Signalment:

15-year-old, castrated male, mixed breed, (

Canis familiaris) dogA 15-year-old castrated male mongrel dog

developed a mass in the left hemimandible around

the first molar tooth. The owner reported that the dog

pawed at its mouth. Two 1 cm x 2 cm incisional biopsy

specimens from the buccal and lingual aspects of the mass

were processed en toto for histologic examination by a

reference laboratory; the diagnosis was osteosarcoma.

One month later, the dog was admitted to the Purdue

University Veterinary Teaching Hospital for total left

hemimandibulectomy.

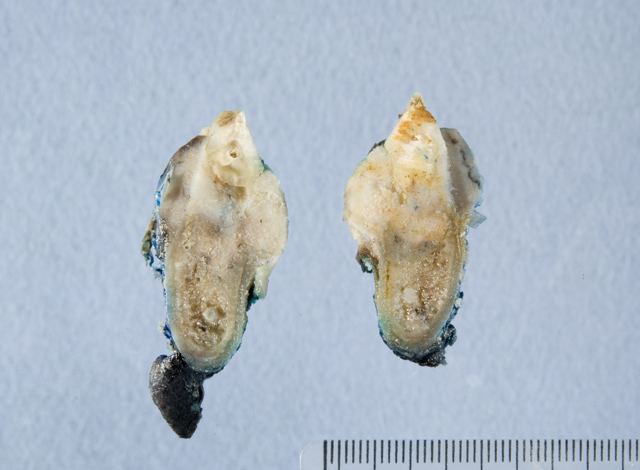

Gross Description:

A left hemimandibular surgical

specimen containing the entire mass had its margins painted

prior to immersion in 10% neutral buffered formalin and

submission to the Purdue University Animal Disease

Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL), where the specimen was

transferred to a formic acid decalcifying solution. A firm

to hard fibrous and bony mandibular mass surrounded

the neck and roots of the first molar tooth and measured

about 2.5 cm from rostral to caudal margins and 2 cm from

medial to lateral aspects (

Figs. 2-1, 2-2). The mass on

cross-section consisted mostly of hard, white tissue that

infiltrated alveolar and cortical bone and adjacent soft

tissue (

Fig. 2-3).

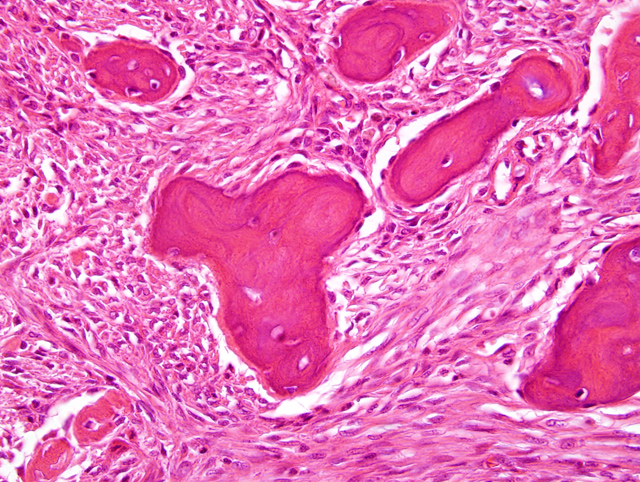

Histopathologic Description:

The tumor consisted

of a spindle-cell proliferation resembling periodontal

stroma that appeared to be centered midway between

the neck of the tooth and its apex. At its apparent site

of origin, the tumor had provoked osteoclastic destruction

of alveolar bone, adjacent cortical compacta, periodontal

ligament and bone of the alveolar crest. Symmetric

growth of the mass expanded the lingual and buccal

borders of the hemimandible, again by stimulating

osteoclastic removal of the cortical compacta at a rate

that allowed development of a thin, incomplete shell of

periosteal new bone that partially contained the tumor.

