Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 13

8 January 2020

CASE III: 18-2108 WSC #3 HE (JPC 4117383).

Signalment: 3-1yr female red golden pheasant (Chrysopholus pictus)

History: A pheasant flock of 50 birds was experiencing respiratory signs, including nasal congestion, puffy eyes, and ocular discharge. Twelve pheasants died over approximately one month. The owner purchased an additional 12-16 new pheasants from Michigan and Ohio. These new pheasants seemed thin, weak, and lethargic. They were introduced directly into the original flock without a quarantine period. There were no further deaths in the original flock, but eight of the new pheasants died within a three-week period. This golden pheasant was submitted for necropsy together with two Impeyan pheasants for necropsy, both of which had a severe mucopurulent infraorbital sinusitis and rhinitis.

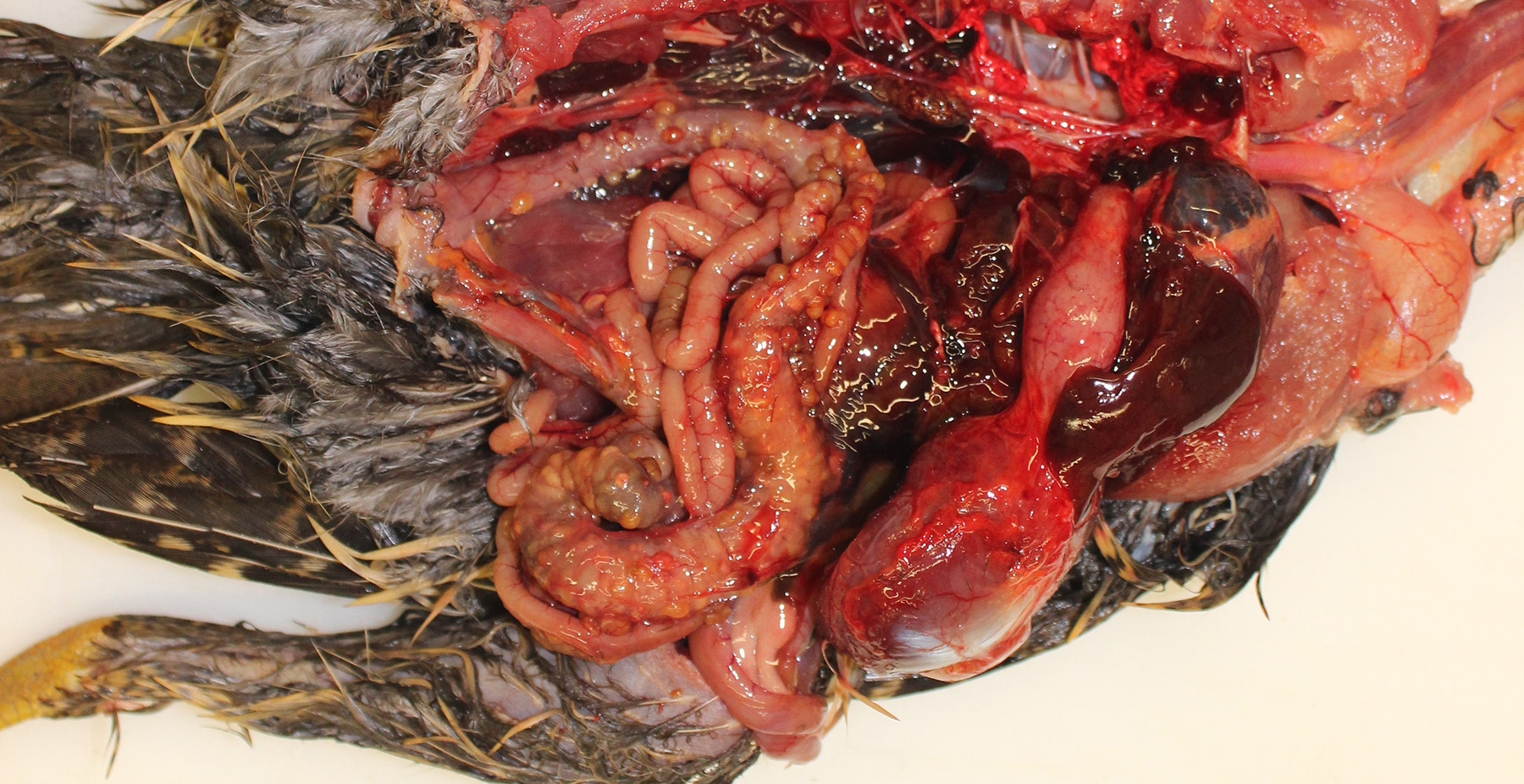

Gross Pathology: The pheasant weighed 470g and was in good body condition. There were innumerable firm yellow to reddened nodules each up to 3mm in diameter covering the serosal surfaces of the distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract, affecting the ceca most severely but with additional nodules over the colorectum, ileum, and distal jejunum. These nodules were also present in the mucosa of the ceca. No gross lesions were identified in the nasal cavities, trachea, or lungs of this pheasant.

