Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 15

January 17th, 2018

CASE III: LJ84 (JPC 4101222).

Signalment: 1-year-old, male, Indian rhesus macaque, Macaca mulatta, primate.

History: Received bivalent pneumococcal/salmonella vaccination a year prior and 100 TCID50 of SIVmac251 intravenously five months prior to submission. Initially presented with soft stool and distended abdomen 2 weeks prior to being discovered recumbent with nystagmus and head tilt.

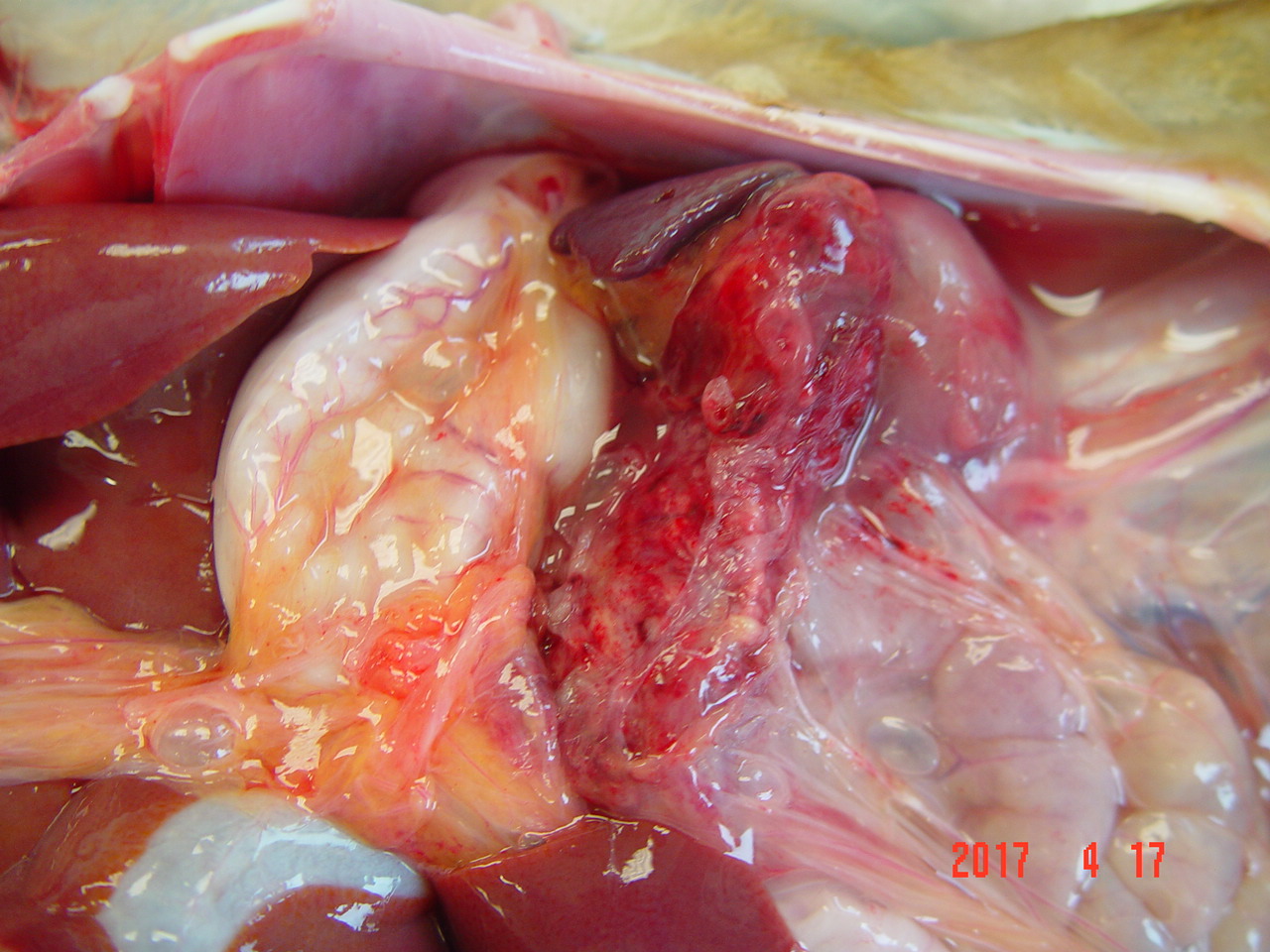

Gross Pathology: The abdomen contains 20-30 ml of blood-tinged fluid. The pancreas is enlarged (5.5 x 8 x 3 cm) and hemorrhagic (Fig 1). There is edema of the capsule of the left kidney and the serosa of the duodenum. Formed feces noted in the colon.

