Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 2, Case 1

Signalment:

15 years, castrated male, domestic shorthair cat, Felis catus, feline.

History:

1-2 days’ retching, vomiting, diarrhea.

Gross Pathology:

The surgeon noted that the intestinal wall was subjectively thickened and the mesenteric lymph nodes were prominent.

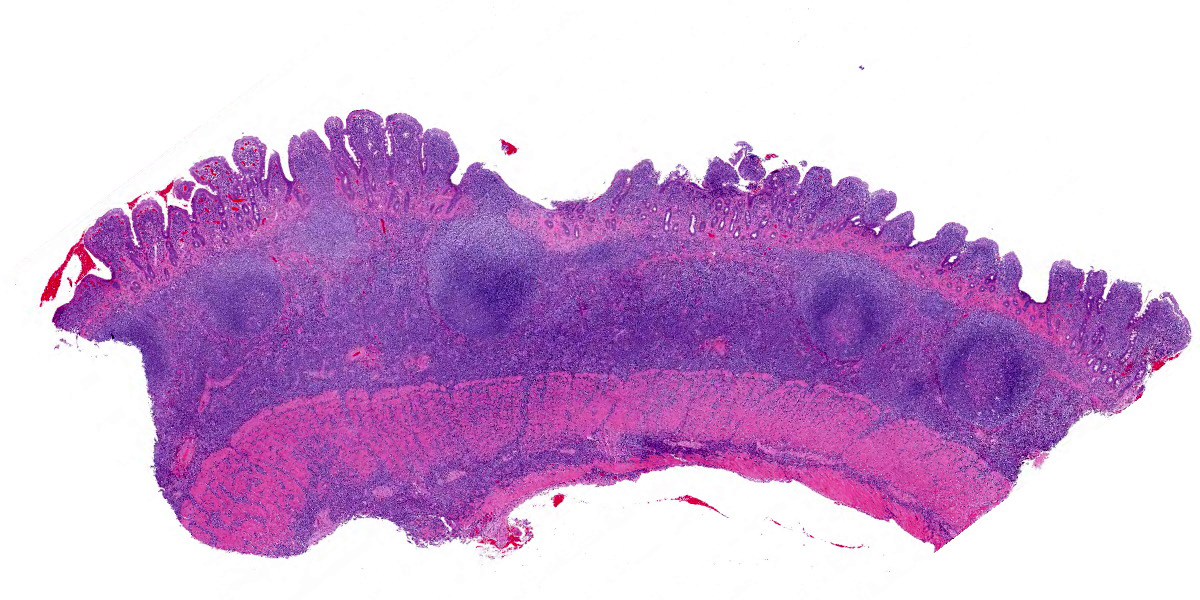

Microscopic Description:

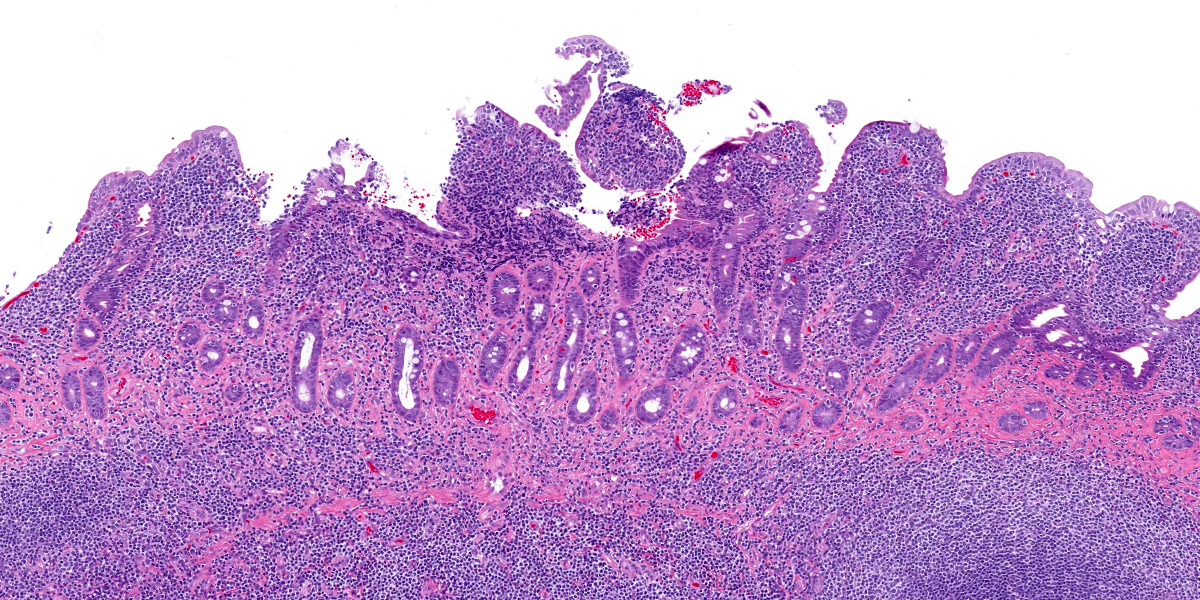

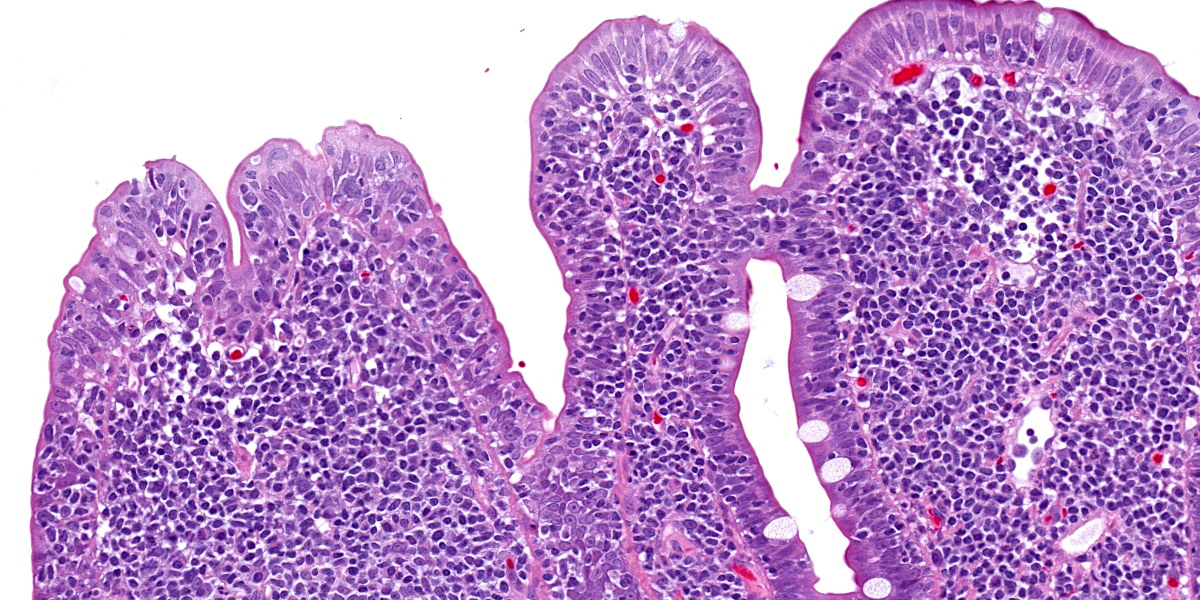

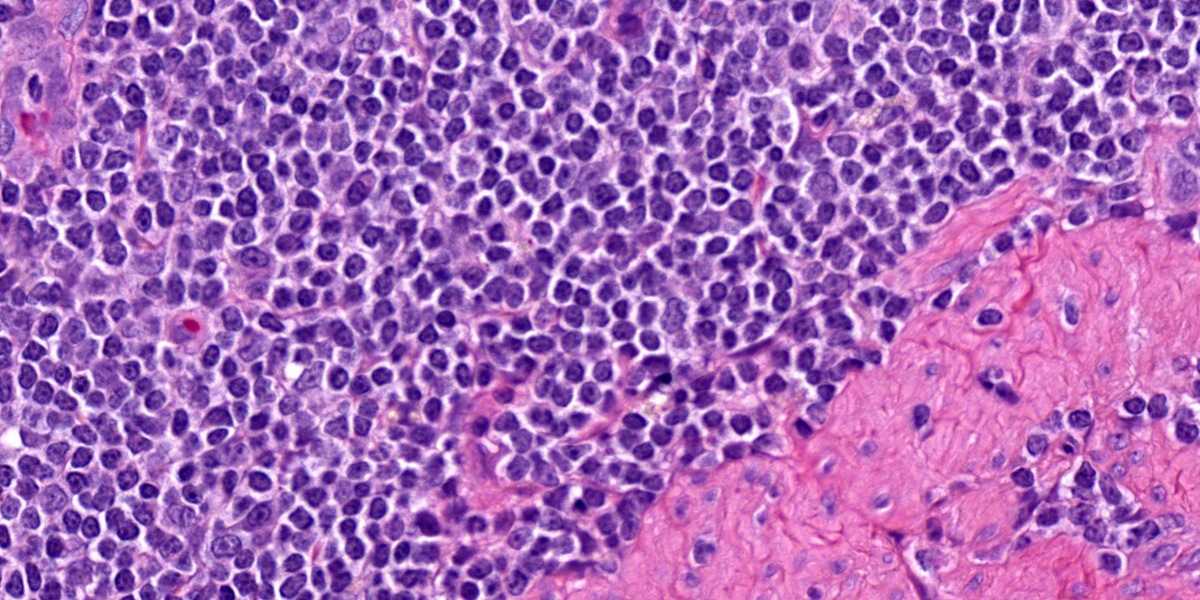

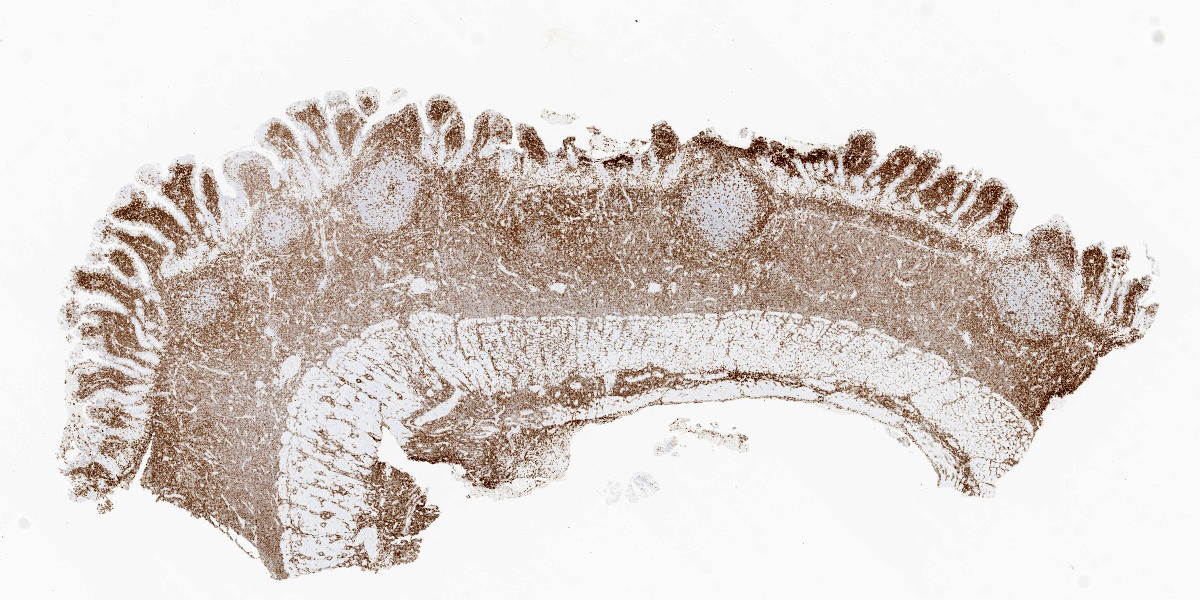

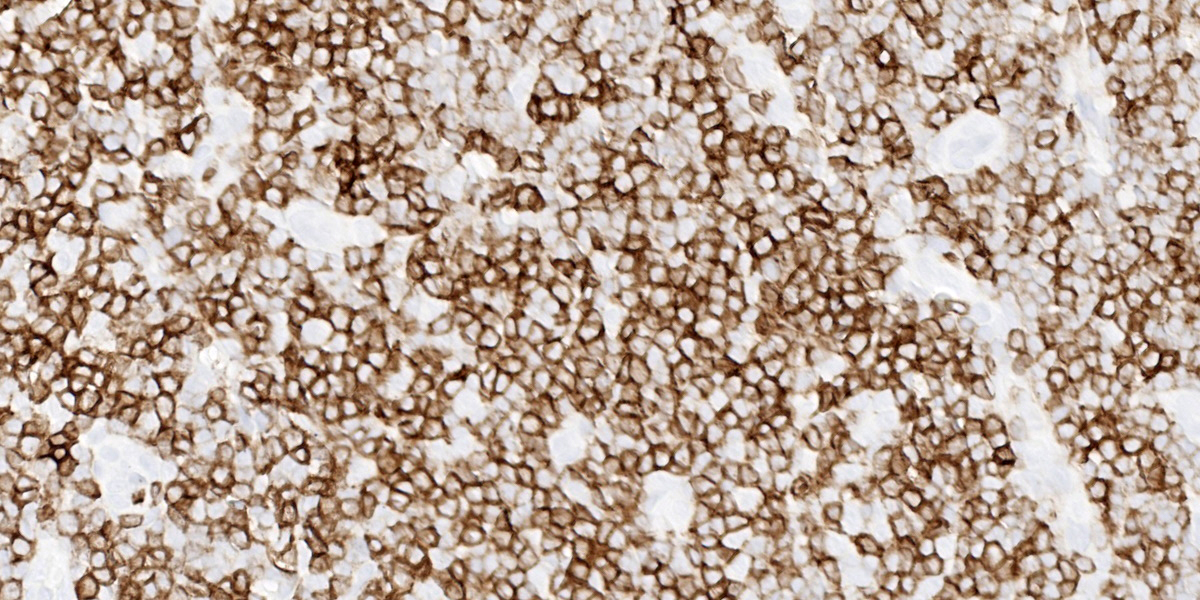

Five specimens, per submitter quadrate liver lobe, stomach, jejunum, mesenteric lymph node, and cecum, are bisected and embedded en toto in blocks 1-5, respectively. The major lesions are in the jejunal specimen (submitted slide 3), which has diffuse heavy mucosal infiltration by neoplastic lymphocytes with extension into the submucosa and multifocally along the vasculature into and through the tunica muscularis. A few lymphoid follicles with normal polarity remain in the submucosa. In the mucosa, epitheliotropism is prominent (indicating a T-lymphocyte population) with individual, clusters, and plaques of lymphocytes within the villous epithelium. The neoplastic cells are mostly small to intermediate-sized lymphocytes with a small nucleolus, 0 to 2 mitotic figures per 400x field, and scanty cytoplasm.