Laboratory results:

Aerobic and Mycoplasma cultures from the affected sinuses of the two Impeyan pheasants yielded no growth.

Microscopic Description:

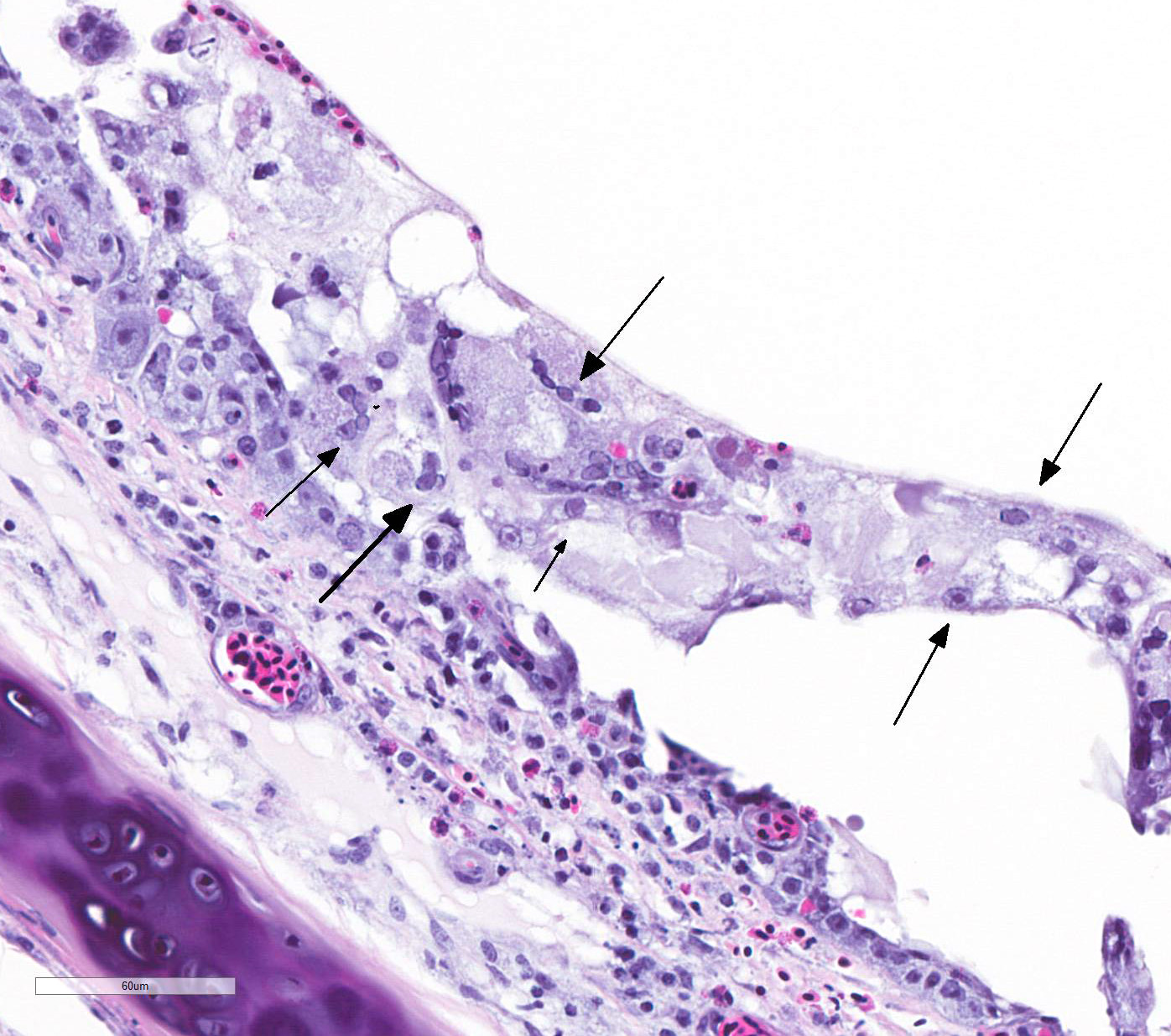

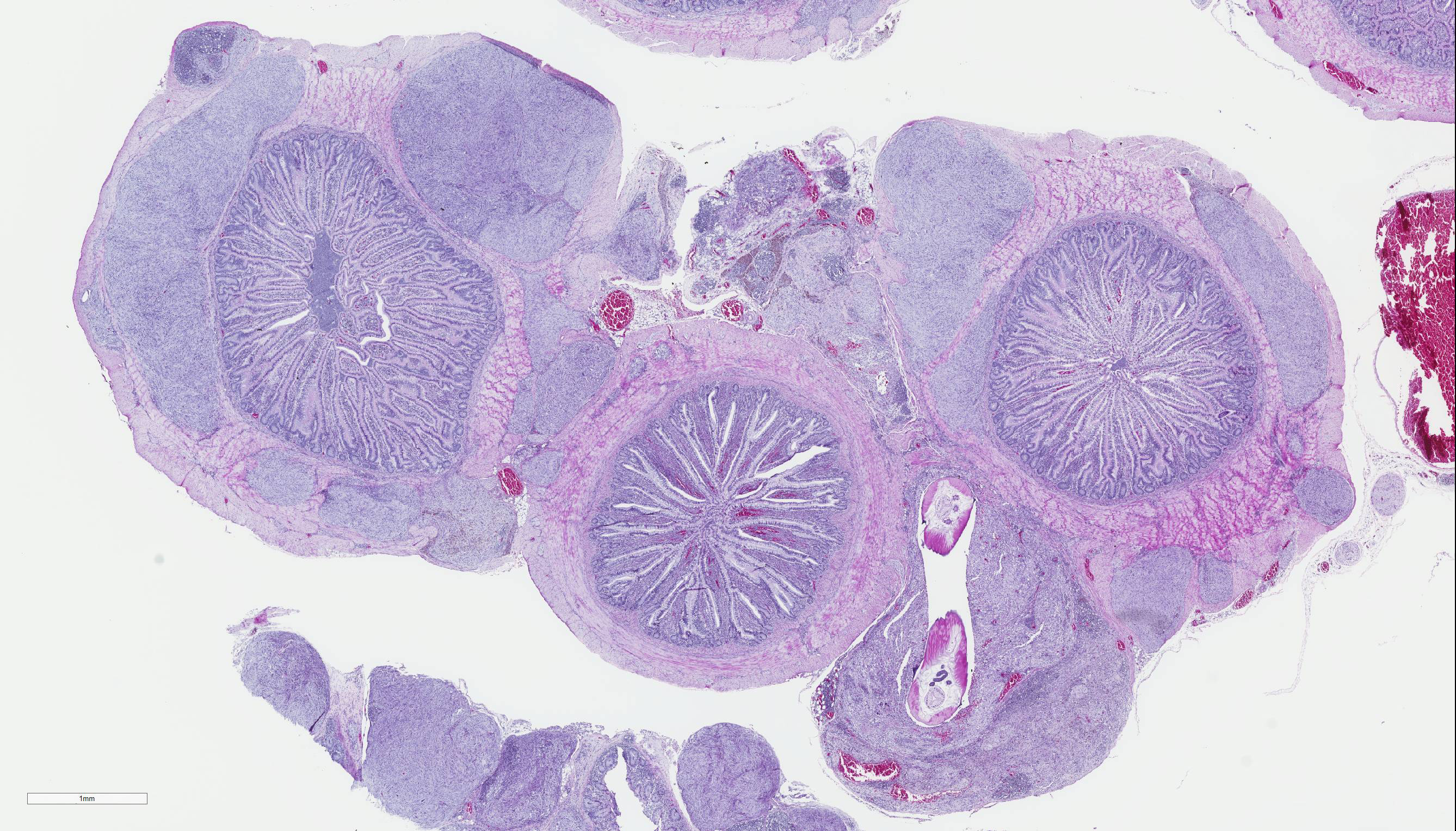

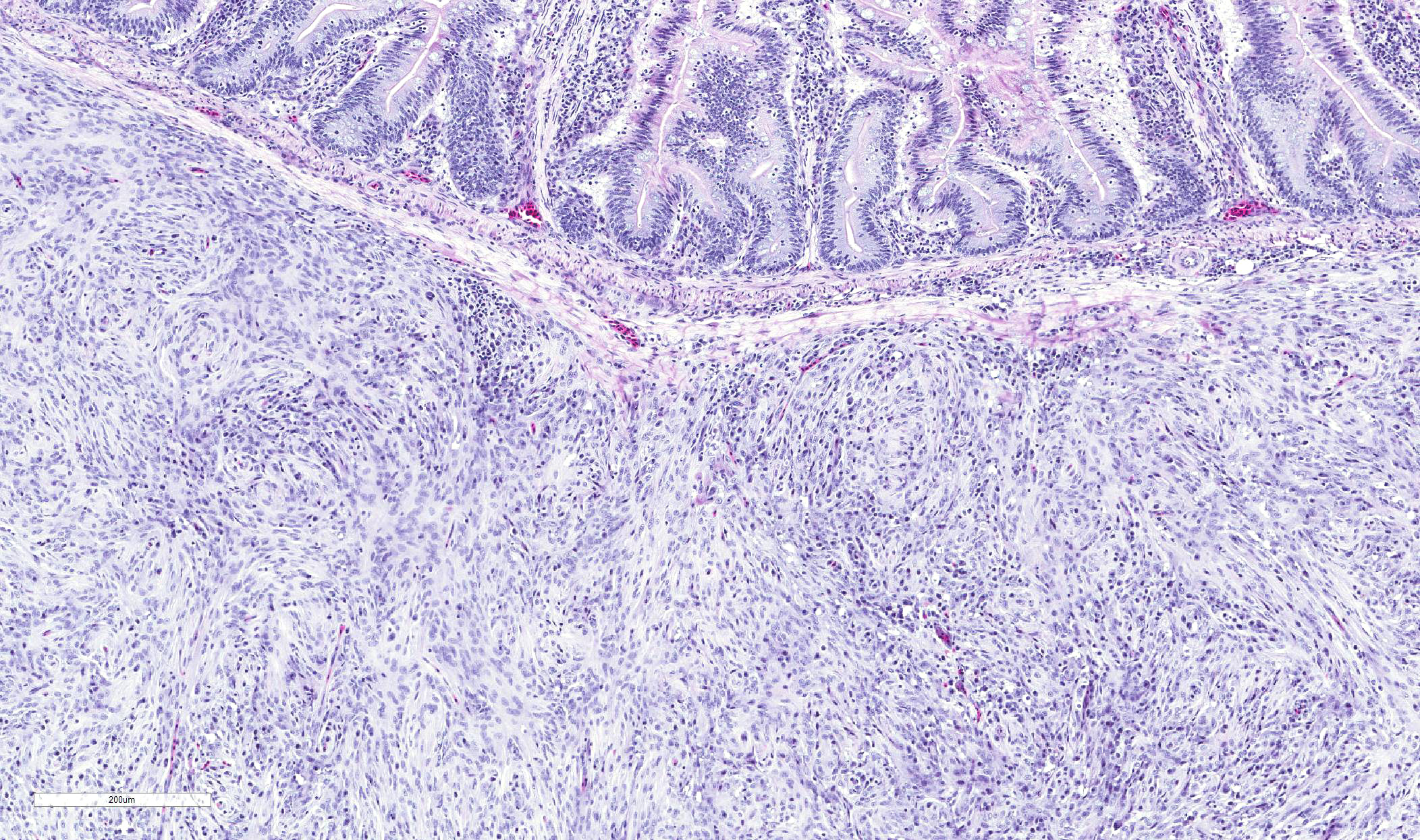

Cecum, ileum, and colorectum: Many

well-circumscribed nodules, each up to 3mm in diameter and becoming confluent,

expand the submucosa, muscularis externa and serosa, and are sometimes

pedunculated from the serosal tissue. The cecum is most severely affected.

Nodules consist primarily of spindle cells with a large volume of pale

eosinophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders, having large round to oval

nuclei with vesicular chromatin and a prominent nucleolus. Cells are arranged

in whorls, and sometimes interlacing streams and bundles. Nodules are

infiltrated by mild to moderate numbers of macrophages and small lymphocytes

with fewer plasma cells, and are surrounded by a thin collagenous capsule.