Laboratory results:

RBC Hgb Hct WBC PMN Eo Bas Mon Lym Plt Retic

- 5 months 5.18 12.1 39.1 8.55 41.6 1.6 0.2 7.1 49.5 404K 0

Presented 3.77 8.0 26.2 29.4 90.0 0 0 6.0 4.0 138K 10.3

Blood chemistry is unremarkable.

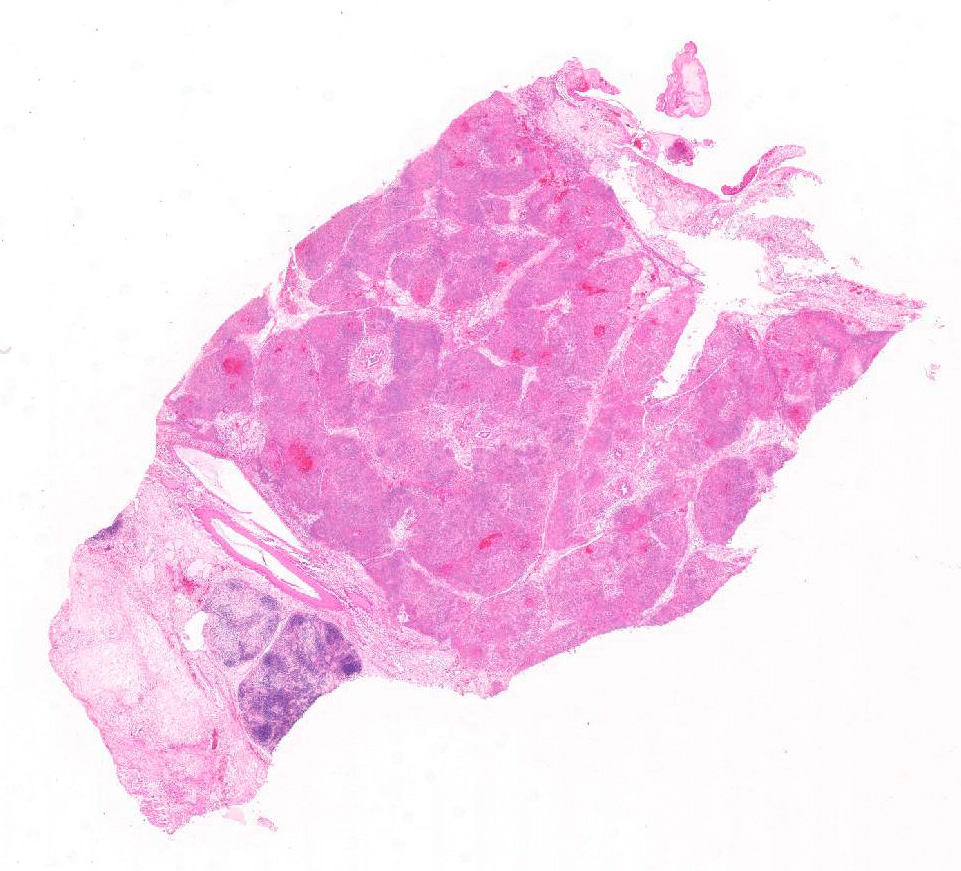

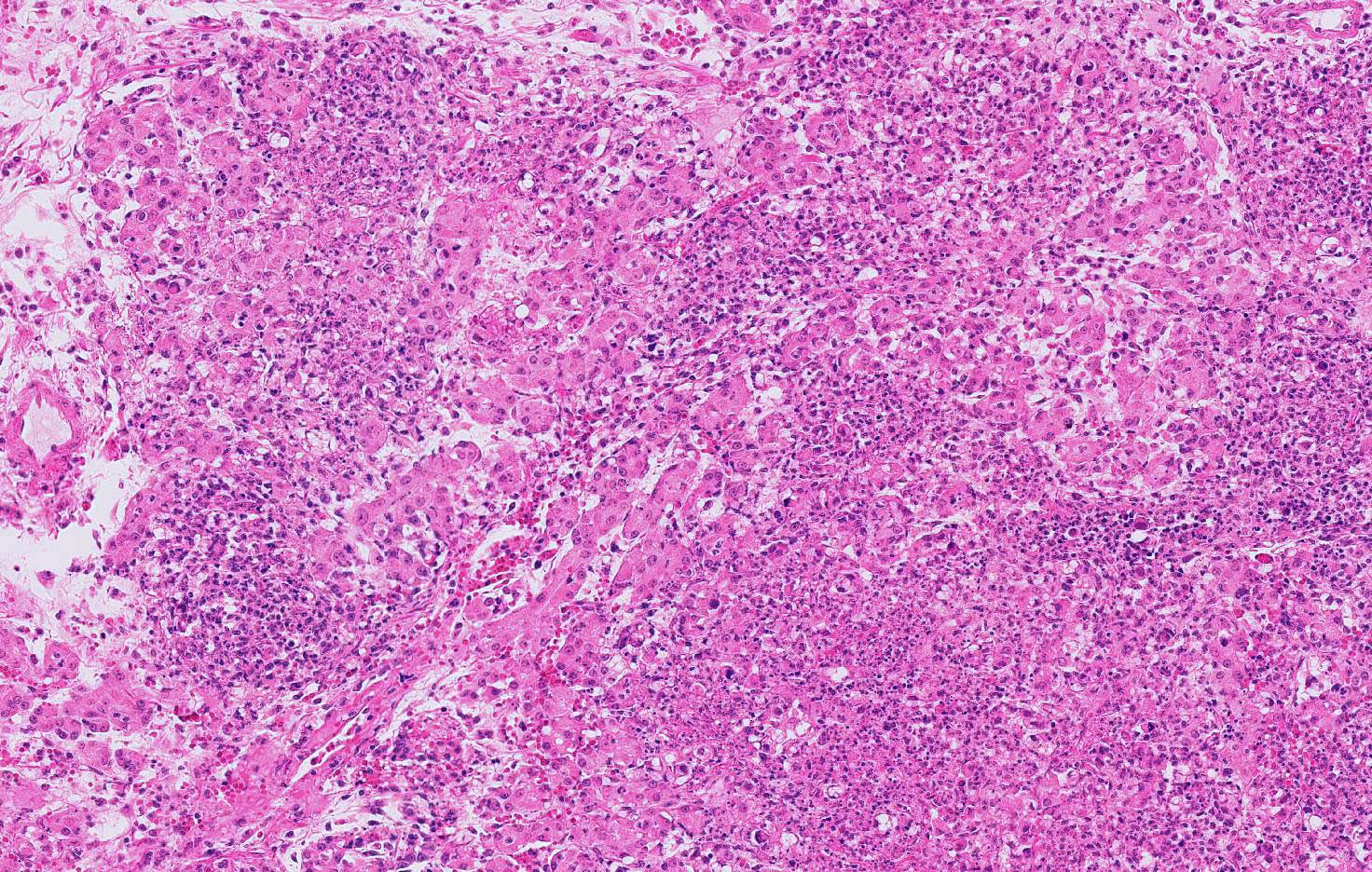

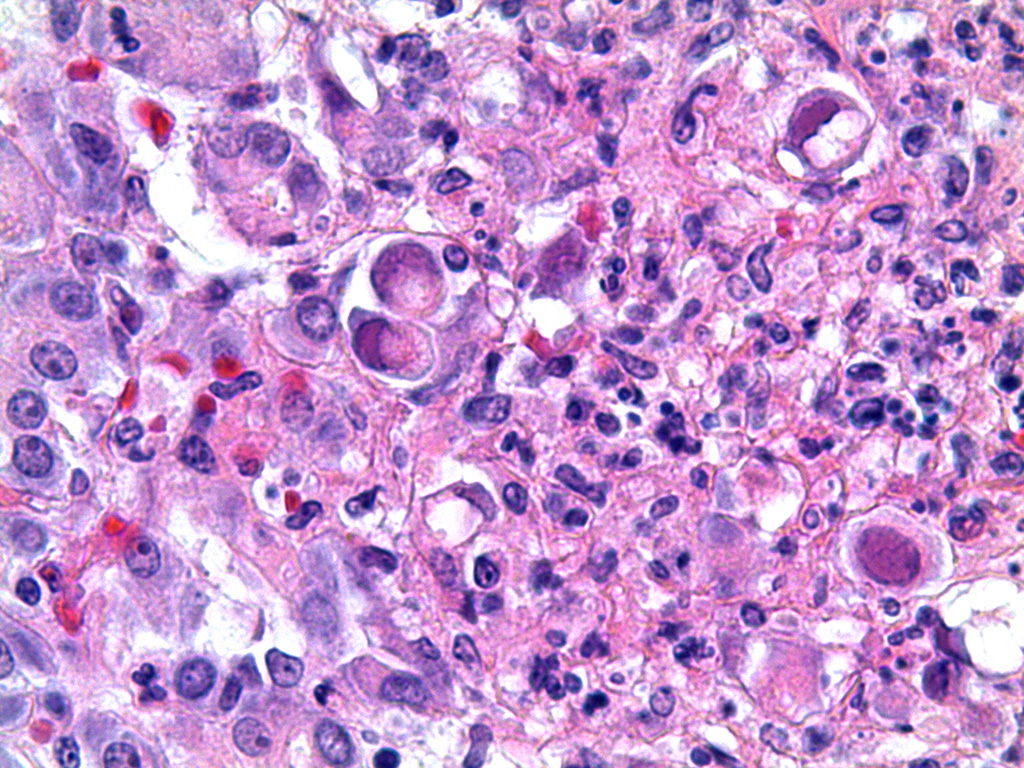

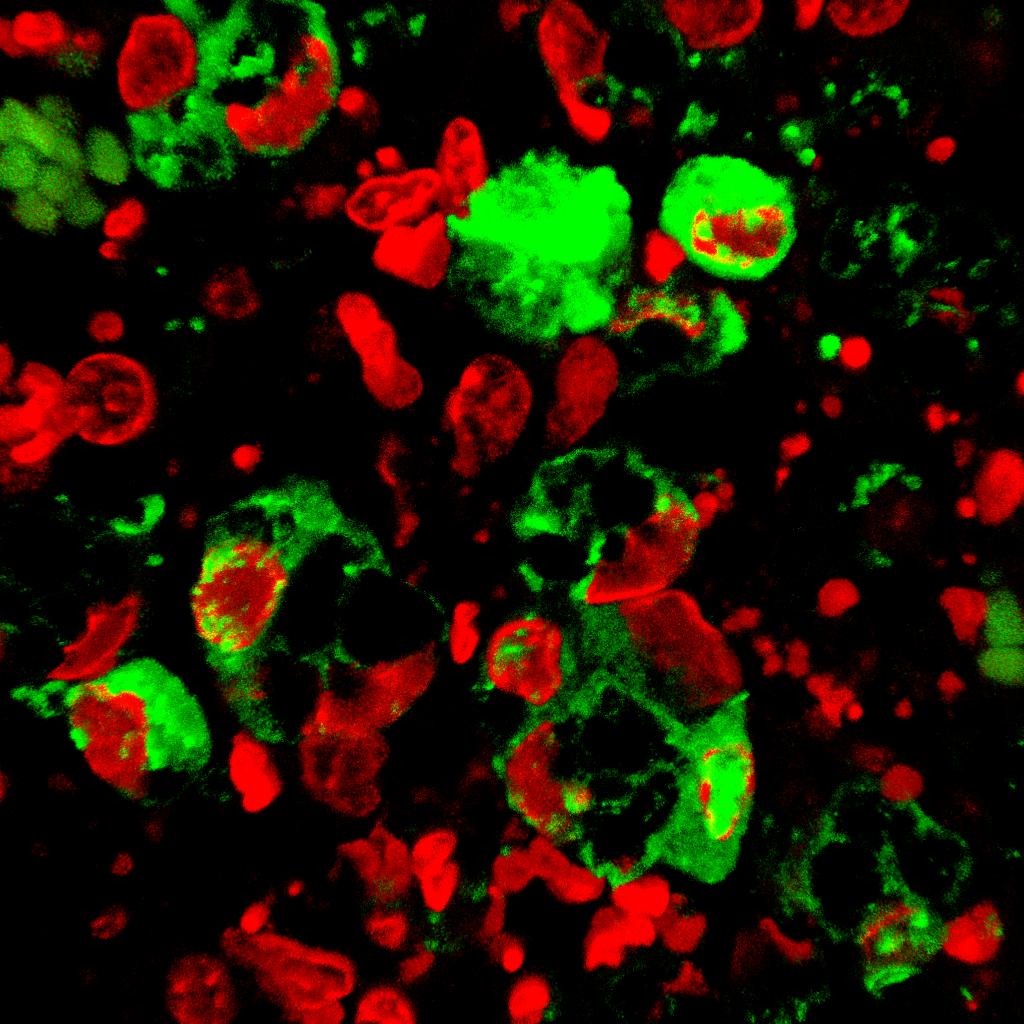

Microscopic Description: Pancreas: The capsule of the pancreas is edematous and diffusely hemorrhagic and infiltrated with numerous neutrophils and small numbers of eosinophils and macrophages. Fibrin tags containing neutrophils are attached to the peritoneal surface. Large zones of the acinar pancreas are necrotic with multifocal hemorrhage and infiltration of variable numbers of neutrophils and small numbers of macrophages. Some blood vessels contain fibrin thrombi; vascular walls contain segmental foci of degeneration with PMN infiltration or complete necrosis. Surviving epithelial cells are swollen and many