Signalment:

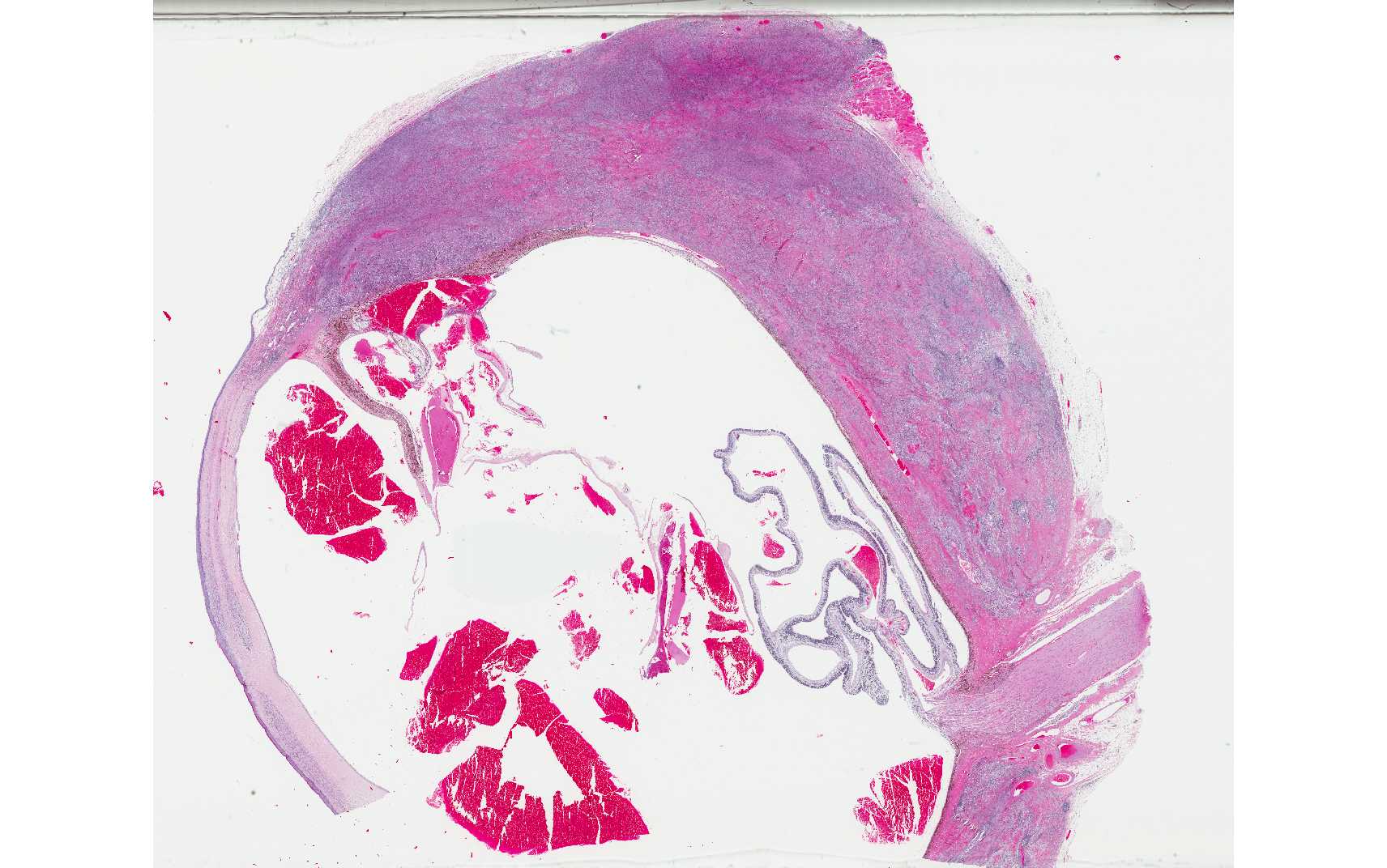

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Eye (left):

