WSC 22-23

Conference 21

Case II:

Signalment:

7-month-old, female spayed, boxer dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The patient presented to their veterinarian for a 3-month history of pollakiuria characterized by voiding small volumes of urine every 30-60 minutes. Cystocentesis of the patient’s bladder yielded small quantities of foul-smelling urine which upon urinalysis, contained markedly increased numbers of leukocytes (pyuria) and erythrocytes (hematuria). Aerobic bacterial culture of the urine isolated large numbers of Escherichia coli. Despite antibiotic therapy for several weeks, pollakiuria persisted. Ultrasonographic and radiographic assessment of the urinary bladder revealed a severely and irregularly thickened bladder mucosa; there was no overt evidence of cystoliths. An incisional biopsy of the urinary bladder was taken and submitted for histopathology.

Gross Pathology:

The bladder mucosa was markedly thickened by multifocal-to-coalescing, poorly demarcated, firm, pale tan, polypoid masses.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory results reported.

Microscopic Description:

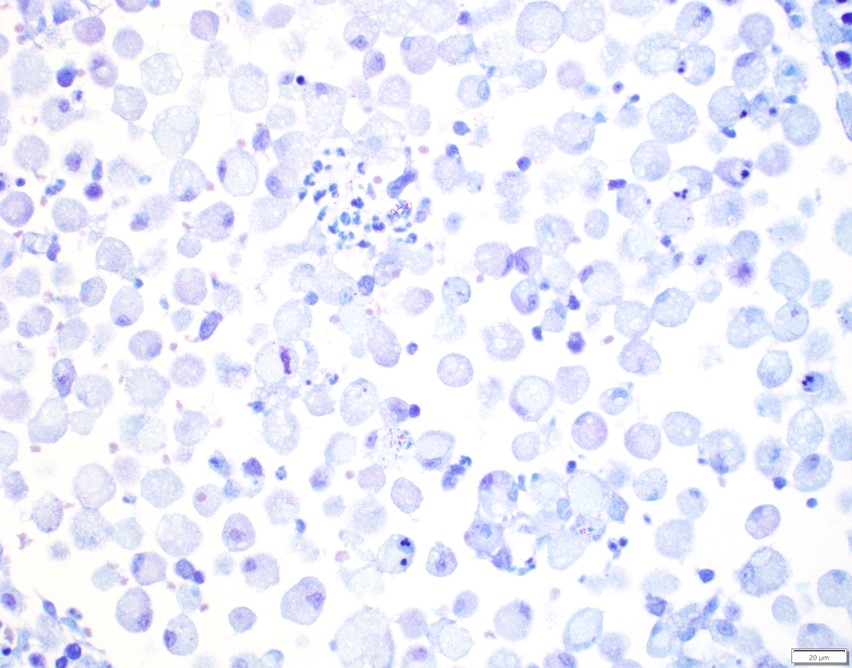

Urinary bladder: Expanding the superficial aspect of the urinary bladder lamina propria and elevating the overlying urothelium is a large, poorly demarcated, densely cellular, plaque-like mass composed of dense sheets of large macrophages. These large macrophages have abundant cytoplasms that are packed with innumerable coarse eosinophilic granules and frequently contain one to three, 5-15 μm, pale eosinophilic, finely granular intracytoplasmic inclusions. Multifocally scattered throughout the dense sheets of macrophages are small aggregates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. The urothelium overlying the mass is multifocally eroded and has small-to-moderate numbers of lymphocytes and neutrophils percolating throughout. The lamina propria underlying the mass is moderately expanded by clear to pale eosinophilic wispy fluid (edema).

The intracytoplasmic granules and inclusions within the macrophages are all strongly PAS-positive. The granules and inclusions do not stain positively with Toluidine blue, Luxol fast blue, Giemsa, Von Kossa, or Prussian blue stains. There is no overt evidence of acid-fast organisms within these macrophages upon application of Ziehl-Neelsen and Fite-Faraco stains.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Urinary bladder: Severe, locally extensive, chronic, granulomatous cystitis with myriad intracytoplasmic PAS-positive granules and inclusions, lamina propria edema, and multifocal epithelial erosion

Contributor’s Comment:

Histopathology of the submitted urinary bladder mass revealed expansion of the lamina propria by a large plaque-like aggregate of large macrophages filled with abundant intracytoplasmic PAS-positive granules and inclusions. These microscopic findings, when viewed in conjunction with the signalment of the patient and the submitted clinical history, were deemed most consistent with a diagnosis of malakoplakia. Granular cell tumor and mycobacteriosis were also considered differential diagnoses prior to positive immunohistochemistry results for Iba1 (discounting a granular cell tumor) and the absence of overt acid-fast organism upon application of additional histochemical stains (discounting mycobacteriosis).