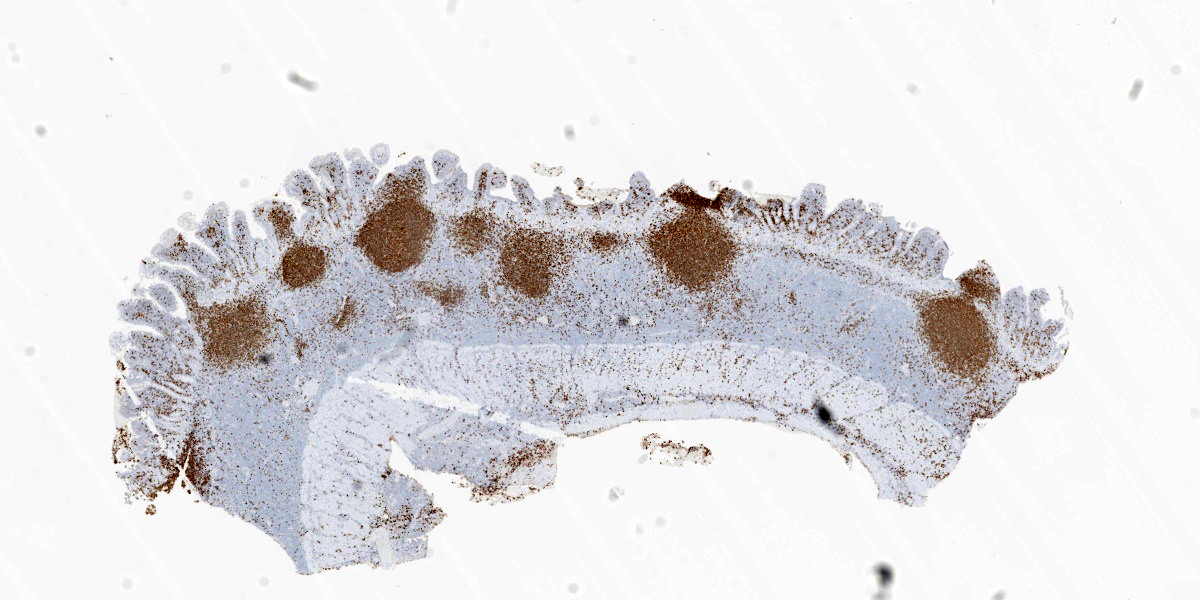

The following description is from slides that were not submitted: Similar neoplastic lymphocytes are found focally in the cecal mucosa and submucosa, but the epitheliotropism is not so obvious in the cecum, and submucosal lymphoid tissue has more organized follicles. The lymph node has only focal expansion of the paracortex by monomorphic small lymphocytes. Only a few sinusoidal clusters of neoplastic lymphocytes are in the liver. Otherwise, the liver has variable centrilobular congestion and degeneration that might account for the dark blotches noted at surgery. The sections of stomach are unremarkable.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Epitheliotropic T-cell lymphoma, jejunum.

Contributor’s Comment:

Despite the reportedly short duration of clinical signs, the histologic findings are typical of feline enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. This alimentary small cell lymphoma

can be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory bowel disease; indeed, there may be a continuum from chronic inflammation to lymphoma.2,3,6 However, in this case, the clusters and plaques of lymphocytes within the villous epithelium plus the extension into the submucosa and tunica muscularis left little doubt that this is a neoplasm of T lymphocytes.2,5 Therefore, neither PCR testing for antigen receptor gene rearrangement (PARR) clonality nor immunohistochemical (IHC) phenotyping with T-lymphocyte and B-lymphocyte markers was performed.

