Signalment:

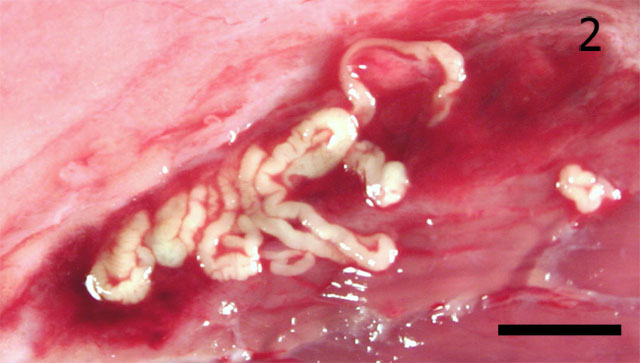

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

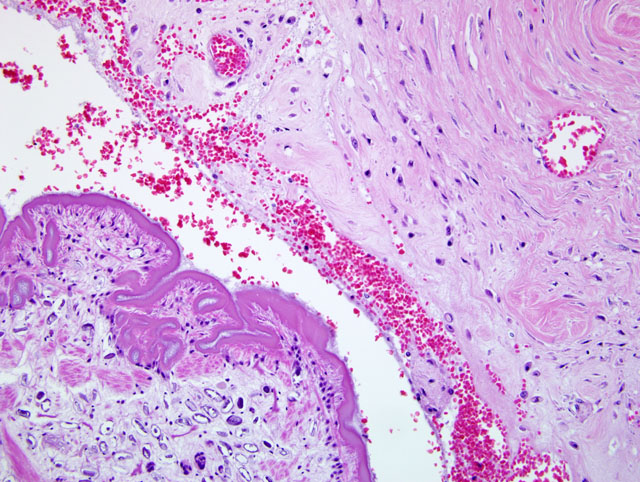

Sparganosis is a disease characterized by the presence of larval pseudophyllidian cestodes in the hosts tissues.(13) Tapeworms may be characterized in tissue sections by the absence of a digestive tract, the presence of a thick layered cuticle with a basement membrane, the presence of calcareous corpuscles, and evidence of a segmented body (4) Plerocercoid larvae are usually solid, club-shaped forms in which scolices and suckers are absent.

Spargana were located in tissue cysts. In histologic sections, there is abundant space around individual spargana (arrows) and the discernible capsule (C) is comprised of eosinophilic amorphous material and relatively few inflammatory cells. Spargana are characterized by invaginations of the tegument resulting in segmentation. Columnar subtegumentary cells form a row beneath the densely eosinophilic tegumentary syncytium, which is covered by a row of dense microtriches. The body is comprised of evenly distributed loose parenchyma with calcareous corpuscles (arrowheads), muscle fibers (M), and excretory ducts (E). Muscle fibers are loosely arranged in a discontinuous row that is oriented parallel to the tegument. Scolices or suckers are not evident.Â

There are two forms of sparganosis: non-proliferative and proliferative.(7,10) Most infections are of the non-proliferative type associated with the presence of a single larva of either Spirometra erinaceieuropaei or Spirometra mansonoides. Proliferative sparganosis is caused by the asexual replication of larvae of Sparganum proliferum in host tissues and the migration of these larvae to new tissues where they grow and repeat the process, ultimately resulting in the death of the host.(3) In 2001, Sparganum proliferum was identified phylogenetically as a new species in the order Pseudophyllidea.(9) The first human infection by S. proliferum in the United States was reported in 1908.(14) Infection by S. proliferum has been reported in cats, dogs, and feral hogs, but this appears to be the first case of canine proliferative sparganosis in North America.(1-3,6)

The life cycle of S. proliferum has not yet been confirmed (12) but probably resembles that of other members of a related pseudophyllidian tapeworm, Spirometra spp. Adult tapeworms reside in the intestinal tract of a carnivorous definitive host, where they shed operculated eggs in the feces following discharge from the uterine pore of adult tapeworms. The operculated eggs then hatch in water, releasing a ciliated intermediate form (coracidium). The coracidium is ingested by the first intermediate host, a copepod crustacean (Cyclops sp.), where it develops into the procercoid stage. After the infected copepod is ingested by any one of a broad array of possible second intermediate hosts (any vertebrate other than a fish), the procercoids develop into plerocercoids (spargana) and migrate throughout the soft tissues of the body. If the second intermediate host is eaten by another non-fish vertebrate serving as a transport host, the plerocercoids migrate through the tissues but may remain as plerocercoids. The larval Spirometra can infect and survive in a series of transport hosts until finally consumed by a carnivore definitive host.(7) The ova are released from the uterine pore and are evident in the hosts feces 10-30 days after infection.(1,6,7,11) Infection of the dog can occur through three different ways: ingestion of contaminated water, direct infection of open wounds with plerocercoids, or ingestion of plerocercoids in intermediate vertebrate hosts (11,12) Due to its requirement for an aquatic primary intermediate host, clinical disease is usually associated with exposure to aquatic environments. Sparganosis is zoonotic; thus, precautions should be made to block human infection by preventing consumption of infected water and insufficiently cooked fish or game, or the application of infected medicinal poultices to wounds. It is interesting to note that the first human case of proliferative sparganosis in North America was reported in 1908 in a Florida resident living in the same geographic region as the current canine case.(14)

