WSC 2023-2024, Conference 18, Case 1

Signalment:

Adult female American bison (Bison bison)

History:

Owner reports weight loss and sporadic loss of animals of all ages for the past year.

Gross Pathology:

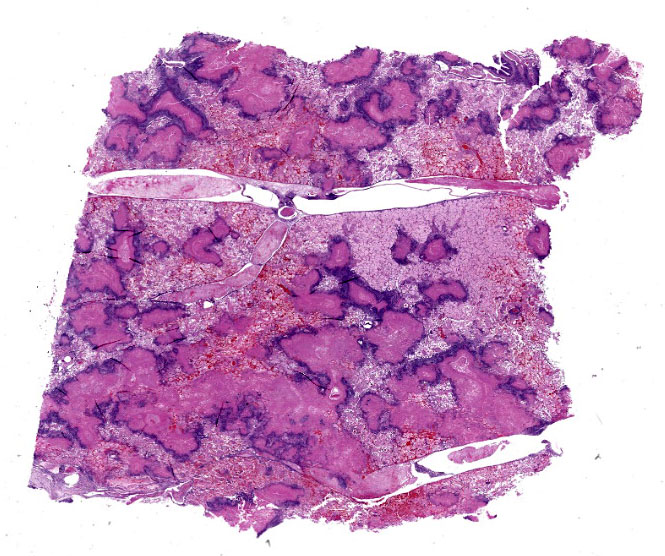

The pleural surface is covered in a thick mat of fibrin. On cut section, there are multifocal 0.1-1.0 cm diameter abscesses containing caseonecrotic exudate.

Laboratory Results:

Aerobic culture: No growth.

PCR for BHV-1, BRSV, BVDV, PI3: Undetected.

PCR for Histophilus somni: Undetected.

PCR for Mycoplasma bovis: Undetected.

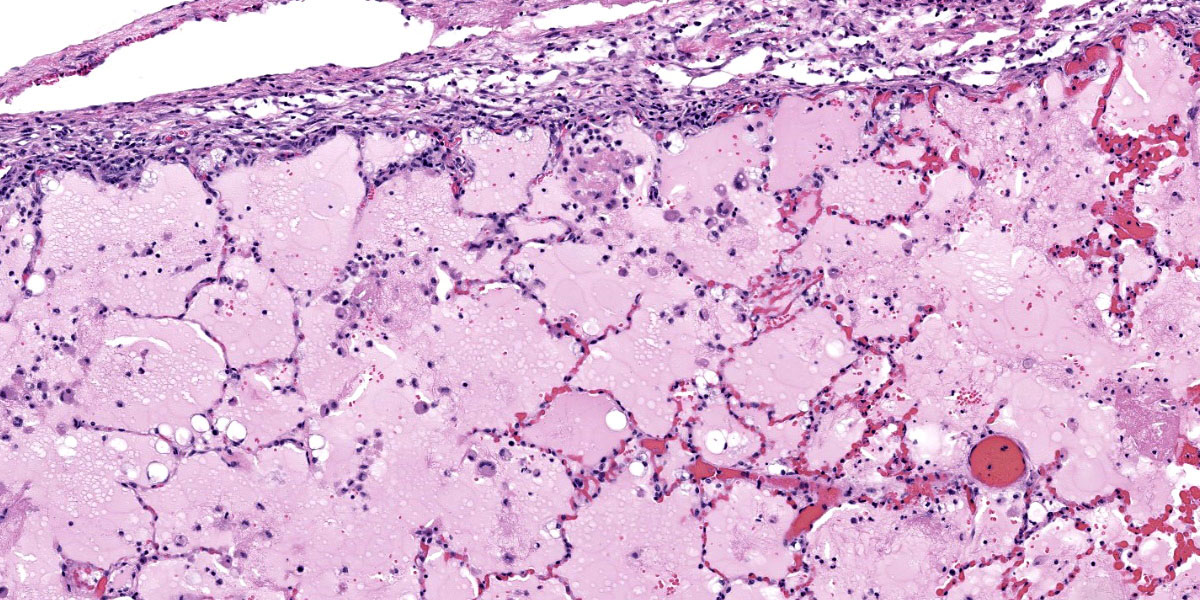

Microscopic Description:

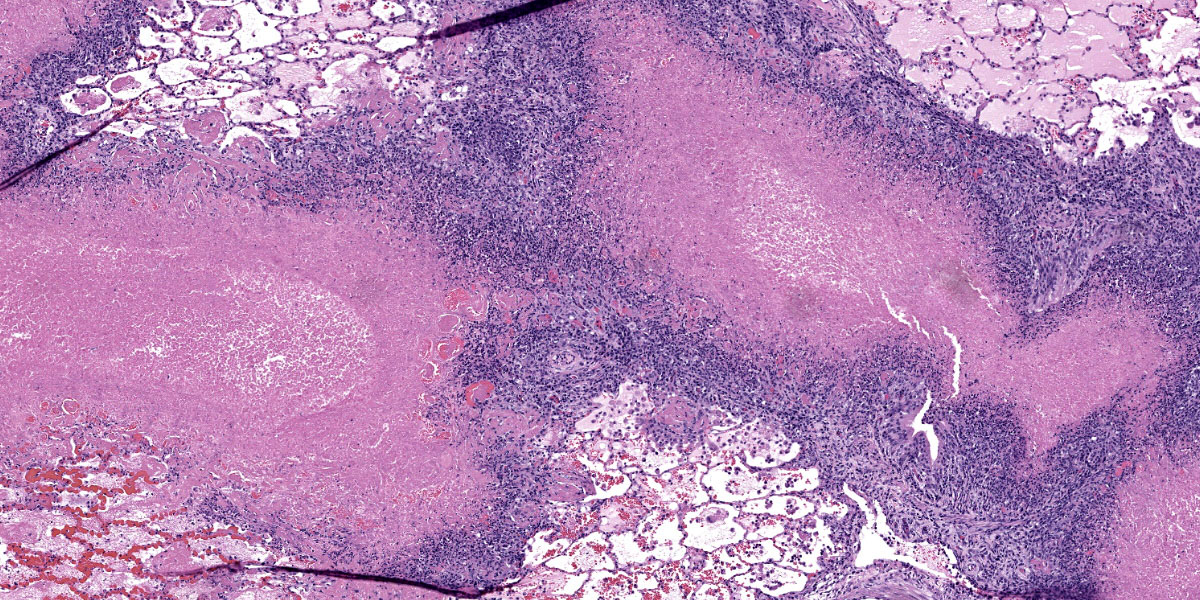

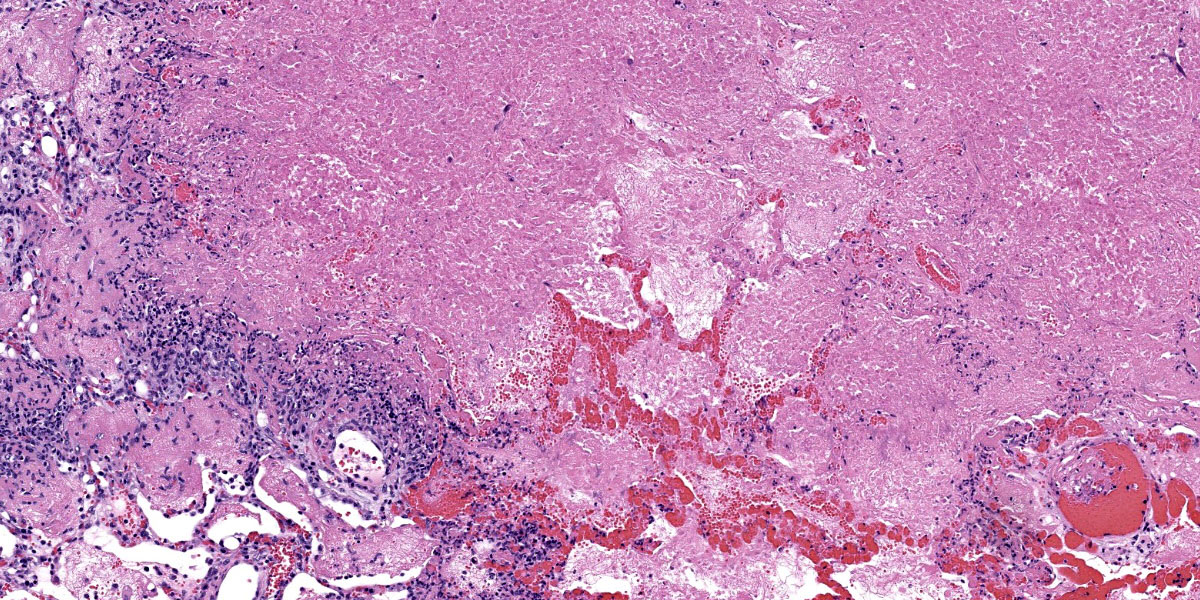

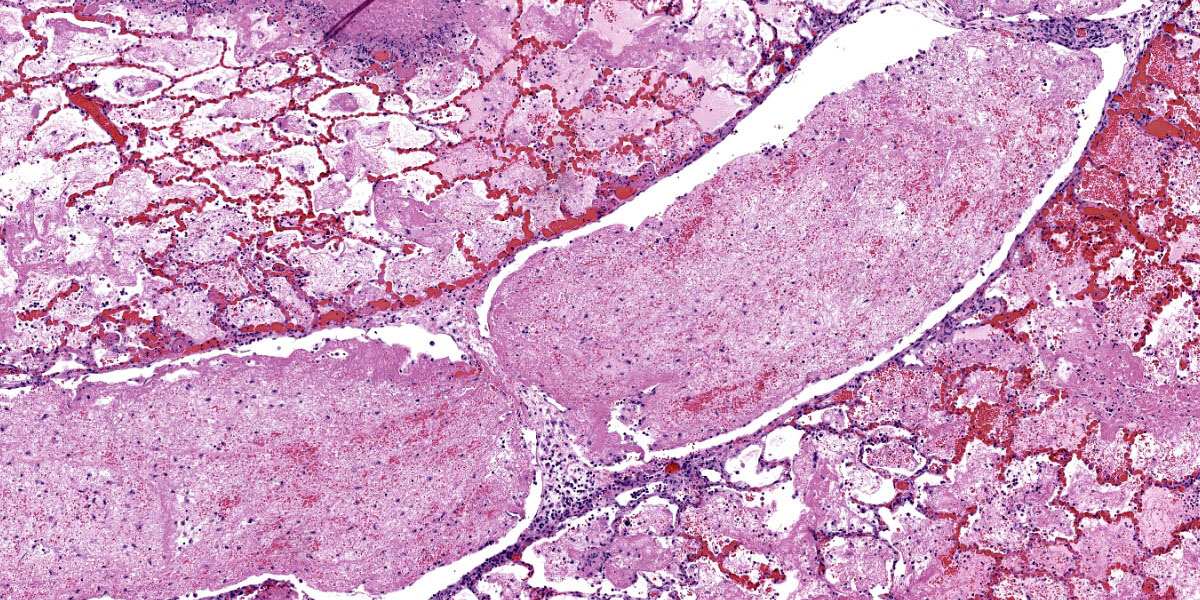

Throughout the section there is multifocal to coalescing necrosis affecting >50% of the lung tissue. Necrotic foci efface bronchioles and are characterized by a hypereosinophilic core surrounded by a peripheral rim of degenerate neutrophils admixed with pyknotic to karyorrhectic debris. There is central mineralization in some necrotic foci. In the adjacent alveoli, there is frequent necrosis of septa with abundant hyalinized material and/or flooding of remnant alveolar spaces by edema, fibrin,

hemorrhage, and many foamy macrophages. Large bronchi have mildly hyperplastic epithelium. Some vessels are occluded by hyalinized fibrin thrombi.

Immunohistochemistry: There is positive immunoreactivity for Mycoplasma bovis in the previously described lesions, particularly at the edges of necrotic foci. The lung is diffusely negative for Histophilus somni immunoreactivity.

Special stains: No organisms were detected with acid-fast and modified acid-fast stains.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Bronchopneumonia, severe, diffuse, subacute to chronic, necrosuppurative, with caseonecrotic abscesses and fibrinous pleuritis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Mycoplasma is a genus of ubiquitous bacteria that consists of over 100 described species. The organisms are anaerobic, self-replicating, and lack a cell wall. Tissue tropism and host specificity vary between Mycoplasma species, and the manner in which infection leads to disease is not well understood.

