Signalment:

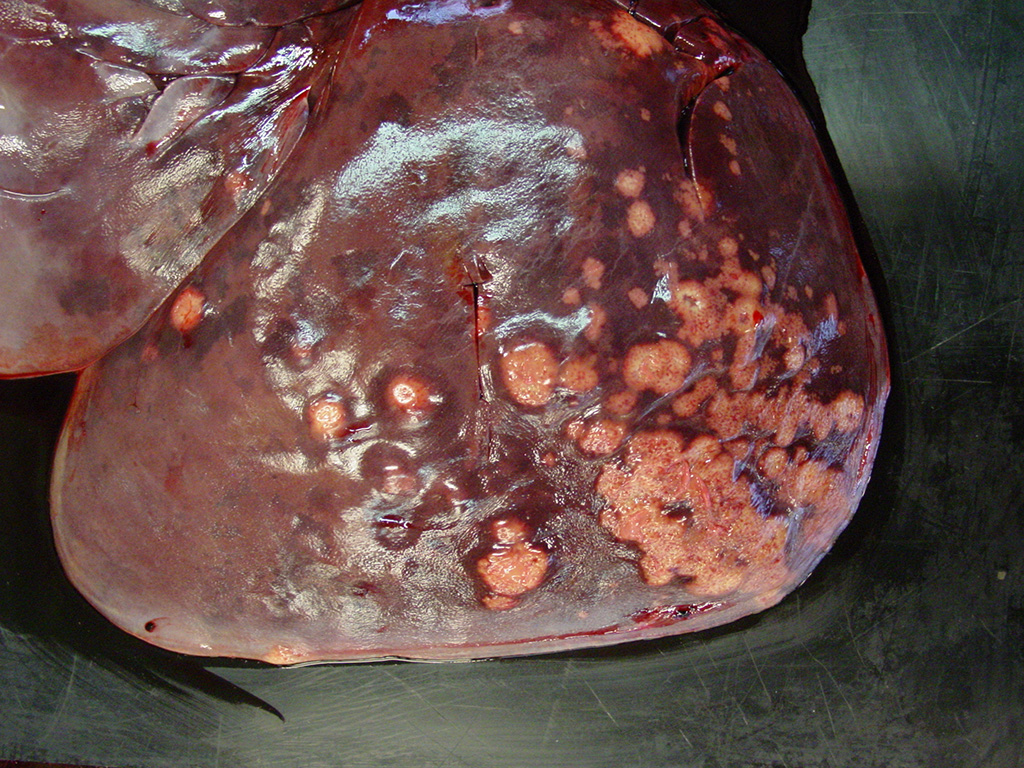

Gross Description:

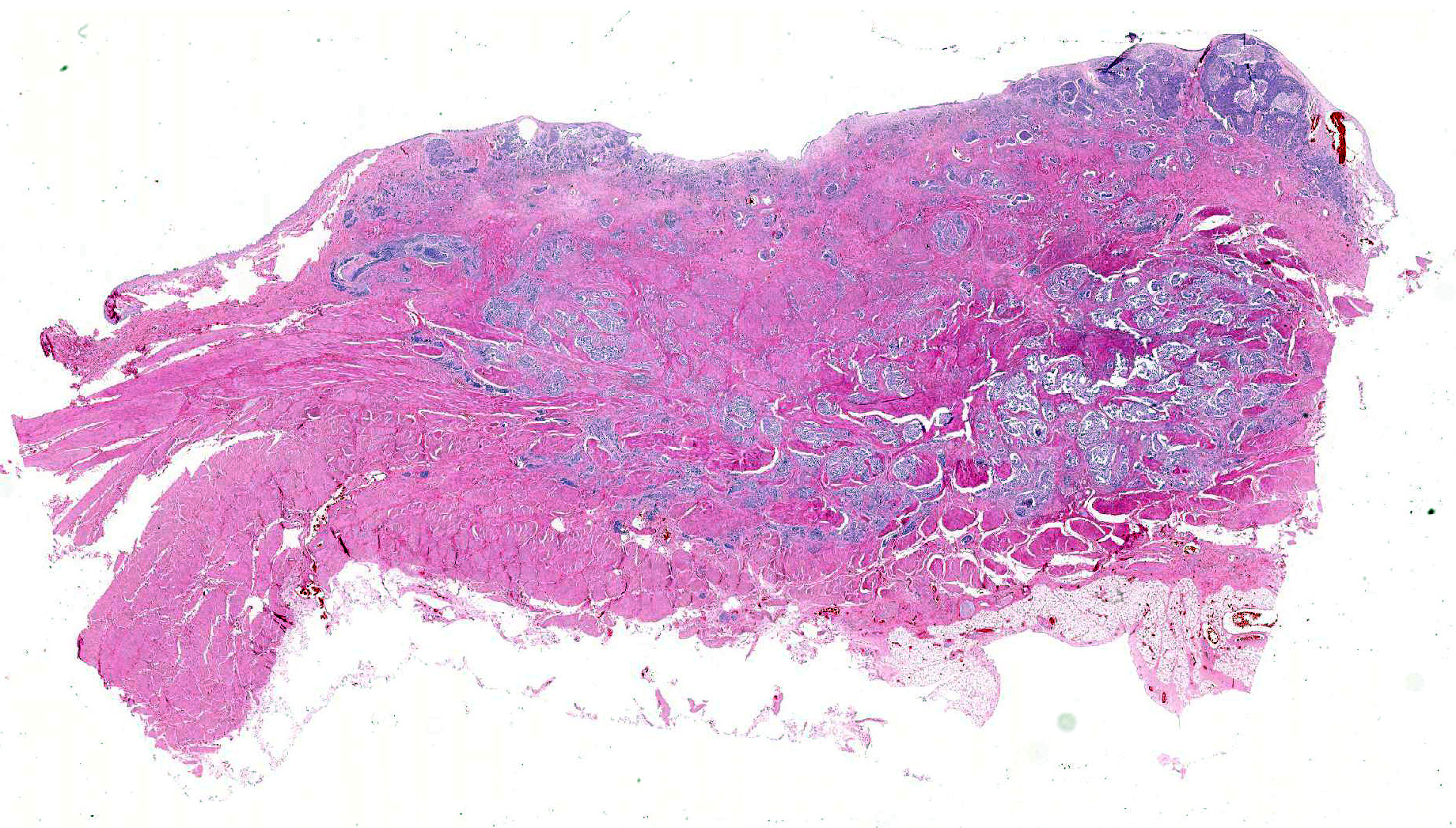