Malakoplakia is an uncommon granulomatous disease that has been reported in several veterinary species including dogs2,3,6,123 cats1,4,10, pigs7,14, and a Cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis)11. Malakoplakia typically manifests within the genitourinary tract (particularly the urinary bladder) but has been reported in a variety of other body systems7,14,15. In humans, most cases of malakoplakia occur in middle-aged women, with infrequent cases reported in children15. In the seven previously reported cases of malakoplakia in dogs, all seven cases occurred in females with ages ranging from 6-weeks-old to 8-months-old2,3,6,13. In all of the other spontaneously occurring veterinary cases in which the full signalment was reported, all animals were female4,9,14.

While the exact etiopathogenesis of malakoplakia is still unclear, it has been putatively associated with recurrent bacterial infections, with the most commonly isolated bacteria being E. coli (as in the present case)15. It is postulated that females are over-represented in the current literature as they are more susceptible to urinary tract infections than males 5. Immunosuppression has also been implicated as a contributing factor in the development of this disease as many human patients with malakoplakia are ailed by concurrent conditions that debilitate the immune system (e.g. acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and neoplasia) or are receiving immunosuppressive therapy15.

Grossly, malakoplakia appears as firm tan to yellow-brown masses that vary in morphology from focal plaques to multifocal-to-coalescing nodules to locally extensive thickenings of the affected organ(s). The typical histological appearance of malakoplakia is exuberant granulomatous inflammation characterized by dense sheets of large macrophages filled with abundant intracytoplasmic PAS-positive granules and inclusions (so-called ‘von Hansemann-type macrophages’)15. Many have postulated that the PAS-positive granules and inclusions within these macrophages are the result of defective macrophage phagolysosome function and subsequent accumulation of bacterial breakdown products within the cytoplasm15. While not present in all cases, small numbers of 3-8 μm basophilic intracellular and/or extracellular targetoid concretions termed ‘Michaelis-Gutmann bodies’ are scattered throughout regions of granulomatous inflammation; these concretions are thought to be pathognomonic for malakoplakia9. ‘Michaelis-Gutmann bodies’ stain positively with both Von Kossa and Prussian blue stains and are postulated to represent concretions of organic matter, iron, and calcium derived from bacterial breakdown products9. Von Kossa and Prussian blue stains did not highlight the presence of ‘Michaelis-Gutmann bodies’ in the present case.

The histological appearance of the macrophages within malakoplakia lesions are strikingly similar to those found in cases of granulomatous colitis of boxer dogs (GCB; also known as histiocytic ulcerative colitis. GCB, similar to malakoplakia, is also associated with an exuberant granulomatous inflammatory response to E. coli11. It is salient to note that all seven reported cases of malakoplakia in dogs (including the present case) occurred in brachycephalic breeds that have been known to develop GCB (Boxer, Pug, English Bulldogs, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and French Bulldog) 2,3,6,13. The similarities between GCB and malakoplakia are intriguing and certainly strengthen the hypothesis that malakoplakia may arise in individuals that possess macrophages that are unable to eliminate certain E. coli pathotypes, resulting in persistent infections and macrophages becoming laden with PAS-positive bacterial products.