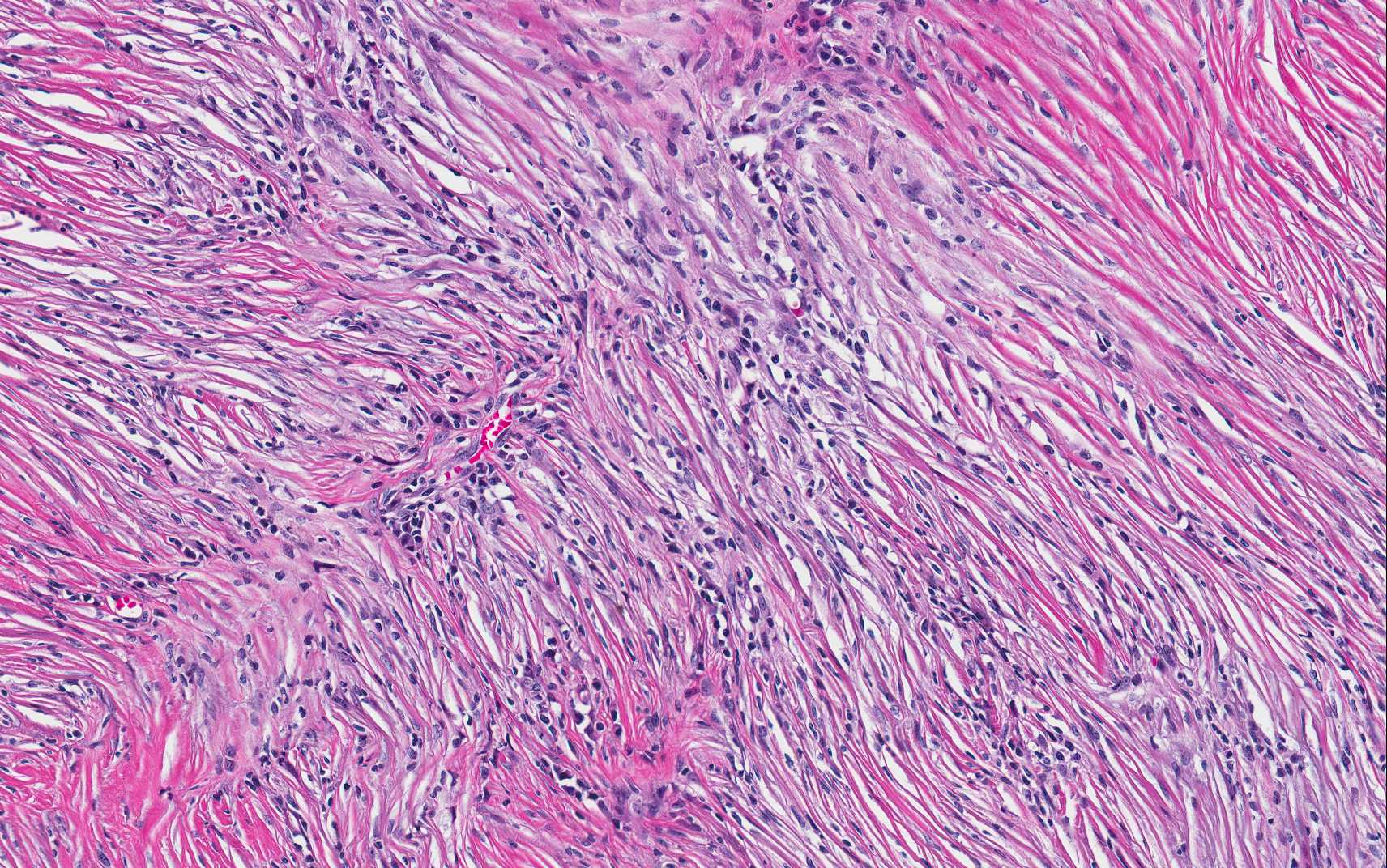

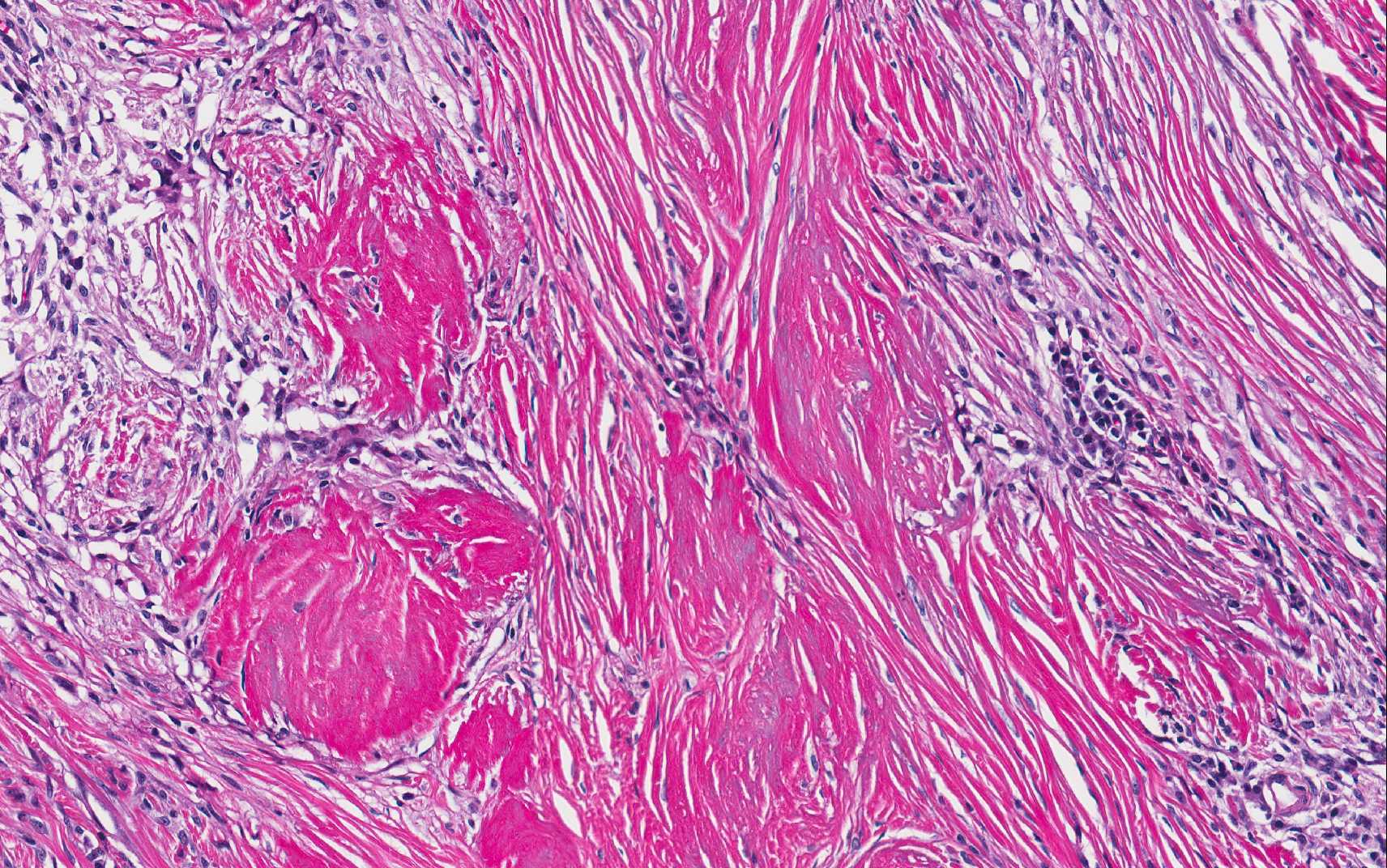

1. Severe granulomatous scleritis with altered collagen, consistent with necrotizing scleritis (also known as granulomatous scleritis).

2. Buphthalmia; corneal fibrosis, neovascularization, keratitis, and focal rupture of Descemets membrane (corneal stria); mild lymphoplasmacytic anterior uveitis with pre-iridal fibrovascular membrane, occlusion of filtration angle and hyphema; retinal detachment with inner retinal atrophy; and lens cataractous change.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The majority of scleral disease in dogs is inflammatory in nature and is most often the result of secondary involvement of the sclera with either intraocular inflammation or extension from an orbital cellulitis,7 as with a penetrating foreign body, trauma, or in-fectious etiology.5 Primary scleral/episcleral inflammation can be clinically divided into unilateral versus bilateral, nodular versus diffuse, and scleral versus episcleral categories, but there is often overlap in the clinical presentation of these entities and of secondary scleritis/episcleritis.5 One of the most common primary inflammatory diseases of the sclera/episcera is nodular granulomatous episcleritis, while necrotizing scleritis is rare in comparison.

Nodular granulomatous episcleritis, not present in this case, is also referred to as ocular nodular fasciitis, among other names, and is a proliferative nodular inflammatory lesion at the limbus of the eye that behaves somewhat like a neoplasm in its locally infiltrative growth.7 The histologic lesion consists of a proliferation of histiocytes, spindle cells and lymphocytes and plasma cells. The inflammation has a diffuse gran-ulomatous pattern, but discrete gran-ulomatous foci are not present, and collagenolysis is not a feature.7