Mycoplasma bovis is a globally distributed, economically important bacterial pathogen that contributes to the bovine respiratory disease complex.4 In addition to pneumonia, M. bovis can cause mastitis, polyarthritis, otitis media, keratoconjuncitivitis, and reproductive losses in cattle.11 Historically, M. bovis was rarely detected in other species. In the early 2000’s, however, M. bovis was documented as the cause of several high morbidity and mortality disease outbreaks in American bison.19 The emergence of mycoplasmosis in bison has resulted in devastating economic loss to the commercial bison industry and continues to threaten bison production operations throughout North America.1,5,6,9,18

Since the initial emergence, numerous clinical manifestations of mycoplasmosis have been dscribed in bison. These include pneumonia, necrotic pharyngitis, polyarthritis, reproductive disorders, and systemic disease.5,6,9,18 In contrast to cattle in which co-infecting pathogens are common, there is evidence that M. bovis acts as a primary pathogen in bison with increased virulence and higher case fatality rates.9,11,15,19

Control of M. bovis has been challenging.3 Efforts to protect bison via autogenous vaccines have been met with difficulty due to the remarkable evolutionary capacity of the bacterium.1,8,12 Treatment is limited due to the absence of a cell wall and associated resistance to many commonly used antibiotics.4,11 Further, a recent study documented that approximately 3% of bison are asymptomatic carriers of M. bovis.14 Chronic carriers can be difficult to identify and detect, complicating herd assessment and management strategies.16,17

Recently, M. bovis was detected as the cause of a high mortality outbreak in free-rangingpronghorn (Antilocapra americana) in Wyoming.10 Mule deer and white-tailed deer are also susceptible to M. bovis, meriting concern for impacts to wildlife, including n-commercial bison.7,13

Contributing Institution:

University of Wyoming

Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory

Department of Veterinary Sciences

https://www.uwyo.edu/vetsci/

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Bronchopneumonia, necrotizing and fibrinosuppurative, diffuse, severe, with fibrinous pleuritis and bronchiectasis.

JPC Comment:

The rugged American bison is emblematic of the untamed American West and, as of 2016, serves as the national mammal of the United States. Once hunted to near extinction, decades of conservation efforts have restored buffalo numbers to healthy levels in the Western United States and Canada. The emergence of Mycoplasma bovis in American bison herds in the last few decades has therefore been met with alarm, particularly due to the severity of disease in this species compared to cattle, and, as the contributor notes, the lack of effective vaccines against or treatments for this wily bacterium.

Despite being a well-documented member of the bovine respiratory disease complex, the molecular mechanisms that underly the virulence and pathogenicity of M. bovis remain incompletely understood.2 A key contributor to the bacterium’s host immune system evasion is a fairly complex system of antigenic variation. This variation is accomplished via several prominent, interchangeable transmembrane proteins that act as major immunogens and are switched out when effective host antibodies are encountered.2 These proteins belong to a family of 13 variable membrane surface lipoproteins (Vsps), encoded by 13 corresponding genes, only two of which are expressed at any one time.2 These Vsps can be expressed in different combinations, and their co-expression creates “M. bovis surface mosaics” that each have different antigenic properties.2 Additional antigenic variability can be introduced through insertions and deletions in sequence repeats within these genes, resulting in the production of differently sized protein variants, presumably with different antigenic properties, from a limited number of Vsp genes. Variation in Vsp expression and size has been demonstrated among individual bacterial subpopulations in affected animals, and this subpopulation diversity thwarts the host’s immune system and contributes to the chronic, intractable nature of disease caused by M. bovis.2

M. bovis, like all mycoplasma species, is a streamlined organism with a small genome, no cell wall, and a lifestyle that depends heavily on host cells for life-sustaining nutrients and cellular processes. This co-dependence requires close association between the bacterium and host cells; however, little is definitively known about how M. bovis adheres to and survives inside host cells. The previously discussed Vsps are thought to also facilitate host cell adhesion, though the variability in surface antigens, so useful in immune system evasion, can lead to more or less successful adhesion depending on the efficacy of the expressed bacterial ligands.2 A bacterial subpopulation’s particular Vsp complement can also enhance or degrade its ability to form biofilms, likely a critical component of bacterial persisteance. M. bovis is also able to survive intracellulary within phagosomes and to modulate host immune responses by inducing apoptosis of host T lymphocytes, among other immunomodulatory actions; however, the mechanisms behind these antics have not been fully elucidated. The end result of all of this bacterial subterfuge is chronic infection, and the hallmark of M. bovis disease in bison is an initially promising response to antibiotic therapy followed by repeated relapses, wasting, and eventual death or human euthanasia.19