Alimentary lymphoma has become the most common form of feline lymphoma and seems to be increasing in prevalence. Most feline small intestinal lymphomas are composed of small cells and confined to the mucosa similar to the human WHO enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma type II.5,8 However, neoplastic lymphocytes extended through the submucosa into the tunica muscularis in this case, making it a transmural T-cell lymphoma (like WHO enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma type I). Small cell feline transmural T-cell lymphomas exist, but most are of large granular lymphocyte type.5 Importantly, transmural T-cell lymphomas have shorter median survival than that of mucosal T-cell lymphomas, but this could reflect the size of the neoplastic cells rather than the depth of invasion.5

Duodenal endoscopy is commonly used to assess cats with chronic enteropathy because it is a minimally invasive technique,1,6 but distinction of transmural lymphoma from mucosal lymphoma requires examination of full-thickness intestinal sections. A lymphoma diagnosed in endoscopic duodenal biopsy specimens would by default be classified as mucosal.5 In addition, because the jejunum is the most common location of feline intestinal lymphoma, the diagnosis could be missed in a duodenal specimen.1,5

The histologic distinction of lymphoma from inflammatory bowel disease, particularly in endoscopic specimens, is greatly facilitated by IHC and PARR.5,7 In fact, Sabattini et al. reported that for endoscopic duodenal specimens only the diagnosis of lymphoma based on clonality correlated with decreased survival.7 Nevertheless, clonality results can be mixed, leading authors of a literature review6 to propose that feline intestinal small cell lymphoma may more closely resemble human indolent digestive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease than enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. In a study of gastric or duodenal endoscopic biopsy specimens of clinically normal adult cats, histologic, IHC, and clonality test results were consistent with small cell lymphoma in 12 of 20 cats.3 Thus, the authors concluded that the standard criteria for diagnosing chronic enteropathy in cats may need modification.3

Contributing Institution:

Purdue University

Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory: http://www.addl.purdue.edu/

Department of Comparative Pathobiology: https://vet.purdue.edu/cpb/

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Lymphoma, intermediate to large cell, transmural.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was the one and only Dr. Bruce Williams who combined his twin loves of unusual pathology and cats to assemble a conference that featured a good amount of both aspects. The first case is a classic enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) which the contributor nicely describes and generated substantial discussion among conference participants (see below). We performed IHC for CD3, CD20, PAX5, and MUM1 which were diffusely reactive with strong cytomembranous immunoreactivity for CD3 (T-cell marker) in the cells of interest, confirming the diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma (figures 1-5, 1-6). We agree with the contributor that the extension of neoplastic lymphocytes through the submucosa into the tunica muscularis bests fits with an EATL type I interpretation. Interestingly, this case featured large lymphoid follicles that were strongly immunoreactive for CD20 and PAX5 (highlighting B cells) with fewer plasma cells (staining with MUM1) and B cells scattered within the lamina propria. We remarked on a similar finding in Conference 20, Case 4, 2014-2015 – this too probably represents a nexus of chronic intestinal inflammation that has transformed into lymphoma. However, the contribution of a leaky gut (and associated antigen pouring through an incomplete barrier) due to neoplastic lymphocytes disrupting and effacing the enteric mucosa should not be overlooked either in this case.

While the case seemed straightforward, conference participants pointed out several factors that could make this entity more difficult to describe definitively. Foremost, the size of the neoplastic lymphocytes was a point of contention, with some conference participants agreeing with the contributor’s description of small to intermediate size while others favored an intermediate to large distribution. Ultimately, the group felt that intermediate to large cells accurately reflected the neoplastic cells based on the more open chromatin pattern and large prominent nucleolus of these cells (‘centrocyte-like’). Dr. Williams entertained (and ultimately discarded) the possibility that these cells could reflect a large granular lymphoma (LGL) which is another high-grade large cell T-cell neoplasm, though this diagnosis is often better made on cytology which was not available for this case. Another confounder we considered were the normal population of small lymphocytes within the lamina propria – we focused on the submucosa first and later identified these same cells within the mucosa in making our determination. Participants were also focused on the intraepithelial nests and plaques of lymphocytes which is more classically associated with EATL type 2. There was also spirited discussion of the putative grade of this neoplasm as mitotic figures were rare (1 per 40x hpf) for some participants while others felt that the mitotic rate was at least intermediate (2 per 40x hpf). EATL type 1 tends to fit better with a more high-grade lymphoma which gave us pause. Ultimately, we resolved these points by focusing on the distinction between transmural and mucosal-associated lymphoma and leaving the EATL types aside which is a convention now shared by the ACVIM as discussed in the next section.4