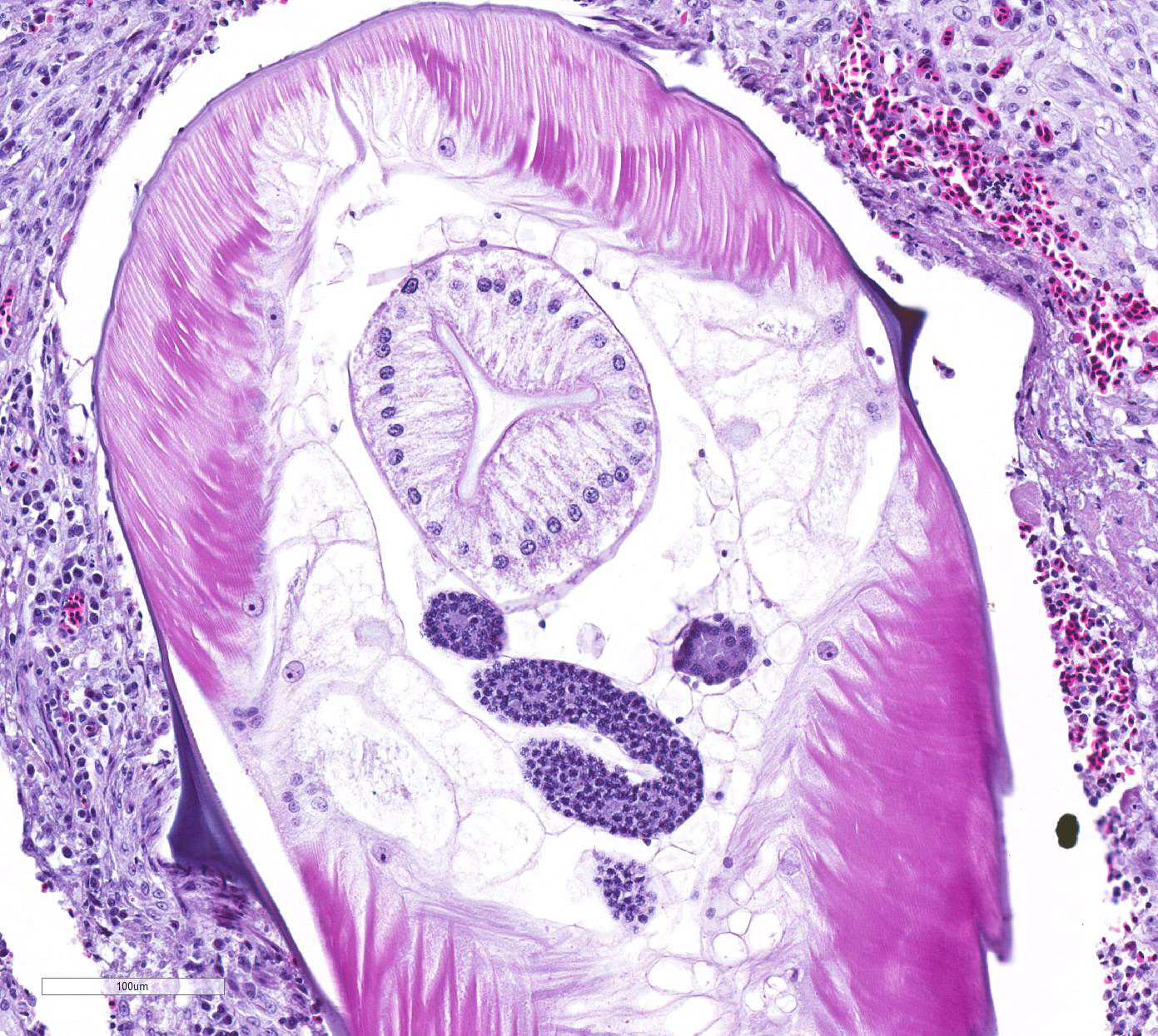

Many of these nodules contain nematode parasites of 0.3mm in diameter in cross

section or tangential section. Nematodes are characterized by a thin smooth

cuticle with lateral alae and a thin hypodermis, large lateral chords, and

thick polymyarian, coelomyarian musculature. A pseudocoelom contains a

distinct digestive tract with columnar enterocytes, and non-embryonated eggs

are present in a uterus in some sections. Some of these nematodes are

degenerate and fragmented and are surrounded by increased numbers of

leukocytes, including multinucleated giant cells and heterophils. There is

moderate congestion of vessels within some nodules with occasional

extravasation of erythrocytes, and there are occasional aggregates of

hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Additional nematodes are rarely present in the

cecal lumen. There is some variation among slides and sections.