Necrotizing scleritis, the disease entity in the present case, is also an inflammatory and proliferative process within the sclera, and has more recently been referred to by some as granulomatous scleritis.1,3 For the remainder of the discussion, this entity will be referred to as necrotizing scleritis, the more well-known name for the condition. In necrotizing scleritis, there is a similar composition of inflammatory cell types to that identified in cases of nodular gran-ulomatous episcleritis, including histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells and spindle cells. Some lesions also have a neutrophilic component, as in the present case, or an eosinophilic component.6 The two main distinguishing features of necrotizing scleritis from nodular granulomatous episcleritis are the formation of discrete granulomatous foci, and the presence of altered collagen (collagenolysis).6,7 The altered collagen is often surrounded by epithelioid macrophages to form the discrete granulomas. Altered collagen may have an abnormal tinctorial staining quality with Massons trichrome,2 which is identified in the present case as segmental red-staining of the collagen rather than the usual blue. The terms collagenolysis and collagen necrosis are somewhat controversial since collagen is considered inert and therefore cannot technically become necrotic. There is also often a granulomatous vasculitis, but this is not present in every case3. In the current case, although the inflammation appears somewhat vasocentric in some areas, overt vasculitis is not identified.

In necrotizing scleritis, the inflammation and spindle cell proliferation typically begins in the anterior sclera and slowly spreads circumferentially and posteriorly with eventual progression to involvement of the uvea and retina.7 On gross evaluation, the sclera is severely thickened and bright white.3 Staphyloma, which is a protrusion of uveal tissue through a weakened portion of the sclera, is a possible sequela in some cases, along with disinsertion of the extraocular muscles.4,5 Necrotizing scleritis is most commonly bilateral, but the second eye may not be affected until later in the course of the disease.3,7 It is critical to alert clinicians to the likelihood of involvement of the contralateral eye, given the important prognostic implications for vision3. The treatment for necrotizing scleritis is aggressive life-long anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy, but complete remission is rare and medical management fails in many cases, leading to enucleation of the affected eye(s).5,7

The pathogenesis of necrotizing scleritis is not well-understood. No etiologic agents have been identified in these cases,7 although necrotizing scleritis has been reported in dogs with ehrlichiosis.3 An immune-mediated pathogenesis has been suggested, particularly due to the co-mparable lesion in humans, which is an autoimmune disease process, as well as the partial response to immunosuppressive therapy in dogs.1,2,5 Most cases reported appear to be localized to the eye, with rare reports that have evidence for other systemic immune-mediated disease, which is the case for humans with necrotizing scleritis.1 There is some evidence for a type III and type IV hypersensitivity mechanism to the pa-thogenesis of necrotizing scleritis in dogs, but there is variability in the literature as to whether T- or B-lymphocytes predominate in the lymphocytic component of the inflammation.1,2 Some pathologists have made the comparison between necrotizing scleritis and systemic reactive histiocytosis in dogs and consider that these entities may be related (personal communication, R. Dubielzig). This is in particular due to the vasocentric nature of the cellular infiltrate in necrotizing scleritis (personal communication, R. Dubielzig).

In conclusion, this case is a classic example of necrotizing scleritis in the eye of a dog, highlighting the characteristic histologic features of this condition including the granulomatous inflammation and the altered collagen within the lesion.

JPC Diagnosis:

1.Eye, sclera: Scleritis, granulomatous and sclerosing, focally extensive, severe with optic nerve demyelination.

2.Eye: Panuveitis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, diffuse, moderate with hyphema, pre and post iridial fibrovascular membranes, retinal detachment and atrophy, and hypermature cataract.

Conference Comment:

References:

1. Day MJ, Mould JRB and Carter WJ. An immunohistochemical investigation of canine idiopathic granulomatous scleritis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2008;11:11-17.

2. Denk N, et al. A retrospective study of the clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical manifestations of 5 dogs originally diagnosed histologically as necrotizing scleritis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2012; 15:102-109.

3. Dubielzig RR. Diseases of the cornea and sclera. In: Veterinary Ocular Pathology a comparative review. Saunders Elsevier: New York, NY; 2010: 232-234.

4. Grahn BH, Cullen CL and Wolfer J. Diagnostic ophthalmology, Necrotic scleritis and uveitis. Can Vet J. 1999; 40:679-680.

5. Grahn BH and Sandmeyer LS. Canine episcleritis, nodular episclerokeratitis, scleritis, and necrotic scleritis. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2008;38:291-308.

6. Njaa BL and Wilcock BP. The ear and eye. In: Zachary and McGavin, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. Mosby Elsevier: St. Louis, MO; 2012:1153-1244.

7. Wilcock BP. Eye and ear. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Saunders Elsevier: Philadephia, PA; 2007:459-552.