Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 10

November 29th, 2017

CASE I: H12/1754 (JPC 4019375).

Signalment: 3.5-year-old, Aberdeen

angus, Bos primigenius taurus, bovine.

History: Out of a group

of 6 animals, one cow showed chronic, profuse diarrhea and severe, progressive

emaciation. The bacteriologic investigation of the feces tested positive for

acid-fast rods and negative for Salmonella. Because of the suspicion of

paratuberculosis, the cow was euthanized and submitted for post-mortem

investigation.

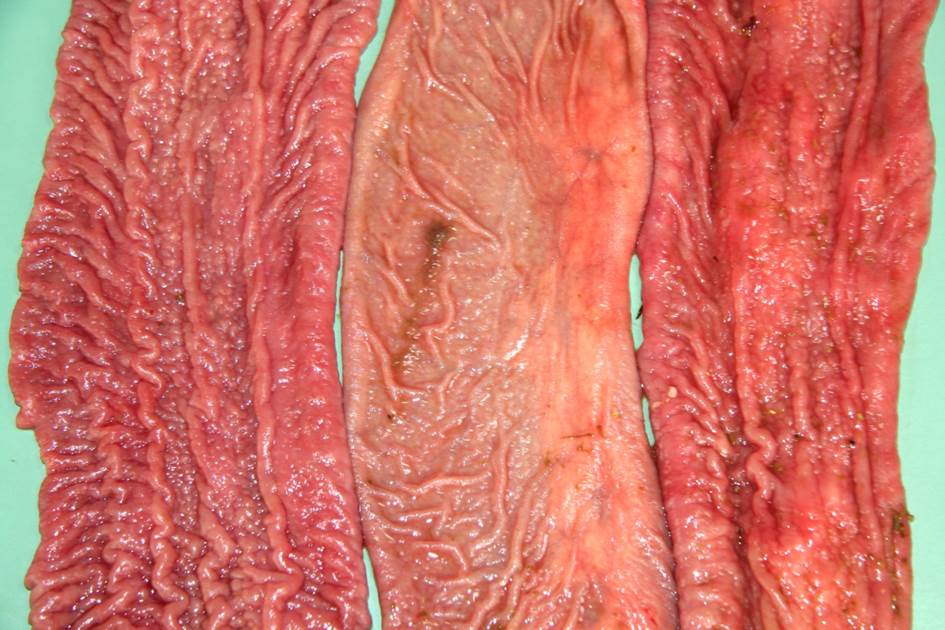

Gross Pathology: The animal was

moderately emaciated. The muscle masses were reduced, and the ribs were easily

palpated. Body fat depots were present. The mucosa of the small intestine, from

the duodenum to the ileum was moderate to severe thickened, corrugated, nodular

shaped and were light brown. The large intestine content was watery and brown,

becoming slightly mucoid in the rectum. No lesions in the colonic mucosa were

noted grossly. The mesenteric lymph nodes were moderately enlarged. The rumen

pH was 6.5, and the fibers of the content were up to 15 cm long.

Laboratory

results:

Blood parameters:

Hematology:

(changed parameters)

Banded Neutrophils 0.54

109/l 0 - 0.2

Segmented Neutrophils 6.25 109/l 1.0

- 3.5

Lymphocytes 2.05 109/l

2.5

- 5.5

Monocytes 0.93 109/l 0 - 0.33

Eosinophils 0.00 109/l 0.3 - 1.5

Chemistry:

(changed parameters)

Na 116 mmol/l 135

- 165

K 1.50 mmol/l 3.0

- 6.0

Cl 68 mmol/l 90

- 110

Urea 23.99 mmol/l 1.67

- 7.50

Creatinine 183 ?mol/l 88 -

133

Bilirubin 23.0 ?mol/l 0.85 - 8.6

ASAT (SGOT) 79 IU 117

- 234

GGT 67 IU 10

- 27

GLDH 46 IU 0 -

17

Serology Bovine viral diarrhea

(during Swiss eradication program): negative.