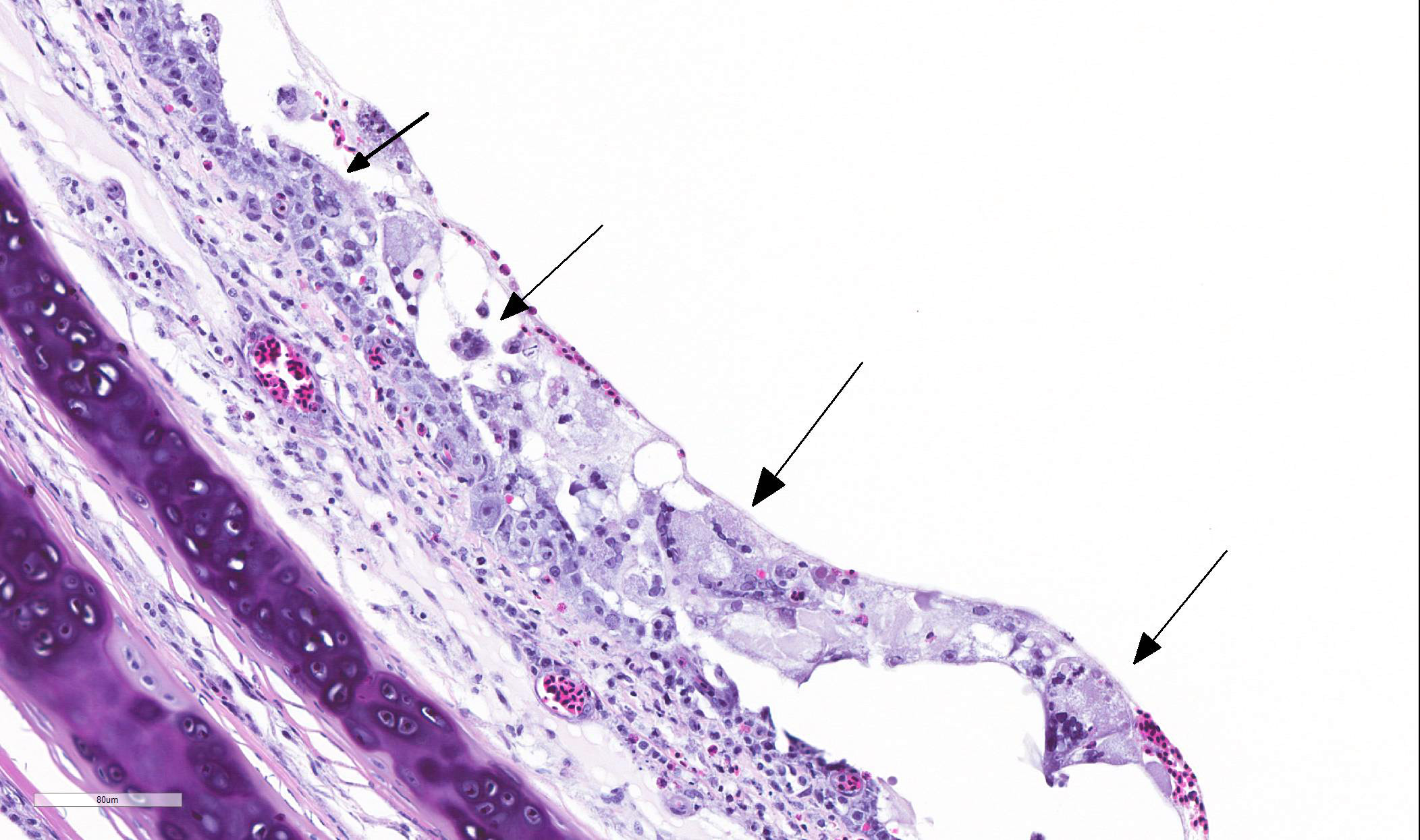

TRACHEA: There is circumferential erosion of the tracheal epithelium, and the

tracheal mucosa is covered by a thin pseudomembrane composed of fibrillar

eosinophilic material (fibrin) admixed with heterophils, sloughed degenerate

cells, and small numbers of erythrocytes. The epithelium contains large

syncytial cells with up to 25 nuclei, which slough into the tracheal lumen.

Nuclei in syncytial cells often contain large hyaline eosinophilic to

basophilic viral intranuclear inclusions that peripheralize the chromatin.

Individual epithelial cells sometimes contain amphophilic to basophilic

inclusions. Cilia are absent from most of the remaining epithelium which is

attenuated to a low cuboidal level in certain areas, while in other areas there

is a reparative process where epithelium is 4-5 cells thick and disorganized, and

nuclei are large with prominent nucleoli. The subjacent submucosa is expanded

by edema and low to medium numbers of heterophils, macrophages, and

lymphocytes; mucus glands are not seen.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cecum, ileum, and colorectum: Atypical nodular mesenchymal proliferation, submucosal, mural and serosal, severe, with granulomatous inflammation and intralesion adult nematodes, morphology consistent with Heterakis spp.

Trachea: Tracheitis, fibrinonecrotizing, diffuse, severe, with epithelial syncytia formation and intranuclear viral inclusion bodies, consistent with gallid herpesvirus-1.

Contributor Comment: The microscopic findings in this pheseant are characteristic for gallid herpesvirus type 1 (GaHV-1), the cause of infectious laryngotracheitis, and for Heterakis infection.

GaHV-1 is a member of the genus Iltovirus, subfamily alphaherpesviridae of the herpesviridae family3. The disease was first described in poultry in the United States in 19253, and in pheasants in 1931. Pheasants, pea fowl, and very young turkeys are also susceptible, while quail, guinea fowl, and non-galliform birds are resistant.2 Birds that survive become lifelong carriers that may continue to shed, and wind can carry the virus between backyard flocks and larger production facilities. The virus is susceptible to disinfectants and to light exposure, but can survive in moist litter for 4 days or in dry litter for 20 days. Naturally infected birds develop clinical illness 6-14 days post-exposure.3 Viral replication is limited to the respiratory epithelium; latency is achieved by infection of the trigeminal ganglion.3 Birds affected in an epizootic can develop bloody mucus throughout the upper respiratory tract and experience severe respiratory distress and high mortality, while enzootic forms can cause varying degrees of mucoid tracheitis, conjunctivitis, and sinusitis, with lower mortality.3