This week’s conference was moderated by LTC Chris Schellhase, Chief of Diagnostic Services at the Joint Pathology Center, who began discussion by noting the massive amount of fibrin, edema, and necrosis appreciable on subgross evaluation. Some participants were intrigued by the multifocal vasculitis present throughout the section and wondered if the vasculitis was a primary lesion, which would be unusual with M. bovis infection, or if the vessels were simply bystanders being taken along for a very inflammatory ride. Conference participants also discussed whether some of the large fibrin aggregates, such as those within the interlobular septa, were present within blood or lymphatic vessels. Participants noted the large, dilated bronchi which were multifocally effaced by inflammatory cells, fibrin, and edema and felt that these changes likely represent bronchiectasis, a common finding in Mycoplasma pneumonias generally. Finally, participants reviewed special stains, including a Fite-Faraco, which unexpectedly contained many acid fast bacteria. The significance of this finding is unclear.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis revisited the vasculitis debate. Participants felt that the vasculitis was likely a bystander rather than a primary process and it was, for this reason, omitted from the final morphologic diagnosis.

References:

- Bras AL, Barkema HW, Woodbury MR, Ribble CS, Perez-Casal J, Windeyer MC. Clinical presentation, prevalence, and risk factors associated with Mycoplasma bovis-associated disease in farmed bison (Bison bison) herds in western Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;250(10):1167-1175.

- Burki S, Frey J, Pilo P. Virulence, persistence and dissemination of Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Microbiol. 2015;179(1-2):15-22.

- Calcutt MJ, Lysnyansky I, Sachse K, Fox LK, Nicholas RAJ, Ayling RD. Gap analysis of Mycoplasma bovis disease, diagnosis and control: An aid to identify future development requirements. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65 Suppl 1:91-109.

- Caswell JL, Archambault M. Mycoplasma bovis pneumonia in cattle. Anim Health Res Rev. 2007;8(2):161-186.

- Dyer N, Hansen-Lardy L, Krogh D, Schaan L, Schamber E. An outbreak of chronic pneumonia and polyarthritis syndrome caused by Mycoplasma bovis in feedlot bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20(3):369-371.

- Dyer N, Register KB, Miskimins D, Newell T. Necrotic pharyngitis associated with Mycoplasma bovis infections in American bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013;25(2):301-303.

- Dyer NW, Krogh DF, Schaan LP. Pulmonary mycoplasmosis in farmed white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Wildl Dis. 2004;40(2):366-370.

- Kumar R, Register K, Christopher-Hennings J, et al. Population genomic analysis of Mycoplasma bovis elucidates geographical variations and genes associated with host-types. Microorganisms. 2020;8 (10):1561.

- Kyathanahalli S. Janardhan MH, Neil Dyer, Richard D. Oberst, Brad M. DeBey. Mycoplasma bovis outbreak in a herd of North American bison (Bison bison). J Vet

- Malmberg JL, O’Toole D, Creekmore T, et al. Mycoplasma bovis Infections in Free-Ranging Pronghorn, Wyoming, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10): 2807-2814.

- Maunsell FP, Woolums AR, Francoz D, et al. Mycoplasma bovis infections in cattle. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25: 772-783.

- Perez-Casal J, Prysliak T, Maina T, Suleman M, Jimbo S. Status of the development of a vaccine against Mycoplasma bovis. Vaccine. 2017;35(22):2902-2907.

- Register KB, Jelinski MD, Waldner M, et al. Comparison of multilocus sequence types found among North American isolates of Mycoplasma bovis from cattle, bison, and deer, 2007-2017. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019;31(6):899-904.

- Register KB, Jones LC, Boatwright WD, et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma spp. in the Respiratory Tract of Healthy North American Bison (Bison bison) and Comparison with Serum Antibody Status. J Wildlife Dis. 2021;57(3):683-688.

- Register KB, Olsen SC, Sacco RE, et al. Relative virulence in bison and cattle of bison-associated genotypes of Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Microbiol. 2018;222:55-63.

- Register KB, Parker M, Patyk KA, et al. Serological evidence for historical and present-day exposure of North American bison to Mycoplasma bovis. BMC Vet Res. 2021;17(1):1-10.

- Register KB, Sacco RE, Olsen SC. Evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detection of Mycoplasma bovis-specific antibody in bison sera. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20(9):1405-1409.

- Register KB, Woodbury MR, Davies JL, et al. Systemic mycoplasmosis with dystocia and abortion in a North American bison (Bison bison) herd. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013;25(4):541-545.

- Sweeney S, Jones R, Patyk K, LoSapio C. Mycoplasma bovis-an emerging pathogen in ranched bison. 2013. Available at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/bison/downloads/bison14/