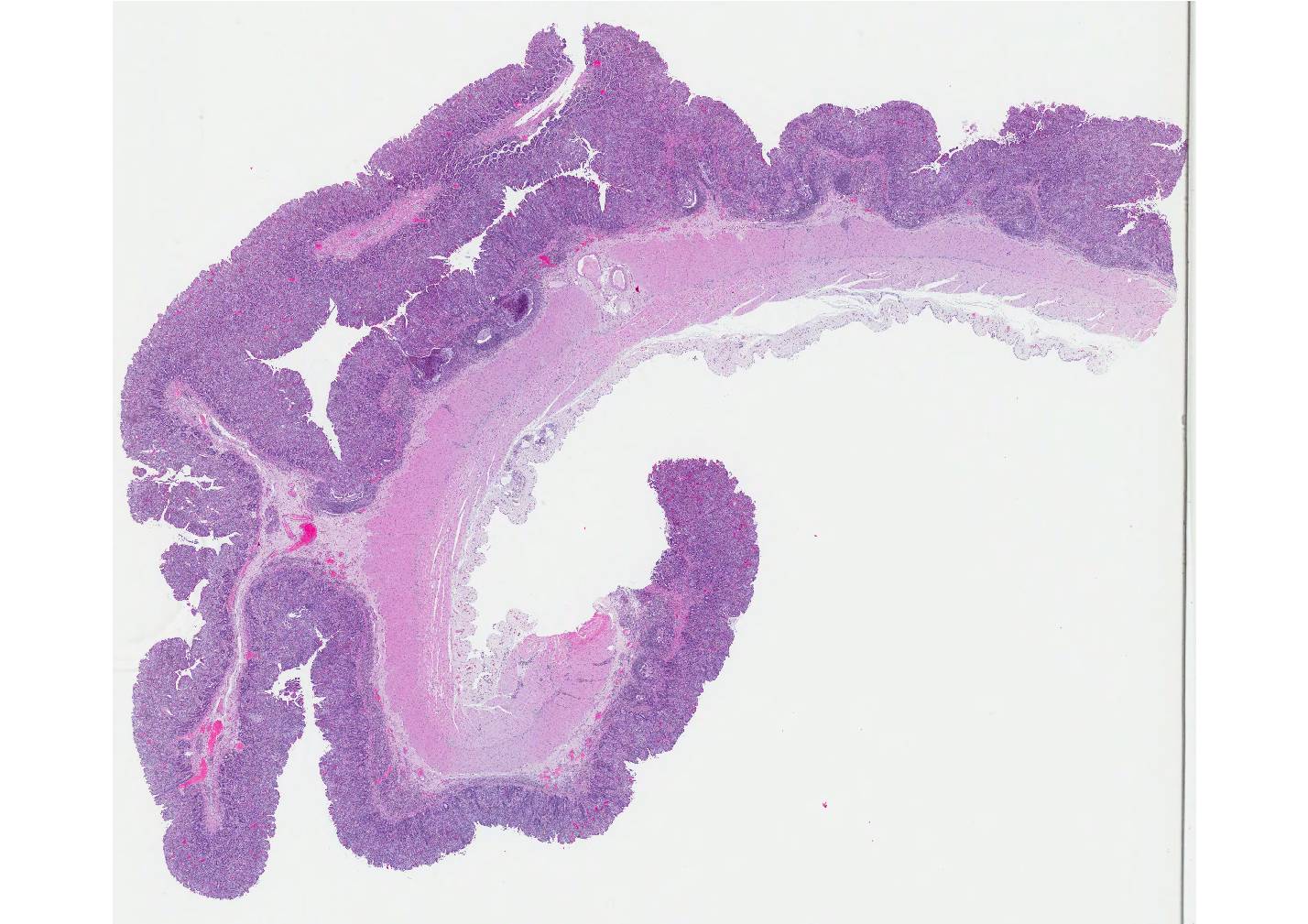

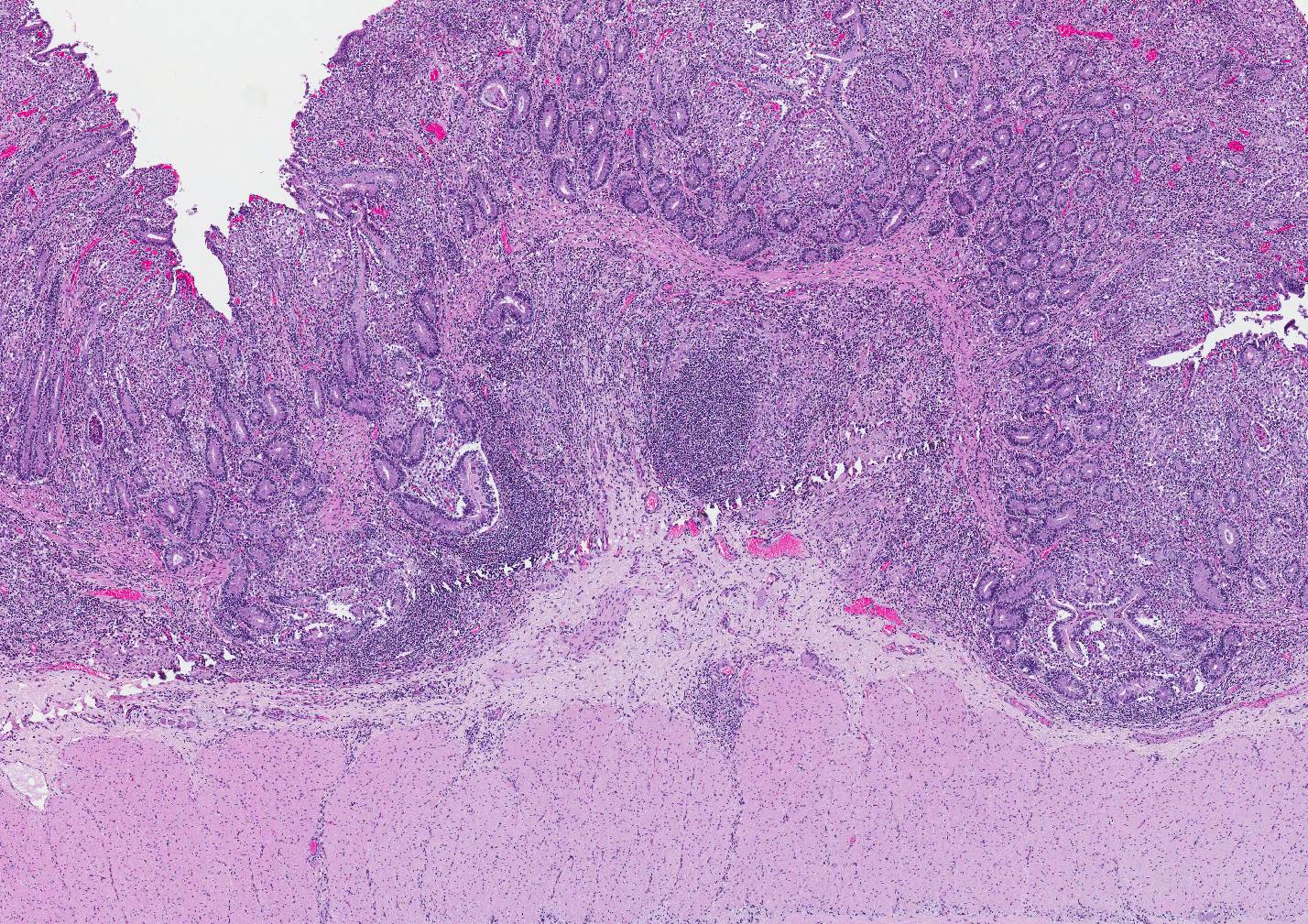

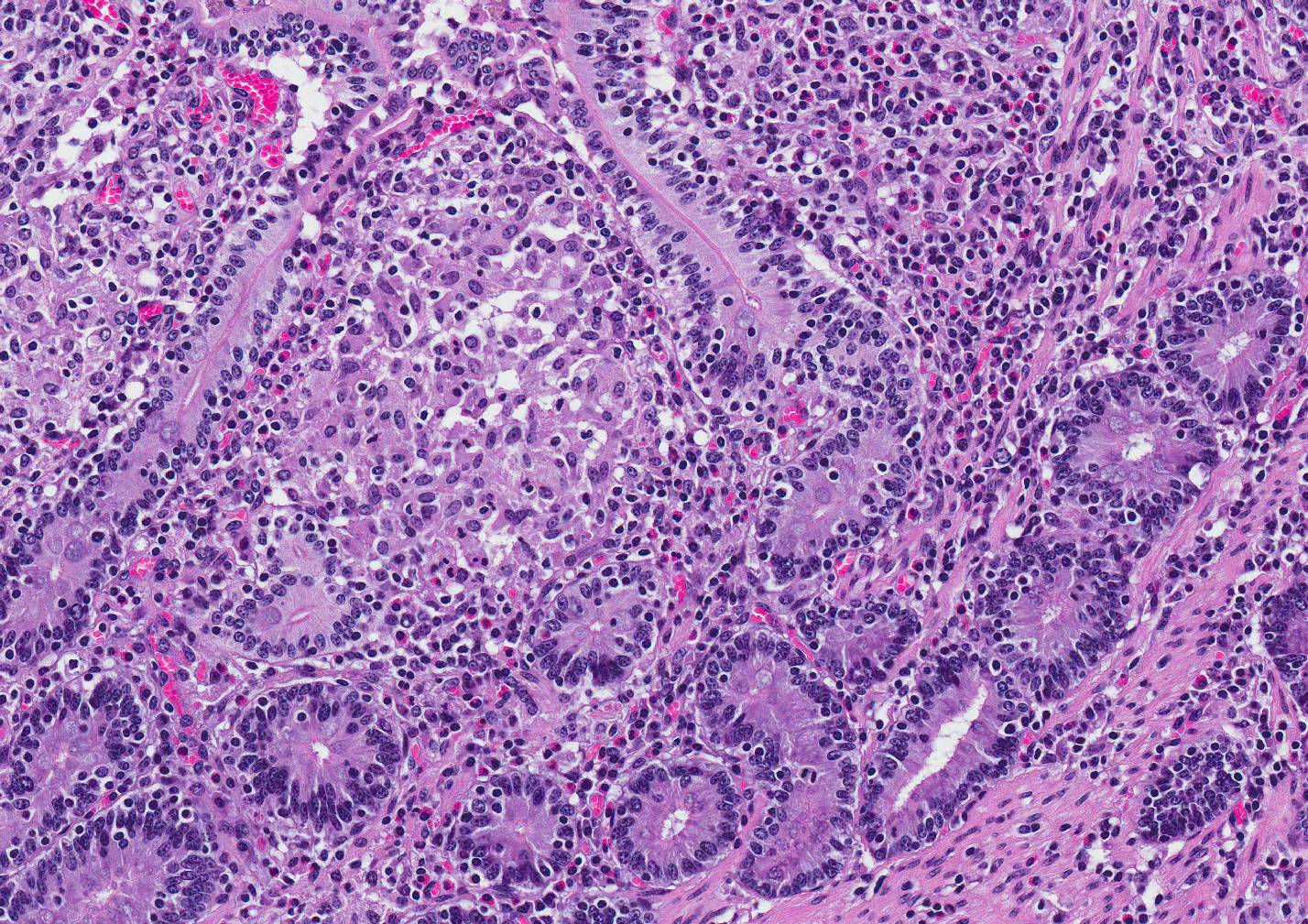

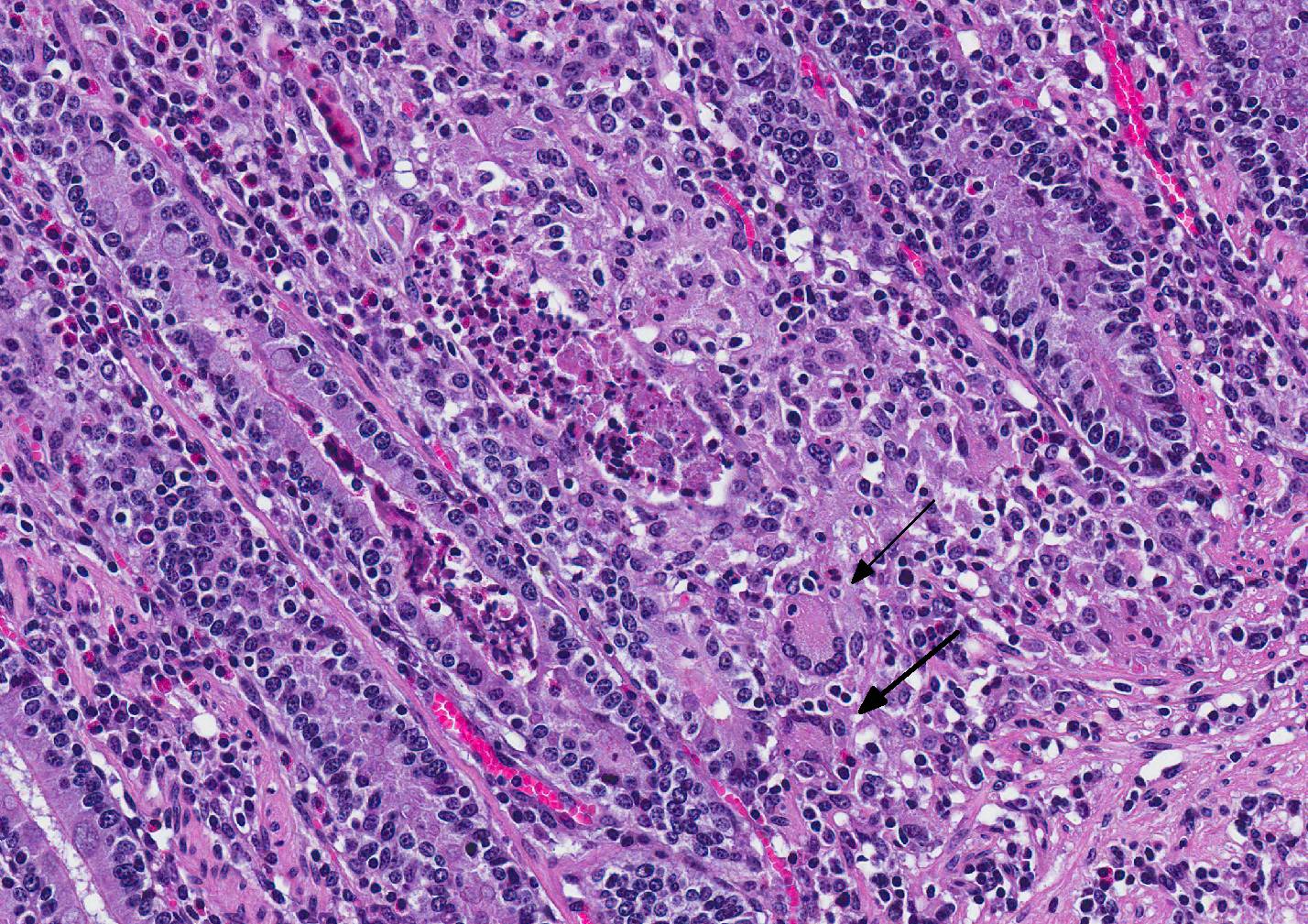

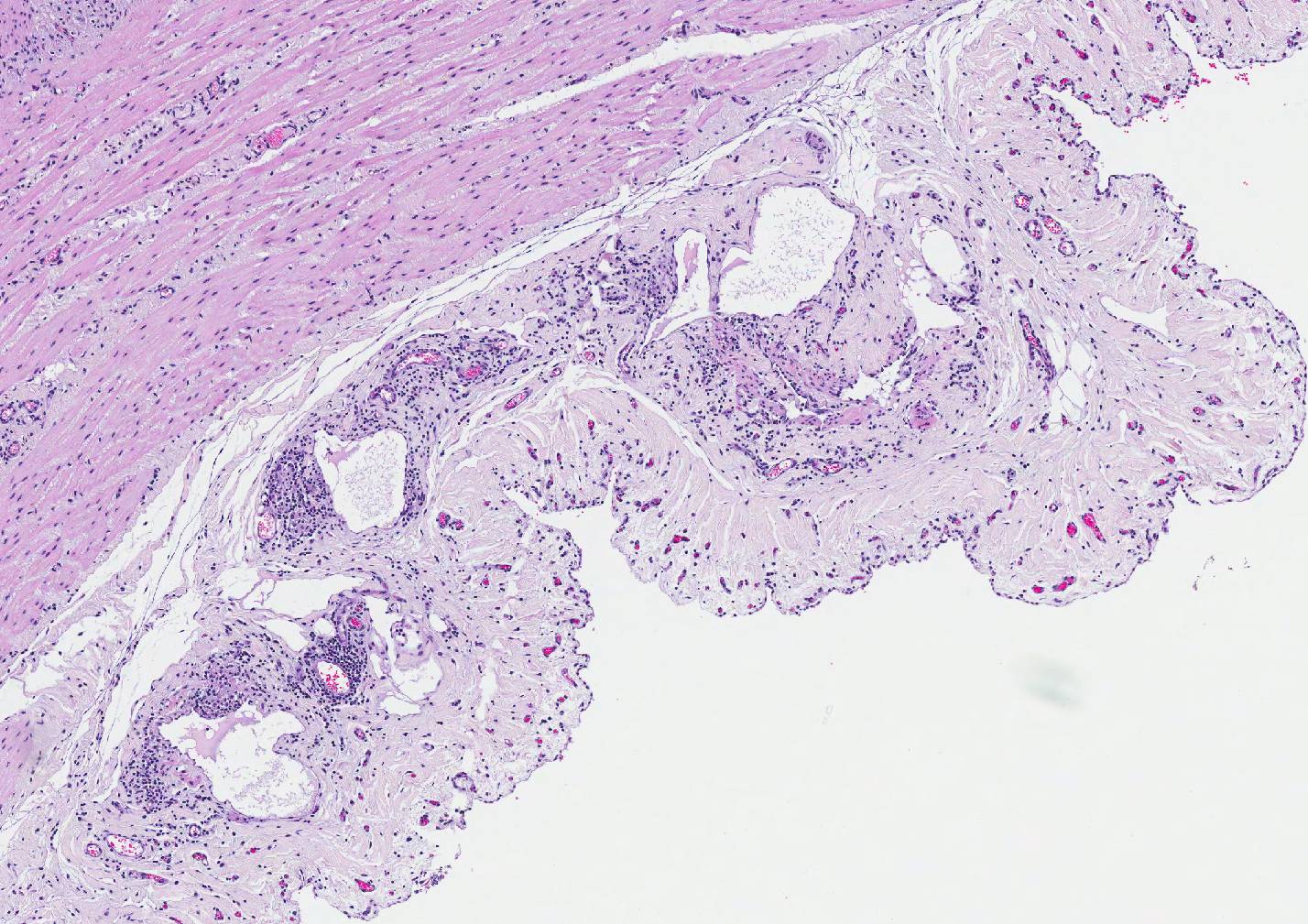

Microscopic Description: Small intestine: The intestine is thickened

and puts the mucosa in folds. About 90% of the lamina propria and the submucosa

are diffusely infiltrated by large numbers of epitheloid macrophages,

lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils and fewer neutrophils with numerous

multinucleated giant cells of the Langhans and foreign body type. The

infiltration distorts and expands the lamina propria of villi. Multifocally, the crypts are moderate to severe

extended, lined by an elongated and flattened epithelium. They contain

accumulations of cellular debris, mucous and crystalline material (dystrophic

calcification) (cryptitis). Crypt epithelium piles up with cells 3-5 deep and

with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (hyperplasia). The lamina propria, the

submucosa and the serosa are diffusely widened and pale (edema). The submucosal

and serosal lymphatics are diffusely moderately to severely dilated and

surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells and fewer macrophages. Rarely

epitheloid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells plug the lumen of the

lymphatics (lymphangitis).

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Granulomatous enteritis

and lymphangitis with multinucleated giant cells, diffuse, severe, chronic.

Contributors

Comment: Lesions extended from the duodenum to the colon. During necropsy we were

impressed about the classic lesion, as it is rarely seen in our necropsy room.

