Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 19, Case 1

Signalment:

22 year old, female, Green anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

History:

This snake was humanely euthanized due to a persistent Ophidiomyces infection with clinical signs (not specified), despite over 6 months of treatment with terbinafine.

Gross Pathology:

Necropsy was performed by the clinicians, and formalin-fixed tissues were sent to our laboratory for histopathologic exam. The clinicians reported multifocal areas of brown discoloration on the ventral scales. Corneas were reported to be cloudy. There were multifocal yellow nodules in the lungs.

Laboratory Results:

Antemortem skin swab submitted to the Illinois Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory was positive via qPCR for Ophidiomyces

Postmortem, panfungal PCR at the University of Florida did not detect Ophidiomyces in paraffin-embedded lung tissue.

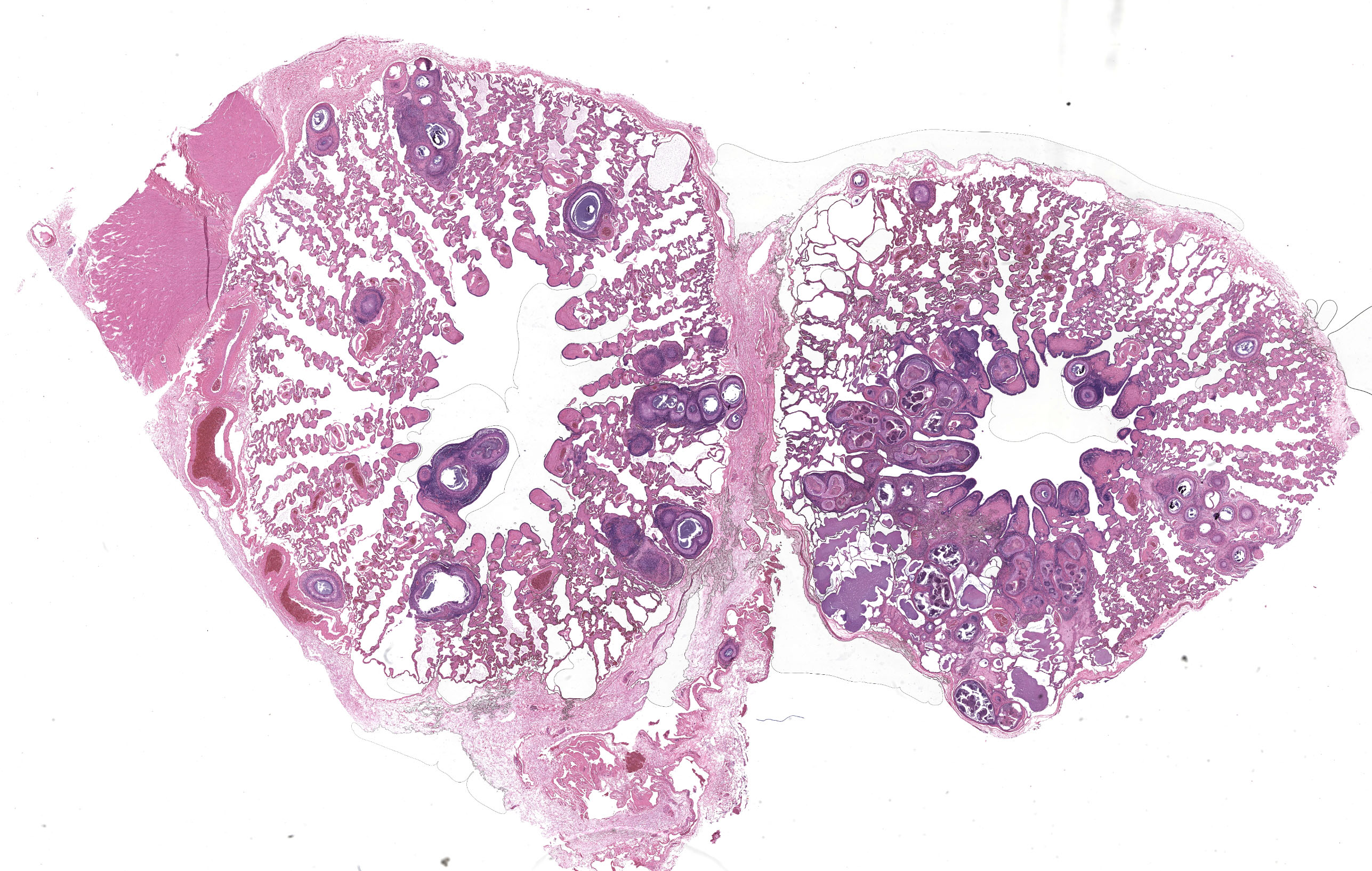

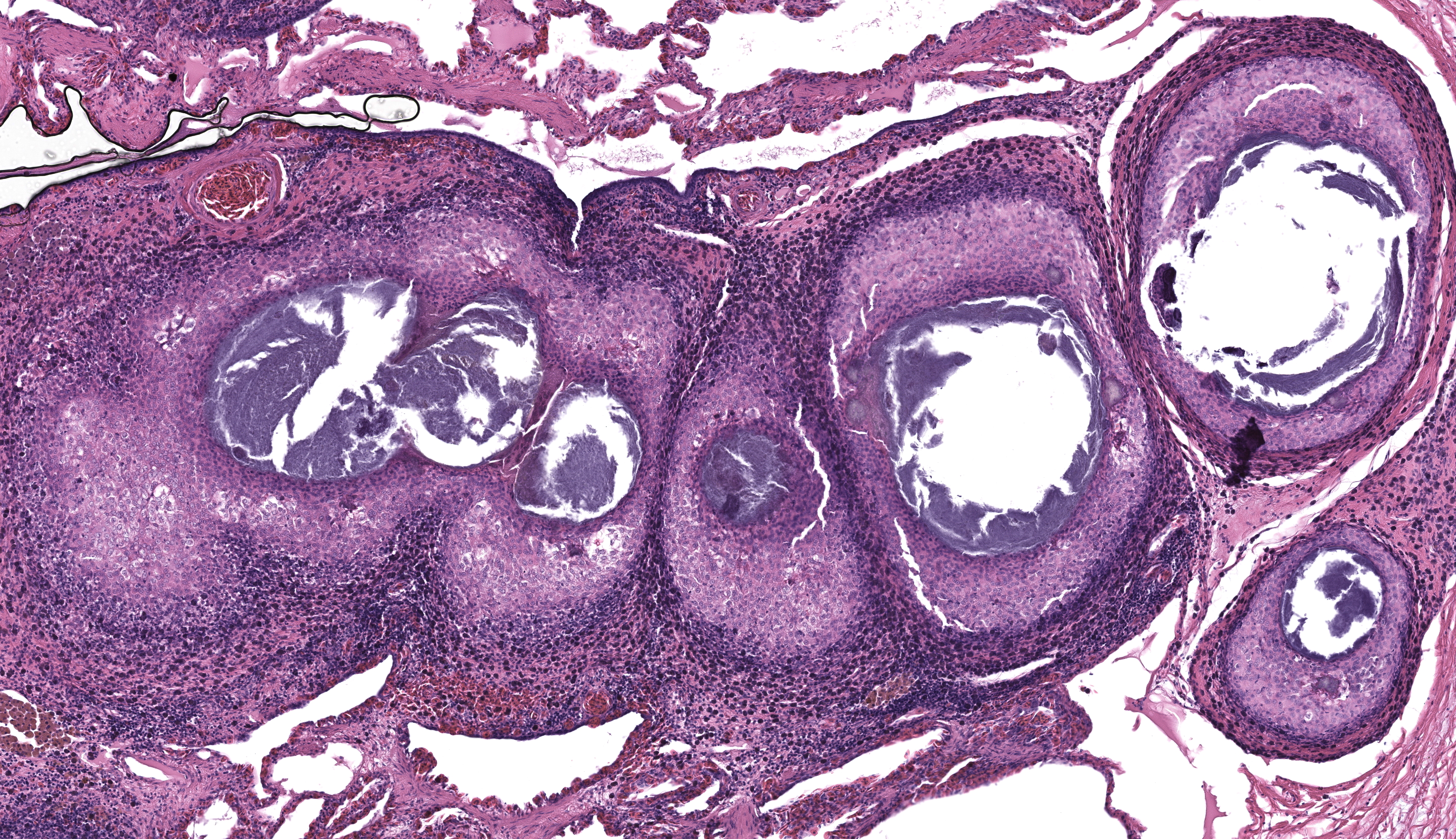

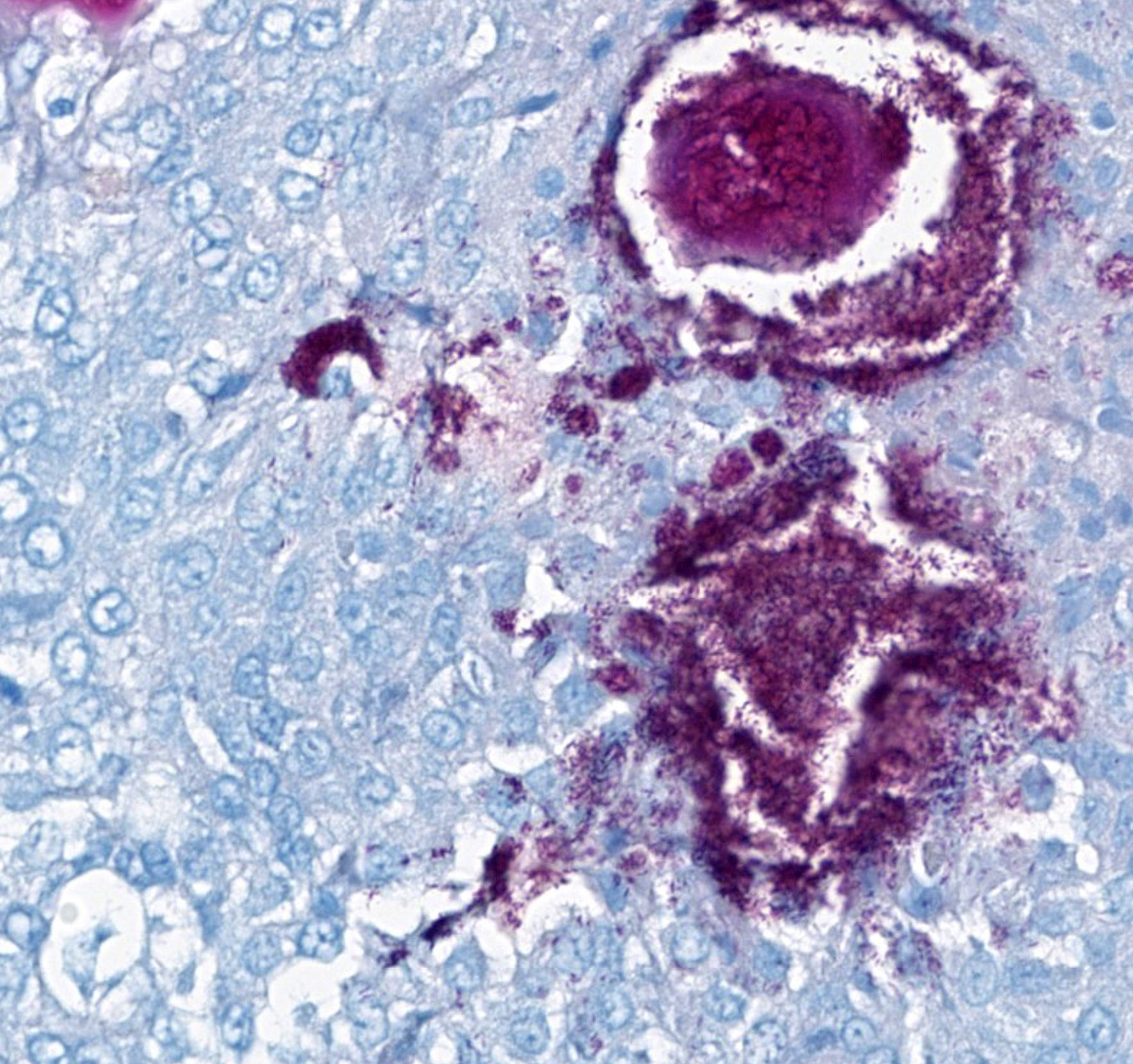

Microscopic Description:

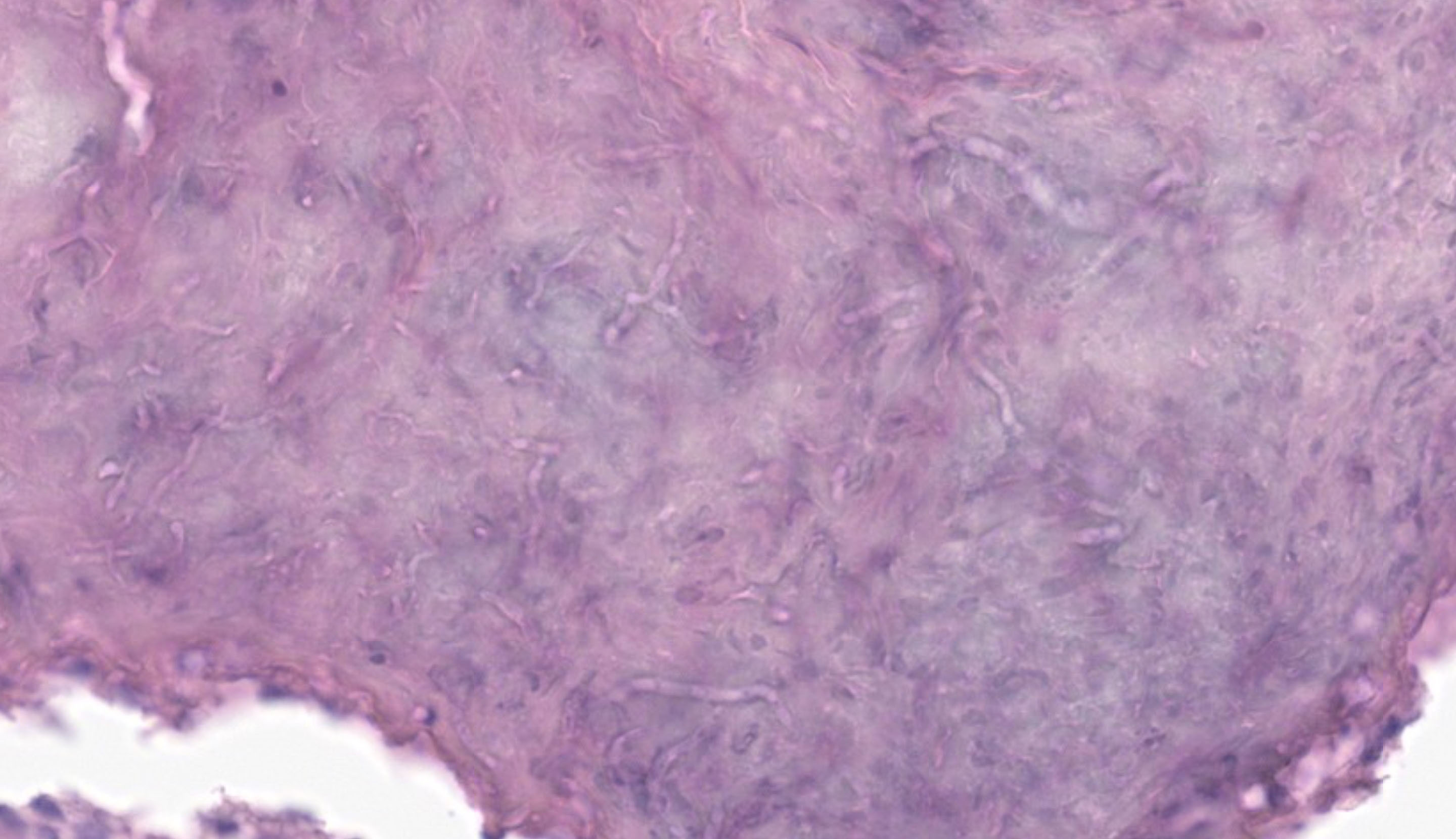

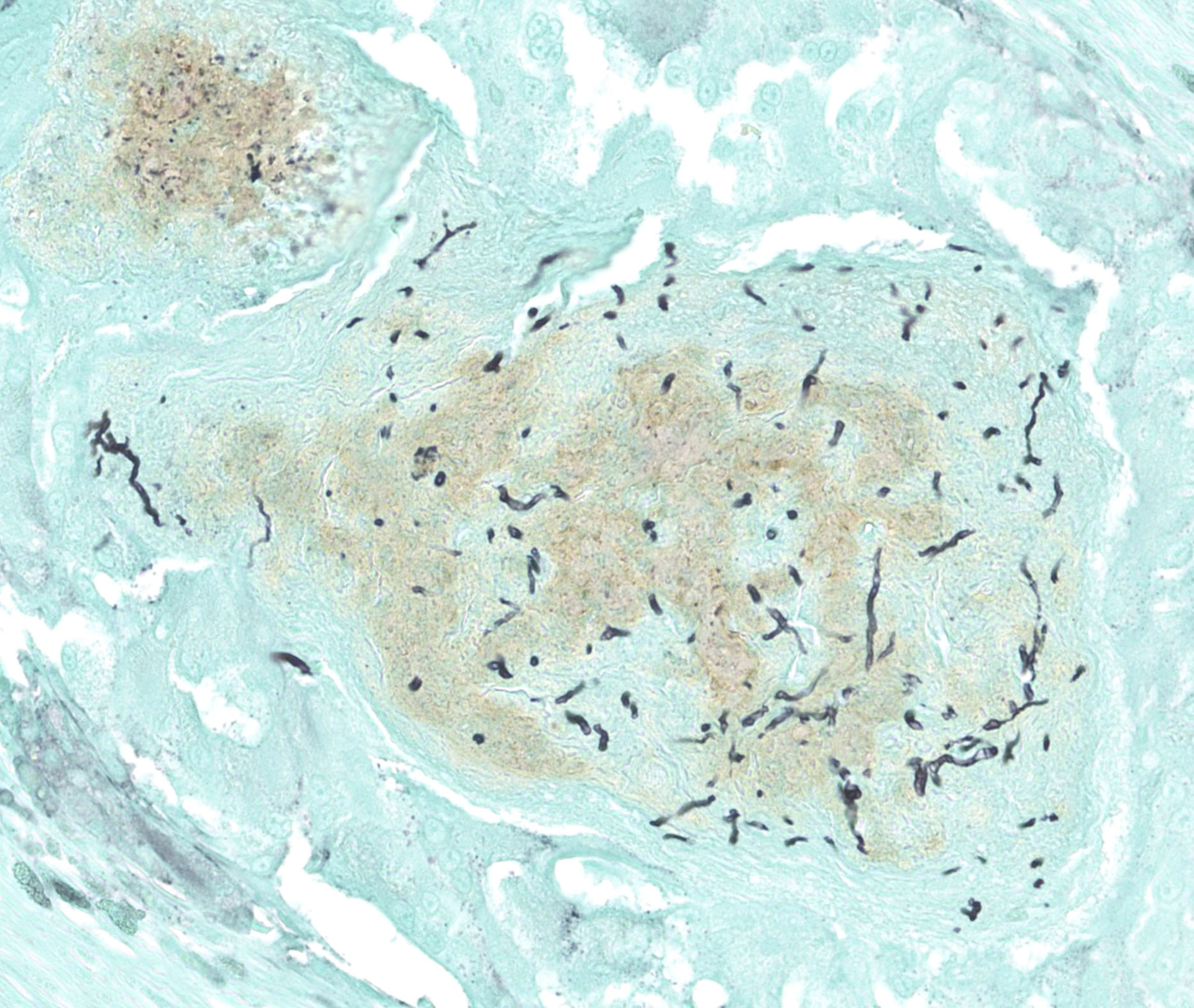

Randomly distributed in the lungs are multifocal to coalescing nodules composed of central areas of amorphous, eosinophilic to occasionally mineralized, necrotic debris. This central necrotic material is surrounded by moderate to high numbers of macrophages, with lymphocytes and plasma cells present at the periphery. In some granulomas, fungal hyphae that are 2-3 um wide, with parallel walls, septa, and occasional acute angle branching, stain positive with Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic-acid-Schiff (PAS) stains.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lungs: Multifocal granulomatous pneumonia with fungi

Contributor’s Comment:

This case highlights a granulomatous pneumonia caused by a fungus with histologic features consistent with Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola. The fungal infection is presumed to have originated from the dermal Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola infection detected antemortem via qPCR in dermal lesions found on this captive, green anaconda.

Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola is the causative agent of “snake fungal disease”. First described in eastern massasauga rattlesnakes in Illinois, USA, in 2011, it was originally characterized as an emerging infectious disease.1,2 It has since been described in the eastern to mid-western United States, Canada, Europe, and in Australia.2,3,4,5 However, recent reviews suggest that O. ophiodiicola may be a common, endemic disease that was previously uncharacterized, rather than an emerging infectious agent.2,6 Retrospective testing found the earliest confirmed infection to be 1986, and there does not appear to be an increase over the last decade in the prevalence of O. ophiodiicola or change in its distribution, at least in North America.2

Originally classified within the chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii complex, it was initially unclear if O. ophiodiicola was a primary or opportunistic pathogen.7 Later experimental infections of corn snakes with O. ophiodiicola confirmed a casual link between O. ophiodiicola and lesions consistent with those seen in wild snakes with snake fungal disease. In addition, they found that variation of described clinical signs in the literature may be explained by the stage of infection.7 Increased frequency of molting, anorexia, and abnormal behaviors such as resting in conspicuous areas were also observed.7

The clinical presentation can vary, but typically, O. ophiodiicola produces a fungal dermatitis characterized by early superficial dermatitis and scale loss, and severe and chronic infections can result in extensive ulceration, facial swelling and disfiguration.1,3,8 Histologically, lesions range from heterophilic to necrotizing epidermitis, with or without granulomatous dermatitis, granulomatous pneumonia, granulomatous endophthalmitis, and subcutaneous/intramuscular granulomas.6 Systemic infections have been described.9

In addition to histopathology and histochemical stains, fungal culture and PCR are recommended for definitive diagnosis.3 In this case antemortem dermal swabs were positive for Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola via qPCR. Postmortem panfungal PCR of paraffin-embedded lung tissue did not detect Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola, but did detect Malassezia sp, a presumed contaminant, given histologic features of the fungus. Given the antemortem qPCR positive, and histologic features, a presumptive diagnosis of granulomatous pneumonia due to Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola was made. It is likely that prolonged formalin fixation interfered with amplification of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola in this case.