At the gingival sulcus, the incomplete and partially

resorbed periosteal shell of reactive bone nearly abutted

the junctional gingival epithelium. Upward expansion of

the tumor into gingival lamina propria led to ulceration

and granulation tissue formation. On the buccal surface,

the tumor was also partially bound by a thin periosteal

shell of reactive bone that ended at the former level of

the alveolar crest, which had been replaced by neoplastic

tissue. Here, the tumor extended above the level of the

periosteal reaction into the gingiva. Neoplastic tissue was

composed of fusiform cells in scanty fibrous stroma with

light but diffuse infiltration by neutrophils. The fusiform

cells had an elongated oval nucleus, small nucleolus, no

mitotic figures in 15 high-power fields, and scanty pale

eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct cell borders (

Fig.

2-5). The stroma was moderately vascular with numerous

irregular trabeculae of osteoid and partially mineralized

woven bone. Bony trabeculae were bordered by one layer

of osteoblasts. A few osteoclasts were adjacent to bony

spicules. There was little fibrous collagen in tumoral

stroma; most of the Massons trichrome-stained collagen

was in the bony trabeculae. A preliminary diagnosis of

ossifying fibroma was reported with the final diagnosis to

follow examination of remaining (central) tissue.

Sections of the fully decalcified central portion of the

tumor were histologically similar to the initial peripheral

sections, except that 1 to 3 mitotic figures were found per

ten high-power fields. Neoplastic tissue was not found in

soft tissue ventral to the hemimandible or in mandibular or

soft tissue caudal to the mass. Histologic impression was

complete excision of an ossifying fibroma.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mandibular ossifying fibroma

Lab Results:

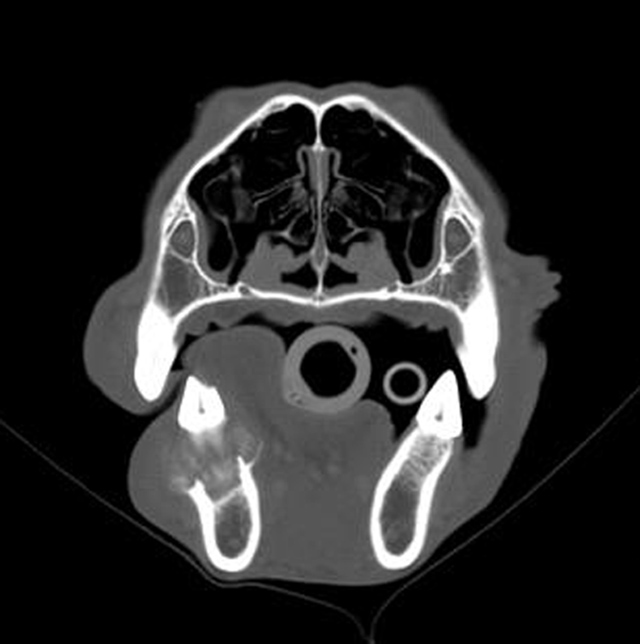

No abnormalities were detected in

the available lateral radiographic view of the skull because

of superimposition of the hemimandibles. However, in

the computed tomographic (CT) scan, an expansile and

lytic lesion, about 1.8 cm in width and 2 cm from rostral to

caudal borders, was evident in the dorsal aspect of the left

hemimandible, surrounding the neck and roots of the first

molar tooth (

Fig. 2-4). The mass destroyed alveolar and

cortical bone, but had well-defined borders with a short

transition zone. There was slight swelling, but no postcontrast

enhancement of adjacent soft tissues. Thoracic

and abdominal radiographs were within normal limits and

free of evidence of metastatic neoplasia.

Condition:

Ossifying fibroma

Contributor Comment:

The case was reported as a

brief communication in Vet Pathol.

1 Benign fibro-osseous

proliferations of bone in veterinary species include

ossifying fibroma, osteoma, and fibrous dysplasia.

