Signalment:

Gross Description:

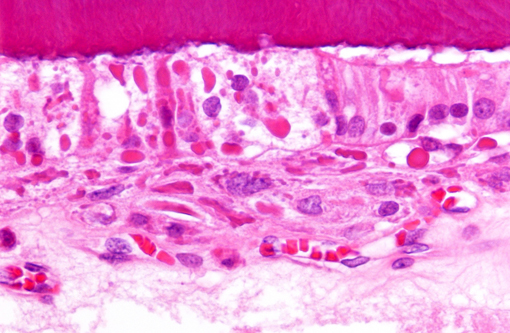

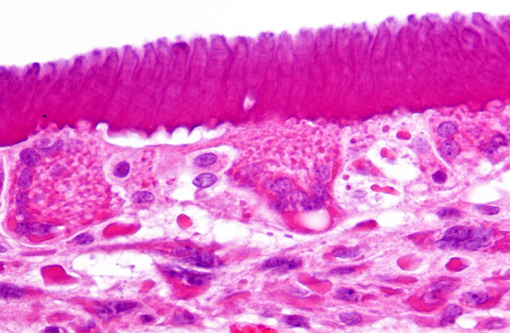

Histopathologic Description:

Findings in other tissues (not submitted) include necrosuppurative bronchopneumonia, demyelination of cerebellum and brain stem, neuronal degeneration and necrosis of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal cord segments, myocardial degeneration and necrosis, and lymphoid depletion of the spleen, lymph nodes and tonsils. Similar inclusions were present in the respiratory epithelium of the lung and trachea, mucosal epithelium of the renal pelvis and urinary bladder, astrocytes of the cerebrum and cerebellum and neurons of the spinal cord.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Transmission of CDV occurs via nasal or oral routes where the virus replicates immediately in the lymphoid tissue causing marked immunosuppression.(1,3,6) Depending on the host response, age and virus strain, the animal will either clear the infection or develop systemic disease. The virus has a propensity to infect epithelial cells in various organs, especially the central nervous system.(3,6) Dogs with partial immunity can be viremic and shed virus for an extended period of time in secretions; clinical signs in these animals are minor to absent and can later manifest as hyperkeratosis of the foot pad and nose.(3,6) Disease following vaccination with modified live CDV vaccine has been occasionally reported;(3,6) however, widespread use of prophylactic vaccination has successfully controlled the disease and is currently uncommon in vaccinated dog populations.(3) A rare condition caused by CDV infection in mature vaccinated dogs is a progressive chronic encephalomyelitis known as old dog encephalitis.(1,3,6)

Clinical signs manifest as respiratory, neurologic, and/or enteric disease. Less commonly, young dogs can develop dental lesions, ocular lesions, and neonatal myocardial degeneration and necrosis.(3) Dental lesions following infection may include necrosis and cystic degeneration of ameloblasts, formation of syncytia, disorganization of ameloblasts, and prominent eosinophilic cytoplasmic viral inclusions.(3,5) Delayed changes in the enamel occur in animals that survive infection and are described as focal defects in the enamel, which appear as depressions (pits) or well-delineated areas of hypoplasia.(3,4) This occurs because the virus directly infects ameloblasts and causes disruption of enamel formation.(4) Other dental abnormalities attributed to CDV include dental impaction, partial eruption, and oligodontia.(2) In the present case, the puppy was euthanized before gross or microscopic evidence of enamel hypoplasia could be detected.Â

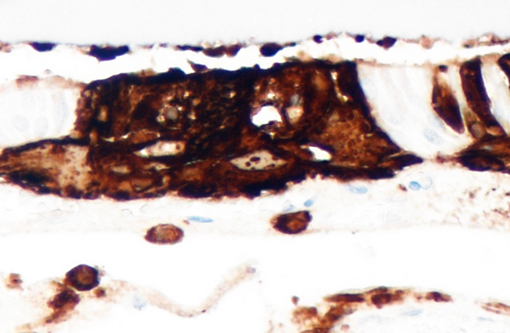

CDV can be diagnosed by a variety of methods; however, molecular assays such as reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and real-time RT-PCR are considered sensitive and specific.(6) Distinction between field and vaccine strains is possible via nested RT-PCR assays. Postmortem diagnosis is achieved when there is evidence of systemic or CNS disease and the presence of characteristic inclusion bodies supported by positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) or other ancillary tests. Ameloblasts in the present case had intense multifocal cytoplasmic staining for CDV, which correlated with histologic findings. Additionally, cerebrum and brainstem were IHC positive for CDV. In this case, an unequivocal diagnosis of CDV was made due to the spectrum of gross and microscopic lesions seen along with CDV positive ameloblasts and the reported clinical history.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a thorough review of the pathology of canine distemper virus. In addition to canine distemper, measles and rinderpest virus, the genus Morbillivirus comprises peste-des-petits-ruminants virus of goats and sheep, dolphin/porpoise morbillivirus, and phocine distemper virus.(1) Canine distemper virus has a broad host range; besides canids, infection has also been demonstrated in mustelids (ferrets, mink), raccoons, collared peccaries, non-human primates, seals, and felids, including lions, tigers, lynx, bobcat and even domestic cats.(1,6,7)

The signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) is a receptor used by morbilliviruses to invade immune cells.(7) Variations in species specificity and infection of aberrant species with canine distemper virus was historically thought to result from amino acid alterations in SLAM and/or the hemagglutinin (HA) protein that binds SLAM; however, recent studies suggest that variability of the hemagglutinin protein is less important in determining infectivity and pathogenicity in various host species than was previously believed. Regardless, CDV has emerged as a potentially devastating pathogen in certain wild felid populations.(7)

Although morbilliviruses are notable for producing both intracytoplasmic and intranuclear viral inclusions, conference participants observed that, in this case, intranuclear inclusions were poorly discernible, possibly as a result of the decalcification process.

References:

2. Bittegeko SB, Arnbjerg J, Nkya R, Tevik A. Multiple dental developmental abnormalities following canine distemper infection. J Am Animal Hospital Assoc. 1995;31:42-45.

3. Caswell JL Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:635-638.

4. Dubielzig RR. The effect of canine distemper virus on the ameloblastic layer of the developing tooth. Vet Pathol. 1979;16:268-270.Â

5. Dubielzig RR, Higgins RJ, Krakowka S. Lesions of the enamel organ of developing dog teeth following experimental inoculation of gnotobiotic puppies with canine distemper virus. Vet Pathol. 1981;18:684-689.Â

6. Martella V. Canine distemper virus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2008;38:787-797.Â

7. Terio KA, Craft ME. Canine distemper virus (CDV) in another big cat: should CDV be renamed carnivore distemper virus? MBio. 2013;4(5):e00702-13.