Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is the term for the human disease caused by N. fowleri. It is an acute, usually fatal, necrotizing, and hemorrhagic meningoencephalitis.9 Although CNS infections due to Acanthamoeba and Balamuthia have been recorded in animals, such as dogs, sheep, cattle, primates, and horses, there has been only 1 report of naturally acquired PAM in animals, namely in a South American tapir at a zoo in Arizona.1-3,7,8,10 Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis has been experimentally induced in mice, sheep, and monkeys.1,10 Naegleria fowleri is thermophilic and tolerates temperatures of up to 45° C; hence, the frequent association of PAM with a history of contact with naturally warm or artificially heated waters.1 The portal of entry is the olfactory mucosa. The parasite migrates to the brain via olfactory nerves. Incubation period is short, with onset of clinical signs several days following exposure. The disease rapidly progresses and usually culminates in death within 5-7 days.5

The life cycle of N. fowleri includes a trophozoite stage (amoebic form), a temporary flagellate stage, and, in unfavorable environments, a cyst stage. The cyst stage is susceptible to desiccation.9 Only the trophozoite stage of N. fowleri has been detected in CNS lesions. This is in contrast with other free-living opportunistic amoebae, where identification of cyst stages aids in their differentiation from Naegleria.5

Gross lesions vary and may or may not be present. Findings may include multifocal meningeal hemorrhages and tan-gray thickening of meninges, tan-gray deposits obscuring cerebellar cortical surface, and light brown and malacic brain parenchyma. Lesions may be bilateral and symmetrical.

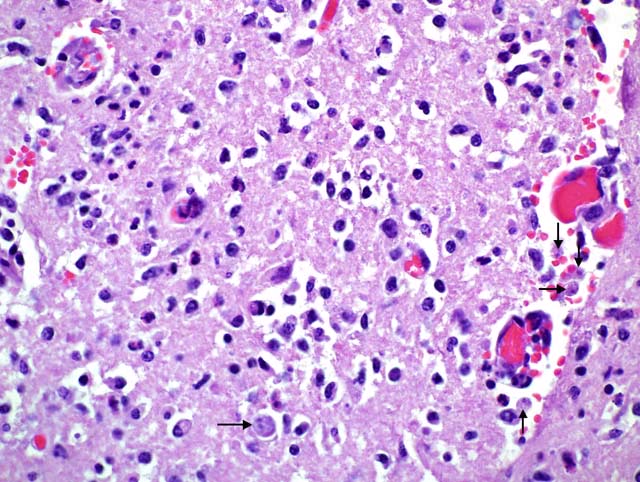

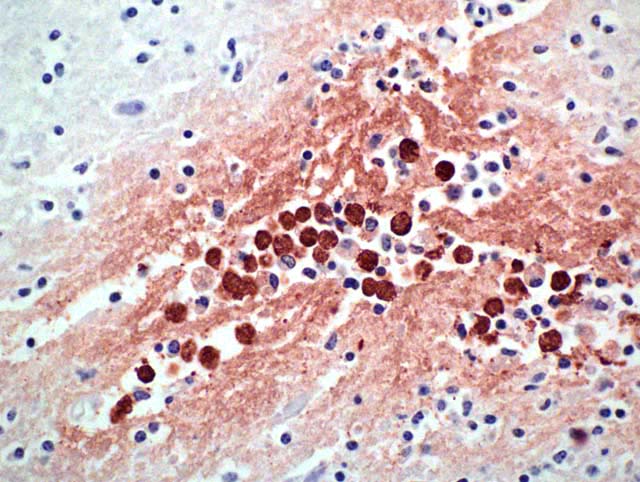

Histopathology shows mainly a multifocal, necrosuppurative, and hemorrhagic meningoencephalitis. Most severely affected areas were the anterior cerebra, olfactory bulbs, and cerebella. Amoebae are not easily detected microscopically because they resemble degenerate macrophages and may be few in number. The tendency of the amoebae to accumulate in aggregates or in perivascular spaces within areas of necrosis is most helpful, as is the small, weakly basophilic karyosome within a poorly delineated, small nucleus. There are very few or no multinucleated giant cells or eosinophils to direct the pathologist toward parasitic etiology. Some amoebae form cysts, visualized by periodic acid-Schiff stain, but N. fowleri does not, possibly because death occurs during the acute stage of the disease. Routine special stains to identify bacteria, such as Giemsa, Brown-Brenn-modified Gram, and Steiner silver stain were not helpful in identifying amoeba. Immunohistochemistry of the brain is an important tool in the confirmation of the diagnosis and also the isolation of the organism from animal tissues and suspected sources can be attempted. Finally, it is advantageous to know that the disease is seasonal, occurs in areas with high ambient summer temperatures, and may be associated with the use of consumption of untreated surface water.1

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Most animals infected with N. fowleri die before mounting a detectable adaptive immune response. The innate immune response, consisting of complement, neutrophils, and macrophages, appears to be a frequently inadequate defense mechanism. In vitro studies have shown that N. fowleri is able to evade complement damage by either expressing complement-regulatory proteins (CD59-like protein), shedding the MAC complex (C5b-C9) on surface membrane blebs, internalizing and degrading the MAC complex, or preventing the insertion of the MAC into the amoebic membrane.4 Although neutrophils play a major role in antiamoebic activity, their exact function is not clearly defined. TNF-_ does not have a direct effect on N. fowleri, but it appears that organism destruction by neutrophils cannot occur without TNF-_ being present.4 Production of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1_, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-_ do not appear to provide protection against infection.4 The roles of humoral and cell mediated immunity are also uncertain.

References:

2. Fuentealba, IC, Wikse SE, Read WK, Edwards JF, Visvesvara GS: Amebic meningoencephalitis in a sheep. J Am Vet Med Assoc 200:363-365, 1992

3. Kinde H, Visvesvara GS, Barr BC, Nordhausen RW, Chiu PHW: Amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Balamuthia mandrillaris (leptomyxid ameba) in a horse. J Vet Diag Invest 10:378-381, 1998

4. Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral GA: The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 51:243-259, 2007

5. Martinez JA, Visvesvara GS: Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol 7:583-598, 1997

6. Morales JA, Chaves AJ, Visvesvara GS, Dubey JP: Naegleria fowleri-associated encephalitis in a cow from Costa Rica. Vet Parasitol 139:221-223, 2006

7. Pearce JR, Powell HS, Chandler FW, Visvesvara GS: Amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Acanthamoeba castellani in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 187:951-952, 1985

8. Rideout BA, Gardiner CH, Stalis IH, Zuba JR, Hadfield T, Visvesvara GS: Fatal infections with Balamuthia mandrillaris (a free-living amoeba) in forillas and other old world primates. Vet Path 34:15-22, 1997

9. Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL: Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 50:1-26, 2007

10. Wong MM, Karr SL, Balamuth WB: Experimental infections with pathogenic free-living amebae in laboratory primate hosts: I. (B) A study on susceptibility to Acanthamoeba culbertsoni. J Parasitol 61:682-690, 1995