2,3

Osteomas are typically solitary osteosclerotic lesions

that arise from the surface of bones of the jaw or skull;

trabeculae of woven bone constitute the bulk of the tumor,

are rimmed by one layer of well-differentiated osteoblasts

and, in many cases, are oriented perpendicular to the

surface of the tumor.

3 Fibrous dysplasia

3 is a tumorlike

lesion that can involve one or multiple bones, often

in young animals. It arises within the bone, rather than

from the periosteal surface, and its ample fibrous stroma

contains only thin, curved trabeculae of woven bone. The

bony trabeculae are generally not rimmed by osteoblasts,

which distinguishes it from ossifying fibroma or osteoma,

and are regularly spaced but without orientation relative to

the periosteal surface.

Ossifying fibroma has histologic features that are

intermediate between those of osteoma and fibrous

dysplasia, although there can be overlap among the three

entities.

2 Ossifying fibroma is an expansile, lytic, and

invasive mass that develops within the bone, particularly

the mandible. Its bony trabeculae are rimmed by

osteoblasts as in osteoma, but are arranged haphazardly

and contribute relatively less to the fibro-osseous stroma.

Importantly, from a prognostic perspective, ossifying

fibroma must be differentiated from malignant tumors,

such as osteosarcoma. That distinction can be based on

the lower cellularity, bland cytologic features, and low

mitotic index of ossifying fibroma. Furthermore, bony

trabeculae of ossifying fibroma tend to be better developed

than in osteosarcoma and are bordered by a single layer of

osteoblasts that are distinct from the tumor cells. However,

histologic examination of excisional biopsy specimens

and knowledge of the anatomic location of the tumor may

be necessary for accurate diagnosis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Gingiva, tooth, and alveolar and

cortical bone: Ossifying fibroma

Conference Comment:

Ossifying fibromas are

most commonly reported in young horses, generally less

than one year of age, and usually present as a protruding

mass from the rostral mandible.

4 There have also been

reported cases in cats, dogs, and sheep.

4 In horses, the

differential diagnosis for ossifying fibroma includes

fibrous osteodystrophy, fibrous dysplasia, osteoma, and

osteosarcoma.

4 Fibrous osteodystrophy presents as a

symmetrical, bilateral lesion with numerous osteoclasts.

4

In fibrous dysplasia, bone spicules are not rimmed by

osteoblasts and are more uniform.

4 Osteomas are composed

of more normal appearing bone, while osteosarcomas have

invasive, pleomorphic cells with a higher mitotic index.

4

Osteomas are most common in horses and cattle and have

been reported as large as 14 cm in diameter.

3

Many tumors diagnosed as osteomas in dogs are actually

multilobular tumors of bone.

3 Histologically, the multilobular

tumor of bone consists of multiple vari-shaped

nodules of bone and/or cartilage at various stages of

differentiation separated by a fibrovascular stroma.

2,4

These tumors are slow growing but can be invasive and

may metastasize.

4 They have been reported in dogs,

cats, and horses.

4 Osteomas are dense masses of welldifferentiated

bone that protrude from bone surfaces.

References:

1. Miller MA, Towle HAM, Heng HG, Greenberg CB,

Pool RR: Mandibular ossifying fibroma in a dog. Vet

Pathol

45:203-206, 2008

2. Slayter MV, Boosinger TR, Pool RR, D+�-�mmrich K,

Misdorp W, Larsen S: Benign tumors.Â

In: Histological

Classification of Bone and Joint Tumors of Domestic

Animals, 2nd series, vol. 1, p. 5-7. Armed Forces Institute

of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1994

3. Thomson KG, Pool RR: Benign tumors of bone.Â

In:

Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp.

248-255. Iowa State Press, Ames, IA, 2002

4. Thompson K: Bones and joints.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy

and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, vol 1 ed.

Maxie MG, 5th ed., pp.110-124. Elsevier, Philadelphia,

PA, 2007