In summary, malakoplakia is an uncommon granulomatous disease that typically affects the genitourinary tract. Females, brachycephalic dog breeds, and young animals are over-represented in cases of malakoplakia within the current veterinary literature. While the exact etiopathogenesis of malakoplakia is unclear, both bacterial infection (namely E. coli) and immunosuppression are putatively associated with the development of this disease. Given the various similarities between malakoplakia and granulomatous colitis of boxer dogs (GCB), a genetic deficit that renders macrophages unable to eliminate certain E. coli pathotypes may also be involved in the development of malakoplakia. Malakoplakia should be considered a differential diagnosis for urinary bladder masses, especially in young female dogs with a history of bacterial cystitis.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Biomedical Sciences, Section of Anatomic Pathology

College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University

Ithaca, NY

USA

https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments/biomedical-sciences/section-anatomic-pathology

JPC Diagnosis:

Urinary bladder, lamina propria: Cystitis, granulomatous, diffuse, severe.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent comment on this uncommon condition in humans and select animal species. The term malakoplakia is derived from the Greek words for soft (malacos) and plaques (placos). The condition was first described by Michaelis, Gutmann, and von Hansemann in 1902-1903, and the key histologic features of this condition still bear their names.8 Malakoplakia occurs more commonly in humans than in animals, though it is still rare. In humans, the condition has been documented in the urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, gall bladder, pancreas, skin, reproductive tract (prostate, testes, cervix, vulva), lungs, and other tissues.15 In the gastrointestinal system, the most commonly affected sites are the colon and rectum, and its occurrence in the colon has been associated with colon cancer.15 Cutaneous malakoplakia more commonly occurs in adult males and in organ transplant recipients on an immunosuppressive regimen.8 Cutaneous lesions may present as papules, nodules, ulcers, or abscesses with draining tracts; occasionally, cutaneous lesions are associated with nonhealing surgical wounds.8 While E. coli is the most commonly isolated organism in humans, certain types of patients may be prone to developing malakoplakia with a different organism. Rhodococcus equi, for instance, is commonly found in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.15

References:

- Bayley C, Slocombe R, Tatarczuch L. Malakoplakia in the urinary bladder of a kitten. J Comp Pathol. 2008;139(1):47-50.

- Benzimra C, Job C, Pascal Q, Bureau S, Combes A, Bongrand Y, R. Faucher M. Malakoplakia of the bladder in a 4-month-old puppy. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2019;55(5):261-5.

- Brückner M. Malakoplakia of the urinary bladder in a young French Bulldog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;260(5):543-8.

- Cattin RP, Hardcastle MR, Simpson KW. Successful treatment of vaginal malakoplakia in a young cat. J Feline Med Surg Open Rep. 2016;2(2). doi:10.1177/2055116916674871

- Cianciolo RE, Mohr FC. Urinary system. In: Maxie GM, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, & Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2015:459-461.

- Davis KL, Cheng L, Ramos-Vara J, Sánchez MD, Wilkes RP, Sola MF. Malakoplakia in the urinary bladder of 4 puppies. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(4):699-704.

- Gelmetti D, Gibelli L, Gelmini L, Sironi G. Malakoplakia with digestive tract involvement in a pig. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(4):809-11.

- Kohl SK, Hans CP. Cutaneous Malakoplakia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008; 132: 113-117.

- Lewin KJ, Fair WR, Steigbigel RT, Winberg CD, Droller MJ. Clinical and laboratory studies into the pathogenesis of malacoplakia. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29(4):354-63.

- Rutland BE, Nimmo J, Goldsworthy M, Simcock JO, Simpson KW, Kuntz CA. Successful treatment of malakoplakia of the bladder in a kitten. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15(8):744-8.

- Simpson KW, Dogan B, Rishniw M, Goldstein RE, Klaessig S, McDonough PL, German AJ, Yates RM, Russell DG, Johnson SE, Berg DE. Adherent and invasive Escherichia coli is associated with granulomatous colitis in boxer dogs. Infect Immun. 2006;74(8):4778-92.

- Taketa Y, Inomata A, Sonoda J, Hayakawa K, Nakano-Ito K, Ohta E, Seki Y, Goto A, Hosokawa S. Granulomatous nephritis consistent with malakoplakia in a cynomolgus monkey. J Toxicol Pathol. 2013;26(4):419-22.

- Tang KM, Serpa PB, Santos AP. What is your diagnosis? Urine from a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. doi:10.1111/vcp.13139.

- Taniyama H, Ono T, Matsui T. Systemic malacoplakia in a breeding pig. J Comp Pathol. 1985;95(1):79-85. (9)

- Yousef GM, Naghibi B. Malakoplakia outside the urinary tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(2):297-300. (11)