Signalment:

Gross Description:

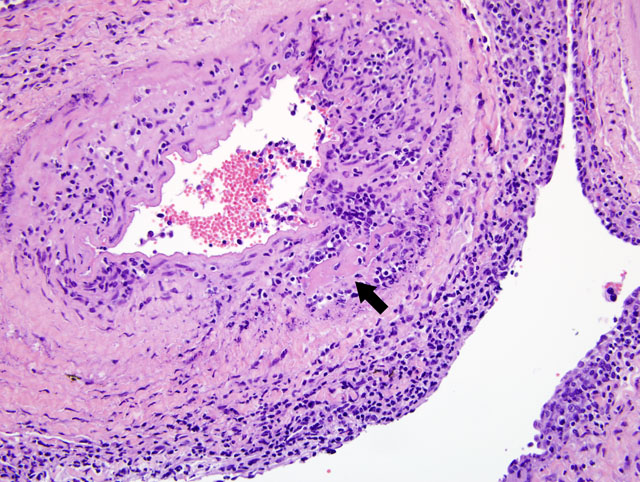

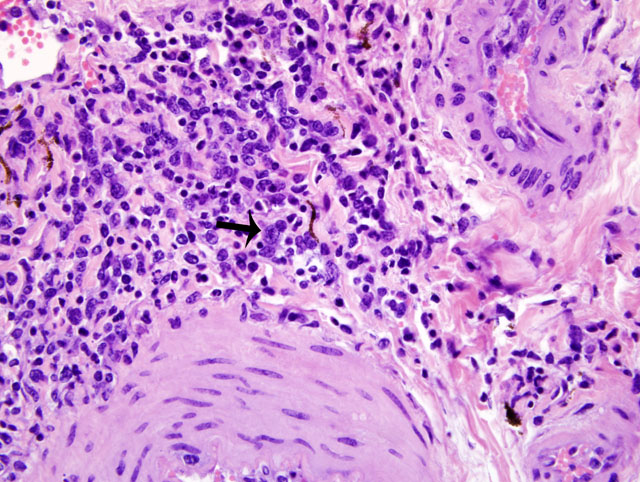

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

IFA positive for malignant catarrhal fever virus (lymph node)

PCR positive for AlHV-1 and OHV-2 malignant catarrhal fever viruses

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

MCF is a pansystemic lymphoproliferative disease syndrome of certain wild and domestic artiodactylid species, occurs worldwide, and is caused by several closely related members of the Rhadinovirus genus of gamma-herpes viruses that exist in nature in subclinical infections in carrier ruminants.(7) Although no clinicopathologic differences exist between the diseases, four viruses are associated with MCF: 1) Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 (AlHV-1) carried by wildebeest; 2) Ovine herpesvirus 2 (OHV-2) endemic in domestic sheep; 3) Caprine herpesvirus 2 (CpHv-2) endemic in domestic domestic goats; and 4) an undetermined virus in white-tailed deer (MCFV-WTD).(3,4) Unlike the alpha- and betaherpesvirus, the gammaherpesvirus appear to favor the establishment of latency over lytic replication in most infected cells of their natural hosts. In return for protecting their latently infected cells from immune system destruction, these reservoir hosts have evolved to being subclinical transmitters of the virus. However, a balance must exist between the immune response and the number of infected cells. Virus excretion is usually low and may occur constantly or intermittently. Animals targeted by the virus that did not co-evolve with it, as well as natural hosts with immune deficiencies, lose control over numbers of latently infected cells and develop lethal disease.(1)

First isolated and identified in 1960 from wildebeest, AlHV-1 is restricted to Africa and zoological collections where wildebeest are present.(5) OHV-2 occurs worldwide, but has never been isolated in cell culture. Natural infections can occur in goats, cattle, bison, deer, and pigs.(1,2) Clinical signs and prominent gross changes include lymphadenopathy, eyelid edema and conjunctivitis, corneal opacity and ulceration, hypopyon, oculonasal discharge, congestion of nasal mucosa, oral and esophageal erosion to ulceration, exudative dermatitis, sloughing of horns and hooves, and nervous signs. The primary microscopic lesions in ruminants with acute MCF are lymphoid proliferation and infiltration, necrotizing vasculitis with perivascular lymphoid infiltration, and necrosis of mucosal epithelium.(3,7) In situ, PCR and immunohistochemistry studies with OHV-2 have demonstrated that the predominating infiltrating cell type is the CD8+ T-lymphocyte and that large numbers are infected. Cases of MCF are generally sporadic and the disease is not contagious among cattle by direct contact, making them dead end hosts. The incubation period is usually 2-10 weeks, but may be much longer.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The most characteristic features of MCF are proliferation of CD8+ T-lymphocytes, vasculitis, and respiratory and gastrointestinal ulceration. The virus infects large granular lymphocytes which have T-suppressor cell and natural killer cell activity. Viral infection of these cells is thought to cause lymphoproliferation (due to suppressor dysfunction) and necrosis (due to natural killer cell dysfunction).(3) Disease progression can be as short as 1-3 days. This short clinical progression usually manifests as a hemorrhagic enteritis. Animals with less severe gastrointestinal disease often have neurologic disease combined with general debilitation and die within 10 days of disease onset.(3)

Grossly, MCF is characterized by mucosal ulceration in the upper portions of the respiratory tract, which coincides with the copious nasal discharge sometimes seen clinically. Skin lesions are often seen in sheep-associated MCF but are often overlooked during the post-mortem. Like rinderpest, esophageal erosions and ulcers are more common in the proximal third of the gastrointestinal tract. Ocular lesions include edema of the eyelids and conjunctiva and corneal opacity.(3)

The kidney may be mottled secondary to infarction or interstitial nonsuppurative nephritis. The urinary bladder can also be affected with lesions similar to those seen in the kidney, or the mucosa may be ulcerated causing hemorrhage and hematuria. As mentioned previously, lymph node as well as hemal node enlargement is prominent as a result of lymphoid hyperplasia. The spleen also contains prominent lymphoid follicles. Neurologic disease is common in subacute and chronic cases and is secondary to vasculitis.(3)

References:

2. Albini S, Zimmerman W, Neff F, Ehlers B, HaniH, Li H, Hussy D, Engels M, Ackermann M: Identification and quantification of ovine gammherpesvirus 2 DNA in fresh and stored tissues of pigs with symptoms of porcine malignant catarrhal fever. J Clin Micro 42:900-904, 2003

3. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK: The Alimentary System.Â

4. Li H, Dyer N, Keller J, Crawford TB: Newly recognized herpesvirus causing malignant catarrhal fever in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Clin Micro 38:1313-1318, 2000

5. Li H, Gailbreath K, Bender LC, West K, Keller J, Crawford TB: Evidence of three new members of malignant catarrhal fever virus group in muskox (Ovibos moschatus), Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana), and Gemsbok (Oryx gazelle). J Wild Dis 39:875-880, 2003

6. Li H, Keller J, Knowles DP, Crawford TB: Recognition of another member of the malignant catarrhal fever virus group: an endemic gammaherpesvirus in domestic goats. J Gen Virol 82:227-232, 2001

7. Simon S, Li H, OToole D, Crawford TB, Oaks JL: The vascular lesions of a cow and bison with sheep-associated malignant catarrhal fever contain ovine herpesvirus 2-infected CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Gen Virol 84:2009-2013, 2003