contain slightly enlarged nuclei with marginated chromatin and glassy basophilic intranuclear inclusions. IFA staining with anti-adenoviral monoclonal antibody confirms the presence of adenovirus in epithelial cell nuclei and cytoplasm. Stroma is edematous.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Pancreas: Pancreatitis, acute hemorrhagic, necrotizing, Adenovirus with fibrinous peritonitis and necrotizing vasculitis.

Contributor’s Comment: Acute pancreatitis in humans is most often (80%) associated with biliary tract disease and alcoholism.5 Clinical signs include epigastric abdominal pain (80-95%), nausea and vomiting (40-80%), and abdominal distension (21-46%) with some displaying fever, jaundice, ascites, and pleural effusion.2 In most instances, gallstones and/or inflammation reduces outflow of digestive proenzymes, allows back-diffusion of these secretions across the pancreatic ducts, and activation of the proenzymes.5 High ethanol concentrations can induce spasm or edema of the sphincter of Oddi, as well as induce production of secretin from the small intestine triggering more pancreatic secretions.7 Protease inhibitors like alpha-1-antitrypsin, alpha-2-macroglobulin, c-1-esterase inhibitor, and pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor in body fluids and tissues protect against activation of nascent proenzymes stored and transported in membrane bound granules. However, protection is incomplete since, in the presence of calcium, trypsin bound to inhibitor still has some tryptic activity that activates other proenzymes.7 Damage to acinar cell membranes, ducts and blood vessels rapidly compounds the injury adding hemorrhage and anoxia.

Other causes of acute pancreatitis include drugs, hyperlipidemia, hypercalcemia, viral infections (mumps, coxsackievirus, hepatitis B, CMV, varicella, herpes simplex, adenovirus, HIV), bacterial and fungal infections (Mycoplasma, Legionella, Leptospira, Salmonella, Aspergillus, Toxoplasma, Cryptosporidium), vascular diseases, pregnancy and ascariasis.6 Drugs like the thiazide diuretics induce hypercalcemia; estrogens and HIV protease inhibitors induce hypertriglyceridemia with production of toxic free fatty acids, vascular damage and thrombosis.6 Blood and bone marrow transplantation have been linked to acute pancreatitis by a variety of mechanisms including drug toxicity, graft-versus-host-disease, and adenoviral infection.3

More specific to simian research, pancreatitis is rarely reported but half the cases are associated with adenovirus.4 We have found most adenoviral infections to be associated with SIV infection (91%) with 45% of these presenting with acute pancreatitis (unpublished). Adenoviral replication with movement of virus to the cytoplasm accounts for the extensive liver necrosis observed in chick embryos1 and given the large amounts of virus detected by IFA in the submitted case, in is not hard to speculate that cell lysis could easily overwhelm the protective inhibitors in tissue fluids.