Though this bird did not have significant rhinitis or sinusitis on gross anatomic examination, the two Impeyan pheasants submitted concurrently did have marked exudates in their upper respiratory tracts, and characteristic intranuclear inclusions in sloughed syncytial cells were identified on histopathology on all three birds. These inclusions are pathognomonic and can be identified with hematoxylin and eosin stain or with Giemsa.3 Where GaHV-1 is suspected but inclusions are absent, viral isolation from chicken embryo liver cells, detection of GaHV-1 antigen by direct fluorescent antibody or immunohistochemical staining, or GaHV-1 DNA detection by PCR are appropriate.3 Serology is not generally advised due to cross-reactivity with vaccine-induced antibodies.3 Differential diagnoses for affected birds include infection by avian paramyxovirus (Newcastle disease), avian influenza, adenovirus infection, and avian coronaviruses.3

Heterakis spp infection is common in many galliform species. The life cycle is direct but earthworms may serve as paratenic hosts, making eradication of infection from birds on pasture or earthen lots exceedingly difficult.1,8 Heterakis dispar has been reported in pheasants and is relatively non-pathogenic, while H. gallinarum and H. isolonche have both been reported to cause typhlitis in pheasants. H. gallinarum is infrequently a major primary pathogen in poultry, however it serves as a transport host for the protozoal parasite Histomonas meleagridis, which causes blackhead disease in turkeys and sometimes in chickens. However, in pheasants, there are no reports of histomoniasis, and disease is due to the nematode itself.

Heterakis isolonche is usually more pathogenic and has been reported to cause high mortality in pen-reared pheasants.8 It causes extensive nodule formation in the distal digestive tract due both to granuloma formation and marked proliferative host response, with the ceca most severely affected. These nodules sometimes rupture, causing peritonitis/coelomitis.4 Second-stage larvae of H. isolonche are released from eggs in the gizzard, migrate to the ceca, then penetrate the mucosa1. In the submucosa, the larvae spark a proliferative response resulting in the yellow to pink to dark brown nodules seen grossly.1 The worms frequently reside in the nodules.1 Previous studies have variably characterized the nodules associated with these worms as granuloma, fibroma, fibrohistiocytic neoplasia, or leiomyoma, indicating the variability in response and limited studies attempting to characterize the proliferating cells. 4,5,6,9

While lesions are sometimes reported as benign neoplasia, there is a case report of metastatic lesions of neurofibroblastic origin developing in the lung and liver of a 9-year-old ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus).7

Some consider H. isolonche to be an example of a nematode that induces neoplasia.1 Spirocerca lupi is known to induce fibrosarcoma and osteosarcoma in the esophagus of dogs.12 In our case, trichrome stain revealed no collagen among the proliferating fusiform cells, and immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle actin and CD68 for cells of macrophage lineage were both negative, with appropriate staining of muscularis externa and individual inflammatory cells serving as appropriate internal positive controls, respectively. H. gallinarum and H. isolonche are very similar worms, and are usually differentiated at the gross level. H. isolonche is slightly longer that H. gallinarum, and its spicules are more symmetrical than those of H. gallinarum.8 In this case, intraluminal worms were not recognized grossly and are rarely seen on histologic section, features consistent with the life cycle of H. isolonche and not of H. gallinarum.

Of relevance to this case, there are multiple case reports describing increased pathogenicity in certain pheasant species including golden pheasants, though these cases do not describe the extensive involvement of the tunica muscularis externa or serosa of the ceca and surrounding digestive tract as seen in this bird.4,5,6,9. A cause for the increased disease severity in golden pheasants has not been elucidated, however parallels between the migrations of strongyles in equids, of hookworms in Southern fur seals, and of H. gallinarum in other galliform species may provide further insight. 4,11,12

Contributing Institution:

Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Connecticut,

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Trachea: Tracheitis, necrotizing and heterophilic, moderate with multifocal ulceration, epithelial intranuclear viral inclusion bodies and viral syncytia.

2. Cecum, large intestine, coelom: Typhlitis, colitis, and coelomitis, granulomatous, multifocal, moderate, with nodular spindle cell proliferations, and adult and larval ascarids.

JPC Comment: The participants agreed that this was a challenging descriptive exercise, with two distinct entities, as well as an adult nematode to describe. While most WSC submissions allow participants to focus on a single pathologic agent and process, there are two excellent unrelated conditions ongoing in this submission.