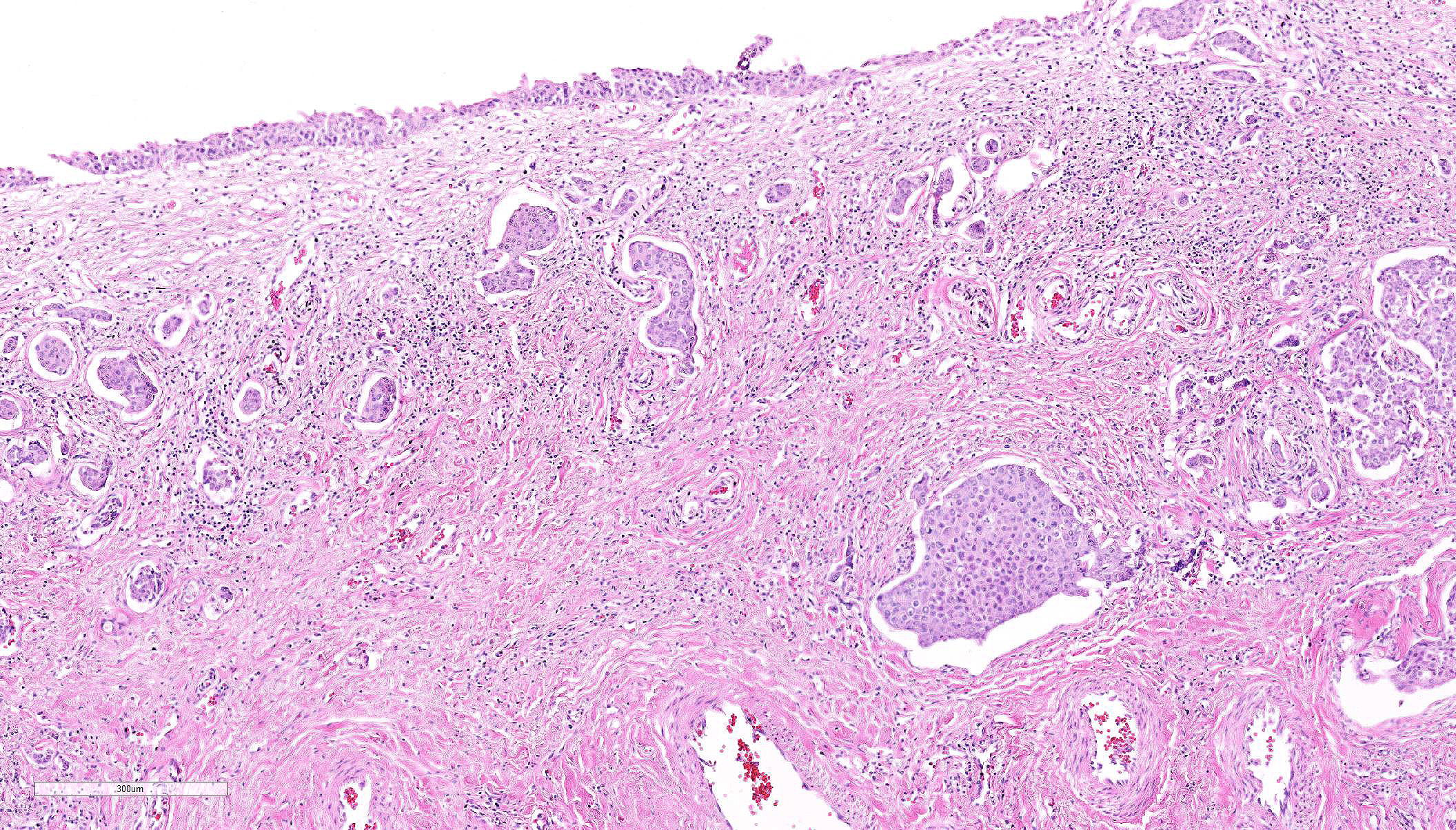

Histopathologic Description:

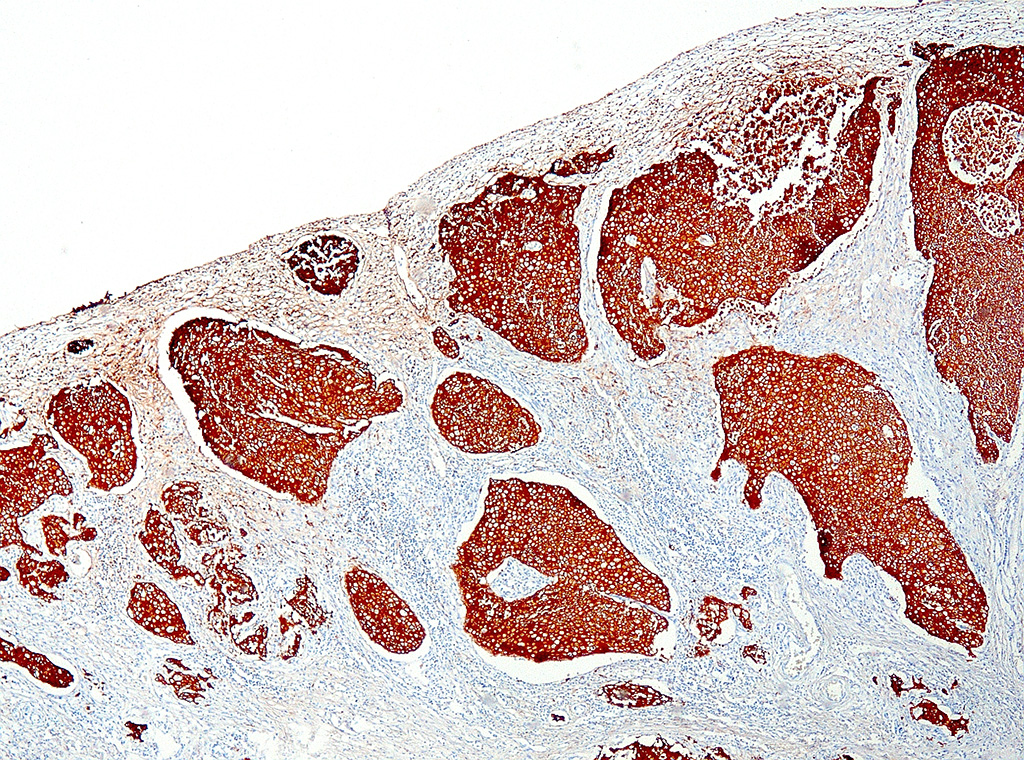

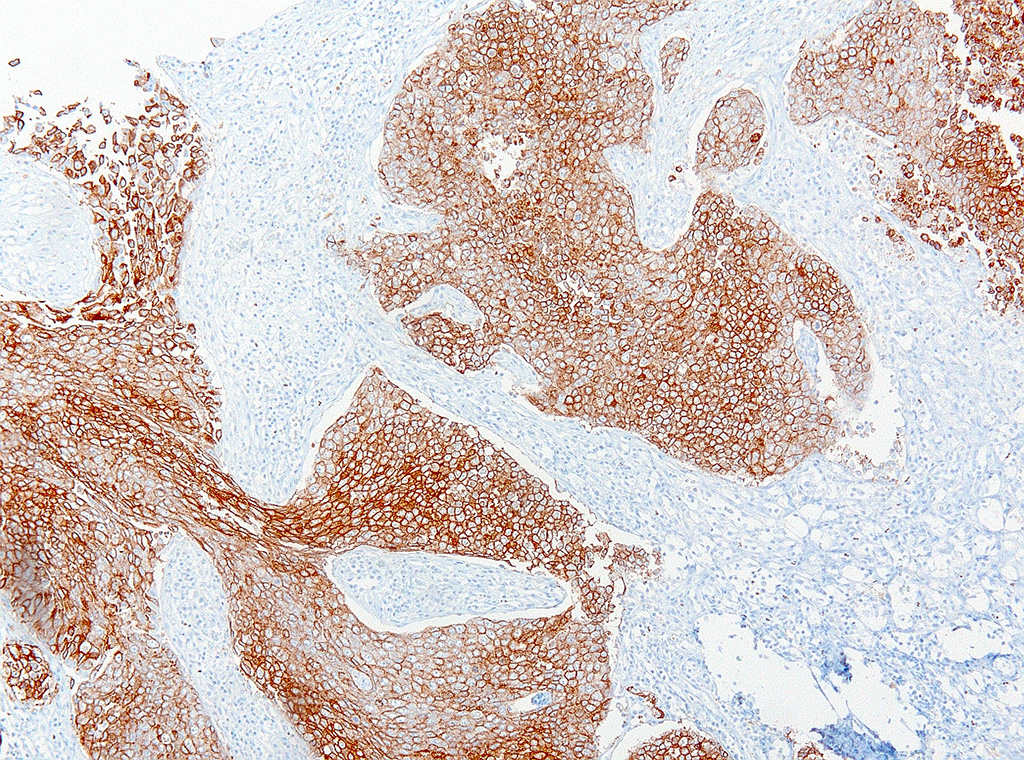

Various metastases of this neoplasm were found in lymph nodes, liver, lung, adrenal gland, and eye. These metastases stained positive for uroplakin.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Bovine viral diarrhea I&II PCR of lymph node: Negative

Aerobic culture of lung: Pasteurella multocida, heavy growth

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Most TCCs are found in the trigone of the bladder8 and have a papillary, polypoid, or sessile morphology.9 Various patterns of TCCs have been described, with the papillary and infiltrating TCC as the most common type and the nonpapillary, infiltrating type as the second most common.9 Some TCCs may originate in the ureter or urethra and might be more difficult to diagnose.5

