion amongst participants regarding both anatomic location and diagnosis. Some participants were successfully able to get to lymph node, while others hedged a bit more and felt comfortable with calling it subcutaneous tissue with a particularly immunogenic neoplasm. Either way, it was a tough call, but the presence of a capsule and subcapsular sinuses are what helped push participants off the fence and into Team Lymph Node.MAJ Travis led participants through a “Mammary Neoplasms 101” conversation, covering the major classifications of mammary tumors. These include ductular, simple (involve just neoplastic epithelium), complex (epithelium and myoepithelium), mixed (Epithelium, myoepithelium, and either bone, cartilage, and/or adipose tissue), and myoepithelial. Within each of these are subcategories, but those five main classifications are a “must-know” starting place when working up mammary neoplasms as a pathologist. Current criteria for histologic grading of canine mammary neoplasms includes evaluation of percentage of tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic count.2

Dogs have the highest incidence of mammary neoplasms of any domestic species.2 Luckily for dogs, the majority of these tumors are clinically benign, which contrasts with most other domestic species that have mostly malignant mammary neoplasms. In dogs, these are typically progressive, and development of neoplasia can proceed from ductular or lobular hyperplasia to dysplasia and onwards to neoplasia. Even within benign adenomas, there can be progression to non-invasive adenocarcinoma and further progression to metastatic mammary adenocarcinoma if these neoplasms are left to grow on the affected dog. Mammary sarcomas in dogs are much less common than epithelial neoplasms but are significantly more aggressive and metastatic when they do occur. Additionally, if a dog develops one mammary neoplasm, it is common for multiple others to develop over time. The prognosis for each mass may vary greatly, and different types of mammary tumors can be found in the mammary glands of an individual animal.1,2

On to the difficulty in providing an appropriate morphologic diagnosis. When deciding how to morphologically diagnose WSC cases, the JPC tries to provide a diagnosis that would be achievable from the H&E slide alone (as this is what is available to participants around the world before each conference). As such, and after much deliberation, participants ultimately decided on a diagnosis of metastatic malignant epithelial and spindle cell neoplasm, as there were no exclusively defining features of a mammary-specific neoplasm on the H&E slide. All agreed, however, that the IHC profile of this neoplasm is supportive of the contributor’s diagnosis of canine mammary carcinoma and malignant myoepithelioma (CAMM), especially given the immunoreactivity of the neoplastic cells for calponin and the spindle cells to both p63 and smooth muscle myosin-heavy chain, which is more specific for myoepithelium than just smooth muscle actin. Following these spirited discussions, Dr. Bruce Williams deployed some well-timed humor by asking attendees, “Having never been to a tea party before, is this what people normally talk about?” Probably not, Dr. Williams, probably not.

References:

- Chang SC, Chang CC, Chang TJ, Wong ML. Prognostic factors associated with survival two years after surgery in dogs with malignant mammary tumors: 79 cases (1998-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:1625-1629.

- Goldschmidt M, Peña L, Rasotto R, Zappulli V. Classification and grading of canine mammary tumors. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):117-131.

- Hampe JF, Misdorp W. IX: Tumours and dysplasias of the mammary gland. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;50:111-133.

- Misdorp W, Else RW, Hellmen E, Lipscomb TP. Histologic Classification of Mammary Tumors of the Dog and the Cat, 2nd ser., vol. 7. Armed Force Institute of Pathology and World Health Organization;1999.

- Rasotto R, Berlato D, Goldschmidt MH, Zappulli V. Prognostic significance of canine mammary tumor histologic subtypes: an observational cohort study of 229 cases. Vet Pathol. 2017;54(4):571-578.

- Rasotto R, Goldschmidt MH, Castagnaro M, Carnier P, Caliari D, Zappulli V. The dog as a natural animal model for study of the mammary myoepithelial basal cell lineage and its role in mammary carcinogenesis. J Comp Pathol. 2014;151(2-3):166-180.

- Rasotto R, Zappulli V, Castagnaro M, Goldschmidt MH. A retrospective study of those histopathologic parameters predictive of invasion of the lymphatic system by canine mammary carcinomas. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:330-340.

- Sorenmo KU, Rasotto R, Zappulli V, Goldschmidt MH. Development, anatomy, histology, lymphatic drainage, clinical features, and cell differentiation markers of canine mammary gland neoplasms. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:85-97.