Signalment:

Gross Description:

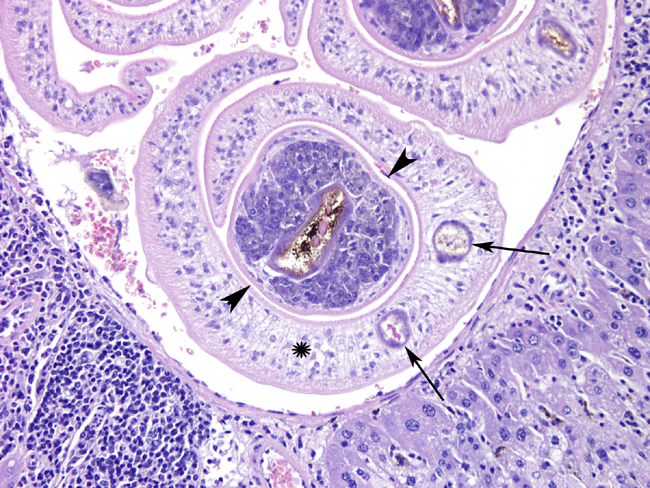

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Life cycle3: Only the cercarcial stage released by freshwater snails is infectious to humans. A schistosome miracidium hatched from an egg in the water penetrates a snail and multiplies into many cercariae, which escape back into the water. The cercariae penetrate the skin of the definitive host and then develop into schistosomules, which migrate into blood vessels and travel to the lungs. After a week, the schistosomules migrate to the liver and hepatic portal venules, where sexual maturity and pairing occurs. The adults travel to mesenteric venules, where S. mansoni eggs penetrate the vessel walls and pass through the wall of the intestine into the feces. Many embryonated eggs remain in body tissues. Eggs released in mesenteric venules can be carried in the intrahepatic portal system where they lodge in the hepatic sinusoids and provoke granulomas.Â

Human Disease3: In humans, symptoms of acute infection include fever, cough, asthma, hive, and diarrhea with marked eosinophilia. Hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy can occur. After the initial reaction to the eggs released by the parasites, immune downregulation can decrease these signs. In chronic infections, granulomas (eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells) occur around eggs, often with subsequent fibrosis. Symmers pipestem fibrosis is seen grossly as tracts of portal fibrosis resembling white clay pipestems throughout the tissue, which contributes to portal hypertension and often occurs in patients that lack a downregulation of the immune response. Adult schistosomes in veins do not evoke a host response, but there can be significant reaction to dead worms following treatment or late stages of infection. Glomerulonephritis can also occur, probably due to immune complexes. Colonic polyps containing many schistosome eggs and adults can occur with S. mansoni and S. haematobium infections. Bilharziomas in the intestinal serosa and mesentery containing fibrous and inflammation around masses of eggs can develop. Cardiopulmonary changes can include pulmonary arteritis and cor pulmonale. Schistosome eggs can also enter the meninges and spinal cord causing meningitis and myelitis. Dermatitis and rashes can occur to the schistosomules. S. haematobium causes urogenital schistosomiasis.Â

Mouse Model of Schistosomiasis7: The mouse is a widely used model of experimental schistosomiasis. Mice are usually infected percutaneously through the tail or abdomen by exposure to cercaria in water or can be injected subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with cercaria5. Infected mice develop hepatic granulomas and immunoregulatory responses similar to humans. Somular antigens that cross-react with schistosomal egg antigens (SEA) induce T-lymphocyte activation and TM/E cell expansion. Hepatic granulomas develop as a delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response by SEA-reactive CD4+ (__+) MHC-II-dependent T cells. Other cells present in the granulomas included CD8+ T cells, B cells, eosinophils, mast cells, NK cells, basophils, macrophages, neutrophils, __+, and fibrocytes. Mice develop granulomas in the liver, colon, and Peyers patches, which begin to decrease in size about 8 weeks post infection due to downregulation of the immune response. Hepatic granuloma size was controlled by both TH1 and TH2 responses: TH1 cytokines (IL-2, IFN-_), TH1 cytokine receptor (IFN-_), TH2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, TNF-_), and a TH2 cytokine receptor (IL-4_). Fibrosis was associated with IL-4 and TGF-_, and was independent of the regulation of the hepatic granulomas.Â

Parasite description3,4: Schistosomes are unique from other trematodes infecting humans in that they live in blood vessels, they have separate sexes (most trematodes are hermaphroditic), the eggs are nonoperculated, and the metacercariae are not encysted. Anatomical features of mature schistosomes include an oral and ventral sucker at the anterior end, the lack of a body cavity, a brown granular schistosomal pigment often found in the parasites cecum, tegmental tuberculations in male S. mansoni males, and a gynecophoral canal in males which holds the female. S. mansoni eggs are 114-175 _m by 45-68 _m and have a lateral spine.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The three genera that make up this family include Schistosoma, Heterobilharzia and Orientobilharzia. Schistosomatidae of veterinary importance include Heterobilharzia americana in mammals of the southern USA, as well as Orientobilharzia turkestanicum, O. dattai and O. bomfordi in Asia. Other Schistosomatidae are separated into four groups depending on egg morphology and intermediate snail hosts.6

- S. haematobium group

- S. bovis southern Europe, tropical Africa and Asia; portal and mesenteric veins (ruminants, horses, camels, pigs)

- S. mattheei central and southern Africa; stomach, urogenital, portal and mesenteric veins (ruminants)

- S. curassoni west Africa (ruminants)

- S. leiperi central Africa (artiodactyls)

- S. mansoni group central Africa

- S. rodhaini (dogs, carnivores)

- S. indicum group India and southeast Asia

- S. spindale mesenteric veins (ruminents, horses, dogs)

- S. nasale nasal mucosal veins (cattle, goats, horses)

- S. indicum portal and mesenteric veins (herbivores)

- S. incognitum (swine, dogs)

- S. japonicum group Far East

- S. japonicum (human, domestic animals)

- S. mekongi (dogs, humans)

Morphological characteristics of trematodes include a digestive tract and no body cavity.4 Schistosome eggs contain a miricidium, a lateral spine, and have no operculum.3

This case was reviewed in consultation with Dr. Chris Gardiner, AFIP consultant in veterinary parasitology. We are grateful to Dr. Gardiner for his comments and advice on this interesting case.

References:

2. Anderson WI, King JM, Uhl EM, Hornbuckle WE, Tennant BC: Pathology of experimental Schistosoma mansoni infection in the Eastern Woodchuck (Marmota monax). Vet Pathol 28:245-247, 1991

3. Cheever A, Neafie RC: Schistosomiasis. In: Pathology of Infectious Diseases, ed. Meyers WM, vol.1, pp. 23-47. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and American Registry of Pathology, 2000

4. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL: Morphological characteristics of trematodes in tissue section. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. pp. 46-49. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C., 2006

5. Lewis F: Schistosomiasis. In: Current Protocols in Immunology, pp. 19.1.1-19.1.28. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, 1998

6. Maxie MG, Robinson WF: Cardiovascular system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 95-97. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

7. Stavitsky AB: Regulation of granulomatous inflammation in experimental models of schistosomiasis. Infect Immun 72:1-12, 2004