Currently, there are no products labeled for treatment of Spirometra spp infections.(7) The lack of treatment options for proliferative sparganosis warrants a poor prognosis for survival. Infection of dogs is best controlled by preventing the consumption of infected water or the ingestion of vertebrates that could serve as secondary intermediate hosts.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Adult cestodes are normally present in the intestine of the final host with larval forms present in tissue or body cavities of unfortunate intermediate hosts. Cestodes are split into segmented sections called proglottids that contain both female and male reproductive organs. Both larval and adult cestodes have suckers on their anterior end that may also have hooks depending on the species of cestode.(5)

Several types of cystic larval cestodes are often seen in tissue sections, and these include cysticercoids, cysticercus, coenurus, and the hydatid cyst. Cysticercoids are tiny larvae with a very small bladder and scolex that is encircled by parenchymous tissue. Cysticercus can be identified by a bladder with an inverted neck and scolex that always has four suckers. Coenurus is very similar in appearance to cysticercus but has more than one scolex. Hydatid cysts have a bladder with large numbers of very small scolices. (5)

In tissue section trematodes and cestodes look very similar, but to the trained eye they can be differentiated by a few key features. Both cestodes and trematodes are described as having a spongy parenchyma with no body cavity. Cestodes lack a digestive tract in contrast to trematodes which are endowed with one. Cestodes have calcareous corpuscles which are basophilic clear corpuscles of unknown function. Trematodes are devoid of calcareous corpuscles.(5) These features can help to delineate these two similar appearing parasites.Â

References:

97:239-242, 2001

2 Beveridge I, Friend SC, Jeganathan N, Charles J: Proliferative sparganosis in Australian dogs. Aust Vet J 76:757-759, 1998

3 Buergelt CD, Greiner EC, Senior DF: Proliferative sparganosis in a cat. J Parasitol 70:121-125, 1984

4 Chitwood M, Lichtenfels J: Parasitological Review: Identification of Parasitic Metazoa in Tissue Sections. Experimental Parasitology 32:407-519, 1972

5 Gardiner CH, Poynton SL: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, 1999

6 Gray ML, Rogers F, Little S, Puette M, Ambrose D, Hoberg EP: Sparganosis in feral hogs (Sus scrofa) from Florida. J Am Vet Med Assoc 215:204-208, 1999

7 Little S, D A: Spirometra Infection in Cats and Dogs. Compendium on continuing education for the practicing veterinarian 22:299-306, 2000

8 Mariaux J: A molecular phylogeny of the eucestoda. J Parasitol 84:114-124, 1998

9 Miyadera H, Kokaze A, Kuramochi T, Kita K, Machinami R, Noya O, Alarcon de Noya B, Okamoto M, Kojima S: Phylogenetic identification of sparganum proliferum as a pseudophyllidean cestode by the sequence analyses on mitcochondrial COI and nuclear sdhB genes. Parasitology International 50:93-104, 2001

10 Moulinier R, Martinez E, Torres J, Noya O, de NBA, Reyes O: Human proliferative sparganosis in Venezuela: report of a case. Am J Trop Med Hyg 31:358-363, 1982

11 Mueller JF: The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 60:3-14, 1974

12 Nakamura T, Hara M, Matsuoka M, Kawabata M, Tsuji M: Human proliferative sparganosis. A new Japanese case. Am J Clin Pathol 94:224-228, 1990

13 Noya O, Alarcon de Noya B, Arrechedera H, Torres J, Arguello C: Sparganum proliferum: an overview of its structure and ultrastructure. Int J Parasitol 22:631-640, 1992

14. Stiles W: The occurance of a proliferating cestode larva (sparganum proliferum) in a man in Florida. Bulletin of the Hygienic Laboratory 40:7-18, 1908