One of the

characteristics of infectious laryngotracheitis and a number of other alphaherpesviruses,

(to include herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, anatid herpesvirus-1, and a number of

others - but certainly not all) is the formation of characteristic syncytial

cells, (prominent in this particular specimen.) In ILT, syncytial cells are

commonly seen in the exudate overlying the remnants of the intact mucosa; these

are virally infected, mutated, and degenerating cells which have lost contact

with adjacent epithelium, a process that usually results in epithelial death.

In alphaherpesvirus infection, membrane fusion is a key element of initial cell

entry and lateral spread of virus in tissues It requires four envelope

proteins, gB, gD, gH, and gL. When mutated, the gB and gK genes confer

hyperfusogenicity on HSV and an accelerated and exaggerated process result in

the formation of syncytial cells. Essenctially, the formation of syncytia is a

normal process associated with viral transfection gone haywire as a result of

mutation.

The contributor has also done an excellent job in discussing the unique

proliferative change resulting from infection with H. isolonche in

pheasants. This precise histogenesis of these nodules have not to date been

elucidated. Immunostaining for smooth muscle, desmin, IBA-1, and histochemical

staining for collagen failed to identify a smooth muscle or histiocytic origin

for these nodules, and a literature review fails to elucidate their origin as

well. It is good to have some things that modern science cannot explain.

There are a few other species of Heterakis species of note. Heterakis

gallinarum in itself does not cause any significant disease, but is a host

for Histomonas melagridis, a protozoan parasite which causes necrotizing

typhlitis and hepatitis in turkeys and other poultry species. Heterakis bonasae

infects the ceca of ruffed grouse and bobwhite quail and heavy infections

may result in ill thrift and death . Heterakis spumosa is largely a

historical pathogen in laboratory rodents which infects the cecum or colon and

is not considered pathogenic.

The contributor mentioned parasites which may result in neoplasia in their host. Other examples include Opisthorchis felineus and Clonorchis sinensis which cause cholangiocarcinoma in cats and humans; Cysticercus fasciolaris which was documented to cause hepatic sarcoma in rats; Trichosomoides crassicauda which causes of the urothelium in rats; and Schistosoma haematobium a well-known cause of transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder in humans.

References:

1. Abdul-Aziz T, Barnes HJ. Heterakis isolonche Infection in Pheasants. In: Abdul-Aziz, T, Barnes, HJ. Gross Pathology of Avian Diseases: Text and Atlas. Madison, WI: Omnipress; 2018: 181.

2. Crawshaw GT, Boycott BR. Infectious Laryngotracheitis is Peafowl and Pheasants. Avian Dis. 1982; 2: 397-401.

3. García M, Spatz S, Guy JS. In: Swayne DE, ed. Diseases of Poultry 13th Ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013: 161-180.

4. Griner LA, Migaki G, Penner LR, McKee Jr. AE. Heterakidosis and Nodular Granulomas caused by Heterakis isolonche in the Ceca of Gallinaceous Birds. Vet Pathol. 1977: 582-590.

5. Halajian A, Kinsella JM, Mortazavi P, Abedi M. The first report of morbidity and mortality in Golden Pheasant, Chrysolophus pictus, due to a mixed infection of Heterakis gallinarum and H. isolonche in Iran. Turk J Vet Anim Sci. 2013; 37: 611-614.

6. Helmboldt CF, Wyand DS. Parasitic neoplasia in the golden pheasant. J Wildl Dis 1972; 8: 3-6

7. Himmel L, Cianciolo R. Nodular typhlocolitis, heterakiasis, and mesenchymal neoplasia in a ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) with immunohistochemical characterization of visceral metastases. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2017; 4: 561-565.

8. McDougald, LR. Internal Parasites. In: Swayne DE, ed. Diseases of Poultry 13th Ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013: 1123-1124.

9. Menezes RC, Tortelly R, Gomes DC, Pinto RM. Nodular Typhlitis Associated with the Nematodes Heterakis gallinarum and Heterakis isolonche in Pheasants: Frequency and Pathology with Evidence of Neoplasia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003; 8: 1011-1016.

10. Okubo Y, Uchida H, Wakata K, Suzuki T, Shibata T, Ikeda H, Tamaguch M, Cohen JB, Glorioso, JC, Tagaya M, Hamada H. Tahara H. Syncytial mutations do not impair the specificyt of entry and spread of a glycopeotein d receptor-retargeted herpes simplex virus. J of Virol 2016; 90(24)11096-1

11. Seguel M, Muñoz F, Navarette MJ, Paredes E, Howerth E, Gottdenker N. Hookworm Infection in South American Fur Seal (Arctocephalis australis) Pups: Pathology and Factors Associate with Host Tissue Damage and Pathology. Vet Pathol. 2017; 2: 288-297.

12. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology Of Domestic Animals 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 34-35.