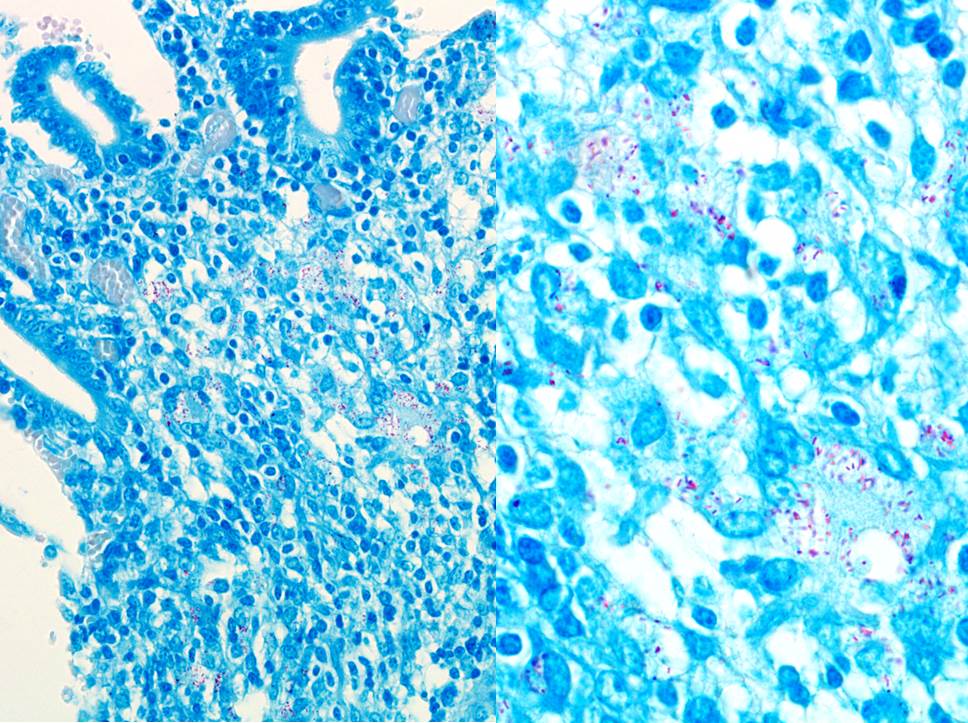

The classic histologic picture likewise was a treat. Ziehl-Neelson stained (ZN)

many acid-fast rods within the macrophages. The cow had a mild histiocytic

lymphadenitis of the mesenteric lymph nodes with ZN-positive rods as well. The

diagnosis is paratuberculosis or Johne"s disease. Although other infections can

be seen on top of mycobacteriosis (e.g. salmonellosis), further bacteriologic

investigation was not done.

Johne"s disease

(JD) or paratuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium (M.) avium subsp. paratuberculosis

(Map), causes chronic diarrhea in ruminants. As in our case, typical

gross lesions are thickened mucosa, thrown into transverse rugae which will not

disappear when the intestinal tract is stretched. Typical microscopic lesions

were granulomatous enteritis of the small intestine and lymphadenitis of the

draining lymph nodes.

The bacteria are

taken up orally by young animals. Susceptibility to infection is greatest in

the first 30 days of life. The incubation period of JD is protracted and

clinical symptoms are usually detected in cattle 2-5 years-old. Chronic villous

involvement leads to malabsorption, protein loss and profuse chronic diarrhea

and severe emaciation. The pathogenesis of JD is best understood in cattle. It

is assumed to be similar in other ruminants, except that in sheep and goats the

enteric gross lesions are often milder. Map

can be produced in pigs. Spontaneous disease occurs in a number of free-ranging

and captive wild ruminants, camelids, rarely in equines and captive primates.

Numerous species of wild mammals and several species of wild birds are

naturally infected, though not necessarily diseased.1

Map has been suspected to play a role

in Crohn"s disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory bowel disease in humans.

Initial suggestion of Map involvement was based on the similarity of the

clinical appearance of CD and JD. Map

has been detected in multiple CD studies, but it is difficult to isolate Map from patients with CD. Genetically,

over 30 Map genes have been identified in human disease, but no specific

association has been shown so far.