Since the submission of case materials to the WSC several years ago, the ACVIM has published new guidance for distinguishing low?grade neoplastic (i.e. EATL type 2) from inflammatory lymphocytic chronic enteropathies in cats.4 Distinguishing these entities is challenging given the overlap in features. Clinical signs are largely identical for both conditions and current laboratory tests lack appropriate specificity and sensitivity to screen individual cats accurately, though they can help to pare down the differential list (e.g. rule out pancreatitis).4 Diagnostic imaging is a helpful adjunct for characterizing abnormalities of the intestine and adjacent lymph nodes as well as identifying appropriate regions for biopsy. Histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis, though the decision of endoscopic or laparoscopic biopsy, the number of samples to take, and the exact locations to sample remains an active area of discussion among clinicians.1,4 From a pathologist’s perspective, the ideal samples should be cut parallel to the lamina propria of the intestine, facilitating examination of the mucosa and any underlying tissue layers if present.1,4

Ancillary diagnostics tests help support the diagnosis of neoplastic or inflammatory enteropathy, but do not make the distinction in a vacuum. The use of IHCs such as CD3, CD20, PAX5, BLA36, CD79a, Granzyme B, CD56, Ki-67 and MAC387/IBA1 is helpful to confirm or refute H&E impressions.1 In this particular case, the monomorphic population of lymphocytes with transmural infiltration is highly suggestive of EATL on H&E alone before any antibodies are applied. In contrast, mild to moderate cases of lymphoplasmacytic enteritis also feature intraepithelial lymphocytes and increased numbers of lymphocytes within the lamina propria that are similar in appearance to plaques and nests found in emerging EATL.1 In many cases, the use of PARR could help resolve this debate, though for a subset of cases small biopsy samples with little DNA and/or patchy lesions with few T- and/or B-cells present could yield frustrating results.1 Therefore, clonality should never be considered in a vacuum. It's fair to say that if one enjoys the certainty or confident conclusions often found in WSC proceedings, reading feline intestinal biopsies probably isn’t the place to find it.

References:

- Freiche V, Paulin MV, Cordonnier N, et al. Histopathologic, phenotypic, and molecular criteria to discriminate low?grade intestinal T?cell lymphoma in cats from lymphoplasmacytic enteritis. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35(6):2673?2684

- Kiupel M, Smedly RC, Pfent C, Xie Y, Xue Y, Wise AG, DeVaul JM, Maes RK. Diagnostic algorithm to differentiate lymphoma from inflammation in feline small intestinal biopsy samples. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):212-222.

- Marsilio S, Ackermann MR, Lidbury JA, et al. Results of histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular clonality testing of small intestinal biopsy specimens from clinically healthy client-owned cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:551-558.

- Marsilio S, Marsilio S, Freiche V, Johnson E, Leo C, Langerak AW, Peters I, Ackermann MR. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines on diagnosing and distinguishing low-grade neoplastic from inflammatory lymphocytic chronic enteropathies in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2023 May-Jun;37(3):794-816.

- Moore PF, Rodriguez-Bertos A, Kass PH. Feline gastrointestinal lymphoma: mucosal architecture, immunophenotype, and molecular clonality. Vet Pathol. 2012;49(4):658-668.

- Paulin MV, Couronné L, Beguin J, et al. Feline low-grade alimentary lymphoma: an emerging entity and a potential animal model for human disease. BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:306-324.

- Sabattini S, Bottero E, Turba ME, et al. Differentiating feline inflammatory bowel disease from alimentary lymphoma in duodenal endoscopic biopsies. J Small Anim Pract.2016;57:396-401.

- Valli VEOT, Kiupel M, Bienzle D, Wood RD. Hematopoietic System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:230-232.