Recent work with an acute pancreatitis mouse model induced by starvation has shown a critical role for small GTPase Rab7 in intracellular vesicle transport of lysosomes involved in autophagy and endocytosis.8 Pancreas-specific-Rab7-deficient mice exhibited enhanced disease due to blockade of endosome maturation suggesting that Rab7 may be a therapeutic target.

JPC Diagnosis: Pancreas: Pancreatitis, necrotizing, diffuse, severe with mild necrotizing steatitis and ductal and acinar intranuclear basophilic viral inclusion bodies, Indian rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), primate.

Conference Comment: Within the family Adenoviridae, of which there are numerous ubiquitous viruses that affect a wide number of species, the genus Mastadenovirus contains the human and nonhuman primate isolates. The name “adenovirus” is derived from adenoid, meaning the lymphoid tissue of the nasopharynx, because the first isolates were obtained from those locations in military recruits suffering from upper respiratory tract infections. There are over 50 serotypes of adenovirus that has been isolated from nonhuman primate species (macaques, African green monkeys, baboons, chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and cotton-topped tamarins), and they tend to cause respiratory or enteric disease in immune suppressed animals. In fact, adenoviruses have been isolated from healthy animals, suggesting that persistent infections are common.9

When on immunosuppressive drugs or infected concomitantly with immunosuppressive viruses (SIV and betaviruses) respiratory tract infections with adenovirus results in necrosis of epithelial cells of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli. The gastrointestinal tract is the second most common organ system infected, characterized microscopically by mucosal erosion or ulceration with necrotic enterocytes containing prominent adenoviral inclusions. There have been numerous reports of adenoviral-induced pancreatitis which seem to occur most frequently in young macaques, as in this case, that have been severely immunocompromised by SRV-1, SRV-2, and SIV.4 Even less common are necrotizing lesions of the liver, kidney, and urinary bladder which microscopically appear as necrotizing hepatitis, tubulointerstitial nephritis, and hemorrhagic cystitis with the aforementioned intranuclear inclusions. Although these inclusions are prominent in infected animals, they may resemble CMV and SV40 which also produce basophilic intranuclear inclusions, albeit resulting in significant nucleomegaly and cytomegaly.9

Conference participants commented on additional changes within these tissues. Within the remaining areas of intact pancreas (which were rare), there was evidence of acinar atrophy with cell shrinkage, loss of zymogen granules, and an overall increase in the acinar luminal size. , Vasculitis and thrombosis was identified in and away from areas of necrosis. In areas of necrosis, it was easier to attribute vascular necrosis to the ongoing devastation in the surrounding tissues. In areas away from the necrosis, participants searched for adenoviral inclusions within endothelium, but none were identified. Finally, participants identified changes within the adjacent pancreatic lymph node which included edema and increased numbers of neutrophils within cortical and medullary sinuses, but rather than suggest a separate necrotizing process in the lymph node, participants decided that the lymph node was simply draining the adjacent area of inflammation.

Contributing Institution:

Tulane National Primate Research Center

www.tulane.edu/tnprc/

References:

- Alemnesh W, Hair-Bejo M, Aini I, Omar AR. Pathogenicity of fowl adenovirus in specific pathogen free chicken embryos. J Comp Path. 2012;146:223-229.

- Bai HX, Lowe ME, Husian SZ. What have we learned about acute pancreatitis in children? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52(3):2262-270.

- Bateman CM, Kesson SM, Shaw PJ. Pancreatitis and adenoviral infection in children after blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2006;38:807-811.

- Chandler FW, McClure HM. Adenoviral pancreatitis in rhesus monkeys: current knowledge. Vet Pathol. 1982;Suppl 7:171-180.

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 1999:904-907.

- Hung WY, Lanfranco OA. Contemporary review of drug-induced pancreatitis: A different perspective. World J Gastointestinal Pathophys. 2014;5(4):405-415.

- Rubin E, Farber JL. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 1988:812-816.

- Takahashi K Mashima H, Miura K, Maeda D, Goto A, Goto T, Sun-Wada G, Wada Y, Ohnishi H. Disruption of small GTPase Raby exacerbates the severity of acute pancreatitis in experimental mouse models. Science Reports. 2017;7(2817):1-16.

- Wachtman L, Mansfield K. Viral diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. 2. Waltham, MA: Academic Press; 2012:27-30.