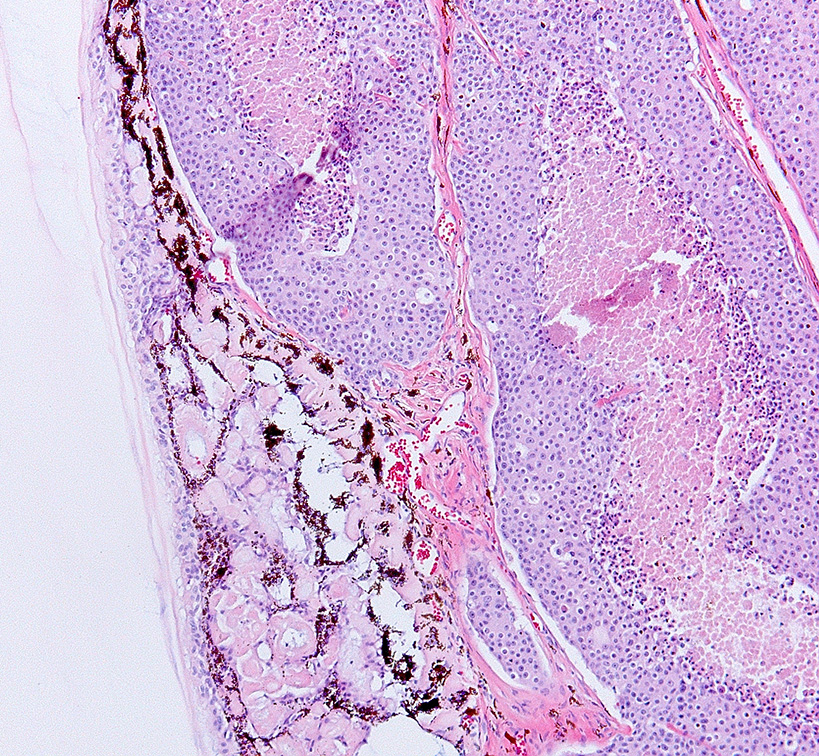

Histologically, nonpapillary infiltrating TCCs show a thickened bladder wall9 due to neoplastic growth of the urinary epithelium. Neoplastic cells are organized in small nests and form a multilobular pattern.5 Cyst-like structures may be visible, containing necrotic or keratinized debris may be seen.5 Neoplastic cells may show cystic degeneration and contain large cytoplasmic vacuoles, pushing the nucleus to the periphery creating a characteristic signet ring morphology. The large polygonal to round cells have distinct cell borders10, pale eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm5 and contain enlarged pleomorphic to polygonal and vesicular nuclei, with prominent nucleoli9 and clumped to reticular chromatin.3 Syncytial cells, atypical nuclei, mitotic figures are abundant.9 There might be variable desmoplasia and various amount of lymphoid inflammation. Vascular and lymphatic vessel invasion is often seen.9

The cause of TCC remains undetermined6, but is likely multifactorial.3 Environmental contaminants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons like benzopyrine have been suggested to play a role.5 Lipscomb et al. found intranuclear inclusion bodies in genital carcinoma and isolated a herpes virus (rhadinovirus) and an Epstein-Barr virus using PCR.6,7 Polychlorinated biphenyls could also contribute to the occurrence this neoplasm.10

TCCs metastasize in about 50% of the cases in domestic animals; first affecting regional lymph nodes before spreading to other organs.9 Metastases of TCC in Californian sea lions is also common, as in the current case3. The nonpapillary infiltrating type is the most likely to metastasize.9 Bilateral hydronephrosis due to obstruction by the neoplasm in either ureter or urethra is a possible associated lesion.9