Contributing Institution:

https://nmdeptag.nmsu.edu/labs/veterinary-diagnostic-services.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, granulomatous, chronic, multifocal, moderate, with fungal hyphae.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Lauren Peiffer of Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute who explored bird and reptile cases with conference participants. This first case in a green anaconda is a rare look at a snake lung with marked ancillary changes to accompany prominent granulomas. The faveolar septa are expanded either by fibrosis and/or smooth muscle hyperplasia and contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages which reinforce the chronicity of the overall process. Fungal elements are apparent in select granulomas on H&E, but their mophology is better appreciated with GMS and PAS stains. In particular, PAS(with malachite green counterstain) was helpful for detailing septation and contour of hyphae which was consistent with Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola.

Dr. Peiffer discussed differentials for lung granulomas in snakes with mycobacteriosis being an important rule out. We performed modified Gram stains (Brown-Brenn, Brown-Hopps) and acid-fast stains (Fite-Faraco, Ziehl-Neelsen) which identified gram-positive bacilli with some granulomas that were highlighted with Fite-Faraco, but not Ziehl-Neelsen. These findings are consistent with Mycobacterium sp. and concurrent infectious agents are a common finding in granulomatous inflammation. Multiple species of mycobacteria have been reported in snakes, including M. marinum, M. haemophilum, M. kansasii, M. chelonae, and M. leprae.10

We agree with the contributor that the finding of Malassezia on the panfungal PCR is probably spurious and second the notion to compare the results of ancillary diagnostics in assessing their validity. Malassezia restricta is a common contaminant and in this case may have been preserved within the paraffin block or sampled from the operator or lab environment itself. The lack of recovery of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola may reflect degradation of DNA in formalin – given the large number of hyphae present in section, we do not believe that prolonged antifungal therapy was probably not a factor.

References:

- Allender MC, Dreslik M, Wylie S, Phillips C, Wylie DB, Maddox C, Delaney MA, Kinsel MJ. Chrysosporium sp. infection in eastern massasauga rattlesnakes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Dec;17(12):2383-4.

- Davy CM, Shirose L, Campbell D, Dillon R, McKenzie C, Nemeth N, et al. Revisiting Ophidiomycosis (Snake Fungal Disease) After a Decade of Targeted Research. Front Vet Sci. 2021; 8: 665805.

- Ossiboff R. In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Terio K, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. London, Academic Press, 2018: 912-914.

- Franklinos LHV, Lorch JM, Bohuski E, Rodriguez-Ramos Fernandez J, Wright ON, Fitzpatrick L, Petrovan S, Durrant C, Linton C, Balá? et al. Emerging fungal pathogen Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola in wild European snakes. Sci Rep. 2017 Jun 19;7(1):3844

- Sigler L, Hambleton S, Paré JA. Molecular characterization of reptile pathogens currently known as members of the chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii complex and relationship with some human-associated isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2013 Oct;51(10):3338-57.

- Anderson KB, Steeil JC, Neiffer DL, et al. Retrospective review of Ophidiomycosis (Ophidiomyces ophidiicola) at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park (1983-2017). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 52(3), 997-1002

- Lorch JM, Lankton J, Werner K, Falendysz EA, McCurley K, Blehert DS. Experimental Infection of Snakes with Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola Causes Pathological Changes That Typify Snake Fungal Disease. mBio. 2015 Nov 17;6(6):e01534-15.

- Last LA, Fenton H, Gonyor-McGuire J, Moore M, Yabsley MJ. Snake fungal disease caused by Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola in a free-ranging mud snake (Farancia abacura). JVDI . 2016;28(6):709-713.

- Dolinski AC, Allender MC, Hsiao V, Maddox CW. Systemic Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola Infection in a Free-Ranging Plains Garter Snake (Thamnophis radix). Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 2014; 24 (1-2): 7–10

- Ebani VV. Domestic reptiles as source of zoonotic bacteria: A mini review. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017 Aug;10(8):723-728.