JD is used as a

bovine model of CD. Studies in cattle suggest the early immune response may be

similar to the immune response to M.

tuberculosis (Mtb) during the latent stage of infection. Map affords an opportunity to examine

the immune response during the early and late stages of infection. These data

would also provide insight into how mycobacterial pathogens could contribute to

the pathogenesis of CD.2

JPC

Diagnosis: Small

intestine: Enteritis, granulomatous and lymphocytic, diffuse, marked with

villar blunting, crypt abscessation and loss, and moderate lymphangitis, Aberdeen

angus (Bos primigenius Taurus),

bovine.

Conference

Comment: Johnes

disease in cattle, sheep, and goats is caused by Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis

(MAP) and induces granulomatous inflammation of the lepromatous (diffuse) type. The immune response is characterized by a Th2

type of adaptive immune response and appears microscopically as diffuse sheets

of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells rather than distinct granulomas

as would be expected with a Th1 response. Lesions are most common in the ileum,

colon, and mesenteric lymph nodes. Bacteria, which are often numerous, can be

identified within macrophages and extracellularly with acid-fast stains.

Johnes disease causes injury to cells in three ways: (1) lysis of epithelial

cells and extracellular matrix proteins that form cell junctional barriers in

the small intestinal mucosa, (2) dysfunction of afferent lymphatic drainage in

the small intestinal villi, and (3) lysis of monocyte-macrophage cells and

other cells within the lamina propria of infected intestinal villi from chronic

inflammatory mediators.3

Grossly, affected small intestinal walls

are thickened with a cerebriform appearance and mesenteric lymph nodes are

enlarged with coalescing areas of yellow-white caseous exudate which

occasionally mineralizes. Lymphangitis is common resulting in thickened cords

of lymphatic vessels coursing through the mesentery. Additionally, there is

marked muscle loss and wasting with intermandibular edema (attributable to

hypoproteinemia), fluid accumulation in body cavities, plaques of

mineralization and fibrosis within the tunica intima of the thoracic aorta, and

diffuse, watery diarrhea. Young animals are most susceptible, and are infected

through ingestion of the bacterium which binds to receptors on the luminal

surfaces of M (microfold) cells (which lack a mucous covering). Bacteria are then translocated across the

cell into the underlying Peyers patches and subsequently phagocytosed by

tissue macrophages. MAP requires iron for growth and secretes iron-chelating

proteins known as exochelins, iron-reductases, and siderophores as virulence

factors to acquire iron from ferritin stored in macrophages. Additionally,

mycobacterium species can: (1) inhibit acidification of the phagosome, fusion

of the phagosome and lysosome, and lysosomal enzyme activities through the

production of peroxidases; (2) block injury from reactive oxygen and nitrogen

intermediates; and (3) suppress macrophage activation by cytokines (IFN-?).3

There was apathetic debate amongst

conference attendees regarding the use of granulomatous versus

lymphoplasmacytic versus histiocytic to describe the inflammatory infiltrate in

this case, a debate which has been oft-repeated over the years, especially when

cases of Johnes disease are discussed.

In this particular case, the presence of multinucleated giant cells and epithelioid

macrophages suggest a granulomatous process, their presence however, was

restricted to the submucosa and further out, especially around lymphatics. Lymphocytes,

however, predominate in the lesion.

Ultimately, the group decided that the presence of numerous epithelioid

macrophages in the mucosa as well as the multinucleated macrophages warranted

the use of granulomatous in this particular instance.

Institute

of Animal Pathology, University of Berne

Länggassstrasse 122, Postfach 8466, CH-3001

Bern, Switzerland

http://www.itpa.vetsuisse.unibe.ch/htm

References:

1.

Brown

CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer"s Pathology of

Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier;

2007:222-225.

2.

Davis

WC, Madsen-Bouterse SA. Crohn"s disease and Mycobacterium avium subsp.

paratatuberculosis: The need for a study is long overdue. Vet. Immunol. Immpathol. 2012;145:1-6.

3.

Zachary

JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease.

6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017:162-163.