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The mammalian urothelium is composed of 610 layers of cells that includes superficial, intermediate, and basal layers.2,12 The superficial layer, commonly known as the umbrella cell layer, contains a specialized plasma membrane that forms rigid plaques covering the apical surface of the urothelium. Uroplakin is one of the major protein components of the umbrella cells in the superficial layer and is highly conserved through most, if not all, mammalian species. The immunohistochemical stain, uroplakin-III, is marker for urothelial cells of the renal pelvis, ureter, bladder and urethra and has been used to detect transitional cell neoplasms in humans, dogs, cattle, and laboratory rodents. Loss of uroplakin-III expression in bladder cancers has been associated with malignant, invasive and anaplastic urothelial carcinomas in humans and dogs.2,12 Uroplakin-III is generally considered to be specific for urothelial carcinomas; however, positive immuno-reactivity for uroplakin-III has also been reported in prostatic carcinoma in humans and dogs.2,12 Positive immunostaining for uroplakin-III provides strong evidence for urothelial origin of the neoplasm in this case; however, further study may be needed to determine the specificity of uroplakin-III in the genital and urinary tract in California sea lions.

Invasive and metastatic genital and urinary tract carcinomas are commonly diagnosed in stranded California sea lions. As mentioned by the contributor, these neoplasms have been associated with a number of predisposing causes, including otariine gamma herpesvirus6,7 infection and exposure to polychlorinated biphenyl water pollutants.3,10 Additionally, there is a reported association between development of urogenital carcinoma in sea lions with genetic homogenicity at the Pv11 microsatellite locus for the heparanase 2 gene (HPSE2).1 Homogenicity at this site is also strongly correlated with decreased overall fitness within the stranded California sea lion population and may be secondary to inbreeding.1 Conference participants did not note eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies characteristic of herpesvirus infection in this tissue section.

References:

1. Browning HM, Acevedo-Whitehouse K, et al. Evidence for a genetic basis of urogenital carcinoma in the wild California sea lion. Proc Biol Sci. 2014; 281(1796):20140240.

2. Charney VA, Miller MA, et al. Skeletal metastasis of canine urothelial carcinoma: Pathologic and computed tomographic features. Vet Pathol. 2016; pii:0300985816677152. [Epub ahead of print].

3. Colegrove KM, Gulland FMD, Naydan DK, et al. Tumor morphology and immuno-histochemical expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, p53, and Ki67 in urogenital carcinomas of California sea lions (Zalophus Californianus). Vet Pathol. 2009; 46:642-655.

4. Dierauf, L, Gulland FMD. CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine: Health, Disease, and Rehabilitation. CRC press; 2001.

5. Gulland, FMD, Trupkiewicz JG, Spraker TR, et al. Metastatic carcinoma of probable transitional cell origin in 66 free-living California sea lions (Zalophus Californianus), 1979 to 1994. J Wildl Dis.1996; 32:250258.

6. Lipscomb TP, Scott DP, Schulman FY. Primary site of sea lion carcinomas. Vet Pathol. 2010; 47:185.

7. Lipscomb TP, Scott DP, Garber RL, et al. Common metastatic carcinoma of California sea lions (Zalophus Californianus): Evidence of genital origin and association with novel gammaherpesvirus. Vet Pathol. 2000; 37:60917.

8. Martineau D, Lagace A, Masse R, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in a beluga whale (Delphinapterus Leucas). Can Vet J. 1985; 26:297.

9. Meuten DJ, Everitt J, Inskeep W, et al. Histological Classification of Tumors of the Urinary System of Domestic Animals. 2nd ed. Vol. XI. Second Series. Washington; DC: World Health Organization and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 2004.

10. Newman SJ, Smith SA. Marine mammal neoplasia: A review. Vet Pathol. 2006; 43:865880.

11. Van de Velde N, De Laender P, Chiers K. Transitional cell carcinoma metastasizing to different organs including the eye in a California sea lion (Zaliophus californianus). J Comp Pathol. 2017; 156(1):132.

12. Wilson CJ, Flake GP, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of cyclin D1, cytokeratin 20, and uroplakin III in proliferative urinary bladder lesions induced by o-nitroanisole in Fischer 344/N rats. Vet Pathol. 2016; 53(3):682-690.